21 Tools of the Trade

By Mike Monnik, Arison Neo [1]

STUDENT OBJECTIVES

1) Why the Threat Intelligence matters for UAS

2) How to collect UAS Threat Intelligence

3) Using tools for historical and current Intelligence Collection

4) Using tools for current and future Intelligence Collection

Introduction

This chapter will observe several tools that can aid in the observation, prevention, and attribution of adversary use of drones. Identifying what tactics, techniques, and procedures an adversary might use can be useful in replicating their mindset. To replicate their mindset, it is important to catalog as many data points as possible of historical incidents or activities where the threat actor was involved. Intelligence-led is defined as applying criminal intelligence analysis as a rigorous decision-making tool to facilitate crime reduction and prevention through effective (policing) strategies. (Intelligence-Led Policing, 2020)

Drones are Cyber-Physical systems. This means that they operate via digital links, protocols, and on technology stacks that would represent that of a computer system. However, they are kinetic and can operate in physical space indoors, outdoors, near people, and at high altitudes near airplanes. As a result, tracking the malicious use of UAS requires a Cyber-Physical approach merging both traditional cybersecurity and threat intelligence aspects with Hostile Vehicle Mitigation (HVM). The era of mass tracking airplanes and even ships has grown rapidly over time, with websites like FlightRadar24 (flightradar24, 2022) and FleetMon (fleetmon – tracking the seven seas, 2022). However, these asset classes are expensive, rarely change callsigns (albeit due to regulation and international standards), and have identification technology to make this task more approachable. On the other hand, drones can be purchased for as little as USD 50 but could be positioned at the same altitude and geolocation as the planes mentioned above and ships. As of March 2022, there are currently 1000 drones in the air for every passenger aircraft, demonstrating the sheer volume and task of tracking and managing drones.

There are some attempts to standardize and legislate Remote Identification (RID) for drones to manage them, similar to vehicle license and registration. However, these technologies are still in their infancy. Clear distinguishing between International Friend or Foe (IFF) is still very difficult. As observed in the Ukraine-Russia conflict, it can be hard to compare a drone in the air to friendly forces, a journalist, a civilian, or an adversary. As a result, tracking all drones is not yet possible – most commercial drone detection or counter-drone (C-UAS) systems provide hyperlocal (2-10 km range) tracking capabilities, with military systems more than 100km, but usually with a focus on those with larger cross-body sections. However, it is important to track malicious drone incidents, the threat actors behind them, and the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) they employ. By tracking specific scenarios, the equipment used, and the data behind them, a team can create mock scenarios to test the effectiveness of C-UAS against realistic incidents and flight profiles.

There are three main varieties of Test & Evaluation practices for assessing the effectiveness of a drone mitigation system. The first is a Table-Top exercise, otherwise referred to as a “War Room,” which brings all relevant stakeholders into a room to theorize an incident, practice their response and evaluate lessons learned. This is a largely theoretical activity but has the ability for anyone to participate, including management, legal, security, marketing, and more. The key outcome of a tabletop exercise is to identify key roles and responsibilities, playbooks for following during an incident, and gaps that can be improved upon in communication. These exercises are best suited to organizations that have started thinking about protecting their assets. They might want to evaluate the best defense mechanism, whether people, processes, or technology (e.g., Counter-UAS).

An Aerial Threat Simulation focuses on the practical, pitting a mock adversary “Red Team or OPFOR” against the defense “Blue Team or BLUFOR.” In these exercises, usually at a live deployment or test facility, both teams know and agree on various scenarios, equipment, and flight profiles. These are then executed against the system involved, and its response is studied carefully in each category – such as Detect, Identify, Track, Mitigate and Recover. There are no surprises, but the objective is to evaluate if the system does what it says on the box and the extent of the variance. These exercises are best suited to organizations that have completed a Table-Top exercise and are looking to validate a vendor’s claims or refine their Blue Team doctrine.

A Red Team exercise is kept confidential to upper management only, and the BLUFOR team is not informed that a test might occur, how, or when. This is the upper echelon of C-UAS Test & Evaluation and focuses on the end-to-end solution and the team’s capability to detect and mitigate unknown, unexpected threats. The Red team uses various equipment, including fixed-wing, quadcopters, and multi-copters of varying make, model, color, size, and speed. Various flight profiles are also used, including fast, slow, First-Person View (FPV), Beyond-Visual-Line-of-Sight (BVLOS), One-to-Many (swarms), and by direction (such as the nape of the earth, directly above, zigzag, and extremely high altitudes). A variety of ranges might include launching extremely close or very far from the target perimeter. The Red Team may employ a variety of payloads, such as delivered by payload dropping mechanisms, kamikaze (loitering munitions) where the drone ferries the payload into the target, or remote trigger Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs).

Obfuscation and anti-attribution techniques such as automated and semi-automated flights, GPS or RF ‘dark’ systems, and protocols such as GSM or custom Software Defined Radio (SDR) frequencies may be used. In some cases, the Red Team also does not know what capability the BLUEFOR team possesses, which allows them creativity and realism in selecting their equipment and attack techniques. The objective of the exercise is to mimic a real-world threat actor by budget, technology closely, and technique, catching the BLUEFOR team by surprise and effectively evaluating their (and the technology’s) response. These exercises are best suited to organizations that have completed multiple Tabletop exercises and Aerial Threat Simulations and want assurance on their defensive playbook, people, technology, communication, and reaction.

By gathering UAS threat intelligence data of known incidents, threat actors, and their TTPs, we can design comprehensive and accurate scenarios for use within the Test mentioned above & Evaluation activities. The collection of UAS incident data should be categorized by type, equipment, and geolocation so that the Red Team’s actions or relevant. There is little benefit in testing a narcotics payload delivery against a critical infrastructure asset that faces explosive or surveillance threats. Most drone threat actors can be differentiated between the clueless, the careless, the criminal, and the terrorist. Most incidents can be categorized into the following: Intrusion (Trespass, ISR), Aviation (Near-miss, Sighting), Collision (Building, vehicle, asset), Contraband (Narcotics, Equipment, Arms), Weaponization (payload, IED, loitering munition), or Mitigation (jamming, spoofing, counter-UAS). The drone may be a fixed-wing system, quadcopter, or multicopter, of different make and models.

Most counter-UAS vendors, and many pro-active security teams today, have a UAS threat intelligence partner or organization which captures, analyses, and disseminates intelligence to them, replacing the need for, and skilling up, a dedicated human resource. This information can be separated into three key categories – alerts, analysis, and information. Alerts are actionable, time-critical alerts that may trigger a response by the receiver, usually calculated by the analyst as being high impact or priority. The analysis is an in-depth assessment of an event, threat actor, or technology that can provide useful insights to inform product development lifecycles or Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). Information about where incidents are occurring and how often can be further extrapolated to understand important information such as threats in geographic regions, frequency, and enough data, to be used by AI/ML to identify and mitigate threats automatically.

Before data extraction can take place, it’s important to remember these key aspects of information processing:

Accuracy:

- Is there other intelligence or sources to support the event?

Reliability:

- How credible (or historically reputable) is the source?

Timeliness:

- When was this observed? Is it new, or does it include old/stock media?

In some cases, a random tweet by a civilian on Twitter may not be able to be corroborated – yet might contain timely and important information regarding an emerging threat. In this case, the information could be reported as “unvetted” – giving the relevant customers awareness but a caveat that the information may not be true or entirely complete. This is especially important in times where a flurry of social media posts might indicate an occurring terrorist attack before other sources have been able to confirm

Tools for UAS Threat Intelligence

Any intelligence analyst tasked with gathering UAS threat and incident data will eventually need to automate, aggregate, triage, analyze and then disseminate the produced information. This section introduces both free and paid, open and closed-source tools that can do this. Intelligence can be strategic or tactical, ranging in type and frequency. These include monthly trends, weekly briefs, daily ‘presidential’ style updates, or common operating pictures (COP) filtered by region, equipment type, threat actor, or incident kind. Different customers will require unique intelligence use-cases depending on their environment and risk appetite.

For example:

- Airports might require detection of all drones within a 10km radius of the airport

- Prisons might require threat actor TTPs and incidents occurring within their country

- Ports might require online chatter or sentiment regarding pirates using drones to disrupt shipping

Lastly, intelligence with enough identification of trends, patterns, and attributes of threat actors can be used to highlight the vulnerabilities that could be used to exploit and mitigate them.

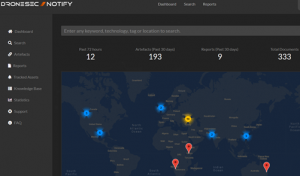

Figure 21.1 A typical UAS Threat COP over one month.

Source: DroneSec (DRONESEC, 2022)

Open-Source Tools

Open-source tools collect data from the internet that does not require authorization to access. These can be both free and paid. Examples include:

- Aviation Authorities

- AIRPROX

- Law Enforcement

- Ministry of Defense

- Social Media (Twitter (twitter, 2022), Facebook(Facebook , 2022), Instagram (Instagram, 2022), TikTok (tiktok, 2022), Snapchat)

- Open Chat Groups (Telegram (telegram, 2022), Discord (Discord, 2022), Slack (Slack, 2022))

- Internet forums

- News

- Media (YouTube (youtube, 2022), LiveLeak (Wikipedia, 2022))

- Livestreams

- Search Engines (surface and open TOR (torproject, 2022)/Dark Web (whats-the-dark-web-how-to-access-it-in-3-easy-steps, 2022))

- Threat Intelligence feeds (DroneSec, (DRONESEC, 2022) LiveUAMap (liveuamap, 2022))

Closed-Source Tools

Closed source tools often require payment to access but can draw on open-source information. The medium itself may be a closed source, requiring authorization.

- Counter-UAS detection feeds

- Closed Social Media groups, Chat groups (Signal (signal.org, 2022)), and Forums

- Closed TOR/Dark Web sources

- Curated Threat Intelligence feeds (e.g., DroneSec (DRONESEC NOTIFY, 2022), Dataminr (Dataminr, 2022))

- Journalists, Word-of-Mouth

Collection data types

When collecting information about a drone incident, it is important to log the event’s context or metadata.

Common but important data points for collection include:

Table 21.1 Important Data Points for Collection

| Type | Example |

| Geographic Location (General, Exact Coordinates) | Melbourne, Australia (-37.7837, 144.9618) |

| Date, and Time (UTC) | 31/03/2022 14:37:21 |

| Make, Model, Sub-Model | DJI Mavic 3 Professional |

| Location Category | Mass Assembly |

| Activity Category | Intrusion |

| Activity Result | Sporting game paused for 20 minutes |

| Seizure of the drone | No |

| Apprehension of the operator | No |

| Visuals | Yes (pictures, videos) |

| Payload | Ukrainian Flag attached by string to landing gear |

| Size | sUAS |

| Color | Painted sky blue |

| Serial Number | Unknown |

| Other system components (e.g., controllers) | Unknown |

| Known hardware mods | Appeared to have extended battery pack known known known |

| Known software mods | Unknown |

| Threat Actor Group | Local activists |

| Detection type | Civilian visual observation, social media (links) |

| C-UAS Detection | No |

| C-UAS Mitigation | No |

Source: DroneSec (DRONESEC, 2022)

By collecting as much data as possible, post-event forensics can be performed and cross-referenced with other detection systems, CCTV, visual observations, or law enforcement records are possible. Further activities include using AI/ML to learn from these datasets to perform on-the-fly risk-based decision modeling and prediction capabilities.

By gathering this unique data, trends and patterns can emerge, and data-drive questions can be answered, such as the following examples:

- Are we seeing an increase in narcotics-style incidents within the country of Ethiopia?

- Are C-UAS implementations or new legislation working, given our data on seizures or apprehension?

- Is the increase in DJI Mavic 3 drones in Afghanistan due to a supply chain from Israel?

- What is the most dangerous or most expected UAS threat right now?

Tools for historical and current UAS threat intelligence

Configuring Google (Open-Source, free)

However, search engines are a powerful tool for locating data regarding drone incidents and can provide a significant signal-to-noise ratio. The analyst must have a specific direction in their collection to focus on key filters, such as sources, timelines, or information types. For example, the query “drone incident” may produce thousands of results; however, filtering it to items in the last seven days or appending a specific country will provide significantly more valuable and relevant results. It is highly recommended that users study “Google Dorks” (Google Dorks Primer, 2022) to make the best use of the search engine’s advanced search and filter capabilities.

To refine the query “drone incident” in Google to the past 24 hours:

- Click on the “Tools” tab

- Click on “Past 24 hours.”

Figure 21.2 Using search engines to list incident events in the past seven days.

Source: DroneSec (DRONESEC, 2022)

This process can be repeated in an automated fashion with the word “drone” being replaced by “UAS,” “UAV,” “RPAS,” “quadcopter,” “multirotor,” or even “fixed-wing.” Keep in mind that each country has nuances regarding the way they designate drones – for example, in the USA, a small drone might be referenced by “UAS” and “C-UAS,” In contrast, in Australia, the terminology is often “RPAS” and “C-RPAS,” respectively.

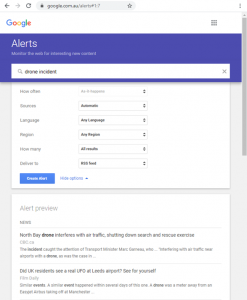

Alternatively, users can set up ‘keyword alerts’ in Google to receive alerts via email or RSS. This can be done via the web URL https://www.google.com.au/alerts. Users may want to stack their queries, such as having the keywords: drone incident, drone collision, drone terrorist, drone airport. (google.com.au/alerts, 2022)

This methodology can be applied to most search engines with various customization options available.

Figure 21.3 Google.com au/ alerts

Source: (google.com.au/alerts, 2022)

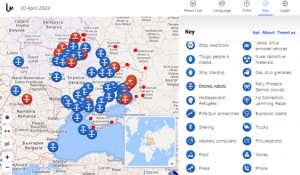

Configuring LiveUAMap (Open-Source, paid)

Live Universal Awareness Map (LiveUAMap) is a global news and information site related to factual reporting of incidents and events. The system covers various categories, not just aerial drones – but can be filtered to demonstrate just drone threats. The system has a free version but is limited in what it can show. The system generally retrieves tweets from Twitter, often the fastest reporting source for events occurring in real-time around the world. (liveuamap, 2022) Analysts should always use multiple tools for incident collection, to cross-reference and verify reports and increase their list of sources – LiveUAMap only covers twitter but does so very well.

To configure LiveUAMap for a COP view:

- Select the geographic region “world” or navigate to https://world.liveuamap.com/

- Select the tab “Time” and highlight the specified time/date

- Select the tab “Key” and select the category “drones, robots,” and press Apply

Figure 21.4 A global view of tweeted drone incidents

Source: LiveUAMap (liveuamap, 2022)

Tools for current and future UAS threat intelligence

To gather intelligence that might pertain to future incidents and malicious use of UAS, analysts need to gather data that might be best represented in the discussion or planning of an event in the future. While social media can support this, authorization or invitation is often required to join underground or closed groups that share detailed information. Payment is required for advanced UAS Threat Intelligence gathering platforms as their operatives or technology actively participate in and, as a result, gather information relating to potential malicious use of UAS. This section will cover free and paid mechanisms for gaining closed-source information to support UAS threat intelligence collection.

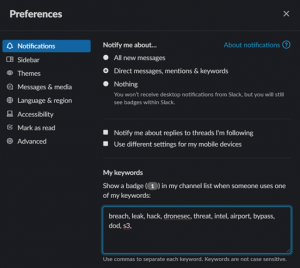

Configuring Slack (Closed-Source, free)

Slack can be configured with silent keyword alerts so that any time the word is mentioned, you receive a notification. This can be useful for groups that actively plan malicious UAS use for predicting future events. Slack is a closed-source tool as you are required to join that group to monitor it, of which others can observe your presence. It is highly recommended to use incognito sock-puppet accounts when joining any source that requires authorization.

- Go to Profile -> Preferences -> Notifications

- Change to “Direct messages, mentions & keywords.”

- Paste a word list into the “My keywords” section

Figure 21.5 A collection of words for slack.

Source: DroneSec (DRONESEC, 2022)

Your wordlist is a collection of terms that match what you might be looking for. These can be hundreds or thousands of keywords in volume and use Natural Language Processing (NLP) for other language translations in advanced intelligence-gathering operations.

This will notify you (or a selected webhook) when your keyword matches any public message in any channel. Similar yet alternative options are available for Discord, Skype, Telegram, and Signal.

DroneSec Notify (Open/Closed-Source, free/paid)

DroneSec is the premier UAS security incident tracking organization globally. DroneSec has other capabilities in drone security and counter-drone training (training – dronesec, 2022), tooling and intelligence that support Law Enforcement, Military, Government, and Private Industry, and runs the largest drone security conference (Global Drone Security Network) in the world. The DroneSec Notify UAS Threat Intelligence Platform (TIP) automatically crawls the internet (open and closed sources) and reports on UAS incidents. Rather than a static physical detection system, the platform acts as a COP, providing data fusion between hundreds of open and closed sources. The organization produces both a free weekly intelligence brief (dronesec-notify (pages), 2022) and a paid subscription (dronesec-notify (pages), 2022), which provides 24/7 real-time threat alerts, notifications, and a database.

The Notify system is highlighted in this chapter as it is the only dedicated Threat Intelligence Platform designed for UAS threat and incident collection, analysis, and dissemination. It was developed (Neo, 2022) for analysts, security teams, and counter-drone systems to monitor, share and report events on a global scale. The system includes the following functions:

- – Dashboard COP for a collection of recent incidents, visual map, and visual statistics

- – Search for querying the database of over 4000+ drone incidents by various filters and categories

- – Artefacts for viewing Medium and Low priority drone incidents and events

- – Reports for viewing High priority incidents and contextual analysis

- – Tracked Assets for setting up alerts and notifications when a query match is found

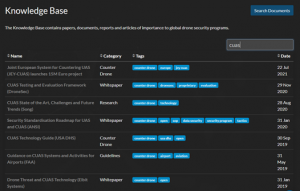

- – Knowledge Base for a collection of tailored Reports, Whitepapers, Guidelines, and Research on the topics of drone security, counter-drone, drone cybersecurity, regulations, and more

- – Statistics for viewing the number of artifacts over time, by various categories, trends, and types

Interpreting the free weekly summary includes the following incident categories:

- Non-conflict-zone

- Conflict-zone

- Cyber and data security

- Social media

- Whitepapers, Publications, and Regulations

- Counter-Drone Systems

- UTM Systems

- Informational

- Technology

Figure 21.6 The free, weekly UAS Threat Intelligence brief Source

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

This provides a holistic view of physical and cyber threats, incident actors, mitigations, and threats to swarms and connected nodes.

The system provides:

- Monitoring and tracking keywords, geographic locations, trends, statistics, and curated analysis

- Access to intelligence on cyber vulnerabilities, exploits, and modeling tools

- Access to a detailed UAS Threat Actor Glossary, including tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs)

Figure 21.7 The UAS TIP provides global incident tracking and analysis capabilities.

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

To configure Notify, users access the dashboard, where they are presented with a global view of incidents in the past two weeks. Multiple incidents occurring within close proximity to each other are grouped and can be individually viewed. Additional filters include events occurring in the past 72 hours, artifacts and high-priority reports over the past 30 days, and documents within the knowledge base.

Figure 21.8 The DroneSec Notify UAS TIP Dashboard

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

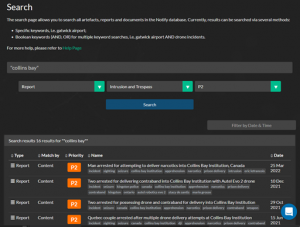

Searching the database is easy and based on keywords. These keywords can be exact, inclusive of, or supporting Boolean operations such as the use of “AND,” “OR” operators for refining results. Users can also click and include tags that provide thousands of possibilities based on country, make, model, incident type, payload, or even specific threat actors.

Figure 21.9 Performing a search for a specific prison Source

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

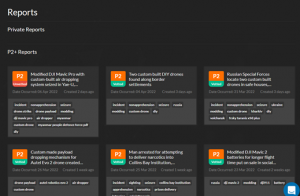

Reports are curated incidents that are critical-to-high priority items that will most likely trigger an alert or constitute in-depth analysis by UAS Threat Intelligence Analysts. These reports can range from P1 (Critical) to P2 (High) and usually result in a successful contraband drop, violence or death caused by a payload, or significant events such as aviation near-misses and airport intrusions. The Reports page provides a user with a running list of the most recent and important UAS events globally.

Figure 21.10 Viewing a running list of recent high-priority reports.

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

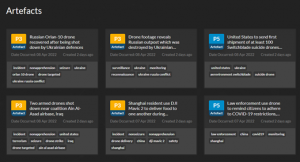

Artifacts are medium-to-informational priority items that do not constitute an alert (unless set up for tracking) nor in-depth analysis by UAS Threat Intelligence experts. However, they can be important to the right user, and their frequency and type dictate the level of malicious UAS activity within the world. These artifacts can range from P3 (Medium), P4 (Low), to P5 (Informational).

Figure 21.11 Viewing a running list of UAS artifacts

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

The platform also contains a Knowledge Base, a central repository for all drone physical, cyber, and countermeasure security documentation. The space was intended to be a data lake for SOPs, frameworks, guidelines, and research relating to the area. This allows teams to speed up their creation of a drone security program, red team, or conduct comprehensive literature reviews in a central place. The Knowledge Base also includes all DroneSec-generated content, such as Special Reports, cybersecurity databases, and counter-drone test & evaluation frameworks.

Figure 21.12 A search for C-UAS related content in the Knowledge Base

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

Finally, the system contains a documented UAS Threat Actor Glossary, centralizing all known threat information about the group and its technology, tactics, techniques, and procedures. It also links users to previous events attributed to the group and potential future capabilities. Lastly, the statistics page is useful for analysts to understand the trends involved in drone incidents from a number’s perspective, giving them insight into resource allocation and potential predictions of future UAS misuse. DroneSec Notify is an important tool in any analyst, first responder, or Law Enforcement Agent’s kit for staying at the bleeding edge of malicious use of UAS by threat actors.

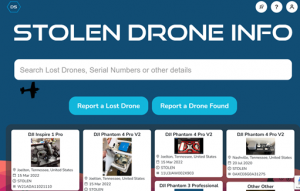

Stolen Drone Info (Open/Closed-Source, free/paid)

Intelligence demonstrates that a large percentage of the drones used by criminals for crimes such as dropping contraband into prisons or across borders are stolen. Drone operators and retailers have reported their homes, cars, and shops being burglarized with their drones stolen; these drones are usually resold on the black market, used for illegal payload delivery drops, or even contribute to the procurement and supply of drones to terrorist entities. The primary reason crime groups seek to use stolen drones is to mask their identity to reduce the risk of capture. (Crime Facts Info, 2022) This is because the original drone operator’s identity is linked to the system given a variety of attributional factors:

- – The original operator’s financial information was linked to the purchase

- – Store accounts, CCTV, or receipt tracking may link to the operator

- – The operator’s drone account was linked to the drone, controller, or device

- – The operator had registered the drone’s serial number with the manufacturer or aviation authority

- – The operator’s digital media and/or GPS telemetry may still exist within the drone’s storage

Stolen Drone Info is an online database that can be used by drone operators, drone detection systems, agencies, and organizations to report and detect drones that have been stolen. The tool can aid in tracking drones, connecting users back to their merchandise, and keeping the skies safe from stolen ones. Additionally, the tool decodes serial numbers, letting users know if the drone they are purchasing is legitimate or stolen. Being an automated system, the tool can crawl open-source locations to determine if entries match the database of stolen systems up for sale. If already sold or used by malicious individuals, a network of drone detection nodes can match entries in the database with drones in the air.

Figure 21.13 The Stolen Drone Info tool dashboard

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

Open-source data can be trawled from the internet and social media such as Facebook and Craigslist, where marketplace and chat forums exist. Serial numbers are usually mentioned in these places, and users try to engage the mass media to search for the owner of the drone found or in hopes that someone would have found their lost or stolen drone. These avenues usually result in low success rates as the finder and the seeker may not be in the same forums, chat rooms, or marketplaces. With a consolidated registry that combines these avenues and links, everyone increases the chances of matching the drone to its rightful owner.

Connecting drone detection systems and law enforcement agencies are critical in providing real-time threat intelligence and enhancing decision-making abilities. Drone detection systems can detect drones operating in an area and automatically retrieve their data, including make, model, serial number, and location. In some systems, the operator’s location can be detected as well. This data can be automatically mapped to the registry’s database and alert the relevant authorities when a stolen drone’s serial number appears in the detection system. Additionally, counter-drone systems often perform several decisions based on data available to them to ascertain if the drone is malicious or not. The drone is stolen at the point of detection tolen provides a more confident data source for the counter-drone operator’s decision tree.

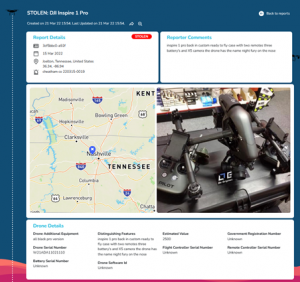

Figure 21.14 Example of a stolen drone reported on the SDI

Source: (DRONESEC, 2022)

The tool significantly increases the chances of stolen drones being located and reduces opportunities for the drone to be sold to unsuspecting purchasers or used for malicious crimes under the original owner’s identity. Law enforcement and federal agencies can access the database to improve seizure and apprehension rates, protect civilians and reduce the influx of crimes using drones.

The reports include critical information such as the drone’s make and model, serial number(s), distinguishing features or accessories, registration number, and location. The most important information, the serial number, is unique and present for all drones, distinguishing one from another. The same number is read by detection systems (or physically) by the drones transmitting links. Certain brands’ serial numbers have data embedded within the drone’s manufacture date, make, and model that can be decoded easily. In contrast, others may only have the batch number or location of assembly and distribution. This information may be important in determining the origins of the drone, such as where it was purchased from and possibly linking out the supply chain to the drone operator or threat actor. Other information such as distinctive features or accessories helps differentiate one similar model from another, which adds to the identifiability of the drone.

The Stolen Drone Info tool is a useful component in reducing the anonymity of threat actors using stolen drones and increasing the chances of detecting such drones by detection systems. It can aid analysts in observing geographic hot spots, specific make and models of drones, and even reunite drones with their original owners.

Conclusions

To be aware of potential threats and understanding the threat is required. This can be extracted from strategic and tactical Threat Intelligence using various tools discussed in this chapter. The theory of unmanned system tracking is still early, and its application will continue to apply to the underwater, surface-based, ground, and even satellite-based systems. Cyber-physical systems have close linkages to both cybersecurity and physical security intelligence operations. Data fusion is a requirement to provide an accurate, timely operating picture of the threats posed and how to counter them. Historical context can aid the creation of trends and patterns that can be observed for unique items, leading to future predictions and safer skies.

Bibliography

Crime Facts Info. (2022, 03 01). Retrieved from Australian Institute of Criminology: https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/cfi055.pdf

Dataminr. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.dataminr.com: https://www.dataminr.com/

Discord. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from discord.com: https://discord.com/

DRONESEC. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from dronesec.com: https://dronesec.com/

DRONESEC NOTIFY. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from dronesec.com/pages/notify: https://dronesec.com/pages/notify

dronesec-notify (pages). (2022, April 10). Retrieved from dronesec.com/pages/dronesec-notify : https://dronesec.com/pages/dronesec-notify

Facebook . (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.facebook.com: https://www.facebook.com/

FleetMon – tracking the seven seas. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.fleetmon.com: https://www.fleetmon.com/

flightradar24. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.flightradar24.com: https://www.flightradar24.com/

Google Dorks Primer. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.secjuice.com/osint-engagement-101: https://www.secjuice.com/osint-engagement-101/ Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cz2bgvEzbuo

google.com.au/alerts. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.google.com.au/alerts: https://www.google.com.au/alerts

Instagram. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.instagram.com: https://www.instagram.com/

Intelligence-Led Policing. (2020, May). Retrieved from https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/cfi055.pdf: https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/cfi055.pdf

liveuamap. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from liveuamap.com: https://liveuamap.com/

Neo, A. (2022, April 10). why-we-created-threat-intelligence-platform-drones. Retrieved from www.linkedin.com/pulse: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-we-created-threat-intelligence-platform-drones-arison-neo/

signal.org. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from signal.org: https://signal.org/

Slack. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from slack.com: https://slack.com/

snapchat. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.snapchat.com: https://www.snapchat.com/

telegram. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from telegram.org: https://telegram.org/

TikTok. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.tiktok.com: https://www.tiktok.com/

torproject. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.torproject.org: https://www.torproject.org/

training – dronesec. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from training.dronesec.com: https://training.dronesec.com/

twitter. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from twitter.com: https://twitter.com/

whats-the-dark-web-how-to-access-it-in-3-easy-steps. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.vpnmentor.com: https://www.vpnmentor.com/popular/whats-the-dark-web-how-to-access-it-in-3-easy-steps/?keyword=dark%20web&geo=95821&device=&cq_src=google_ads&cq_cmp=367844759&cq_term=dark%20web&cq_plac=&cq_net=s&cq_plt=gp&keyword=dark%20web&campaignID=367844759&matchtype

Wikipedia. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LiveLeak: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LiveLeak

Youtube. (2022, April 10). Retrieved from www.youtube.com: https://www.youtube.com/

[1] DRONESEC© is the copyrighted name for the Australian – based company. Reference to its product line and company name is both authorized by the company and requested by the authors as representative of the best of breed tools of the trade. In the Managing Editors’ opinion, DRONESEC© represents one of the strongest drone monitoring services in the world. However, officially the authors under the current CC, KSU policies, and publisher – New Prairie Press, are not permitted to endorse any product by any company.