Chapter 12: C-UAS Regulation, Legislation, & Litigation from a Global Perspective

W.D. Lonstein

Student Learning Objectives

Counter Unmanned Aircraft Systems ("C-UAS") have opened the latest example of the dynamic interface between technology and law. It is the strong suggestion of the author that students access Unmanned Aircraft Systems in the Cyber Domain, as a launch point for this chapter. Many of the fundamental principles and considerations discussed concerning law and UAS will serve as a primer to this chapter's discussion of Counter UAS regulation and jurisprudence. (Nichols, et al., 2019) With the rapid development and implementation of automation and artificial intelligence ("AI"), including Unmanned Aircraft Systems ("UAS"), legal systems globally will be forced to balance public safety with the many benefits to everyday life. Legal scholars and legislators have wrestled with the friction between technology and law centuries. Students will be exposed to historical, examples of the techno-legal balance and asked to consider how best to as apply general principles to the challenges posed by C-UAS technology and its implementation globally.

Once Completed Students Should:

Have a broad perspective on the global variances and gaps within C-UAS law globally.

- Consider the impact of the ability to operate UAS remotely and the possibility C-UAS activity may cause legal ramifications beyond the jurisdiction where it occurs.

- Examine whether a particular C-UAS technology such as Kinetic, non-kinetic, passive, active, laser, acoustic, jamming, and spoofing, might be subject to direct or indirect, regulation, and possible liability.

- Consider the sufficiency of the current statutory framework and jurisprudential precedent as it pertains to C-UAS design, deployment, or operation.

- Appreciate the likelihood of conflicting civilian and military C-UAS regulations impacting a particular deployment, technology, or location.

Current C-UAS Regulatory Landscape

The current state of C-UAS jurisprudence is in its infancy with widely divergent regulatory landscapes around the globe. From a general perspective, most nations prohibit an individual or private company's right to a "self-help" C-UAS policy (i.e., the prohibition of shooting down a drone at all with kinetic or non-kinetic measures). Much the same as is the case within the United States, internationally, private C-UAS activity is strictly prohibited unless conducted under the auspices of the military or police function. Students might ask why there is no right for a person (s) to protect their physical safety, property, pets, farm animals, and privacy from the threats posed by unwanted drones. The answer, though less than satisfactory to many, is that there may be many unintended consequences from self-help C-UAS activity. What if police were seeking a poacher of animals in the forest next to the farm? Now the facts implicate damage to police property, interferes with legal police activity, not to mention creates risks to others caused by the crash of the drone once disabled.

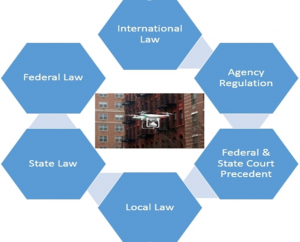

At first glance, it might seem that such a policy runs contrary to individual and property rights (Figure 12-1), especially if the drone is flown over private property or otherwise being flown dangerously or recklessly in public the prohibitions are grounded in logic.

Figure 12-1 Angry Farmer Spoof

Source: (Junkin Media , 2016)

A global survey of current C-UAS regulations reveals near uniformity in most nations, prohibiting any C-UAS activity taken by any entity other than the National Security Apparatus, Civil Aviation Authorities, and military. Most notably and understandably, "self-help" C-UAS, such as that depicted in Figure 12-1, may seem a simple and understandable reaction to an apparent privacy invasion or aerial trespass. The challenge for C-UAS practitioners is when dealing with perceived threats from an aerial trespasser, shooting it out of the sky can have serious consequences.

Let's assume the farmer in Figure 12-1 is actually in Scranton, Pennsylvania, instead of the United Kingdom. What are the ramifications of a landowner, seeing a drone fly over his land at low altitude, deciding to use a shotgun to shoot it out of the sky? Applying current C-UAS law to this scenario reveals a confusing and uncertain landscape for confronting what is sure to become a more common occurrence Figure 12-3 traces the growing spectrum of Federal C-UAS regulation in the United States.[1] In addition to federal laws that prohibit "self-help" C-UAS activity, international laws, state laws, agency regulations, rules, and precedential court decisions can subject the farmer to significant criminal or civil consequences. Depending on the action

taken, and for our purposes, we will use the farmer with the shotgun that may result in criminal or civil liability under a complex interaction of various federal, state, and local laws.

Figure 12-2 Global C-UAS Legal Implication Matrix

Source: (West, 2019)

Back to our farmer, not only is he subject criminal liability under an array of federal laws and regulations, but he may have also run afoul of numerous state, local laws as well as subject himself to civil liability. A civil action is one brought by an injured or aggrieved party for monetary damages against the party who allegedly caused the loss. In the case of the farmer, a lawsuit might be filed by an injured party, including the drone owner, the drone operator, and even the person who may have hired the operator to perform a specific mission or task.

When the force of gravity added to the scenario, the situation gains complexity. According to Michael Hamann, there are many risks attendant to these kinetic countermeasures. The payload, if harmful, may well be dispersed throughout the crash area as well the impact of a plastic rotary falling from the sky has caused a crash test dummy to receive a powerful effect ranging from 9 foot-pounds and 233 foot-pounds, depending on the angle and speed of the falling drone. (Michael Hamann, 2018), citing (FAA UAS Center of Excellence, 2017)

To further complicate things, if the farmer successfully shot down the drone, and it landed on the head of his neighbor who succumbed to the injuries, he sustained an additional set of legal consequences will unfold. For example, the heirs of the deceased neighbors might seek to bring claims for civil damages, including but not limited to wrongful death and negligence. Criminal charges may result from the illegal shooting and the killing of the neighbor. Tables 12-3 – 12-5, below demonstrate the complexity of implications from the United States, as well as other nations, relating to C-UAS activity.

TABLE 12-1: UNITED STATES FEDERAL LAW

| Federal Law or Regulation | Countermeasure | Prohibition or Rule | Penalty |

| FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 | N/A | Limits C-UAS authority to DHS, DOJ & U.S. Coast Guard and requires consultation with Department of Defense | N/A |

| Title 47 U.S.C. § 301 et., Seq. | Radio Interference

Signal Disruption |

47 U.S.C. § 301

Radio Transmitter License Required

47 U.S.C. § 302 Illegal to own sell, import, or operate radio signal “jamming” technology.

47 U.S.C. § 320 Allows FCC to require any radio station which in its opinion may interfere with distress signal of ships be required to have a licensed operator listening for distress signals.

47 U.S.C. § 325 Prohibits False, fraudulent or unauthorized distress or other re-broadcast of radio signals.

47 U.S.C. § 333 Prohibits willful or malicious interference with radio communications.

47 U.S.C. § 605 Unlawful interception of radio transmission

|

47 U.S. Code § 502 not more than $500 for each and every day during which such offense occurs

|

| 18 U.S.C. Chapter 119

Interference with government & satellite communications |

Jamming, Spoofing & similar countermeasures | 18 U.S.C. § 1362

Interface with Government Communications

18 U.S.C. § 1367 Interference with Satellite Communications

|

Fines and imprisonment of not more than 10 years |

| 18 U.S.C. § 32

Destruction of Aircraft or Facilities |

Destruction of aircraft - | Fines and/or imprisonment of not more than 20 years. | |

| 18 USC § 2510, 2511

Wiretap Act

|

“Spoofing" a GPS or other controlling signal or communication. | 18 U.S.C. § 2511

Interception of Wire Communications

|

Fines up $ 250,000 and imprisonment of not more than 10 years |

Source: (Federal Aviation Administration, 2018)

TABLE 12-2: STATE LAWS IN CALIFORNIA & NEW YORK

| State Law or Regulation | Countermeasure | Prohibition or Rule | Penalty |

| New York Penal Law | Shooting Drone with Shotgun | NY Penal Law § 145.05: Criminal Mischief in the Second Degree:

Intentionally damage someone else’s property in an amount that exceeds $ 1,500.00

NY Penal Law § 145.05: Criminal Mischief in the Second Degree:

Intentionally damage someone else’s property in an amount between $ 250.00 and $ 1,500.00

NY Penal Law § 265.35 (2) Unlawfully discharging a firearm at an aircraft.

Civil Liability |

Class D Felony

Fine & Imprisonment of up to 5 years imprisonment

Class E Felony Fine & Imprisonment of up to 4 years imprisonment

Class E Felony Fine & Imprisonment of up to 4 years imprisonment

Monetary Damages

|

| California Penal Code | Shooting Drone with Shotgun

|

Penal Code 246.3 PC

1. 2. Willfully discharge a firearm, in a grossly negligent manner, which could result in someone's injury or death

Penal Code 246 PC

Maliciously and willfully fire a firearm at: An occupied aircraft**[2]

Penal Code 594 PC Vandalism: Maliciously commits any of the following acts with respect to any real or personal property not his or her own: (2) Damages; (3) Destroys

Crime of Carrying a Loaded Firearm in Public

Civil Liability |

Misdemeanor or Felony depending on facts

Misdemeanor – 1 Year in jail – Fine up to $ 1,000

Felony – 16 months – 4 years in jail.

Fine up to $ 10,000

Misdemeanor 6 – 12 Months imprisonment

Felony 3– 7 years imprisonment

Fine up to $ 10,000 Damage over $ 400.00 Fine up to $ 10,000.00 1 Year County Jail

Damage up to $ 10,000.00 Fine up to $ 50,000.00

Fine up to $ 10,000.00 1 Year County Jail

Monetary Damages |

TABLE 12-3: GLOBAL LEGAL EXAMPLES[3]

| Country | Countermeasure | Prohibition or Rule | Penalty |

| United Kingdom | GPS Jamming or signal interference | Wireless Telegraphy Act 2006

UK Public General Acts, 2006 c. 36, Part 2 Chapter 4 Unauthorized use etc. of wireless telegraphy station or apparatus |

Fine of up to £ 250,000; and

5% Gross Revenue Imprisonment up to 2 years |

| Misleading messages (spoofing), Interception | Wireless Telegraphy Act 2006

UK Public General Acts, 2006 c. 36, Part 2 Chapter 4 A person commits an offence if, by means of wireless telegraphy, he sends or attempts to send a message to which this section applies. (a) is false or misleading; and (b) is likely to prejudice the efficiency of a safety of life service or to endanger the safety of a person or of a ship, aircraft or vehicle.

|

Fine of up to £ 250,000; and

5% Gross Revenue Imprisonment up to 2 years |

|

| Computer Hacking | Computer Misuse Act of 1990

|

Up to 2 years Imprisonment and up to £ 5,000 Fine | |

| Shooting UAV with illegal weapon | Section 5(2A)(c) of the Firearms Act 1968 | · For possession, purchase or acquisition - 10 years imprisonment.

· For manufacture, sale of transfer - Life imprisonment.

|

|

| Chapter 27, Part 1 (16) Firearms Act of 1968

Possession of firearm with intent to endanger life or cause serious injury to property Chapter 27, Part 1 (18) Firearms Act of 1968 Carrying firearm with criminal intent Chapter 27, Part 1 (19) Firearms Act of 1968 Carrying a Firearm in a Public Place

Chapter 27, Part 1 (20) Firearms Act of 1968 Trespassing with a Firearm

|

· 6 months – 4 years imprisonment | ||

| Damaging or attempting to damage a UAV | Criminal Damage Act 1971 Chapter 48 Part 1 (1), (2)

Destroying or damaging property Criminal Damage Act 1971 Chapter 48 Part 3 (a), (b) Possessing anything with intent to destroy or damage property

|

· | |

| Russian Federation | Using a weapon to destroy a UAV | Chapter 27. Crimes Against Traffic Safety and the Operation of Transport Vehicles

Article 263. Violation of the Rules for Traffic Safety and Operation of the Railway, Air, Sea and Inland Water Transportation Systems, as Well as of the Underground Railroad |

· 100,000 – 300,000 Rubles Up to 4 Years in prison or 2 years in labor camp. |

| Article 267. Putting out of Commission Transport Vehicles or Communications

1. Destruction, damage, or putting out of commission transport vehicles, warning devices, communications or communications facilities, or any other transport equipment, and likewise blocking transport communications, if these acts have involved, by negligence, the infliction of grave injury to human health, or the infliction of large damage |

100,000 – 300,000 Rubles Up to 4 Years in prison or 2 years in labor camp. | ||

| Article 271.1. Breaking the Rules for Using the Airspace of the Russian Federation | Up to 7 years imprisonment | ||

| Using GPS Jamming, Radio interference of other disabling of computer systems or hacking | Chapter 28. Crimes in the Sphere of Computer Information

Article 272. Illegal Access to Computer Information 1. Illegal access to legally protected computer information, if this deed has involved the destruction, blocking, modification or copying of computer information |

fine up to 200 thousand rubles, , or with restraint of liberty for a term of up to two years, or with compulsory labor for a term of up to two years, or with deprivation of liberty for the same term. | |

| Article 273. Creation, Use, and Dissemination of Harmful Computer Programs

1. Creation, dissemination or use of computer programs or another computer information, which are knowingly intended for unsanctioned destruction, blocking, modification or copying of computer information or for balancing-out of computer information security facilities - |

fine up to 200 thousand rubles, , or with restraint of liberty for a term of up to two years, or with compulsory labor for a term of up to two years, or with deprivation of liberty for the same term. | ||

| Article 281. Sabotage 1. Perpetration of an explosion, arson, or of any other action aimed at the destruction or damage of enterprises, structures, transport infrastructure facilities and transport vehicles, or vital supply facilities for the population, with the aim of subverting the economic security or the defense capacity of the Russian Federation | Punishable by deprivation of liberty for a term of ten to 15 years | ||

| Australia | Damaging or Shooting A Drone | 1 Crimes (Aviation) Act 1991 –No. 139, 1991

Compilation No. 257 Destruction of aircraft (1) A person must not intentionally destroy a Division 3 aircraft.

|

Penalty: Imprisonment for 14 years. |

| Dangerous Use of Firearms Section 93 H (2) of the Crimes Act of 1900

|

10 Years Imprisonment | ||

| Endangering safety of aircraft—general

(1) A person who, while on board a Division 3 aircraft, does an act, reckless as to whether the act will endanger the safety of the aircraft, commits an offence. section 195 of the Crimes Act 1900 THE OFFENCE OF MALICIOUS DAMAGE The offence of Malicious Damage is contained in section 195 of the Crimes Act 1900

|

Penalty: Imprisonment for 10 years

|

||

| GPS Jamming | Prohibition relating to RNSS jamming devices

Under section 190 of the Act, the ACMA declares that:

|

Penalties for breaching the rules can be a fine of up to $1.05 million or up to 5 years in prison | |

| Radio Signal Interference | Use of Non-approved Radio

Transmission devices |

Fines of up to $25,200 up to two years in prison |

Sources: (Federal Aviation Administration Office of Airports Safety and Standards, 2016) (Secretary of State for the Home Department, 2019) (Russian Federation, 1996) (United Nations, 2019) (United Nations, 2019)

CAN C-UAS BE REGULATED? THE C-UAS FABLE

The current paucity of global C-UAS regulation is not only a product of the fact that UAS legislation is still in its formative stages, but it is also equally a result of the speed with which UAS, and consequently C-UAS technology is developing.

When considering whether and to what extent to regulate C-UAS technology, I turn to one of my favorite legal fables where the moral of the story is that when legislating, less can be more, particularly apropos when considering C-UAS regulation, more specifically micro-drones, and swarms.

In an attempt to eliminate a problem with pesky flies, the local town decides to deploy a solution to make life more pleasant for its residents. Although there are many more possible solutions, the village elders provide the three which they feel to be representative of different levels of risk vs. reward.

Choice 1:

Provide each household a fly swatter to give them a tool to stop flies coming into their homes.

Result:

Somewhat useful, but in the long run, not a solution that will eliminate the nuisance.

Unintended Consequence:

Sore elbow, broken items in the home, the species survives intact.

Figure 12-3 Cockroaches and Nuclear Bombs

Source: (Daftardar, Depressed Man Meme, 2019) & (Daftardar, Can Cockroaches Really Survive A Nuclear Explosion?, 2015)

Choice 2:

Use aerial or water sprayed dispersion of pesticides.

Result:

Most flies eliminated, no method to contain ingestion by unintended targets or limit environmental pollution in a safe & effective manner.

Unintended Consequence:

May cause side effects to the population of humans, pets, farm animals, plant life, crops, air purity, and water. Causing a cascading series of complications ranging from remediating the environmental damage to treating generations of diseased humans, animals, and plants.

Choice 3:

Deploy a unique acoustic wing-speed signature detection technology for the species of fly native to the region where the village is situated. Once confirmed, a radio frequency countermeasure would cause the fly to die from brain injury within one minute.

Result:

Current species of native flies mostly eliminated.

Unintended Consequence:

Flies evolve where their wing-speed changes, and their acoustic sensitivity and brains become immune to the technology. Additionally, aircraft, radios, GPS, and other technologies adversely affected, causing mass disruptions to daily life.

Primum Non Nocere - First Do No Harm

The Latin phrase "Primum non Nocere" - First Do No Harm, borrowed from the field of medicine seems to be a worthy objective for C-UAS legislation. C-UAS covers a broad spectrum of kinetic and non-kinetic measures taken to destroy, disable, confuse, hijack, or otherwise interfere with the intended operation of an Unmanned Aerial System. A C-UAS tactic might be as simple as throwing a stone at a drone or as complex as introducing malware into its operating systems and everything in between. My talented co-authors more than amply discuss these technologies and tactics in other chapters of this text. For our purposes, it is necessary to determine (1) whether C-UAS regulation on a globally functional basis is possible? (2) If it was possible, how would such law impact the rights of individuals, technology companies, the respective national security interests of each nation, individual security rights and cultural differences between countries around the globe; and (3) how are inevitable conflicts in law resolved given the inherently international nature of UAS and C-UAS technology?

While the United States and other nations are currently studying the issue, as of late November 2019, it is safe to summarize the current global C-UAS specific legislation landscape as non-existent. (Jason Snead, 2018) Since UAS technology is currently being used in both military and civilian applications worldwide, NGO's such as the United Nations ("UN") and individual nations are to create effective C-UAS regulation, some degree of commonality must exist.

What is meant by commonality? For our examination, commonality means uniform foundational principles that must be recognized globally. Much like a Geneva Conventions for warfare, this policy is best run by an NGO, the most logical being the UN. Unfortunately, history teaches than UN enforcement is inherently challenging due to having 193 member states, each with separate values, cultures, religions, political and economic systems. (United Nations, 2019) Add the all too common realities of formal and informal military conflict, and it becomes a certainty that nations will interpret the regulations in a manner that supports its objectives. Accordingly, a uniform global C-UAS law does not appear to present a viable option. However, the Geneva Conventions, Hague Conventions, War Crimes, Genocide, Ethnic Cleansing, International Humanitarian laws and adjudication thereof by the UN War Crimes Tribunal should be amended to include UAS and C-UAS activity warfare specifically. (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2016) (United Nations, 2019)

When technology becomes widely available and less expensive, not to mention remotely operable, it becomes attractive to those with nefarious intent. Add the capability to deliver biologic, chemical, and nuclear payloads, and the potential to be used as a Weapon of Mass Destruction by non-state actors becomes a frightening reality. (Office of the President of the United States, 2018)

Most nations eschew C-UAS specific legislation instead of choosing to provide-UAS authority to military, civil aviation, and homeland security functions and relying upon existing criminal statutes and aviation rules and regulations to control widespread C-UAS activity. The Federal Aviation Administration issued one of the most recent pronouncements on the subject on August 14, 2018. In short, the Law Enforcement Guidance letter discussed the primacy of the Federal Governments' role in any C-UAS activity in the United States with state and local Law Enforcement being invaluable partners in ensuring safe drone operation. According to the guidance letter, Law Enforcement’s role in C-UAS activity should be in accord with the process described by the acronym D-R-O-N-E:

- Direct attention outward and upward, attempt to locate and identify individuals operating the UAS. Look at windows/balconies/rooftops. Law enforcement is in the best position to locate the suspected operator of the aircraft, and any participants or personnel supporting the operation.

- Report the incident to the FAA Regional Operations Center (ROC). Follow-up assistance can be obtained through FAA Law Enforcement Assistance Program (LEAP) special agents. Immediate notification of an incident, accident, or other suspected violation to one of the FAA ROCs, located around the country, is valuable to the timely initiation of the FAA’s investigation. These centers are manned 24-hours a day, seven days a week, with personnel trained to contact appropriate duty personnel during non-business hours when there has been an incident, accident, or other matter that requires timely response by FAA employees.

- Observe the UAS and maintain visibility of the device. Note that the battery life of a UAS is typically 20 to 30 minutes. Look for damaged property or injured individuals. Local law enforcement is in the best position to identify potential witnesses and conduct initial interviews, documenting what they observed while the event is still fresh in their minds. Administrative proceedings often involve very technical issues; therefore, we expect our own aviation safety inspectors will need to interview most witnesses. During any witness interviews, use of fixed landmarks depicted on maps, diagrams, or photographs, immeasurably help in fixing the position of the aircraft, and such landmarks should be used to describe lateral distances and altitude above the ground, structures or people (e.g., below the third floor of Building X; below the top of the oak tree located at Y; or any similar details that give reference points for lay witnesses). We are mindful that in many jurisdictions, state law may prohibit the transmission of witness statements to third parties, including the FAA. However, capturing the names and contact information of witnesses to provide to the FAA will also be extremely helpful.

- Notice features. Identify the type of device, whether it is fixed wing or multi-rotor, its size, shape, color, and payload, such as video equipment, and the activity of the device. Pictures taken in close proximity to the event are often helpful in describing light and weather conditions, any damage or injuries, and the number and density of people, particularly at public events or in densely populated areas.

- Execute appropriate action. Follow your policies and procedures for handling an investigation and securing a safe environment for the public and first responders.

- It must be noted, any investigations conducted by LEAs should be in accordance with local or state authorities, as the FAA’s statutes and regulations do not permit their use as a basis for LEAs to conduct investigations. (Federal Aviation Administration, 2018)

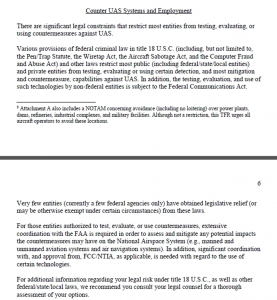

In order to reinforce current C-UAS restrictions, a recent FAA Law Enforcement Guidance letter cites specific Federal laws and regulations which are implicated when an unauthorized person engages in C-UAS activity in the United States. (Figure 12-4)

By way of comparison, the United Kingdom allows Law Enforcement a broader use of C-UAS technology and tactics including DTI (Detect Track and Identify) technology, and effector technology which can disable hostile drones. In a recent Counter Unmanned Aircraft presentation given to Parliament in October 2019, the British Home Department established a multifold strategy for C-UAS preparation and capability.

The stated objective of the plan is:

- 1. Developing a comprehensive understanding of the evolving risks posed by the malicious and illegal use of drones;

- Taking a ‘full spectrum’ approach to deter, detect and disrupt the misuse of drones;

- Building strong relationships with industry to ensure their products meet the highest security standards and,

- Empowering the police and other operational responders through access to counter-drone capabilities and effective legislation, training and guidance.(Secretary of State for the Home Department, 2019)

Figure 12-4: FAA Law Enforcement Guidance

Source: (Federal Aviation Administration, 2018)

The current UK C-UAS policy differs from that of the United States in that it provides for a more active C-UAS role given to Law Enforcement agencies:

“The police are able to legally deploy a range of DTI and counter-drone effector systems. We will develop options for the creation of a UK national counter-drone capability that will reduce our domestic reliance on defence capability to respond to the most challenging drone security incidents and will allow the police to protect national iconic events, or support crisis response. We will identify the most appropriate equipment and resource to procure and deliver this capability.” (Secretary of State for the Home Department, 2019)

While current C-UAS regulations and enforcement regimes vary significantly, given time and study, it is likely that more certainly will come to C-UAS practice. The challenge facing C-UAS practitioners will be multi-fold. Off the shelf obsolescence, Counter- Counter-UAS technology will inevitably be incorporated into many UAS just as chaff, flares, jamming, DIRCM (Directed Infrared Counter Measures), and other technologies rapidly developed to counteract anti-aircraft technology from the dawn of military aviation up to today.

Students must account for the reality that a measure-countermeasure dynamic will present challenges to any scheme of C-UAS legislation or regulation. Therefore, it is incumbent upon those who enact C-UAS laws to avoid the temptation of focusing upon specific technologies or tactics instead of focusing upon the establishment of general principal legislation.

For example, a regulation that proscribes C-UAS technology or tactics which are likely to endanger the public nationwide is far more flexible than a statute that prohibits the use of C-UAS technology in or near cities with a population over 100,000.

The principle of legislative generality was affirmed by the Government of Victoria, Australia when it issued the following guidance:

“Regulation of specific activities, industries or professional groups is a last-resort option. Preference will be given to promoting industry self-regulation and best practice, including codes of conduct, assessing whether existing broader legislation (State or Commonwealth) applies to particular cases, using other non-legislative methods (e.g. government provision of information) to address concerns. (DTF 2005, p. 1–7) (Consumer Affairs Victoria, 2006)

Regulating technology can have many unintended consequences, which were articulated by Christopher Fonzone and Kate Heinzelman in a 2018 opinion piece regarding legislating Artificial Intelligence.

“Decisions made today may have substantial ripple effects that legislators could easily miss on the development of AI technology down the road. Who could have possibly imagined the full implications of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act when it was enacted in 1996? Or the effect of the Electronic Communication Privacy Act’s warrant requirement for emails less than 180 days old in 1986? Early legislative enactments about new technologies tend to persist.” (Christopher Fonzone, 2018)

There are no clear answers when it comes to ethics, technology, warfare, terrorism, and crime. C-UAS Students, Practitioners, and Regulators would be wise to remember that job 1 in public safety and national defense is first not to harm those you seek to protect.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS - Self Defense

Recently Hollywood has been capturing the imagination of audiences globally with thrillers involving UAS attacks by traditional and non-traditional combatants, terrorists, and other bad actors. The 2019 film, "Angel Has Fallen" takes quite a bit of license, however, is undoubtedly demonstrative of how UAS technology, in the hands of a bad actor, could wreak havoc on society. (Waugh, 2019) The use of mobile launched mini-drone swarm technology presents a growing threat to all society. Let's hope it's a case of art imitating imagination instead of creativity imitating life.

Figure 12-5: Angel Has Fallen

Source: (Waugh, 2019)

Films including Star Trek, War Games, Star Wars, Runaway, and Terminator are a few examples of films that examine AI, Automation, Unmanned technology, and the attendant risks they pose when falling into the wrong hands or become out of control due to a fault or defect. In a world where weapons of war have been finding their way off the battlefield and onto the streets, we must be prepared and assume the reality that UAS technology will also be a prime target for the black-market profiteers. Even worse, UAS technology designed for the hobbyist, farming or other non-military functions is currently flooding the market at low prices. This new affordability begs the question, if technology falls into the hands of those who present asymmetric threats, and can appear to be part of everyday life, is it ethical for the government to prohibit individuals from engaging in self-defense? Isaac Asimov, the noted writer, and scientist first introduced and right of self-defense against automated technology ("robots") in the short story Runaround published in 1942.

Figure 12-6: Asimov’s 3 Laws for Robots

Source: (Asimov, 1942)

To allow for an orderly introduction of robotics into our lives, Asimov, a visionary futurist, created the "The Laws for Robots."

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

He later introduced a zeroth law which stated:

- A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm. (MIT Technology Review, 2014)

Subsequently, other scholars examined Asimov's three laws in the context of the drone age, where remotely piloted or autonomous aircraft are now capable of inflicting harm to humans on a massive scale. Ulrike Barthelmess, Koblenz Ulrich Furbach expanded upon this concept when they wrote in a paper discussing whether Asimov's laws of robotics in 2014:

“But we also should mention that there do exist autonomous vehicles and robots designed per se to harm humans. Military robots or autonomous drones are aiming explicitly at violating Asimov’s laws. What we desperately need are legal and ethical rules for the commitment of robots. We can see this from the debate around drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemeni Somali. According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism there is a kind of covert drone war in those countries. Drones are used to strike against targets in countries, without being officially in war according to the international law of armed conflict. More or less autonomously operating drones are destroying targets i.e. humans, which are associated with terrorism. And as can easily be imagined there is a significant number of civilians killed or injured as collateral damage. We want to argue that a similar procedure would not so readily be accepted by the world public, if instead of drones manned aircrafts would be used. It seems as if there is much lower acceptance threshold to use robots instead of regular military forces for illegal or covert warfare.

Besides of moral and ethical considerations, this raises a lot of legal questions. Is it legal to strike targets with unmanned drones in a country which is not in a formal state of war with the owner of drones? Is it legal for a third-party country to support such an action, e.g. by delivering data for military reconnaissance or by hosting the pilots of the drones? In the context of this discussion it would be more likely to answer the question from the title as follows: It is not allowed to build and to use robots which violate Asimov’s first law.” (Barthelmess, 2014)

Currently, it is hard to establish whether a drone flying overhead is benign or a threat to the safety of those below. The stealthy nature and ability to deliver payloads, surveil or interrupt activities of normal daily life drones that pose a threat can often appear as harmless as a hobbyist learning to fly the gift they received for their birthday. With literally millions of drones flying daily, the reality is that no law enforcement strategy, much less C-UAS military deployment, can reasonably be relied upon to 100% protect military, domestic, and individuals from the risks posed by UAS technology. Students are strongly urged to read the 2015 article in the Connecticut Law Review entitled "Self-Defense against Robots and Drones." Although it is now four years later and the UAS industry continues to grow exponentially in the military, commercial and civilian applications alike, the subject of self-defense against drones lies at the heart of C-UAS regulation. The authors correctly observe that absent a reliable system that the everyday citizen can use to determine whether a UAV is a friend or foe, individuals must have, at least to a certain degree, the right of self-defense. (Colangelo, 2015)

Conclusions

While there will be no shortage of pain points in the creation of a robust yet flexible C-UAS legislative and jurisprudential scheme, students should consider the reality that no matter how broad the policy may be, a motivated attacker will always find a way to exploit it. One need look no further than to constant friction between those who want to make certain classes of firearms illegal, and those who feel the right is a natural inheritance in countries such as the United States. Both make valid arguments yet were either side to prevail; those who are intent on harming will find a way to legally or illegally acquire a weapon. As we head further into the age of ubiquitous automation, there will be no shortage of debates about how best to regulate the legal and prevent the illegal use of the technology. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered a speech in 1963 when he discussed the challenge of legislating morality, as opposed to regulating behavior:

“Religion and education must play a great role in changing the heart. But we must go on to say that while it may be true that morality cannot be legislated, behavior can be regulated. It may be true that the law cannot change the heart, but it can restrain the heartless. It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me and I think that is pretty important, also.” (Dr. Martin Luther King, 1963)

Those who seek to engage in a career in the UAS / C-UAS field will undoubtedly have to confront this challenge regularly. Whether you are creating CUAS technology, deploying that technology, or designing strategies, the result of what you do will inevitably have a long-lasting consequence to humanity. Risk, reward, cost, and morality are but a few of the factors you will have to balance while the speed of new technology will make the ground beneath your feet feel like a treadmill moving 100 miles per hour.

No matter how good the technology, strategy, or defense, a motivated actor will find a way to exploit vulnerabilities inherent within it. So too is the case when legislating and regulating C-UAS activity. Every exigency, contingency, circumstance, and location will challenge the applicability of the law, not to mention possible provide a means for malevolent actors to exploit it to inflict great harm legally. Laws can inhibit the development of technologies that may offer more safety, certainty, and clarity to the field of UAS / C-UAS jurisprudence, and so knee-jerk, reactionary rules can do more harm than good. The best course of action? Think for today but be flexible enough to understand the consequence tomorrow. No law can be perfect, particularly when it comes to technology in its infancy.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

- If the farmer in Figure 12-1 shot down the drone flying near his farm, only to find the payload was a vial of liquid with a timer attached. Thankfully the buckshot from the shotgun and the fall to earth did not damage the vial ort timer. The farmer immediately calls authorities who respond and disarm the timer. They rush the drone away to a secure facility where they discover that vial contained an aerosolized form of the Ebola virus. But for the farmer's action, thousands may have died. Should he be charged with violating the various statutes listed in Figures 12-3 – 12-5 above?

- Would your opinion change if the buckshot damaged the vial and let the virus escape into the atmosphere? What if the target location was 20 miles away with a dense population while the population within 5 miles of his farm was under 100?

- Imagine the drone launcher from "Angel has fallen," as depicted in Figure 12-7, was pulling up to a remote area within proximity of Camp David, Maryland. Further, assume that a C-UAS hobbyist, uncertain of the law, was nearby and coincidentally testing a new C-UAS technology using magnetized plasma energy. Despite excellent efficacy, its components are military-grade and, therefore, illegal for a citizen to possess. Understanding the fact that Camp David is near and not seeing any indicia of Secret Service or other lawful entities on the launcher vehicle, he deploys the plasma energy weapon, disables the swarm, and saves the president, his family, and those in protection party. Should the hobbyist be treated as a criminal or a Good Samaritan?

- What if the scenario in number 3 above was the same, and the president was safe; however, the plasma energy cause three helicopters overhead to lose computer-assisted guidance, power and control surface function resulting in all three crashing and the lives of 16 agents were lost. Should the hobbyist be held criminally responsible?

References

Asimov, I. (1942, March). runaround. Astounding Science Fiction, pp. 94-103.

Barthelmess, U. &. (2014). Do we need Asimov's Laws?. arXiv - Cornell University, 9-11.

Christopher Fonzone, K. H. (2018, February 26). Should the government regulate artificial intelligence? It already is. Retrieved from The Hill: https://thehill.com/opinion/technology/375606-should-the-government-regulate-artificial-intelligence-it-already-is

Colangelo, A. M. (2015). Self-Defense Against Robots and Drones. Connecticut Law Review, 10-30.

Consumer Affairs Victoria. (2006). Choosing between general and industry specific legislation. Melbourne: Consumer Affairs Victoria.

Daftardar, I. (2015, June 26). Can Cockroaches Really Survive A Nuclear Explosion? Retrieved from Science ABC: https://www.scienceabc.com/eyeopeners/revealed-can-cockroaches-really-survive-nuclear-explosions.html

Daftardar, I. (2019, November 11). Depressed Man Meme. Retrieved from images-wixmp-ed30a86b8c4ca887773594c2.wixmp.com: https://images-wixmp-ed30a86b8c4ca887773594c2.wixmp.com/f/db28749d-3a5e-4956-9e70-ef417f1f8b21/d5hdmki-379818b5-1b65-4420-8639-9697faa9dcb1.jpg?token=eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJpc3MiOiJ1cm46YXBwOjdlMGQxODg5ODIyNjQzNzNhNWYwZDQxNWVhMGQyNmUwIiwi

Dr. Martin Luther King, J. (1963, December 18). Speech at Western Michigan University. Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA.

FAA UAS Center of Excellence. (2017). FAA UAS Center of Excellence Task A4: UAS Ground Collision Severity EvaluationRevision 2. Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration.

Federal Aviation Administration. (2018). Law Enforcement Guidance For Suspected Unauthorized UAS Operations - Version 5. Washington, DC: United States Department off Transportation.

Federal Aviation Administration Office of Airports Safety and Standards. (2016, July 2018). Airport Safety Media. Retrieved from FAA.Gov: https://www.faa.gov/airports/airport_safety/media/attachment-1-counter-uas-airport-sponsor-letter-july-2018.pdf

International Committee of the Red Cross. (2016, October 19). What are the rules of war and why do they matter? Retrieved from International Committee of the Red Cross: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/what-are-rules-of-war-Geneva-Conventions

Jason Snead, J.-M. S. (2018, April 16). Establishing a Legal Framework for Counter-Drone Technologies. Retrieved from The Heritage Foundation: https://www.heritage.org/technology/report/establishing-legal-framework-counter-drone-technologies

Junkin Media . (2016, October 23). Angry farmer shoots down drone hovering over his garde. Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Michael Hamann. (2018, November 18). Can You Legally Counter a Drone. Retrieved from Police MAgazine: https://www.policemag.com/486684/can-you-legally-counter-a-drone

MIT Technology Review. (2014, May 16). Do We Need Asimov's Laws? Retrieved from MIT Technology Review: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/527336/do-we-need-asimovs-laws/

Nichols, R. K., Mumm, H. C., Lonstein, W. D., Ryan, J. J., Carter, C., & and Hood, J.-P. (2019). Unmanned Aircraft Systems in the Cyber Domain. Manhattan, KS: New Prairie Press.

Office of the President of the United States. (2018). National Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism. Washington, DC: United States of America.

Russian Federation. (1996, June 13). Criminal Code of the Russian Federation No. 63-FZ of June 13, 1996 (as amended up to Federal Law No. 18-FZ of March 1, 2012). Criminal Code of the Russian Federation. Moscow, Russian Federation: Russian Federation.

Secretary of State for the Home Department. (2019). UK Counter-Unmanned Aircraft Strategy. London: HM Government.

United Nations. (2019, November 15). Member States. Retrieved from United Nations: https://www.un.org/en/member-states/index.html

United Nations. (2019, October 29). UN Documentation: International Law. Retrieved from Dag Hammarskjold Library: https://research.un.org/en/docs/law/courts

Waugh, R. R. (Director). (2019). Angel Has Fallen [Motion Picture].

West, H. S. (2019, March 16). Six Ways to Disable a Drone. Retrieved from Brookings: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2016/03/16/six-ways-to-disable-a-drone/

[1] It is notable that beginning on 2016 Title 49 of the U.S. Code was amended to establish a pilot program for C-UAS mitigation at and around airports and critical infrastructure.

[2] The issue of whether a UAV qualifies as an “occupied aircraft” is currently unclear

[3] The survey of laws listed in tables 12-1, 12-2 and 12-3 are by no means complete in terms of applicable laws within the respective jurisdictions listed or the overall global C-UAS regulatory framework.