Chapter 7: UAS Area / Airspace Denial

J.P. Hood

Student Learning Objectives: The student will obtain an understanding of how state entities deny potential known and unknown adversaries from gaining access via UAS and air assets into a protected area, resource or installation. Through the use of real-world examples and case studies, the student will be able to visualize and understand the intricacies and planning required for state and local actors to adequately protect an area from possible intrusion, exploitation and attack.

Key Concepts:

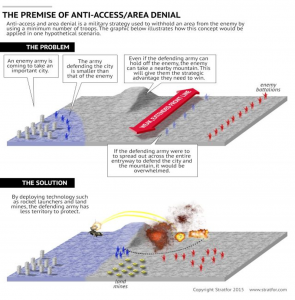

A2 / AD (Anti-Access / Area Denial) is primarily designed to prevent or constrain the deployment of opposing forces into an area of operations

Anti-Access: Denying an adversary the ability to enter and operate military forces near, into or within a contested region.

Area-Denial: Used to reduce freedom of maneuver once an adversary is within an area of operations.

IADS (Integrated Air Defense Systems)

Simply put, the act of an adversary to work against the actions of another defines what anti-access or area denial environments are. More formally, the U.S Department of Defense (DoD) Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC) defines these terms: “Anti-access (A2) refers to those actions and capabilities, usually long-range, designed to prevent an opposing force from entering an operational area. Area denial (AD) refers to those actions and capabilities, usually of shorter range, designed not to keep an opposing force out, but to limit its freedom of action within the operational area.” (Cuddington, 2015 )

Figure 7-1 The Premise of Anti-Access / Area Denial

Source: (Stratfor, 2019)

Some examples of existing and emerging A2AD capabilities:

- Multi-layered integrated air defense systems (IADS), consisting of modern fighter/attack aircraft, and fixed and mobile surface-to-air missiles, coastal defense systems,

- Cruise and ballistic missiles that can be launched from multiple air, naval, and land-based platforms against land-based and maritime targets,

- Long range artillery (LRA) and multi launch rocket systems (MLRS),

- Diesel and nuclear submarines armed with supersonic sea-skimming anti-ship cruise missiles and advanced torpedoes;

- Ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) force,

- Advanced sea mines

- Kinetic and non-kinetic anti-satellite weapons and supporting space launch and space surveillance infrastructure,

- Sophisticated cyber warfare capabilities,

- Electronic warfare capabilities,

- Various range ISR systems,

- Comprehensive reconnaissance-strike battle networks covering the air, surface and undersea domains; and

- Hardened and buried closed fiber-optic command and control (C2) networks tying together various systems of the battle network,

- Special Forces

(Erdogan, behorizon.com)

Recent Rise in A2-AD Ideologies and Challenges

As potential near peer adversaries to the US such as China, Russia, Iran and North Korea continue to gain technological ground and modernize multi layered defense networks, the US DoD and State Department have realized that control of the commons will soon be challenged and an increased understanding of A2-AD concepts is necessary in order to develop ways to mitigate, penetrate and exploit adversarial defense networks. The US’s continued reliance on UAS as platforms to act as ISR and communications relays as well as deliver precision guided munitions has proven to be a more realistic way to counter the growing security threats posed by ever more robust adversarial A2-AD systems. Nathan Freier from the Centers for Strategic and International Studies effectively codified through a series of question and answers why A2-AD concepts continue to remain a major theme at the forefront of military operational planning.

From the widest strategic perspective, U.S. access challenges manifest across traditional instruments of power. To the extent that these challenges adversely affect the security and prosperity of the United States and its allies, an open and stable international system, and/or freedom to transit the global commons, they will require coordinated U.S. government/allied responses to restore access. By definition, this will routinely involve military forces. (Freier, 2012)

This is not meant to suggest that all access challenges are military in origin and character. In the Asia-Pacific region, for example, China is as much or more an active political and economic challenger—seeking to raise myriad barriers to U.S. influence—as it is a military competitor. Likewise, in the Middle East, Iran has some dangerous military capabilities but successfully avoids direct military confrontation with the United States, advances its interests, and limits U.S. freedom of action most often through cost-imposing political subterfuge. What is certain, however, is that when adversaries effectively combine political, economic, and informational tools with important military capabilities, the access challenge becomes more acute and potent. (Freier, 2012)

U.S. military forces have a unique responsibility in helping secure access during times of peace, increased hostilities, and open conflict. The latter is the most demanding and, as of late, the subject of the greatest body of conceptual work. Under routine circumstances, maintenance of credible deterrent capabilities forward in key regions provides a stabilizing influence, actively underwrites the security of U.S./partner interests, and secures a concrete platform from which to expand presence and conduct operations in the event of heightened tensions or hostilities. (Freier, 2012)

In the event of war or major violent conflict, U.S. forces will face a variety of A2/AD challenges that will originate both from the hostile designs of thinking adversaries and from the “unstructured” lethality of contagious instability. In virtually every instance, forward-stationed U.S. forces will be insufficient to overcome lethal or fundamentally disruptive A2/AD challenges and effectively resolve the crisis by themselves. Therefore, future combat operations—whether coercive air and sea campaigns or more wide-ranging joint interventions—will require the United States and its partners to project substantial military capability over considerable strategic and operational distances. A2/AD challenges frustrate our ability to do so. (Freier, 2012)

Thus, at the “business end” of opposed operations, U.S. forces will increasingly compete with a diverse collection of adversaries for dominance across multiple domains—air, sea, land, space, and cyberspace. This will often occur without the benefit of extensive fixed U.S. regional basing and with “local” U.S. infrastructure under substantial pressure from hostile action. As a consequence, the character of specific lethal access challenges, their diversity, and their sophistication will differ significantly. In combination, the real constraints of finite military capability, the increasing lethality of virtually every conceivable contingency environment from peace operations to regional war, and lower U.S. risk tolerance make deep thought about lethal or fundamentally disruptive A2/AD challenges an urgent strategic priority. (Freier, 2012)

Anti-Access Challenges

To U.S. strategists, A2 challenges are intended to exclude our forces from a foreign theater or deny effective use and transit of the global commons. More broadly, A2 challenges might first involve political and economic exclusion, where competitor states actively attempt to deny the United States the broad political and economic influence it has long enjoyed. In military terms, this may translate into blanket denial of basing, staging, transit, or over-flight rights. (Freier, 2012)

Under more hostile circumstances, lethal A2 instruments include sophisticated longer-range adversary capabilities and methods like ballistic missiles, submarines, weapons of mass destruction, and offensive space and cyberspace assets. Equally dangerous but less technical A2 methods might include terrorism or proxy warfare employed by U.S. opponents to open alternative “fronts,” distract attention, and impose excessive costs politically. (Freier, 2012)

Hostile A2 capabilities and methods are intended first to see U.S. risk calculations breach “high” or “unacceptable” levels during planning in order to prevent U.S. regional intervention altogether. But, in the event of active hostilities, adversaries would employ their lethal A2 assets from a distance to keep the United States at arm’s length, perhaps deny introduction of U.S. forces and capabilities in substantial numbers, and barring either outcome, exact prohibitively high costs on the United States when and if U.S. forces attempt to breach an opponent’s A2 defenses. Given China’s increased assertiveness, current military capability, and raw potential, an acute, sophisticated, and comprehensive A2 challenge is emerging in Asia. There is clearly some grand strategic risk associated with excessively militarizing the nature of the competition between the United States and China, as the locus of real competition may lie substantially outside the reach of DoD and the military instrument. (Freier, 2012)

Area Denial Challenges

Over the near to mid-term, lethal area denial (AD) challenges present U.S. strategists with the most prolific barriers to effective theater entry and operation. Every conceivable contingency employment of air, sea, or ground forces will need to overcome significant AD obstacles. Lethal AD threats manifest at close range. Their effects begin accruing as U.S. forces enter a hostile or uncertain theater to conduct joint operations, and in the end, they complicate our attempts to establish an effective presence in, over, or in range of an adversary’s territory or interests. Lethal or disruptive AD challenges are present and can attack U.S. vulnerabilities in all five key domains—air, sea, land, space, and cyberspace.

They do so first by providing the means to physically resist U.S. entry into theater. Subsequently, they limit freedom of action once U.S. forces have arrived. Then, they frustrate our efforts to rapidly achieve favorable strategic and operational outcomes. And, finally, they threaten to impose very high costs on U.S. forces should extended military operations become unavoidable. Like A2 challenges, AD threats can poison U.S. risk calculations well before the initiation of an operation by increasing the mission’s perceived degree of difficulty. After entry, AD challenges force U.S. decisionmakers to persistently question the mounting costs associated with continued operations. (Freier, 2012)

Lethal AD capabilities range from the sophisticated to the crude but effective. They include cruise and ballistic missiles; weapons of mass destruction; mines; guided rockets, mortars, and artillery; electronic warfare; and short-range/man-portable air defense and anti-armor systems. Revolutions in information; personal computing, communications, and networking; and irregular and hybrid forms of warfare—combined with the proliferation of precision weapons and improvised battlefield lethality—substantially widen the universe of effective AD adversaries from individuals and loosely organized groups to sophisticated regional powers. Likewise, the networked mobilization of foreign popular, nonviolent resistance may also prove to be a significant challenge to freedom of action in the future as well. To the extent U.S. opponents can leverage all of these capabilities and methods both directly and through proxies, the more the AD challenge will expand geometrically. As noted above, an effective combination of political, economic, and informational methods with sophisticated lethal and/or disruptive AD capabilities will make any specific challenge more resilient and potent. (Freier, 2012)

Whereas lethal A2 challenges are virtually always the product of deliberate enemy design, AD challenges don’t have to be. They can be “structured” or “unstructured.” Iran’s hybrid “mosaic defense,” for example, is structured. Though highly unconventional, it is part of a coherent cost-imposing strategy. Its combination of ballistic and cruise missiles, unconventional naval forces, and hybrid ground defenses—matched with tight Persian Gulf geography, Iran’s physical depth, and its deep ties to regional proxies—offer a complex structured AD challenge that strategic and operational planners would have to account for in the event of hostilities. (Freier, 2012)

U.S. forces are likely to face unstructured AD challenges in the course of interventions conducted under conditions of widespread disorder, where local authorities have little or no control over outcomes. Imagine military operations conducted in the same Iran described above; this time, however, after failure of the regime and in the midst of an ongoing civil war. U.S. forces might face multiple competing adversaries all boasting some relatively sophisticated, disruptive, and lethal AD capability but employing it all haphazardly under no discernible centralized command and control, making comprehensive defeat more problematic. (Freier, 2012)

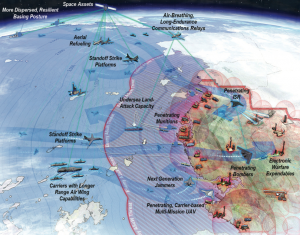

Figure 7-2 Overcoming Adversarial Defenses

Source: Image Attribute: Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC) in an Anti-Access, Area Denial Theatre/ Source: McNeal & Associates (Associates, 2019)

According to the “Air-Sea Battle” concept, the general U.S. solution to the A2/AD issue is to develop a network of integrated forces capable of defeating the enemy across all modern war fighting domains: air, sea, land, space, and cyberspace. (US Department of Defense, 2013) This concept recognizes that adversary forces will likely attack without warning and forward friendly forces will be in the A2/AD environment from the outset of hostilities and must provide an immediate and effective response. (Cuddington, 2015 )

Case Study: Countering Growing Chinese A2/AD in the Indo Pacific Region

The United States has long enjoyed “command of the commons”: worldwide freedom of movement on and under the seas and in the air above 15,000 feet, with the ability to deny this same freedom to enemies. This command has contributed to a remarkable era of military primacy for U.S. arms against potential state rivals. (Cuddington, 2015 )

Over the past few decades, state actors such as China have begun to establish themselves in the pacific region, challenging the US’s ability to project power in the region. China is one of the most significant A2/AD threats at this time. China not only deters the United States from deploying into the Western Pacific, but also threatens to disrupt nearby operations such as around Taiwan or the South China Sea. (Cuddington, Jeff, 2016)

While U.S. advanced fighters and bombers have inherent advantages against China’s defenses, these aircraft are not immune and are very limited in availability. A majority of American fighters, bombers, reconnaissance aircraft, and cruise missiles remain extremely vulnerable. China’s integrated air defense system is virtually impossible to penetrate with current U.S. fourth-generation aircraft. (Posen, 2003)

Furthermore, China is expected to increase its threat range with the development of the S-400 (currently operational) missile system, extending their air defense coverage out to over 200 nautical miles. (Cuddington, Jeff, 2016)

Many observers now fear that this era may be coming to an end in the Western Pacific. For more than a generation, China has been deploying a series of interrelated missile, sensor, guidance, and other technologies designed to deny freedom of movement to hostile powers in the air and waters off its coast. As this program has matured, China’s ability to restrict hostile access has improved, and its military reach has expanded. Many now believe that this “A2/AD” (anti-access, area denial) capability will eventually be highly effective in excluding the United States from parts of the Western Pacific that it has traditionally controlled. Some even fear that China will ultimately be able to extend a zone of exclusion out to, or beyond, what is often called the “Second Island Chain”—a line that connects Japan, Guam, and Papua-New Guinea at distances of up to 3,000 kilometers from China. A Chinese A2/AD capability reaching anywhere near this far would pose major challenges for US security policy. (Defense, 2006)

To avert this outcome, the United States has embarked on an approach often called AirSea Battle (ASB). Named to suggest the Cold War continental doctrine of “Air-Land Battle” (ALB), AirSea Battle is designed to preserve U.S. access to the Western Pacific by combining passive defenses against Chinese missile attack with an emphasis on offensive action to destroy or disable the forces that China would use to establish A2/AD. This offensive action would use “cross-domain synergy” among U.S. space, cyber, air, and maritime forces (hence the moniker “AirSea”) to blind or suppress Chinese sensors. The heart of the concept, however, lies in physically destroying the Chinese weapons and infrastructure that underpin A2/AD. As Chinese programs mature, achieving this objective will require U.S. air strikes against potentially thou- sands of Chinese missile launchers, command posts, sensors, supply net- works, and communication systems deployed across the heart of mainland China—some as many as 2,000 kilometers inland. Accomplishing this mission will require a major improvement in the U.S. Air Force’s and Navy’s ability to and distant targets and penetrate heavily defended airspace from bases that are either hard enough or distant enough to survive Chinese attack, while hunting down mobile missile launchers and command posts spread over mil- lions of square kilometers of the Chinese interior. The requirements for this mission are typically assumed to include a major restructuring of the Air Force to de-emphasize short-range fighters such as the F-35 or F-22 in favor of longer-range strike bombers; development of a follow-on stealthy long-range bomber to replace the B-2, and its procurement in far greater numbers than its predecessor; the development of unmanned long-range carrier strike aircraft; and heavy investment in missile defenses and information infrastructure. The result would be an ambitious modernization agenda in service of an extremely demanding military campaign to batter down A2/AD by striking targets deep in mainland China, far afield from the maritime domains to which the United States seeks access. (US Department of Defense, 2013)

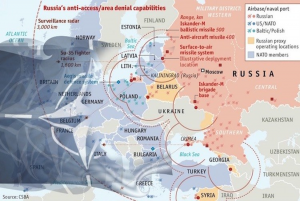

Figure 7-3 Air Space Denial: Russian A2AD Strategy and Its Implications for NATO

Source: (behorizon.org, russian-a2ad-strategy-and-its-implications-for-nato/ , 2019)

Integrated Air Defense System (IADS)

The integrated air defense system (IADS) threat today remains a formidable challenge to air operations in nearly any foreseeable major conflict. IADS modernization, coupled with significant advancements in multi- domain military operations (Cyber, Global C4ISR, Offensive Strike, Threats to Coalition Basing, etc.), poses a significant area denial threat to U.S. air dominance that was virtually guaranteed in past military operations. Fundamentally, the foundational pillars of the IADS kill chain have remained unchanged for decades; with mature processes and equipment widely fielded to perform indications and warning (I&W), find/fix, track, engage, and assessment functions. ((NASIC), 2019)

Battle Management Advancements: for the past 10+ years there has been significant advancement with adversary global C4ISR capabilities and their overall holistic approach to integrating disparate sources into a common, fused C4ISR infrastructure supporting IADS. While many advanced C4ISR concepts remain in their infancy, adversary current capabilities to process data globally in a timely, actionable manner poses a significant obstacle to U.S. global airpower and air operations. ((NASIC), 2019)

Weapons Control Advancements: since 2010, adversary IADS modernization has included deployment of long-range anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) weaponry, supported by a vast deployment of layered tactical systems to augment long-range capabilities. These modern weapon systems threaten nearly every aspect of our counter-IADS / suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD) capabilities. Many of the emerging capabilities focus on the denial of airborne ISR and increasing the threat to 4th /5th Generation aircraft, cruise missiles, precision guided munitions, and UAVs. ((NASIC), 2019)

Understanding Emerging Vulnerable Gap

The potential exists for significant future developments to occur in the following technologies and concepts that are emerging but are not yet fully integrated and or operational:

- (U) Hypersonic defense

- (U) Cyber-enabled IADS

- Roll-out of modern directed energy weapons; combating airborne platforms at tactical ranges

- Full integration of “Big Data,” artificial intelligence, and mature net centric IADS operations

While adversary IADS capabilities continue to advance and pose a significant threat to U.S. air dominance, there are still critical vulnerabilities at nearly every echelon. C4I dependencies and centralized processes permeate these systems – and create opportunities for exploitation. ((NASIC), 2019)

Russian A2AD Case Study

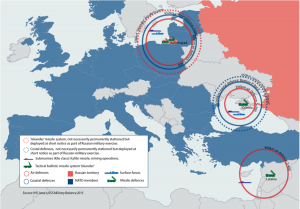

Russia’s recently deployed advanced A2AD capabilities such as; long range precision air defense systems, fighters and bombers, littoral anti-ship capabilities and ASW (Anti-Submarine Warfare), mid-range mobile missile systems, new classes of quieter submarines equipped with long range land attack missiles, counter-space, cyberspace, & EW weapons; and WMD assets in Kaliningrad in Black Sea and partly in Syria have changed the military environment. With additional deployments -thanks to modernization expected by 2020s- battlefield will be more complicated than ever. These A2AD capabilities allow Russia to have a new strategic buffer zone between NATO and Russia, but this time within Alliance` own territory. They provide the ability to target a large part of the Europe to influence, deter and deny NATO’s potential operations in the High North, Baltic, Black Sea and East Mediterranean regions. (Busch, 2016)

The figure below depicts only a part of the Russian A2AD capabilities.

Figure 7-4 Russian A2AD Strategy Against NATO

Source: HIS Janes; IISS Military Balance 2015 & (behorizon.org, russian-a2ad-strategy-and-its-implications-for-nato/ , 2019)

Current C-UAS A2AD Civil Applications

As the need for more complex area defense for countering illicit drone operations continues to grow, private industry has not forgotten the needs for companies and individual consumers to protect their personal and intellectual properties. Companies such as DeDrone and Drone Shield currently offer a range of integrable systems that are able to detect, track and deter commercial drones from entering private or localized airspace. The greatest risks to the public remain large open-air sporting venues / gatherings as well as domestic infrastructure / open to the air resources. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and US Customs and Border Protection will benefit greatly from using such technologies. Local integrated systems will be able to stop intruding drones from entering the US. These UAS have been reported carrying payloads containing contraband and narcotics. Drone Shield has developed Drone Sentry X that can intercept incurring drones. Federal prisons have also implemented similar systems from DeDrone in order to intercept and halt drone deliverables from entering a prison yard.

Figure 7-5 Drone Shield Drone Sentry

Source: (droneshield, droneshield.com/sentry, 2020)

Figure 7-6 Drone Sentry X

Source: (droneshield, dronesentry-x , 2020)

Conclusions

A2-AD and IADS are now center stage during all levels of operational planning conducted by the DoD. C-UAS considerations / technologies are the latest addition to planning and coordinating an effective area defense from aerial intrusions. While drones continue to operate in political grey areas focused on gaining access and intelligence, governments and military forces are continuing to seek non-kinetic technological means of tracking, denying and engaging these systems. Experts in C-UAS must be able to understand the unique challenges posed by fast moving systems with ever increasing standoff ranges. They must be able to recommend and employ systems that effectively counter these threats while at the same time adhere to international and domestic laws regarding vehicles in flight keeping the public safe from harm.

Innovative thinking at longer ranges will become more and more crucial. Advances in emerging technologies such as hypersonic vehicles that could potentially be delivered via UAS will continue to drive the need for a more dynamically integrated defense network(s). Decision processes will be forced to become that much faster in order to effectively defend against these new threats.

References

(NASIC), N. A. (2019, July 19 ). Emerging IADS Threats: Talking Points. DoD Periodical.

Associates, M. &. (2019, December). OPINION-Need-of-the-Hour-A2AD. Retrieved from www.indrastra.com: https://www.indrastra.com/2016/01/OPINION-Need-of-the-Hour-A2AD-002-01-2016-0084.html

behorizon.org. (2019, December). russian-a2ad-strategy-and-its-implications-for-nato/ . Retrieved from www.behorizon.org: https://www.behorizon.org/russian-a2ad-strategy-and-its-implications-for-nato/

behorizon.org. (2019, December). russian-a2ad-strategy-and-its-implications-for-nato/ . Retrieved from www.behorizon.org: https://www.behorizon.org/russian-a2ad-strategy-and-its-implications-for-nato/

Busch, K. a. (2016, February 09). No Denial: How NATO Can Deter Creeping Russian Threat. www.cer.org.uk/insights .

Cuddington, J. (2015 ). Intellignece Operations in Denied Area. At Home and Abroad: Thinking Through Conflicts and Conundrums .

Cuddington, Jeff. (2016, January ). Opinion: Need of the Hour: New Intelligence .

Defense, O. o. (2006). Annual Report to Congress: Military Power of the Peoples Republic of China . US DoD , pp. 21, 25. .

droneshield. (2020, January). dronesentry-x . Retrieved from www.droneshield.com: https://www.droneshield.com/dronesentry-x

droneshield. (2020, January). droneshield.com/sentry. Retrieved from www.droneshield.com: https://www.droneshield.com/sentry

Freier, N. (2012). The Emerging Anti-Access/ Area Denial Challenge. Center for Strategic and International Studies .

Posen, B. (2003). Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of US Hedgemony. International Security, Vol 28, No1. , pp. 5-46 .

Stratfor. (2019, December). anti-access-area-denial-explained. Retrieved from www.stratfor.com: https://www.stratfor.com/sites/default/files/styles/stratfor_large__s_/public/main/images/anti-access-area-denial-explainer%20(1).jpg?itok=mBf7FOAL

US Department of Defense. (2013, May ). Air Sea Battle: Service Collaboration to Address Anti Access Area Denial Challenges. DoD Periodical.

Supplemental Readings

Cuddington, Jeff. (2015). “Intelligence Operations in Denied Area”, VOL 2, NO 1, (2015): At Home And Abroad: Thinking Through Conflicts and Conundrums, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. ISSN: 2377-1852

Cuddington, Jeff. Jan 2016. Opinion: Need of the hour: New Intelligence Priorities for Anti-Access, Area Denial. accessed Jan 2019 https://www.indrastra.com/2016/01/OPINION-Need-of-the-Hour-A2AD-002-01-2016-0084.html (Accessed Dec, 2019)

DeDrone: Drone Tracker 4.1 Integrated Counter Drone Systems

https://www.dedrone.com/blog/the-8-most-important-innovations-of-dronetracker-4-1

(Accessed Jan 2020)

Defense Matters, (2016) A2/AD Explained in Three Minutes

https://www.defencematters.org/news/a2-ad-explained-three-minutes-vid/1073/

(Accessed Dec 2019)

Erdogan, Aziz. (2018). Russian A2AD Strategy and Its Implications for NATO

https://www.behorizon.org/russian-a2ad-strategy-and-its-implications-for-nato/

(Accessed Dec 2019)

Freier, Nathan (2012) The Emerging Anti-Access/ Area Denial Challenge. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/emerging-anti-accessarea-denial-challenge (Accessed Dec, 2019).

Gholz, Eugene. (2019). What is A2AD and Why Does it Matter to the United States?

Charles Koch Institute.

https://www.charleskochinstitute.org/blog/what-is-a2ad-and-why-does-it-matter-to-the-united-states/ (Accessed Dec 2019)

Russia Missile Threat A2AD (Jan 2017)

https://missilethreat.csis.org/russia-nato-a2ad-environment/

Counter-Hypersonic (Dec 2019)

https://missilethreat.csis.org/mda-reveals-new-hypersonic-defense-program/

Hypersonic Countermeasures (Dec 2019)

https://aviationweek.com/defense/rfp-reveals-main-thrust-us-counter-hypersonic-plan

Barry R. Posen, “Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of U.S. Hegemony,” International Security, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Summer 2003), pp. 5–46.

Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military Power of the People’s Republic of China (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, 2006), pp. 21, 25;

Rem Korteweg and Sophia Besch, No denial: How NATO can deter a creeping Russian threat, 09 February 2016, http://www.cer.org.uk/insights/ (Accessed Dec, 2019)

Simon, Luia. (Jan 2017) Demystifying the A2/AD Buzzhttps://warontherocks.com/2017/01/demystifying-the-a2ad-buzz/ (Accessed Dec, 2019)

U.S. Department of Defense, Air Sea Battle: Service Collaboration to Address Anti-Access and Area Denial Challenges (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, May 2013), http://www.defense .gov/pubs/ASB-ConceptImplementation-Summary-May-2013.pdf;

U.S. Department of Defense, Joint Operational Access Concept (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, January 17, 2012), http://www.defense.gov/pubs/pdfs/joac_jan%202012_signed.pdf.