9 Social Media – The Next Battlefield in Information Warfare [Lonstein]

Student Learning Objectives

This chapter will expose students to the design and deployment of information warfare throughout the annals of the history of war. We will examine concepts such as disinformation, censorship, suppression, consumption, dissemination of information, and their implementation throughout history. Next, we will introduce social media platforms as a ubiquitous form of communication. We will consider whether corporate control of the communication with no constitutional free speech protections, actions of de platforming and censorship, and their impact upon the 2020 United States Presidential election. Finally, we will consider possible methods to address the risks this new reality poses to various stakeholders ranging from individuals to governments, politicians, national security interests, and businesses.

THE HISTORY OF INFORMATION WARFARE

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the definition of “information” is “knowledge obtained from investigation, study, or instruction.” Conversely, the term “disinformation” is “false information deliberately and often covertly spread (as by the planting of rumors) to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.” (Merriam-Webster, 2020) While these definitions are the product of centuries of human experience with the dissemination of information from the days of cave drawings to the written, spoken, and eventually electronically transmitted, the reality is from a perspective of its use in warfare to at least the late 400’s BC and the famed Military Strategist, Sun Tzu. In his treatise “The Art of War,” he postulated “all warfare is deception,” which is, in essence, the seminal discussion of information or disinformation usage as a warfare tool. (Tzu, 1971) Over many centuries, Chinese military treatises include and expand upon this concept. For instance, in Essentials of Sun Tzu’s Art of War and Submarine Operations, a Chinese People’s Liberation Army publication highlighted four information/disinformation concepts espoused by Sun Tzu

- “Show yourself to intimidate the enemy.”

- “Show the false to confuse the enemy.”

- “Create momentum to harass the enemy.”

- “Deceive to obstruct the enemy.” (Shixin, 2002) (Metcalf, 2017)

While ancient civilizations had minimal technology, written, and spoken communication was available and used just as effectively as today. Conflict was also a very significant reality in ancient China, with the conquest of adversaries a necessary and ever-present reality of any empire which sought to survive.

Figure 9.1 (Voice of America, 1957)

According to Major Nathaniel Bastian, in the 18th century, Frederick the Great created a Prussian spy’s system that would gather information from travelers and conduct reconnaissance missions to determine infrastructure, weaponry, and other potential capabilities of its adversaries. He further references propaganda campaigns by Napoleon in the 1800s to publicly portray France as a victim of aggression by adversaries to craft public opinion in neighboring European countries. A few examples of this information warfare included domestic and foreign placards, articles and proclamations, and publications such as the “Bulletin de la Grande Armée” as examples of crafting public opinion, adversarial impressions of Frances military capabilities, and adversary’s responses to the information. (Bastian, 2019)

In the 20th Century, World Wars I and II, as well as many other global conflicts, involved significant implementation of Information warfare whether it be an interruption of information flow via signal jamming, code-cracking, Office of War Information, Office of Strategic Services (now CIA), Voice of America and many more. (Crane, 2019).

Figure 9.2 Social Media Collage (PressureUA/iStock, 2019)

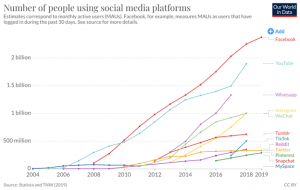

Later in the century, new technologies started to emerge, eventually leading to what is now commonly known as the internet. Names such as Compuserve, Usenet led to the introduction of GENie (General Electric Network for Information Exchange) and Listserv platforms of electronic mail lists, which started to rapidly gain popularity as the price and acceptance of connected technology led to ubiquitous acceptance. As the 1990s came and went, the first “Chatrooms” and employment sites such as the Palace, Friendster and LinkedIn were introduced and surged in popularity. By 2004 Facebook began to commercialize, quickly followed by YouTube, Twitter, and 100’s of others. (McFadden, 2020) Information warfare had evolved from a prehistoric display of cave art to an instant communication method, capable of being instantly and globally disseminated on a peer-to-peer or peer-to-billions basis.

SOCIAL MEDIA TODAY –- INSTANT, PERSONAL, GLOBAL

What is Social Media? According to Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Social Media is “forms of electronic communication (such as websites for social networking and microblogging) through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content (such as videos)” (Merriam-Webster, 2020) For our examination Social Media is not a stand-alone concept or technology; instead, it exists as part of a class of information dissemination referred to as Information and Communications Technology (“ICT”). According to Van Niekerk, Pillay, & Maharaj, ICT is “traditional mass media, online media, including social networks, and communications technologies such as mobile telephones.” (Van Niekwek, 2011)

ICT in the digital age is ubiquitous, affordable, and widely accepted. Even in the most remote and impoverished corners of the globe, the concept of connectivity via computer, smartphone, or other connected technology is a reality for most. Accordingly, the ability to control the access to, quality of, or the accuracy of the information has never been more critical when discussing Information Warfare (“IW”). In a military setting, information warfare is “a class of techniques, including collection, transport, protection, denial, disturbance, and degradation of information, by which one maintains an advantage over one’s adversaries.” (Burns, 1999)

Figure 9.3 “Traditional” Information Warfare Lifecycle (Van Niekwek, 2011)

Dan Kuehl of the National Defense University provided another more succinct definition, who described IW as the “conflict or struggle between two or more groups in the information environment.” (Stupples, 2015)A close examination of Figure 9.3, created in 2011, reveals it is devoid of any substantive reference to Social Media and its role in Information Warfare.

In mid-December 2010, a phenomenon known as the “Arab Spring” began in Tunisia. Essentially the “Arab Spring” consisted of an amalgam of disaffected youth, ethnic minorities, political outcasts, and academia engaging in demonstrations, protests, and ultimately revolutions. They were mainly protesting repression, censorship, lack of economic opportunity, and human rights violations in governments throughout North Africa and the Middle East. This movement was fueled in large part by leveraging the power and scope of mobile social media. The campaign almost immediately spread virally through real-time mobile phone video, tweets, hashtags, Facebook, and other social media tools. The governments of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen were left overthrown in its wake, with numerous others still embroiled in various unrest and even civil war stages. The speed with which the Arab Spring grew is a testament to mobile social media’s power and its ubiquitous instant access. Borders, oceans, and continents were no longer barriers to the transmission and viewing of live, first-hand accounts and media depicting the movement’s rapid growth and its efficacy in toppling governments. (Van Niekwek, 2011)

The power of mobile social media continues to be felt far beyond the Middle East and North Africa. The influence of mobile social media will be felt long after the Middle East and North Africa events. In 2015 the murders of Journalists Allison Parker and Adam Ward were streamed online shortly after they occurred (Shear, 2016). The shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the subsequent protests almost instantly rocketed social media streaming to new heights, not only as a media reporting tool but also as an organization and command and control tool for social information operated by a diverse group of sources ranging from media reporters to citizen journalists, to activists. (Solsman, 2014)

Every corner of the globe began to feel the effects of social media as a tool of information warfare. Viewers saw live violence, political upheaval, and perhaps most tragically, actual death—those who wanted to terrorize orchestrated attacks to stream their final acts of horror to millions watching online. A few examples include the Livestream of a mosque shooting in New Zealand, The Bataclan Nightclub attack in France, and The Parkland High School shooting in Florida.

Figure 9.4 Christchurch New Zealand Mosques Shooter (Tighe, 2019)

What started as an idea to allow people to interact with each other on an easy to use, instant platform with global reach seemed like a great idea when Facebook hit its stride publicly in 2006. Soon Facebook started to understand its technology’s power to collect data regarding its user’s preferences, behaviors, and even darker sides. As did its social media brethren, it discovered that its platforms were excellent marketing tools since they already collected massive amounts of personal data about its users. This acquired knowledge of the users, in turn, allowed the media to market products to the users based upon their profiles and custom design what news and information they see in their information feed further to embed themselves into the lives of billions globally Many believe that today’s Facebook marketing and influence model reflects Edward Bernays’ teachings, who is referred to as the “father of public relations.” (Gunderman, 2015)

In his 1928 book “Propaganda,” Benays wrote:

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, and our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of…. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind.” (Bernays, 1928)

Perhaps no other technology has ever been able to mold the “habits and opinions” at the speed, scale, and individualized sophistication of social media. While other forms of communication such as print, broadcast radio, and television have undoubtedly expanded the ability to reach masses globally, no technology was ever as inexpensive, simple, ubiquitous, and always in the palm of our hands as social media.

Figure 9.5 Social Media Adoption 2004-2019 (Chaffey, 2020)

ENTER DONALD TRUMP – SOCIAL MEDIA DISRUPTOR

By 2015 it was apparent that social media was more than just a popularity contest where users could monetize pet tricks, extreme sports, memes, and other provocative content. With almost four billion users, social media represented entertainment and Donald Trump, a tool of disruption. In the final days of the Barack Obama administration, Donald Trump had become a vocal critic of its policies. While criticism of presidential administrations is nothing new, what was different about Trump was how he communicated his disagreement to the public. Previously critics or would-be presidential candidates would use television and radio appearances, write magazine or newspaper opinion pieces, or appear at events to help drive name recognition and following. Trump was different. On May 4, 2009, Donald Trump, or someone on his behalf, tweeted for the first time: “May 4, 2009, 01:54:25 PM Be sure to tune in and watch Donald Trump on Late Night with David Letterman as he presents the Top Ten List tonight!” (Brown, 2020). In 2009, Trump was the host of his reality show “The Apprentice,” which was a huge success and was likely using Twitter and other Social Media to drive engagement and ratings. In 2011 he started to tack his use of Twitter by criticizing Obama and commenting on political issues of the day. In March of 2011, he began to discuss the prospect of entering the 2012

Presidential race. (Twitter, 2011)

Figure 9.6 Trump 2011 Election Tweet – (Courtesy Twitter @realdonaldtrump)

What followed was nothing short of amazing. Trump decided not to run in 2011 however chose to enter the fray in 2015, which eventually led to his defeat of former First Lady and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in the 2016 United States presidential election. The fact that a political outsider could win the Presidency was not the story. In the past, candidates ranging from Andrew Jackson & Lincoln to Coolidge and Carter positioned themselves as political outsiders. However, most had some degree of governmental or political service on their resume. (WNYC, 2015) Donald Trump indeed was an outsider, a real estate and business mogul, and celebrity; he was even different than former actor Ronald Reagan who ascended to the presidency having first served as Governor of California.

While the broadcast media, who perceived him as a side-show and potential train wreck, during the Republican primary, it was only too quick to give Trump nearly unlimited press in the 2016 race. To that end it was clear that Trump was a social media juggernaut. In a 2016 election post-mortem, Barbara Bickart, Susan Fournier and former New York Times digital, CEO Martin Nisenholtz wrote:

“Big-seed” marketing beats viral. Duncan Watts, a principal researcher at Microsoft Research, has been studying the sociology of networks for decades. His notion of big-seed marketing suggests that a message can spread faster and more systematically if it is “seeded” among many people……….. Trump exploited Watts’s theory at scale. He began with an enormous seedbed: Just before Election Day he had more than 19 million Twitter followers, 18 million Facebook fans, and nearly 5 million followers on Instagram. The broadcast and cable networks — almost unwittingly — amplified Trump’s network capabilities. Every time they reported on a tweet or posting, they effectively seeded the message among millions of viewers, many of whom, in turn, shared these messages. This offline/online complementarity helped Trump double his Twitter following during the campaign. Social and broadcast media work hand in hand, and Trump understood this better than his rivals, gaining by some estimates almost $2 billion in free air time through March 2016.” (Bickart, 2017)

THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION: DISRUPTING THE DISRUPTOR

TAKE AWAY THE MICROPHONE

Stopping Trump from being re-elected would require non-traditional multi-faceted approach designed on the reality of how Trump totally disrupted the electoral process using social media as a primary tool to influence the coverage and behavior of traditional print and broadcast media. Before Trump is even inaugurated, the focus becomes clear, the 2020 United States Presidential Election would be less of a political campaign and more of an information warfare operation than even seen before in United States Politics.

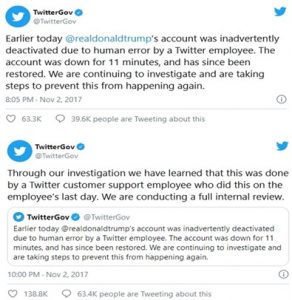

In early November 2017, an “accident” occurred at Twitter when a technology journeyman by the name of Bahtiyar Duysak, a German citizen of Turkish descent was working on a work and study visa at Twitters Trust & Safety department received a “report” of an offensive or otherwise unpopular tweet coming from the account of one @realdonaldtrump. Duysak just happened to have formerly worked at Google and YouTube during the term of his visa and even more curiously this was to be his last day on the job at Twitter.

In an interview with Tech Crunch, shortly after the event when he returned to Germany, Duysak recalled the how the events transpired:

“His last day at Twitter was mostly uneventful, he says. There were many goodbyes, and he worked up until the last hour before his computer access was to be shut off. Near the end of his shift, the fateful alert came in. This is where Trump’s behavior intersects with Duysak’s work life. Someone reported Trump’s account on Duysak’s last day; as a final, throwaway gesture, he put the wheels in motion to deactivate it. Then he closed his computer and left the building.” (Lunden, 2017)

Figure 9.7 TwitterGov on Deactivation of @realdonaldtrump (Courtesy Twitter

The events surrounding the deactivation of the @realdonaldtrump Twitter might be a case of coincidence, even though, according to Statista, it employed almost 4000 people with additional labor coming from independent contractors and employees or vendors. (Statista, 2020) The curious circumstance where the employee happened to be leaving the company and country almost immediately may suggest a trial balloon about censoring Trumps’ social media account. If “likes” are an indicator of reaction, it was undoubtedly positive since over 200,000 people liked the tweets.

CREATE A BOTTLENECK

What is clear is that Trump’s supporters, opponents, and neutrals all recognized his deft implementation of social media as a tool to end-run, traditional media. Opponents became fixated on penetrating Trump’s “Silicon Curtain” of individual communication with many millions of followers and foes alike.

Figure 9.8 Twitter Account @realdonaldtrump December 29, 2020

By the time, the 2020 presidential election season had arrived, Trump’s Twitter account had an incredible 85.5 million followers who could instantly be accessed by his tweets. In contrast, according to the Neilson Company, the average combined viewership of the major broadcast and cable news channels in December 2020 was approximately 26.7 million viewers. (Schneider, 2020) [1]

According to George Lakoff, an emeritus professor at the University of California at Berkeley, and an expert in cognitive science and linguistics, “Trump uses social media as a weapon to control the news cycle. It works like a charm. His tweets are tactical rather than substantive,” “He is as good as it gets [at using social media],” “He is not ranting, that is strategic. Even when he is ranting, it’s strategic. (Buncombe, 2018 )

The disruptive use of technology is nothing new when it comes to the presidency. In May of 1862, Abraham Lincoln, an apparent fan of technology, adopted widespread use of the Telegraph to message Union troops rapidly and efficiently in the field, administration officials, and to the public. In a 2012 opinion piece in the New York Times, Tom Wheeler wrote, “ As he put down the message, Grant (General U.S.) laughed out loud and exclaimed to those around him, “The President has more nerve than any of his advisors.” He was correct, of course, but more important than the message was the media: he held in his hands Lincoln’s revolutionary tool for making sure that neither distance nor intermediaries diffused his leadership.” (Wheeler, 2012) As we will see later on, technology is only useful as long as information transmission is uninterrupted.

“THE SECRET OF WAR” LIES IN THE COMMUNICATIONS”

Napoleon Bonaparte

On August 3, 2020, a group calling itself the Transition Integrity Project issued a report entitled “Preventing a Disrupted Presidential Election and Transition.” The first paragraph reads:

“In June 2020, the Transition Integrity Project (TIP) convened a bipartisan group of over 100 current and former senior government and campaign leaders and other experts in a series of 2020 election crisis scenario planning exercises. The results of all four table-top exercises were alarming. We assess with a high degree of likelihood that November’s elections will be marked by a chaotic legal and political landscape. We also assess that President Trump is likely to contest the result by both legal and extra-legal means, in an attempt to hold onto power. Recent events, including the President’s own unwillingness to commit to abiding by the results of the election, the Attorney General’s embrace of the President’s groundless electoral fraud claims, and the unprecedented deployment of federal agents to put down leftwing protests, underscore the extreme lengths to which President Trump may be willing to go in order to stay in office.” (Transition Integrity Project, 2020)

Almost immediately upon its release, the media gave the report extensive coverage. One of its authors, notably Rosa Brooks, spent the better part of late summer of 2020 discussing her fears of a Rogue Trump losing the 2020 election by a narrow margin and how he might attempt to cling to power. Although carefully crafted as a “bipartisan” group of experts, in reality, the project members and its war-game participants were either democrats, former Bush and Obama Administration officials, or, as the term goes, “Never Trump” republicans. (Gerber, 2020) Former George W. Bush Press Secretary Ari Fleisher was even more concerned about the Transition Integrity Project’s dangerous narrative.

“It strikes me in the era of Trump to be one of the most irresponsible statements I’ve ever heard,” said Fleischer, who was not part of the war games. “I’m perfectly willing, and I do so often, to criticize Donald Trump, but this is pernicious. This is beyond the call. You talk about being divisive. “He called the suggestion that Trump might not accept election results “dangerous.” “Where’s the evidence that this is what Trump is going to do according to his accusers? If the results are clear, the results are clear,” Fleischer said. (Garrison, 2020)

In the age of social media, it has never been clearer that communication is not analogous with or necessarily intended to present facts or truth. Remember, as Bernays wrote, “We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, and our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of…. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind” (Bernays, 1928) Social Media has become the wires used in that process. It is hard to separate truth from fiction online, not to mention whether the content posted emanated from a person, a nation, an organization, or a machine. Suppose the public is unable to self-authenticate the legitimacy and credibility of the author of online content. In that case, it’s undoubtedly going to be a challenge to verify the content they post as accurate or factual. A 2018 editorial on the Investor’s Business Daily website distilled the issue in a fashion that leads back to the only way to determine truth and accuracy is doing it ourselves.

“As the Weekly Standard’s Mark Hemingway explained: “It’s basically a way for a bunch of reporters with no particular expertise to render pseudoscientific judgments on statements from public figures that are obviously argumentative or otherwise unverifiable. Then there’s the matter of them weighing in with thundering certitude — pants on fire! — on complex policy debates they frequently misunderstand.” In the end, the best way to judge the veracity of claims being tossed around is to become better informed about the issues, not contract out that job to people who aren’t necessarily qualified to do for you.” (Investors Business Daily, 2018)

According to Paul Horner, an individual who enriched himself during the 2016 presidential election, Hemingway is correct. We have identified the fake news enemy, and it is us! In an interview with the Washington Post in November 2017, Horner blamed the reader’s laziness and bias for the proliferation of “fake news.” Essentially he accurately believes if someone tells you are right, you are much less likely to fact check them than someone who criticized you.

“Honestly, people are definitely dumber. They just keep passing stuff around. Nobody fact-checks anything anymore — I mean, that’s how Trump got elected. He just said whatever he wanted, and people believed everything, and when the things he said turned out not to be true, people didn’t care because they’d already accepted it. It’s real scary. I’ve never seen anything like it. (Dewey, 2016)

In this environment, it is easier to conduct information warfare using social media (which is now often picked up and repeated by broadcast and print media) to further a narrative throughout society rapidly and at scale. People read it, like the content, believe it, and often spread it.

MARGINALIZE THE MESSAGE – TOXIFICATION OF THE CONSUMER

In October of 2020, the University of California, Berkeley, through its Othering & Belonging Institute, published an online book entitled “Trumpism and its Discontents,” a compilation of content by various authors who drill home the same theme. The forward, written by Professor John A Powell, Director of the Othering & Belonging Institute, contained the following statement: “If the rise of Donald Trump is not grappled with critically, we will not release ourselves from the social corrosion we are all acutely experiencing. The work will be difficult—for many reasons, the least of which is not that it demands a look inward. We must reconsider who we are and who we think we are and think more carefully about how we have tried to answer those questions through the creation and exploitation of other beings instead of by searching for ourselves in relationship with those believed to be the “other.” If we are to together forge a society in which a Trump phenomenon would not be possible, the

conversation must be contextualized on these terms.” (Obasogie, Osagie K, 2020)

The marginalization can be seen in hundreds of examples of literal claims of toxicity of Trump and his followers in the media here are a few:

“NBC Boss: Trump Is Toxic, “Demented” April 13, 2017 Daily Beast (Daily Beast, 2017)

Figure 9.9 Trump Is Toxic – Demented (April 13, 2017 Courtesy Daily Beast)

LET THE BATTLE BEGIN

Caveat: Though this chapter mainly focuses on Twitter because they have, in the author’s opinion, been the most aggressive in taking remedial action for what it deems disinformation, violence, or other content of concern to it, it does not mean that it has taken steps other social media platforms have not. Facebook, Google, and YouTube streaming services, and many others have also engaged in and been subject to both praise and criticism for censoring, warning, or otherwise protecting what they feel is a public interest when it comes to content posted on their platforms.

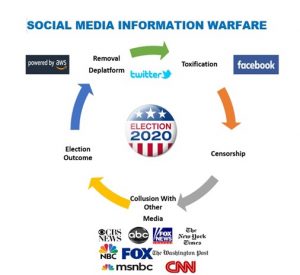

After a tumultuous four years of the Trump presidency, the plan was now clearly crystallizing, given the breadth of the president’s popularity, and following on social media. Leverage his following through a three-step process could be successfully implemented to defeat his reelection. In 2019, Park Advisors prepared a report for the United States Department of State, entitled “Weapons of Mass Distraction: Foreign State-Sponsored Disinformation in the Digital Age.”

Figure 9.10- Social Media Weaponization (Courtesy Daily Times.PK)

Although the report’s focus was on the use of social media disinformation by Foreign States or their proxies, in reality, it laid out the roadmap of how to use the popularity of social media against one of its biggest stars to effectively silence his message.

Spreading false narratives on social media relies on three main premises:

- The medium – the platforms on which disinformation flourishes;

- The message – what is being conveyed through disinformation; and

- The audience – the consumers of such content. (Park Advisors, 2019)

Recall the events of November 2, 2017, when fate struck and a Twitter worker in his last hour of work gets an abuse report for a tweet from the president and disables his Twitter account for 11 minutes. Is a simulated attack replete with penetration testing? Was it even possible to judge reactions to the occurrence to predict actual long-term censorship or disabling of President Trump’s Twitter account? Perhaps. Other operations directed at the Presidents access to social media were ongoing since before his inauguration in 2017. On January 22, 2017, shortly after Trumps inauguration an individual by the name of Yoel Roth Tweeted as follows:

Figure 9.11 Yoel Roth Tweet January 22, 2017 (courtesy Twitter @yoyyoel)

While accusing the President of the United States of being a Nazi is distasteful for the office, it becomes especially problematic when the person tweeting happens to be a part of the same Trust and Safety Team as Bahtiyar Duysak. They “mistakenly” deactivated the President’s Twitter account in November of 2017. In fact, during the 2020 election, Roth was the Head of Site Integrity at Twitter. (LinkedIn, 2020)

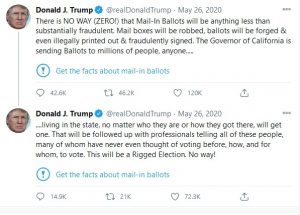

In May of 2020, Twitter escalated its battle against what it called disinformation when for the first time, it placed a warning message on the President’s tweet regarding the issue of fraud and mail-in election ballots.

Figure 9.12 Trump Tweet, May 26, 2020 (Courtesy Twitter @realdonaldtrump)

Three days later, Twitter took a more aggressive stance when it hit a tweet from President Trump behind a warning. Twitter took this unprecedented action because it claimed:

“This tweet violates our policies regarding the glorification of violence based on the historical context of the last line, its connection to violence, and the risk it could inspire similar actions today.

“We’ve taken action in the interest of preventing others from being inspired to commit violent acts but have kept the tweet on Twitter because it is important that the public still be able to see the tweet given its relevance to ongoing matters of public importance.” (TwitterComms, 2020)

Figure 9.13 Trump Tweet, May 29, 2020 (Courtesy Twitter @realdonaldtrump)

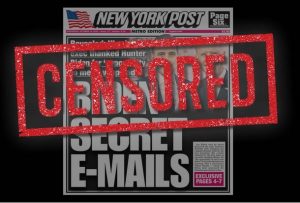

Perhaps the most telling salvo of the censorship war being waged by online and traditional media against the Trump campaign occurred on October 14, 2020, a mere three weeks before the Presidential election. According to the New York Post, it obtained a laptop believed to be owned by and dropped off for repair at a Delaware computer repair shop by Hunter Biden, son of then-candidate Joe Biden. Upon examining the computer, the repairmen found what he felt were critical national security emails. He sent the laptop to the FBI after being unclaimed for many months and being treated as abandoned. Not hearing back from the FBI and knowing the contents of the computer were of critical national interest to the nation in light of ties between Hunter Biden and the Ukrainian, Russian and Chinese governments and businesses, the repairmen provided a copy of the hard drive he had made to presidential attorney Rudolph Giuliani.[2]

Giuliani and the Trump campaign then provided the hard drive image to the New York Post for confirmation and reporting. When the New York Post reported the story, it was big news. Almost immediately, the Posts’ Twitter account was banned, and Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube restricted sharing of the story, and broadcast media largely ignored the story.

Figure 9.14 New York Post October 14, 2020 (Courtesy NY Post)

Almost immediately, the Trump campaign and many print and online media outlets protested this unprecedented act of censorship, and Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s CEO, had to eat crow and admit that Twitter’s “actions” surrounding the New York Post article “were not great.” (Twitter, @jack Twitter, 2020)

Figure 9.16 Twitter Apology New York Post October 14, 2020 (Courtesy Twitter)

Censorship was not the only weapon in the Information Warfare campaign during election 2020. In 2020 the term “disinformation” became widely used to suggest social media or online content contained much falsehood which, relates to many claims regarding the 2016 Presidential Election. See; Russia’s Pillars of Disinformation and Propaganda Report.. (United States Department of State, 2020) Case in point, in the early summer of 2020, the Biden-Harris team launched an online pressure campaign targeting Facebook claiming,

“Facebook…. It continues to allow Donald Trump to say anything — and to pay to ensure that his wild claims reach millions of voters. SuperPAC’s and other dark money groups are following his example. Trump and his allies have used Facebook to spread fear and misleading information about voting, attempting to compromise the means of holding power to account: our voices and our ballot boxes.” (Biden for President, 2020)

This tactic relied upon classifying the message and the messenger to drive a narrative to the masses that Trump’s social media statement was, in fact, disinformation. This tactic’s objective was to create an assumption that all Trump posting was disinformation and, therefore, untrustworthy. After the election in January 2021, citing a violent protest at the United States Capitol, both Facebook and Twitter permanently banned the social media accounts of Donald Trump. Mission accomplished. . (Twitter, 2021) (Zuckerberg, 2021)

HOW WILL LAW, POLICY AND MARKETS REACT?

As of January 1, 2021, Joseph Biden has been declared the 2020 US Presidential election winner. Unfortunately, the issues we have examined in this chapter have led many Trump supporters to believe that big technology companies, broadcast, print, and social media placed a hand on the scales of fairness. Trump and his supporters claim that electronic voting technology, mail-in ballots, and early voting created a “perfect storm” of election fraud.

They also claim sizeable financial assistance from social media companies and their executives negatively impacted his campaign in six “battleground” states where the margins of victory were very tight. To date, none of these claims have been proven in or accepted by a Court of Law. (Sheck, 2020)

Many on both sides of the aisle suggest that social media companies enjoy unwarranted protection from liability for their actions under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. (Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, 2020) While reform of this law may bring some relief to those who claim injury caused by social media company activity, it certainly is under pitched debate in Congress. Still, it would fail to address social media companies outside the United States.

Others say there needs to be legislation enacted which affords individual and companies the same protections afforded them under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. (United States Courts, 2020). By analogy, this type of oversight finds justification under the same theories which allow Public utility regulation. In 2018 Professor Anjana Susarla of Michigan State University was quoted as saying:

“It is both an open platform for free expression of diverse viewpoints and a public utility on which huge numbers of people — and democracy itself — rely for accurate information……….. It’s true that overregulation does run the risk of censorship and limiting free expression. But the dangers of too little regulation are already clear, in the toxic hate, fake news and intentionally misleading propaganda proliferating online and poisoning democracy. In my view, taking no action is no longer an option.” (Susarla, 2018)

Recently a Justice Minister in Poland introduced legislation that would impose hefty fines on social media companies who wrongfully censor legal speech, (PolandIn, 2020) and Senator Mike Lee of Utah introduced the PROMISE ACT (Promoting Responsibility Over Moderation In the Social Media Environment Act). (Davidson, 2020) While each of these regulatory adjustments may hold promise, in reality, in the heat of a campaign or while running a private business, being censored by social media can be disastrous, and merely waiting for new legislation or filing lawsuits may not prevent irreparable harm.

The new reality is that social media censorship, primarily based upon opaque policies of conduct and arbitrary enforcement standards, amounts to the equivalent of a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack.

The internet company Cloudflare defines a DDoS attack as:

“A distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack is a malicious attempt to disrupt the normal traffic of a targeted server, service or network by overwhelming the target or its surrounding infrastructure with a flood of Internet traffic. DDoS attacks achieve effectiveness by utilizing multiple compromised computer systems as sources of attack traffic. Exploited machines can include computers and other networked resources such as IoT devices. From a high level, a DDoS attack is like an unexpected traffic jam clogging up the highway, preventing regular traffic from arriving at its destination.” (Cloudflare, Inc., 2020)

When it comes to social media and its 4 billion users, simply censoring information or de-platforming individual posters or users can have the same effect as a DDoS attack. When conducted independently or in coordination with the most significant social media networks, it creates de facto censorship of dissenting voices.

Internet libertarian and free speech advocate John Gilmore once wrote, “The Internet interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.” In 2020 Brian Krebs, a noted cybersecurity expert, found his website taken offline when a massive DDoS attacked targeted his domain. His internet service provider informed him that the attack compromised their systems and customers, and therefore the website must remove its network. Krebs described the situation this way:

“Censorship can in fact route around the Internet.” The Internet can’t route around censorship when the censorship is all-pervasive and armed with, for all practical purposes, near-infinite reach, and capacity. I call this rather unwelcome and hostile development the “The

Democratization of Censorship.”

Figure 9.15 the Democratization of Censorship (Courtesy Brian Krebs)

What Krebs described in 2016 was eerily similar to what occurred to the Trump reelection campaign in 2020. The difference was that censorship and de-platforming were at the request of an internet service provider or Content Distribution Network (CDN); it was being waged actively and passively by social, broadcast, and print media companies.

As you can see, there are many potential risks to using social media to conduct a political campaign, run a business, and conduct government operations. We now turn to countermeasures, risk mitigation, and related strategies to address this growing challenge to many people and entities maintaining an online or social media presence.

COUNTER-CENSORSHIP- SOCIAL MEDIA RESILIENCY STRATAGIES AND TECHNOLOGY

P.A.C.E., what is it and why does it matter?

PACE communications planning is a military-inspired concept designed to ensure a robust ability to effectively communicate during times when the unexpected happens so that panic, fear, and confusion do not compromise an organization’s operational readiness. According to the Puget Sound Healthcare Emergency Communications Systems;

“Developing comprehensive PACE plans will not ensure perfect communications in a disaster but helps to clear some of the fog and friction found in every emergency situation. Developing comprehensive PACE plans will not ensure perfect communications in a disaster but helps to clear some of the fog and friction found in every emergency situation.” (Puget Sound Healthcare Communications Systems, 2018) citing (Ryan, 2013)

- Primary: The main form of communication.

- Alternate: If the primary fails, this is your secondary form of communication

- Contingency: Tertiary method of communication

- Emergency: If all else fails, this is the worst-case option. (Fire Watch Solutions, 2018)

The implications of a loss of communications are widely known, whether it be a military operation where command and control are lost, and aircraft are losing radio contact with ground controllers and other aircraft, or merely finding your internet service down. The first two are potentially fatal, the third a nuisance, but all three demonstrate without communication, it is challenging to function effectively in a data-driven world.

Figure 9.17 PACE Planning (Courtesy Chris Littlestone, Life is a Special Operation)

Cyberspace makes the challenge of communication protection even more difficult. To have a practical strategy, students must consider some of the lessons learned in primary information security education, particularly the CIA Triangle. The CIA Triangle, in its traditional form, has three legs, Integrity, Availability & Confidentiality.

Figure 9.18 CIA Triangle (Courtesy Infrosecuritybuzz.com)

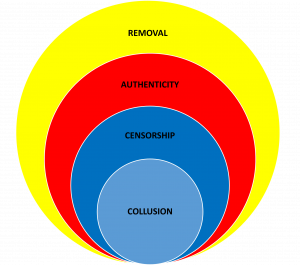

Students will undoubtedly face challenges relating to the successes and failures of the 2020 Presidential election for years to come. As we have seen in the earlier parts of the chapter, it is relatively easy to weaponize social media in multiple ways and different combinations depending upon the objective.

Figure 9.19 Social Media RACC Threat Matrix (Courtesy VFT Solutions, Inc.)

Removal from a social media platform can have a devastatingly significant effect upon a campaign, a business, or an operation that leverages one platform far over the others. The result can be an imbalance where the removal from the platform of choice, in 2020 for President Trump it was Twitter can result in multiple hardships from merely communicating with supporters to redirect them to alternative media in time to avoid significant disruption and confusion.

Toxification is a method to make all content posted online by a source to be suspicious and assumed to be untrue. The tactic can be more effective and less noticeable to the audience than outright censorship or removal from a platform because it is very passive and operates like a subliminal message. As the Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels is reputed to have said;

“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it. The lie can be maintained only for such time as the State can shield the people from the political, economic and/or military consequences of the lie. It thus becomes vitally important for the State to use all of its powers to repress dissent, for the truth is the mortal enemy of the lie, and thus by extension, the truth is the greatest enemy of the State.” (Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team, 2010)

On the other hand, disinformation posted online can have equally significant value since it can create damaging narratives that are difficult if not impossible to recover. A perfect example of this would be the 2017 “Dossier,” which allegedly detailed collusion between Russia and the 2016 Trump campaign. This narrative persisted through the entire first four years of the Trump presidency and though proven demonstrable false, still is used as a useful tool to fuel false narratives.[5]

Censorship on social media is a complex issue. The platforms claim to be the sole judges of the content posted on their media since they are private businesses. Usually, the platform will tailor its Terms of Service to allow for them to decide what can and what cannot be posted and to change the rules without notice. As we discussed earlier, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, at least in the United States, allows them to do so with impunity.

Collusion, either overtly or de facto, has proven to be a devastatingly effective tool. When one social media platform uses its “Fact Checkers” to support content censorship, the adage strength in numbers applies. While there are many unknowns about Election 2020, for now the following Social Media Information Warfare Cycle (Figure 9.20) appears accurate.

Figure 9.20 Social Media Information Warfare Lifecycle

Suffice it to say that the challenges presented by social media are varied and will likely impact most student’s careers in one way or another. There are no definitive answers; however, to help address the challenge, the following steps may serve as Best Practices to minimize, if not secure online operations from social media risks mentioned above with impunity

- Rapidly identify trending content that may be relevant to a particular stakeholder’s interest. Understand that push notifications can make posts go viral in seconds, and live social media streams to go from one to over one million viewers in a minute. As Churchill once said, “There are a terrible lot of lies going about the world, and the worst of it is that half of them are true.” (British Broadcasting Company, 2015)

- Develop overlapping, multiple social media accounts on as many platforms as possible. When it comes to social media live streaming, this task has become much simpler with stream casting technology. A single live or recorded stream can be simultaneously broadcast on multiple platforms, decentralizing a portion of RACC risk. Some technologies which can easily support this function include restream.io, Camera Fi, and melonapp, to name a few. See Figure 9.21.

Figure 9.21 (Courtesy restream.io)

- Standalone mirror platform. A standalone mirror platform is simply a proprietary asset owned by the stakeholder, which has all the features of a traditional social media platform. The difference is that content is curated, controlled, and owned by the stakeholder. Inexpensive live streaming and video on demand technology are now extremely affordable and straightforward to rapidly integrate into a website. This standalone should have a URL listed in the description of all social media accounts operated by the stakeholder as well as be reachable through SMS “text to” technology (i.e., Text CENSOR to 555221)

- Employ live message insertion technology. Live message insertion technology is a patented process whereby all social media is scraped in real-time using various search and recognition technologies to identify relevant content. After that, an automated or manual message is inserted on multiple social media streams simultaneously. This process redirects viewers away from disinformation to legitimate and accurate content. And they were coupled with a reverse distribution; this countermeasure can be deployed in a remote, distributed fashion globally, override and compete with other individuals, or collective censorship attacks. See Figure 9.22.

Figure 9.22 Live Social Media Message Insertion (Courtesy VFT Solutions, Inc.)[4]

CONCLUSIONS

Technology changes at a rapid pace; social media technology seems to change at the speed of light. This chapter’s content exposes students to a brief overview of the scope and breadth of how social media has changed and disrupted our lives. What may true today may be outdated or incorrect one hour from now; the key is for students to understand the rapidly shifting landscape and how such shift can impact personal inconvenience or benefit to global change or conflict. Technologists, security specialists, and other professionals would do well to stay abreast of this emergent technology, currently in individual use by over one-half of the world population.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER

- You are the global marketing president for Tesla Automobiles. As a popular automobile brand in the age of technology, green energy, and social awareness you learn the companies Chairman Elon Musk has made a politically unpopular statement regarding his fondness for eating foie gras. In response PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) calls for a boycott of all Tesla products as well as a delisting and censorship of all content and advertisements on social media. What steps would you take in order to mitigate risk to your global business, respond to the story, maintain social media contact with your loyal customer base? What steps would you take to protect if other nations who were pro-duck decided to block all social media companies doing business in their nation which allowed pro foie gras content to be posted?

- As part of your position as social media director of the local mayoral campaign, you are told to present a plan to create social media messaging to make your candidate look as if he supports gun control while painting the opponent as a supporter of full concealed carry weapons rights in public places including schools. How would you address the opponent’s ten thousand social media followers? Would you post on his social media platforms? How would you fact check the information you intended to post? Would you post content that could not be 100% verified as accurate? What contingency plans would you create in case as a result of your postings, your candidate was de-platformed across social media?

References

@realdonaldtrump. (2020, May 26). Twitter @realdonaldtrump. Retrieved from Twitter: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1265255835124539392

Agrawal, G. (2019, January 19). CIA Triad in Details… Looks Simple but Actually Complex. Retrieved from MRCISSP: https://mrcissp.com/2019/01/09/cia-triad-in-details-looks-simple-but-actually-complex/

Bastian, M. N. (2019, Fall). Information Warfare and Its 18th and 19th Century Roots. FALL 2019|5 THE CYBER DEFENSE REVIEW , 31-38.

Bernays, E. (1928). Propaganda. Brooklyn: IG Publishing.

Bickart, B. F. (2017, March 1). What Trump Understands About Using Social Media to Drive Attention. Retrieved from Harvard Business Review: https://hbr.org/2017/03/what-trump-understands-about-using-social-media-to-drive-attention

British Broadcasting Company. (2015, April 9). 50 Sir Winston Churchill Quotes to Live By. Retrieved from BBC: https://www.bbcamerica.com/blogs/50-churchill-quotes–49128

Brown, B. (2020, December 22). Trump Twitter Archive. Retrieved from The Trump Archive: https://www.thetrumparchive.com/?results=1

Buncombe, A. (2018 , January 17). Donald Trump one year on: How the Twitter President changed social media and the country’s top office. Retrieved from The Independent: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/the-twitter-president-how-potus-changed-social-media-and-the-presidency-a8164161.html

Burns, M. (1999). Information Warfare: What and How? Retrieved from Carnegie Mellon School of Computer Science: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~burnsm/InfoWarfare.html

Chaffey, D. (2020, August 3). Global social media research summary August 2020. Retrieved from Smart Insights: https://www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-strategy/new-global-social-media-research/

Cloudflare, Inc. (2020, December 27). What is a DDoS Attack? Retrieved from Cloudflare: https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/ddos/what-is-a-ddos-attack/

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. (2020, December 30). Protection for private blocking and screening of offensive material. Retrieved from Legal Information Institute: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230

Crane, C. (2019). A Return to Information Warfare. Carlisle : Historical Services Division, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center.

Daily Beast. (2017, April 13). NBC Boss: Trump Is ‘Toxic,’ ‘Demented’. Retrieved from Daily Beast: https://www.thedailybeast.com/cheats/2016/08/16/nbc-boss-trump-is-toxic-pompous

Davidson, L. (2020, December 9). en. Mike Lee pushes bill to punish Facebook, Twitter if they show anti-conservative bias. Salt Lake Tribune.

Dewey, C. (2016, November 17). Facebook fake-news writer: ‘I think Donald Trump is in the White House because of me’. Retrieved from The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2016/11/17/facebook-fake-news-writer-i-think-donald-trump-is-in-the-white-house-because-of-me/

Fire Watch Solutions. (2018, July 6). Emergency Communications: What is a PACE Plan? Retrieved from Medium: https://medium.com/firewatch-solutions/emergency-communications-what-is-a-pace-plan-694f14250bd2

Garrison, J. (2020, August 6). Experts held ‘war games’ on the Trump vs. Biden election. Their finding? Brace for a mess. Retrieved from USA Today: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/08/06/election-2020-war-games-trump-vs-biden-race-show-risk-chaos/5526553002/

Gerber, S. D. (2020, September 22). A president has the constitutional right to contest results of election. Retrieved from The Hill: https://thehill.com/opinion/white-house/517519-a-president-has-the-constitutional-right-to-contest-results-of-election

Gunderman, r. (2015, July 9). The manipulation of the American mind: Edward Bernays and the birth of public relations. Retrieved from The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/the-manipulation-of-the-american-mind-edward-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-44393

Hannigan, D. (2020, October 29). America at Large: Golfers guilty of legitimizing Trump’s toxic regime. Retrieved from The Irish Times: https://www.irishtimes.com/sport/golf/america-at-large-golfers-guilty-of-legitimising-trump-s-toxic-regime-1.4393196

Hannigan, D. (2020, October 2020). America at Large: Golfers guilty of legitimizing Trump’s toxic regime. Retrieved from The Irish Times: https://www.irishtimes.com/sport/golf/america-at-large-golfers-guilty-of-legitimising-trump-s-toxic-regime-1.4393196

Investors Business Daily. (2018, August 2). Who Is Fact Checking The Fact Checkers? . Retrieved from Ivestors Business Daily: https://www.investors.com/politics/editorials/fact-checkers-big-media/

Krebs, Brian. (2016, September 25). The Democratization of Censorship. Retrieved from Krebs on Security: https://krebsonsecurity.com/2016/09/the-democratization-of-censorship/

LinkedIn. (2020, December 31). Yoel Roth – LinkedIn. Retrieved from LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/yoelroth/

Littletone, C. (2020, December 30). Life is a Special Operation. Retrieved from YouTube Life Is A Special Operation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52W-aoichfw

Lunden, I. H. (2017, November 29). Meet the man who deactivated Trump’s Twitter account. Retrieved from Tech Crunch: https://techcrunch.com/2017/11/29/meet-the-man-who-deactivated-trumps-twitter-account/

McFadden, C. (2020, July 2). A Chronological History of Social Media. Retrieved from Interesting Engineering: https://interestingengineering.com/a-chronological-history-of-social-media

Merriam-Webster. (2020, December 16). Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved from Merriam-Webster.com: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary

Metcalf, M. (2017, February). Deception Is the Chinese Way of War. United States Naval Institute Magazine.

Middleton, C. (2018). SAP launches ethical A.I. guidelines, expert advisory panel. Retrieved from internetofbusiness.com: Middleton, C. (2018). SAP launches ethical A.I. guidelines, expert advisory panel. Retrieved from https://internetofbusiness.com/sap-publishes-ethical-guidelines-for-a-i-forms-expert-advisory-panel/

New York Post. (2020, October 14). Twitter, Facebook censor Post over Hunter Biden exposé. Retrieved from New York Post: https://nypost.com/2020/10/14/facebook-twitter-block-the-post-from-posting/

Obasogie, Osagie K. (2020). Trumpism and its Discontents. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press.

Park Advisors. (2019). MARCH 2019WEAPONS OF MASS DISTRACTION: Foreign State-Sponsored Disinformation in the Digital Age. Washington, DC: Park Advisors.

PolandIn. (2020, December 18). Justice Minister announces online freedom of speech bill. Retrieved from PolandIn: https://polandin.com/51388314/justice-minister-announces-online-freedom-of-speech-bill

PressureUA/iStock. (2019, September 19). Social Media Apps Logotypes Printed on a Cubes stock photo. Retrieved from iStock.com: https://www.istockphoto.com/photo/social-media-apps-logotypes-printed-on-a-cubes-gm1173494837-325964650

Puget Sound Healthcare Communications Systems. (2018, December 30). PACE for Healthcare Emergency Communications Planning. Retrieved from PUSHECS Council: https://pushecs.org/resources/ideas_concepts/pace/

Raza, Z. (2020, July 18). Rhizomatic speed of Social media evolves to warfare tools. Retrieved from Daily Times: https://dailytimes.com.pk/642477/rhizomatic-speed-of-social-media-evolves-to-warfare-tools/

Restream. (2021, January 1). Restream. Retrieved from Restream: https://restream.io/

Ryan, M. M. (2013, Summer). A SHORT NOTE ON PACE PLANS. Retrieved from Infantry Magazine: https://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2013/Jul-Sep/pdfs/Ryan.pdf

Schneider, M. (2020, December 28). Year in Review: Most-Watched Television Networks — Ranking 2020’s Winners and Losers. Retrieved from Variety: https://variety.com/2020/tv/news/network-ratings-2020-top-channels-fox-news-cnn-msnbc-cbs-1234866801/

Shear, M. e. (2016, August 26). Ex-Broadcaster Kills 2 on Air in Virginia Shooting; Takes Own Life. Retrieved from New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/27/us/wdbj7-virginia-journalists-shot-during-live-broadcast.html

Sheck, T. H. (2020, December 8). How Private Money From Facebook’s CEO Saved The 2020 Election. Retrieved from NPR: https://www.npr.org/2020/12/08/943242106/how-private-money-from-facebooks-ceo-saved-the-2020-election

Shixin, G. (2002). Essentials of Sun Zu’s Art of War and Submarine Operations. Beijing: Military Science Press.

Solsman, J. S. (2014, August 26). How Ferguson brought live streams into the mainstream. Retrieved from CNET: https://www.cnet.com/news/how-ferguson-brought-live-streams-into-the-mainstream/

Statista. (2020, December 29). Number of Twitter employees from 2008 to 2019. Retrieved from Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272140/employees-of-twitter/#:~:text=The%20statistic%20provides%20the%20number%20of%20employees%20of,and%20of%20a%20white%20ethnicity%20with%2043.5%20percent.

Stupples, D. (2015, November 26). The next war will be an information war, and we’re not ready for it . London, United Kingdom.

Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. (2020, December 29). Retrieved from https://suntzusaid.com/: https://suntzusaid.com/book/10/3/

Susarla, A. (2018, August 17). Facebook shifting from open platform to public utility. Retrieved from UPI: https://www.upi.com/Top_News/Voices/2018/08/17/Facebook-shifting-from-open-platform-to-public-utility/1721534507642/

Tighe, M. S. (2019, March 15). Facebook, YouTube face ire over live streaming of Christchurch attack . Retrieved from Business Standard: https://www.business-standard.com/article/international/facebook-youtube-face-ire-over-live-streaming-of-christchurch-attack-119031500493_1.html

Transition Integrity Project. (2020). Preventing a Disrupted Presidential Election and Transition. Washington, DC: Transition Integrity Project.

Twitter. (2011, March 16). Twitter. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/48100699418005504?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E48100699418005504%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.thetrumparchive.com%2F%3Fresults%3D1

Twitter. (2017, January 22). @yoyoel. Retrieved from Twitter: https://twitter.com/yoyoel/status/823312771416588288

Twitter, @. (2020, October 14). @jack Twitter. Retrieved from Twitter: https://twitter.com/jack/status/1316528193621327876

Twitter, @. (2020, October 14). @jack Twitter. Retrieved from Twitter: https://twitter.com/jack/status/1316528193621327876

TwitterComms. (2020, May 29). Twitter@twittercomms. Retrieved from Twitter: https://twitter.com/twittercomms/status/1266267447838949378?lang=en

Tzu, S. (1971). The Art of War. Translated by Samuel B. Griffith. New York. New York: Oxford University Press.

United States Courts. (2020, December 29). What Does Free Speech Mean? Retrieved from United States Court’s: https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/what-does

Van Niekwek, P. &. (2011). Analyzing the Role of ICTs in the Tunisian and Egyptian Unrest. International Journal of Communication, 1406.

VFT Solutions, Inc. (2020). VFT Counter Social Media Censorship Strategies. Ellenville, NY: VFT Solutions, Inc.

Voice of America. (1957, February 25). President Eisenhower Speaking at VOA. Washington, DC, USA.

Weaver, C. (2020, October 9). ‘To be near Trump is toxic’: Covid-19, chaos and the election. Retrieved from Financial Times: https://www.ft.com/content/f2b6873c-b274-4f25-b319-847ea5303bf2

Wheeler, T. (2012, May 24). The First Wired President. New York Times.

WNYC, S. (2015). A Brief History Of The Political “Outsider” [Recorded by J. Brenneman]. New York, New York, United States of America.

[1] Citing SOURCE: NIELSEN, NPM (12/30/2019.12/06/2020, LIVE+7 AND 12/07/2020-12/22/2020, LIVE+SD VS. 12/31/2018-12/08/2019, LIVE+7 AND 12/09/2019.12/24/2019, LIVE+SD) MON-SAT 8PM-11PM/SUN 7PM-11PM, AD-SUPPORTED AND PREMIUM PAY NETWORKS. NAT GEO MUNDO BASED ON NPM-H. RANKED BY 2020 YEAR-TO-DATE.

[2] To date the author is unaware of any denial by the Biden family or campaign that the laptop at issue was in fact owned & dropped off by Hunter Biden or that any of the reported contents of its hard drive were not correct.

[3] https://apnews.com/article/7b7d698b9a660997f5e755d92b775d98 Robert Mueller’s report debunks Russia dossier

[4] In the interest of full transparency, VFT Solutions is the owner of patented social media scraping and messaging technologies and patents. Author Wayne Lonstein is a principal of VFT Solutions

[5] https://apnews.com/article/7b7d698b9a660997f5e755d92b775d98 Robert Mueller’s report debunks Russia dossier