2 Writing

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- How does viewing writing as a process influence writing instruction?

- How does using the 6 +1 Traits of writing influence instruction and assessment of writing?

- How do teachers teach writing at the primary level?

Section 1 – Writing as a Process

Why do you write? As a college student, the typical answer is “because we have to.” But, dig a little deeper.

We write to describe feelings; to express information; to work out problems; to persuade people; to connect to others; to remember; to learn – and the list goes on. We create meaning through writing and the writing conveys it to others.

This magic and passion is what our students need to discover through their own writing and their own writing identities.

And to do that, teachers need to be writers. You need to see yourself as a writer and open your writing process to your children.

For many people, this is a paradigm shift. It is likely that much of your writing life has been filled with assignments and topics assigned to you by others with limited choice in form, style, structure, topic, or audience. You might not feel like you are a writer. But, the only requirement of being a writer is to write.

In this course, you will be asked to keep a writer’s notebook to complete the mini-lessons that your peers present. It will give you a taste of how teachers create a supportive writing environment, but we encourage you to explore your own “writerly life” (Calkins, 1994) through your own writing outside of class.

In addition, although this chapter focuses on the traditional medium of words, we’d like to also consider the process of composing in other mediums such as video, images, and music. Artists in these mediums use a composing process that is similar to the writing process.

The Process of Writing

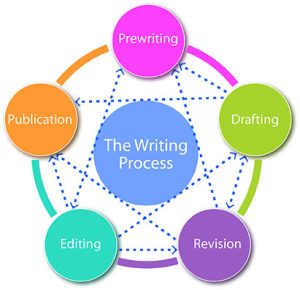

Although there is no one right way to write, we do know that writing is a process, not just the product. The process needs to be adjusted based on the genre and purpose of the writing, but there are five typical tasks involve in a piece of writing/representing:

-

- Prewriting

- Draft

- Revise

- Edit

- Publish

Like the bullet points previously, the writing process is often presented as a linear process, however, it rarely is a clear, smooth linear process as the image above indicates. Writers often move back and forth between steps. However, for ease of explanation, we will discuss each stage as an individual step.

Pre-Writing

Pre-writing is the stage that writers use to gather ideas. There are a variety of tools writers use to gather and expand on their ideas before drafting, a few are described below:

-

- Writing Territories – Nancie Atwell introduced writing territories to her students to help them document the topics, genres, and events in their lives for future writing. Basically, it is a list of words or phrases generated by students to remind themselves of the areas available to them for writing.

Writing Territories Anchor Chart

- Writing Territories – Nancie Atwell introduced writing territories to her students to help them document the topics, genres, and events in their lives for future writing. Basically, it is a list of words or phrases generated by students to remind themselves of the areas available to them for writing.

-

- Heart Maps – Georgie Heard helped her students gather ideas for writing through Heart Maps. Starting in the center of a blank heart template, students write words or pictures that represent the important people, places, things, or events in their lives.

-

- Life Graph – Students in Linda Rief’s class created Life Graphs selecting important events in their lives to represent through an icon or small picture and graphing them on a negative to positive scale on a typical graph.

A Middle School Student Life Graph

- Life Graph – Students in Linda Rief’s class created Life Graphs selecting important events in their lives to represent through an icon or small picture and graphing them on a negative to positive scale on a typical graph.

-

- Graphic Organizers – There are a variety of graphic organizers that can support children in gathering ideas for writing such as basic outlines, story maps, concept webs, flow charts, or hamburger organizers.

Sources for Graphic Organizers.

- Discussion – Often providing time for students to talk about topics before writing improves the quality and depth of writing. The use of Think/Pair/Share or Turn and Talk can help students clarify their thinking before drafting.

- Graphic Organizers – There are a variety of graphic organizers that can support children in gathering ideas for writing such as basic outlines, story maps, concept webs, flow charts, or hamburger organizers.

Drafting

Using the pre-writing notes, a writer begins drafting by organizing those notes and considering the purpose and genre of the writing.

For many writers, the blank page can be scary. Teachers can provide support in starting through the use of sentence frames; allowing students to write on notecards or sticky notes rather than regular paper; or providing mini-lessons on introductions, leads, topic sentences, developing characters, etc.

The most important part of the drafting stage is to get words on paper. For reluctant writers, teachers will need to provide a lot of emotional support.

Revising

Although used interchangeably, revision and editing are two different processes. Revision focuses on the “big picture” of the writing – Does it make sense? What needs to be clarified, deleted, or re-ordered?

At the elementary level, teachers can provide rubrics, checklists, and other strategies to help writers revise their own work, or work with a peer to revise.

Editing

Editing is the process of proofreading for the conventions of English. Teachers use a variety of acronyms including:

- ARMS – add, remove, move, and substitute;

- GUMS – grammar, usage, mechanics, and spelling;

- CUPS – capital letters, understanding, punctuation, and spelling;

- CHIMPS – capitalization, handwriting, indents, makes sense, punctuation, and spelling.

Links and Printables for Revising and Editing

Publishing

Not every piece of writing needs to be published, but to create an identity of a writer, children do need to have an audience. Publication can take a variety of forms – an author’s chair, paper on the bulletin board, class book, or an online website.

Section 2 – The 6+ 1 Traits of Writing

Writing is a complex activity and to support writers, teachers can use the language of 6+1 Traits of writing to break down the components of writing into manageable parts.

Developed by Ruth Culham, the six traits of writing is not a curriculum or program, but a way of talking about writing – which can lead to more focused lessons and assessments. Based on years of research on the characteristics of effective writing across genres, six traits were originally identified and the +1, or seventh trait of presentation, was added to address the needs of a multimedia world

Ideas – The idea of a piece of writing is the main message. The genre and purpose of the writing influence what the main idea will be. Writing that is strong in the trait of Ideas will have a clear message or theme, details that support the message, and the main message is interesting and original.

Organization – Effective writing has a clear organizational structure that will depend on the genre and purpose. Some typical patterns of organization include: chronological order; compare/contrast; spacial; or problem/solution. In English, story structures typically have a beginning, middle, and end.

Voice – The personality of the writer that comes through the writing is the trait of Voice. It is developed through specific word choices, phrasing, passion for the topic, and tone.

Word Choice – Rich, vivid, and specific word choices provide interest and imagery in the writing. The use of figurative language enhances narrative and descriptive writing. The precision of the language is more important than the uniqueness of the vocabulary.

Sentence Fluency – The sound of the words when read aloud (or in the reader’s head) needs to flow. Rhythm, word choices, phrase patterns, and paragraphing all contribute to the fluency of the writing.

Conventions – For readers to understand a piece of writing, it needs to conform to the conventions of English. Correct spelling, grammar, punctuation, etc. is important to allow the ideas to shine.

Presentation – The presentation of writing includes both visual and textual elements. At the very basic level, the writing needs to be readable. However, other elements can enhance the reader’s experience, such as the choice of font, use of white space, graphics, borders, and overall appearance. When writing is taken into multimedia, the additional elements of movement and sound need to be considered.

How do teachers use 6+1 Traits?

For instruction – Using the Gradual Release of Responsibility model, mini-lessons based on the 6 +1 Traits provide opportunities for children to work with mentor texts that illustrate the trait; observe a model of using the trait by the teacher; and practice the trait in their own writing. An important part of understanding the traits is providing multiple models of the trait and naming the writer’s craft in using it.

For assessment – With support, children can use checklists or rubrics to assess their own writing or work with a peer to revise their writing. Teachers can also use these tools to assess children’s writing.

Some sources for lesson plans on the 6+1 Traits of Writing:

- A Collection of Activities to Teach Writing According to the Six-Trait Framework

- Twinkle – What are the 6 Traits of Writing?

- Education Northwest Resources

Section 3 – Writing Instruction

As mentioned previously, to become a writer, children must write, and their teachers need to be writing with and beside them.

When we think about writing, there are three main forms of writing:

-

- Narrative – Typical when a story is in English, the narrative structure includes a beginning, middle and, end – frequently identified with a plot graph that builds up to a climax with a resolution.

- Informative – Sometimes called expository writing, the purpose of informative writing is to educate the reader about a topic. Genres include: biography, reports,

- Argumentative – The purpose of argumentative writing is to persuade the reader to believe the writer’s claim through the use of evidence.

There are three key areas that develop a culture of writing in a classroom: a supportive environment, intentional writing instruction, and writing assessment (Gambrell & Morrow, 2015).

Developing a Supportive Writing Environment

A supportive writing environments include an awareness of the physical and social aspects of the classroom, along with individual children’s needs.

The physical characteristics of a print-rich classroom include easy access to a variety of traditional and digital tools; resources for viewing words; a large classroom library; and physical spaces that encourage involvement in mini-lessons, peer revision, and conferring.

-

- Access to a variety of tools – This includes different kinds of paper, writing utensils (pen, marker, crayon), writing mediums (paper, whiteboard, computer), and support tools (dictionaries, word walls)

- Resources for viewing words – Especially for early writers, resources for viewing words prompt their writing. Environmental print, labeled equipment (desk, trash, map), and word walls provide opportunities for children to see the words they might select for their own writing.

- Classroom library – Reading informs writing (and vice versa), therefore a well-stocked library is an essential tool for writers. Providing mini-lessons using mentor texts that illustrate the writer’s craft and then placing the title in the library allows children to revisit mentor texts.

- Physical spaces – Although teachers don’t always get to select the furniture and spacing in the room, if possible, having moveable desks/tables, cozy reading nooks, and conferring spaces can encourage collaborative work.

The social characteristics of a supportive writing environment include developing a community of writers and setting the expectation that writers collaborate. Buddy reading, shared writing, and discussion support writers who have ideas but are hesitant or unable to write.

Individual children’s needs – Choice is one of the strongest motivations to write. During writing instruction, teachers should provide children with choices of topic, genre, process, and spaces to write. To help children make choices, they will need to be provided with tools to identify and evaluate the available choices, otherwise, too many choices may be overwhelming. Conferring with children provides the teacher with an opportunity to provide timely feedback and instruction.

Intentional Writing Instruction

Writing is a complex task and to become better writers, children need direct and intentional instruction on the craft of writing, along with significant time to write.

Using the language of 6+1 Traits of writing, teachers support writers through mini-lessons, small group instruction, and in conferences. Explicit and direct instruction of English conventions and sentence construction, using authentic texts (children’s own writing or mentor texts) helps writers gain skill in manipulating language.

During genre studies, children are exposed to a variety of texts in the genre and identify the characteristics of the genre so they can use the characteristics in their own writing. In addition, teachers introduce the characteristics of disciplinary genres, such as lab reports or cause/effect writing in history.

Scaffolding during writing instruction can be done with different levels of support:

-

- Shared Writing – Children dictate the writing to the teacher. Often done on a whiteboard, large chart, or projected screen, the teacher models the process of writing, a writer’s thinking, and correct conventions. After writing, children read and re-read the text.

- Interactive Writing – Children physically share the pen (or keyboard) with the teacher to compose the writing together. Teachers provide strong support in stretching out words for children to spell, guide thinking about the writing through questions, and will write parts of the piece that are too hard for the children to do alone.

- Guided Writing – Typically done in small groups or individually, children begin writing but need more frequent feedback and instruction to be successful.

- Independent Writing – Children write mostly on their own; teachers conduct conferences to provide support and feedback.

Writing Assessment

Writing assessment will be described in more detail in Section 5. However, characteristics of effective writing assessment include a balance of:

-

- Self, peer, and teacher feedback and assessment

- A variety of methods – checklists, rubrics, discussion, and conferring

- Formative and summative

In addition, feedback needs to be ongoing and immediate to support improving writing while in the process of writing.

Section 4 – Technology and Writing

The Common Core State Standards require that students “use a variety of digital tools to produce and publish writing, including collaboration with peers.”

Technology has changed the way we write. Rather than long, detailed handwritten letters of the 18th and 19th centuries, people write Tweets of 28) characters, record TikToks or Snaps of 30 seconds, or post a picture to Facebook or Instagram to stay in contact with family and friends.

Writing instruction needs to reflect the demands of the 21st century, and this includes composing in multimedia and in collaboration with others.

Clearly, the word processor has had the greatest recent impact on how people write, by providing ease of revision and editing with spelling and grammar tools to improve writing. In addition, webbing and mind-mapping software such as Inspiration supports the writing process and access to the internet provides easier research and publication opportunities.

With technology constantly changing, the tools available for writers expand every day, but this chapter will attempt to highlight some of the main areas that technology can be used to enhance writing instruction.

Resources

The best way to become a better writer is to write and there are several websites, programs, and applications that can encourage children to write.

- Pen Pals

- EPals – https://www.epals.com

- PenPal Schools – https://www.gopangea.org/

- Interactive tools

- Read Write Think Interactive Tools – http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/student-interactives/

- PowToons – https://www.powtoon.com/

- Padlet – https://padlet.com/

- Popplet – https://www.popplet.com/

- Simple Mind –https://simplemind.eu/

- Skill-based

- Fun English Games – http://www.funenglishgames.com/writinggames.html

- PBS games – http://pbskids.org/games/

- Grammar

- Grammaropolis – https://education.grammaropolis.com/

- Grammar Pop – https://static.macmillan.com/static/QDT/grammar-pop/index.html

- Madlibs – https://www.madlibs.com/apps/

- Handwriting

- iTrace (Apple only) – https://itraceapp.com/en/

- Letter School – https://www.letterschool.com/

- iWrite Words (Apple only) – https://www.gigglelab.com/iwritewords

- Creative writing

- Storybird – https://www.storybird.com/

- My Storybook – www.mystorybook.com

- Story Jumper – www.storyjumper.com

- Story Wheel – https://storywheelapp.com/

- Story Dice – https://thinkamingo.com/story-dice/

Section 5 – Writing Assessment

Not every piece of writing needs to be assessed. That may sound radical, but if children are going to write often and in a variety of genres, teachers can not assess every piece of writing produced. However, children need frequent and “just in time” feedback and correction to become better writers. Teachers provide ongoing feedback and assessment through a variety of tools. These tools can be used by children for self-assessment, with a peer for revisions, or with an adult for instructive feedback and evaluation.

Checklists – Checklists help children review and recognize the strengths and needs of their writing. Providing a short list of attributes to look for in the writing, children, alone or with a partner, can review the writing and check off the attribute. This first stage of revision or editing provides opportunities for children to be more independent.

-

- Project Based Learning Checklist Maker – http://pblchecklist.4teachers.org/index.shtml

- Student Treasures Checklists –https://studentreasures.com/blog/teaching-strategies/writing-and-editing-checklists-for-elementary-schoolers/

- This Reading Mama Checklists –https://thisreadingmama.com/free-editing-checklists/

Rubrics – Although rubrics can be used during revision, they are most often associated with summative assessments of processes or products. A rubric includes a list of criteria on one side and descriptors of achievement levels on the other side. The criteria can range from very basic, such as:. The story has a beginning, middle, and end; to more complex.

Teachers often provide rubrics for children, but a powerful learning opportunity occurs when children are involved in identifying criteria and descriptors because they are engaged in reading like writers.

Rubric Resources

-

- Rubistar – http://rubistar.4teachers.org/index.php

- Schrock Guide for Educators – http://www.schrockguide.net/assessment-and-rubrics.html

- Teacher Planet – http://www.teacherplanet.com/rubrics-for-teachers?ref=rubrics4teachers

Conferring – One of the most powerful ways to provide feedback to children is through conferences. Typically one-to-one, but sometimes in partners, teachers can provide immediate and specific compliments, comments, questions, and teaching points based on a child’s current piece of writing.

Portfolios – A portfolio is a collection of children’s work that shows progress over time. There are different purposes to portfolios, such as an ongoing, work-in-progress portfolio or a showcase portfolio of selected pieces.

Examples of Porfolios

Four Parts of a Writing Conference

Research – When entering the conference, teachers need to figure out what feedback would be most helpful for the writer. Asking children to describe what they are working on or what writing techniques they are attempting are typical ways to start a conference. The goal is to support children in articulating their thinking about their own work.

Decide – As the teacher listens to children, they will decide on something to say to the writer to push them forward in their writing. This combines what the teacher knows about writing (which is why teachers need to be writers) and what they know about the child. Teachers think about questions like the ones below:

-

- What would help most at this time?

- What would bring quick success?

- What would be a stretch, a risk, or a challenge?

- What is not likely to come up in whole-class instruction?

- Is this something I need to reteach or extend?

- What is the balance of curriculum I have offered this student?

- What kind of teaching would this student like me to offer? (Ray, 1999. pgs. 165-166)

Teach – Once a teaching point has been decided on, the teacher needs to teach it. The “lesson” should be short and build from what the child has done. The teacher should highlight the statement or thinking the child exhibits or something from the writing or use a mentor text. To help the child grasp the concept, the teacher needs to name it – for example, the teacher might talk about the lead, or shifting perspectives, or organization structure. Then the teacher should explain the purpose of the lesson – why the technique, strategy, skill, etc. is important. Then model how to do the skill, strategy, or technique. Often teachers will have children restate the lesson to check for understanding.

Record – It is important to record the content of the conference. It provides accountability for both the teacher and writer, documents ongoing instruction to inform future instruction, and shows patterns of instructional needs across the class.

Review & Questions to Ponder

Questions to Ponder

- Reflect on your experiences with writing in school. What methods did your teachers use to teach writing? What was effective/ineffective for you? Do you view yourself as a writer? Why/why not? How might this influence your own teaching of writing?

- The National Writing Project (NWP) is an amazing resource for teachers. Take some time to explore the website and its resources. https://www.nwp.org/

- Then review the Flint Hills Writing Project, which is Kansas’s local project that provides training and support for writing teachers http://fhwp.org/