1 Comprehensive Literacy Instruction

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is comprehensive literacy instruction?

- What practices support effective literacy instruction?

INTRODUCTION – Literacy in the 21st Century

To be a literate person in our modern age, a person must be able to do so much more than just read and write. Beyond traditional reading books or newspapers and writing letters or papers, the literacy demands of our modern times incorporate a wide range of ways to represent ideas and communicate.

Think about all the encounters you’ve had with texts in the last 24 hours. Planning a road trip? Google Maps, Trip Advisor, or VRBO. Organizing a group project? Group Me or Slack. Connecting with friends? Facebook, Instagram, or Snapchat. The ways and means of communicating is changing daily and our definition of literacy needs to change with it.

A comprehensive view of literacy instruction considers the “three reciprocal modes of communicating: speaking/listening; reading/writing; and viewing/representing” (Gambrell, Malloy, Janice, & Mazzoni, 2011, pg. 7). Children need explicit instruction and practice in both the receptive modes of communication (listening, reading, viewing) and the expressive modes (speaking, writing, representing). The Common Core State Standards has also adopted this comprehensive view of literacy instruction, including specific standards for foundational skills of reading; reading of informational text and literature; writing; language use; and speaking and listening. Plus, there is an increased focus on literacy instruction across content areas.

To address the comprehensive nature of literacy instruction, there are several classroom practices that support children in not only becoming literate but in becoming lifelong readers and writers. We will be advocating for these practices in this course (some adapted from Gambrell & Morrow, 2015).

Practice 1: Use a balanced approach to literacy instruction.

Practice 2: Create a classroom culture that fosters literacy motivation by providing choice, collaboration, and relevance in literacy instruction.

Practice 3: Build on children’s funds of knowledge and their interests.

Practice 4: Provide children with scaffolded instruction in the Five Pillars of Reading Instruction (National Reading Panel, 2000) – phonemic awareness; phonics; fluency; vocabulary; and comprehension.

Practice 5: Provide children with multiple opportunities to read a wide range of texts in a variety of genres.

Practice 6: Recognize that literacy is a social practice.

Practice 7: Provide children with literacy instruction using appropriately leveled texts to support the reading of increasingly complex texts.

Practice 8: Use a variety of assessments that reflect the dynamic and complex nature of literacy to inform instruction.

“The goal of comprehensive literacy instruction is to ensure that all achieve their full literacy potential. This instruction should prepare our students to enter adulthood with the skills they will need to participate fully in a democratic society that is part of a global economy. Students need to be able to read and write with purpose, competence, ease, and joy. Comprehensive literacy instruction emphasizes the personal, intellectual and social nature of literacy learning.”

(Gambrell, Malloy & Mazzoni, 2011, pg. 18)

Section 1 – Practice 1: Use a Balanced Literacy Approach

Practice 1: Use a balanced approach to literacy instruction.

Balanced literacy is not a curriculum or a program, but rather a framework for instruction that incorporates the best of known practices to reach and teach each child in the classroom. For years debates have worn on about the two most common approaches to teaching literacy, known as the “Reading Wars” which pitted phonics (explicit instruction in the sound/symbol relationship of letters that form words) and whole language (meaning emphasis of whole word instruction) against each other.

| APPROACH | DEFINITION | PRACTICES |

| Bottom-Up

(Phonics Focused) |

Focus on decoding by associating letter-sounds with the letter. Parts add up to the whole. |

|

| Top-Down

(Whole Langauge) |

Focus on meaning-making with later emphasis on skills. The whole motivates learning of the parts. |

|

| Interactive

(Balanced) |

Decoding and meaning-making happen simultaneously |

|

Each of these approaches work well with some children, but not all. In the 1990s, a balanced approach was introduced which emphasized drawing from the most effective pedagogical practices from phonics/whole language; teacher responsibility/student responsibility; explicit instruction/student choice; and whole group/small group/ individual instruction. Although termed “balanced instruction,” it does not mean a 50/50 split of forms of instruction, but rather focuses on “a decision-making approach through which the teacher makes thoughtful choices each day about the best way to help each child become a better reader and writer” (Spiegel, 1998 p. 114). Balanced literacy is NOT whole language with a new name. It is a comprehensive approach that recognizes the complexities of literacies in multiple contexts and honors the need for explicit, systematic, and direct instruction WHILE fostering a love of reading by attending to the whole child – their likes, dislikes, motivations, interests, background knowledge etc.

Children need to understand the alphabetic principles of language, make meaning from what they read /write /speak /hear, and develop of love for literacy that will last a lifetime. Oral language is integral in literacy instruction, however, much of the focus in classrooms is on reading and writing alone, as these skills require more obviously direct and explicit teaching.

One way to think about organizing instruction in a balanced literacy environment is to consider ways to incorporate activities in which reading and writing are done “to, with, and by” children (Mooney, 1990) sometimes known as the Gradual Release of Responsibility (GRR) model (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983). Typical balanced literacy approaches will include the following activities throughout the day and will be a mixture of whole group, small group, partner, and independent work.

| ACTIVITY STRUCTURE | TO, WITH, OR BY CHILDREN | DEFINITION |

| Reading Aloud | To | The teacher intentionally selects a text to read to children to teach skills, strategies, vocabulary, or for enjoyment. |

| Shared Reading | With |

The teacher intentionally selects a text to read to children to teach skills, strategies, vocabulary, or for enjoyment |

| Guided Reading | By |

A small group of children with similar instructional needs works with the teacher to develop skills and strategies through explicit instruction. |

| Independent Reading | By |

Children read independent books of their choice. |

| Modeled Writing | To |

The teacher writes in front of children, often using Think-Alouds to model various forms of writing, the process of writing, and authorial choices when writing. |

| Shared/Interactive Writing | With |

The teacher and children compose a text together. |

| Guided Writing | By |

A small group of children with similar instructional needs works with the teacher to develop skills and strategies through explicit instruction. |

| Independent Writing | By |

Children write independently based on topics of their choice. |

| Word Work | With |

Differentiated word study through individualized phonics and spelling work. |

With the publication of Common Core State Standards, there has been a renewed focus on the elements of speaking and listening; a stronger focus on deep, close reading of complex texts; and literacy instruction across subject areas. According to Cohen and Cowen, “The primary goal of a balanced literacy program is not to teach reading [literacy] as a skill broken into isolated steps, but as a lifelong learning process that promotes higher order thinking, problem-solving, and reasoning” (2011, pg. 37).

Section 2 – Practice 2: Create a Classroom Culture That Fosters Literacy

Practice 2: Create a classroom culture that fosters literacy motivation by providing

choice, collaboration, and relevancy in literacy instruction.

Illiterate – Unable to read and write

Aliterate – Able to read and write, but unwilling to do so

An old idiom states, “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.” In other words, you can show people how to do things, but you can’t make them act.

As literacy teachers, we need to show children how to read/write, but we also need to show children why to read/write. With extrinsic motivation to read and write, children may be compliant with our instruction, but intrinsic motivation will help them become life-long readers and writers. Many extrinsic motivators have been used in schools including grades, reward programs, competitions, and shaming. These external motivators may work in the short term, but frequently children either shut down when they do not succeed, work with minimal effort, or lose interest in reading/writing. In Kohn’s (1999) words, they are “punished by rewards.”

Intrinsic motivation, or the personal satisfaction of doing or completing an activity, supports children in becoming independent learners and developing self-efficacy (belief in one’s own abilities to deal with various situations). The reward of the activity is the activity itself. Children will be more intrinsically motivated to read and write when they have choice in the books they read and topics they write about; collaborate with others in their work; and recognize the relevancy in their work.

Choice – Children’s self-selection of books has been shown to have a more significant impact on comprehension and recall than the readability level of the text, according to the seminal report Becoming a Nation of Readers (Anderson, Hiebert, Scott, Wilkinson, Becker, & Becker, 1985). In addition, self-selection impacts children’s development of a positive disposition to reading (Gurley, 2012). Choice empowers students to make decisions; values their voice; supports deeper conversations about texts; develops deeper relationships with peers and the teacher; and fosters independence (Skeeters, Campbell, Dubitsky, Faron, Gieselmann, George, Goldschmidt, & Wagner, 2016).

CHOICE MATTERS

I’ve seen the incredibly powerful impact of choice on my students’ writing.

I’ve worked with struggling writers. I’ve worked with reluctant writers. I’ve worked with Kindergartners who could not even write or match their name on the first day of school.

And all of these children grew to become more motivated, engaged writers. They came to view writing as a way to tell their stories, teach others, and make real changes in their school and community.

I’m not a miracle worker and I’m not a perfect teacher (sooooo very far from it).

But I’ve given my kids choice in:

What they write about

The strategies and techniques they use

Their writing pace, and

Their tools and writing spots

And this has made all the difference!

It definitely doesn’t happen overnight, but I’ve seen kids go from needing teacher support to write a single sentence to drafting entire stories independently. And yes, that also takes a lot of intentional teaching, but providing choice has played such a big role in those kids’ successes.

Alison, Former classroom teacher, currently a literacy specialist and consultant

http://learningattheprimarypond.com/writing/student-choice-in-writing-workshop-primary-grades/

Choice is also important in writing instruction. Similar to choice of texts, choice in topics and writing strategies provides children with a sense of agency; increases engagement in the writing process; and supports independence.

Collaboration – The first standard in the Common Core State Standards for Listening and Speaking requires collaboration. It states, “CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1 Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.” The literacy classroom is an ideal space for children to converse and collaborate on their reading and writing.

Meaningful talk about text is an essential strategy to enhance comprehension. Too often teachers control the conversation about books, but student-initiated and student-led conversations increase motivation, engagement, authentic discussion, and comprehension (Gregory & Rozzelle-Nikas, 2005).

Hoogeven and van Gelderen’s (2013) meta-analysis of 26 studies that focused on peer collaboration during writing with young children indicated that working with peers had a positive effect on writing performance, development of ideas, revision, quality of texts, productivity, and dispositions about writing.

Relevance – Since the literacy demands in society have changed, literacy instruction needs to change too. Literacy in the 21st century requires more than simply reading and writing. Children need to be engaged in literacy tasks that are authentic, challenging, and involve critical thinking and multimedia. Children need to read authentic books, both fiction and informational, and write or represent their ideas for authentic audiences using both traditional and non-traditional formats like video and social media.

Active, project-based, and authentic literacy tasks can be more relevant than worksheet-based instruction.

Section 3 – Practice 3: Build on Children’s Knowledge and Interests

Practice 3: Build on children’s funds of knowledge and their interests.

“For culturally relevant literacy curriculum to be effective, we, as teachers, need to be truly committed to learning from our students, honoring the funds of knowledge that they bring from their families, cultures, and communities, and allowing ourselves to be changed in the process.”

Katherine Wurdeman, Thurston Kaomea and Julie Kaomea (2015, pg. 434)

Funds of Knowledge – Children come into our classrooms with experiences that are uniquely their own. They each have different academic, social, cultural, familial, and personal knowledge and experience. This knowledge and experience are resources that teachers can draw from, link to, and make connections with – if the teacher understands the child’s funds of knowledge.

Luis Moll, Cathy Amanti, Deborah Neff, and Norma Gonzalez define funds of knowledge as “the historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills essential for household or individual functioning and well-being” (2005, p. 133). To access children’s funds of knowledge, teachers need to shed the role of expert and become a learner. Teachers become researchers of their students by being in their students’ communities; inviting students’ families into the classroom; and eliciting and valuing the language and culture of their students.

Connecting to Children’s Interests – Curriculum needs to be dynamic and respond to the interests of the children in the classroom. One year it might be dinosaurs, but the next year it might be Pokemon.

When a child is interested in a topic, the child is more likely to be engaged and motivated to learn. This seems like an obvious statement, but too much of the work in the classroom is dictated by the teacher with limited connections to children’s interests.

Teachers can learn about a child’s interests through Interest Inventories or Interviews; asking family members about the child’s interests; and most importantly, talking with and observing the child.

Building on Children’s Strengths – A strengths-based approach to education is focused on identifying and building on students’ strengths, rather than focusing on only remediating students’ weaknesses. This is in direct contrast to the deficit thinking that is still present in many classrooms (Chubbuck, 2010) which identifies what students are lacking. In recent years, strengths-based education has been linked to Carol Dweck’s work on fixed vs. growth mindset. Building on students’ strengths increases their perception of personal agency and their ability to succeed in tasks, which increases engagement in learning.

By looking for and building on children’s strengths, children develop a more positive self-image and perception of their potential. In addition, it can positively impact teacher interactions with students and school culture by making it more inclusive, caring, and pro-social (Brownlee, Rawana, & MacArtthur, 2012).

Section 4: Practice 4: Five Pillars of Reading Instruction

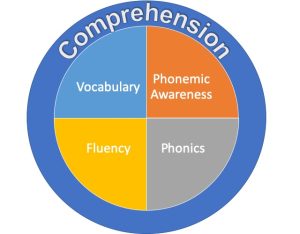

Practice 4: Provide children with scaffolded instruction in the Five Pillars of Reading Instruction (National Reading Panel, 2000) – phonemic awareness; phonics; fluency; vocabulary; and comprehension.

One of the most influential documents in teaching reading today was produced by the National Reading Panel in 2000. Titled Teaching Children to Read, the report reviewed research determined to be scientifically based (which limited the research it reviewed) to determine practices that seem to have more impact on reading achievement. The recommendations include reading instruction that is balanced and includes explicit, direct, and systematic instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

Phonemic Awareness – Phonemic awareness is the ability to notice, isolate, and manipulate sounds in words and sentences.

Phonics – Phonics deals with the phonological, or sound component of language, and it can be defined as the set of relationships between letters and sounds (or graphemes and phonemes).

Fluency – Fluency is the ability to read a text accurately, quickly, and with appropriate expression.

Vocabulary – Vocabulary is the ability to recognize, interpret, and use words across a variety of contexts.

Comprehension – Comprehension is a complex, meaning-making process that is an interaction of the reader, the text, the task, and the socio-cultural context.

Section 5 – Practice 5: Wide Range of Reading

Practice 5: Provide children with multiple opportunities to read

a wide range of texts in a variety of genres.

We all have a favorite type of book to read. Dr. Porath happens to love science fiction, but her mother loved true crime stories so they didn’t exchange books very much. Dr. Levin’s favorite genre is historical fiction. What’s your favorite genre?

Children tend to gravitate to a favorite style of book or author. In the early years, typical favorites include works by Mo Willems (Elephant and Piggy); Cynthia Rylant (Henry and Mudge); Beverly Cleary (Ramona); Elisabetta Dami (Geronimo Stilton); Annie Barrows (Ivy and Bean); Louis Sachar (Wayside School); Jennifer Holm and Matthew Holm (Babymouse); Nancy Krulik (Katie Kazoo); and Megan McDonald (Judy Moody) – just to name a few.

However, a wide range of reading provides children with different perspectives; increases their worldview; develops their vocabulary; and increases the likelihood they will become lifelong readers.

To create what she calls, “wild readers” Donalyn Miller (2013) recommends five habits to develop in the classroom:

- Dedicate time to reading

- Successfully self-select books

- Share books with others

- Have a reading plan

- Validate and expand children’s reading preferences

As teachers, we need to be aware of how our own preferences in reading might influence our students’ perceptions of texts. If I’m not a fan of mysteries, my classroom library may not include many mysteries, I might not recommend a mystery to a child, and I might steer children to a different genre since I know very little about mystery titles. As you read this paragraph, substitute the genre you are least familiar with or dislike and consider how it might impact your classroom.

Finally, read alouds are an essential part of developing children’s wide range of reading. Children can comprehend and engage in texts above their independent reading level, when the text is read aloud and scaffolded by the teacher. Interactive read alouds support the development of fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension, and they are an enjoyable, community-building event.

Section 6 – Practice 6: Literacy is a Social Practice

Practice 6: Recognize that literacy is a social practice.

In terms of your classroom, it is important to ask, What kinds of social practices are in place and, as a result, how is literacy being defined? Who benefits from this definition of literacy? Who is put at jeopardy? What social practices would I have to put in place to make the everyday literacies that students bring with them to school legitimate? What kinds of things would I have to do to show that I honor the home literacies that students bring with them to school? What would I have to do to expand what it means to be literate in the 21st century?

Jerome Harste (2003)

What was literacy instruction like when you went to school? Did you have weekly spelling lists? Did you get to select your own books to read? Did you have Accelerated Reader quizzes with points? Did the literacies of your home match what was expected of you in school?

Most likely, your home literacies were compatible with the literacies valued at school. However, this is not true for all children.

People’s use of language and literacy depends on the context. Consider the style and format of language that you use for a causal text to a friend compared to a thank you note for a gift, or a phone call to check-in with your parents compared to a phone call to set up an interview. As an adult, you have developed the ability to assess the context, review your repertoire of language, and select the form most appropriate for the situation. But, have you ever been in a situation where you felt that the people around you were speaking a different language (even if they weren’t) and acting in ways that were confusing to you? This illustrates what it means to consider literacy as a social practice.

The ways people use language and literacy are “inextricably linked to cultural and power structures in society” according to Street (1984, pg. 433) and recognizes that there are multiple literacies. Barton and Hamilton (2000) outlined six propositions about the nature of literacy:

- Literacy is best understood as a set of social practices; these can be inferred from events that are mediated by written texts

- There are different literacies associated with different domains of life

- Literacy practices are patterned by social institutions and power relationships, and some literacies become more dominant, visible, and influential than others

- Literacy practices are purposeful and embedded in broader social goals and cultural practices

- Literacy is historically situated. Literacy practices change, and new ones are frequently acquired through processes of informal learning and sense-making. (p. 8)

When teachers recognize that literacy is a social practice, teachers value the literacies that children bring to school; become critical of the literacies we teach; and provide access to the literacies children need to be successful in life.

Section 7 – Practice 7: Leveled Texts

Practice 7: Provide children with literacy instruction using appropriately leveled texts

to support the reading of increasingly complex texts.

Think about a book that you found to be very difficult to read. What made it difficult? The topic of the book? The style of writing? The vocabulary? The purpose that you were reading it for?

When teachers talk about leveled texts, there is a variety of meanings to the term. It may be a specific number or label that indicates a score derived from a formula, or it may be a more general notion that the book is “Just Right” for a child. But the ultimate goal is to match children to texts that they can read without being frustrated yet find texts that stretch their abilities.

In general, teachers typically use three levels of text in reading instruction – independent, instructional, and frustration level. These levels are dynamic for each child based on the child’s familiarity with the genre and background knowledge. For example, Invasion of the Overworld (a Minecraft novel) by Mark Cheverton, might be a frustration-level text for a child with no knowledge of Minecraft but would be independent reading for another child who is an avid player.

- Independent – the highest level of text that a child can read fluently and with comprehension without support. In oral reading, there would be an accuracy rate of 95% or higher. Children should be reading at their independent level with self-selected books during independent reading time – sometimes called Drop Everything and Read (DEAR) or Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) time.

- Instructional – the highest level of text that a child can read mostly fluently and understand with some support (adult or peer). In oral reading, there would be an accuracy rate of 90% or higher. Instructional-level texts are used during the majority of the day in read alouds, guided reading, and shared reading. This level is often associated with Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development.

- Frustration– books at this level are too difficult for a child to read with accuracy and comprehension, even with support.

Readability Formulas – There are several different quantitative formulas that count word length, sentence length, high-frequency words, and the complexity of sentences. Some of the most common formulas include Fry (1968) and Fliesch-Kincaid (Fliesch, 1948). In addition, many schools use Lexile scores or Accelerated Reader Program’s ATOS score.

All of these measures consider only the aspects of texts that can be counted, not the genre, purpose, or need for background knowledge. This means that with Lexile score of 910 (7th grade) for Mr. Popper’s Penguins by Richard and Florence Atwater is labeled more difficult than the 680 (4th grade) score for The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, which is typically a high school book.

To supplement the purely quantitive measures used in readability formulas, Fountas and Pinnell (1996) advocated for leveling texts in which educators consider other aspects of texts such as font type and size, amount of illustrations, genre, text structure, etc. Their system, often called Guided Reading Levels or Fountas and Pinnell Level are labeled A-Z+ and the F & P Text Level Gradient uses a range of levels to show progress in text complexity across the grade levels.

Two other typical leveling systems include Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA) and Reading Recovery (Clay, 1993). To see how various levels compare, look at the link in the sidebar.

Some less precise measures, such as the Goldilocks Strategy (Ohlhausen & Jepsen) and The Five Finger Rule (Allington, 2006) provides guidance for children when they are self-selecting books.

The Goldilocks Strategy asks readers to assess the books they encounter by asking a series of questions in three categories – too easy, just right, and too hard. See below for the questions.

| TOO EASY | JUST RIGHT | TOO HARD |

|

Have you read it lots of times before? |

Is the book new to you? |

Are there more than 5 words on a page you don’t know? |

|

Do you understand the story well? |

Do you understand a lot of the book? |

Are you confused about what is happening in most of this book? |

|

Do you know almost every word? |

Are there just a few words in the book that you don’t know? |

When you read aloud, does it sound choppy? |

|

Can you read it smoothly? |

When you read, are some places smooth and some choppy? |

Is everyone else busy and unable to help you? |

When children are browsing for books, they can use the Five Finger Rule (three fingers for emergent readers) to quickly judge the difficulty of the text in a book. After finding an interesting book, the child opens to any page of text and begins reading. The child holds up a finger for each word that is unknown. If the child holds up five fingers, the book is most likely too hard to read independently.

Choosing a “Just Right Book”

Using leveled texts should not label children with a particular number, letter, or score. Rather, the use of leveled texts provides an opportunity for teachers to quickly make instructional decisions that match children to accessible texts depending on the instructional purpose. Reading easier texts supports reading enjoyment and the development of fluency. Reading harder texts, with support, develops vocabulary and comprehension. Like other aspects of balanced literacy, the difficulty of texts needs to be balanced throughout the day too.

Section 8 – Practice 8: Varied Assessment

Practice 8: Use a variety of assessments that reflect the dynamic and

complex nature of literacy to inform instruction.

“Reading and writing are complex areas to assess. No single assessment can include all aspects of these complex processes. What’s more, there are multiple purposes for literacy assessment, and no single assessment can serve all purposes. Together, these facts make it clear that literacy assessment is much more complicated than many realize. In short, literacy assessment needs to reflect the multiple dimensions of reading and writing and the various purposes for assessment as well as the diversity of the students being assessed.”

Literacy Assessment What Everyone Needs to Know

International Literacy Association (2017, pg. 2)

When you think about assessment, what feelings come to mind? Dread, fear, anxiety, boredom, pride, excitement? Assessment is crucial in judging children’s progress and determining the next steps, but the overuse and misuse of high-stakes, summative, standardized tests have given assessment a bad name.

However, the tide is turning. Formative and informal assessments are again taking their rightful place in the classroom and providing data that educators can use to inform and adapt instruction to provide challenging and differentiated literacy instruction.

More depth on assessment will be provided in each chapter, tied to the particular literacy skill, strategy, or practice. But, to begin the discussion there are a few terms to know.

Summative assessment – Assessments that occur at the end of a unit of study, semester, or year. The goal is to judge progress without significant feedback to the learner. Summative assessments can be teacher-created such as an end-of-unit test, but may also be a state or national exam.

Formative assessment – Assessments that occur in the processes of learning to provide immediate feedback to the learner and information for the teacher to guide future instruction.

Formal assessment – Standardized tests that provide data in the form of scores, comparisons, grade-level equivalency, and/or stanines. State and national tests are formal. This would also include the ACT and SAT.

Informal assessment – Assessments that are content and performance-based. Some may be more structured, such as Running Records, Concept of Print Awareness, and Informal Reading Inventory. It can also be less structured such as observation, antidotal records, and discussion.

Authentic assessment – Assessments that mirror real-life situations, disciplinary work, or application of knowledge such as lab reports, presentations, demonstrations, or portfolios.

Teachers need to be proficient with a variety of assessments, know the purpose of the assessment, apply the assessment to the appropriate situation, know how to analyze and interpret the data, and use the results to guide instruction.

Assessment can be both a tool for the measurement of progress and support the process of learning. To accomplish both purposes, McTighe, discusses five principles for effective assessment:

• Ensure that assessment serves directing learning

• Use multiple measures

• Align assessments to goals

• Measure what matters

• Ensure that assessments are fair and equitable

Review and Questions to Ponder

Questions to Ponder

- Reflect on your elementary literacy experiences. What worked for you? What didn’t work for you? When were you engaged and motivated? When weren’t you? How might these experiences influence your literacy instruction in your classroom?

- Document your family’s funds of knowledge. What literacies practices were/are evidenced in your home? How might a teacher build on these funds of knowledge to design instruction?

- As a freshman or transfer student, you were provided a code for the StrengthsQuest assessment. When you completed the assessment, you were provided a report with your top five strengths. Find/review these strengths. How might you use these Strengths as a teacher? How might you discover your own students’ strengths?

StrengthsQuest Talent Descriptions

https://www.strengthsquest.com/193541/themes-full-description.aspx

References

References

Allington, R.L. (2006). What really matters for struggling readers: Designing research based programs (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Anderson, R. C., Hiebert, E. H., Scott, J. A., Wilkinson, I. A., Becker, W., & Becker, W. C. (1985). Becoming a nation of readers: The report of the Commission on Reading. Education and Treatment of Children, 389-396.

Barton, D. & Hamilton, M. (2000). Literacy practices. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton, & R. Ivanič (Eds.), Situated literacies: Reading and Writing in Context (pp. 7-15). London: Routledge.

Brownlee, K., Rawana, E. P., & MacArtthur, J. (2012). Implementation of a strengths-based approach to teaching in an elementary school. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 8(1). 1-12.

Chubbuck, S. (2010). Individual and structural orientations in socially just teaching: Conceptualization, implementation, and collaborative effort. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(3), 197–2010.

Delpit, L. (2006). Lessons from teachers. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 220-231.

Dewey, J. (1934/2005). Art as experience. London: Penguin.

Gambrell, L.B., Malloy, J.A., Janice F., and Mazzoni, S.A. (2011). Evidenced-based best practices in comprehensive literacy instruction. In Lesley Mandel Morrow, Linda B. Gambrell (Eds.), Best Practices in Literacy Instruction (pp.11-36). New York: Guilford Press.

Gregory, V. H., & Rozzelle-Nikas, J. (2005). The learning communities guide to improving reading instruction. Corwin Press.

Harste, J. C. (2003). What do we mean by literacy now?. Voices from the Middle, 10(3), 8-12.

Hoogeven, M. & van Gelderen, A. (2013). What works in writing with peer response? A review of intervention studies with children and adolescents. Educational Psychology Review, 25(4), 473-502.

International Literacy Association. (2017). Literacy assessment what everyone needs to know. Literacy Leadership Brief. Newark, DE: Author. Retrieved from https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/where-we-stand/literacy-assessment-brief.pdf

Miller, D. (2013). Reading in the wild: The book whisperer’s keys to cultivating lifelong reading habits. John Wiley & Sons.

Moll, L., Amanti, C., & Gonzales, N. (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Mooney, M. (1990). Reading to, with, and by children. Katonah, NY: Richard C. Owen, Publishers, Inc.

Ohlhausen, M. M., & Jepsen, M. (1992). Lessons from Goldilocks:” Somebody’s Been Choosing My Books but I Can Make My Own Choices Now!”. New Advocate, 5(1), 31-46

Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 317-344.