8 Fluency – The bridge between phonics and comprehension

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- Why does fluency make children strong readers and writers?

- In what ways can teachers promote and enhance fluency?

The Essentials of Fluency

“Fluency is the ability to read a text accurately and quickly. When fluent readers read silently, they recognize words automatically. They group words quickly in ways that help them gain meaning from what they read. Fluent readers read aloud effortlessly and with expression. Their reading sounds natural, as if they are speaking.”

Put Reading First, 2001

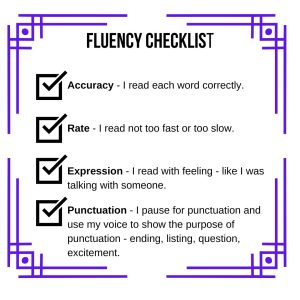

Think of what it means to be fluent in a language. The words need to flow from the child’s mouth without delay or effort, meaning they need to be able to conjure up the correct words and have the words combined into phrases and sentences with ease. And, this is true for fluency in reading and writing in any language. Children are fluent readers and writers when they can do so with sufficient ease and pace. Fluency with written language consists of multiple components: accuracy; automaticity; speed; and prosody.

Accuracy and automaticity are about reading words correctly and instantly with little to no delay to have to slowly decode or figure out unknown words. A student’s reading accuracy is expressed in a percentage of words correct per minute (WCPM), which is divided into three categories. If a child reads with 95-100% accuracy, they are at the Independent Reading Level meaning the text can be read with ease. A child who reads with 90-94% accuracy is at the Instructional Reading Level, and this means they read with relative ease but do not recognize all of the words and need to work at decoding unfamiliar ones. This is the ideal level for small-group reading instruction because it pushes students to try new strategies and exercise their skills. If a child’s accuracy rate is below 90%, then they are at the Frustration Reading Level, and just as its name implies, a text at this level is too difficult and will likely frustrate the child and impair comprehension.

Speed or reading rate is the pace at which a reader reads and it increases as children gain more accuracy and automaticity. Readers will slow their pace or speed up depending on the difficulty of the text they encounter, or their purpose for reading. There are grade-level norms for how many words correct per minute a child should be able to read as they develop their fluency from year to year. These assessments are typically part of the reading assessment package at the school district for screening, progress monitoring, and diagnostic assessment. If a reader reads too quickly or too slowly, it can interfere with the ability to make sense of what they read.

Prosody is about how the reading sounds. A reader with good prosody reads with adequate expression, intonation, pitch, volume, and phrasing. A reader with good prosody will read expressively, varying their voice and paying attention to their pace. A reader with poor prosody will often read in a slow laborious robot-like, monotone voice.

There is a direct connection between fluency and comprehension called the Theory of Automaticity. According to this theory, fluent readers direct relatively little effort to the act of reading, allowing them to focus active attention on meaning and message. Less fluent readers must direct considerable effort to the act of reading, leaving little attention for reflecting on its meaning and message (Foorman & Mehta, 2002; Samuels, 2002). The more automatic and effortless word recognition is, then the more brain power a child can devote to making sense of and understanding what they are reading. Therefore, it is critical that teachers spend time each day on activities to build students’ fluency.

This video from Reading Rockets features PBS Character Leo from Read Between The Lions.

Ways to Assess Fluency

If teachers want to determine how fluent a reader is, teachers need to listen to the reader read out loud and evaluate their accuracy, speed, and prosody.

To calculate reading accuracy, a child reads a piece of text that is at their reading level – a passage of about 100 words is adequate in length for this assessment. As the child reads, the teacher notes how many words they read correctly and how many errors they make. Subtract the number of errors from the total number of words they read, and then divide that number by the total number of words to get a percentage.

Accuracy = Total Words – Errors \ Total Words

Students should be given books at their instructional reading level during small group reading instruction. The teacher can use the slightly more difficult texts to teach skills and strategies and scaffold instruction to support students. In general, students should read books at their independent reading level when they are reading for pleasure, and generally, they should not be reading books at their frustration reading level because they are too difficult.

| 95% or higher | Independent Reading Level |

| 90-94% | Instructional Reading Level |

| Below 90% | Frustration Reading Level |

Reading Speed can be assessed by finding a reader’s Word Correct Per Minute reading rate (WCPM). To find this number, time a reader for sixty seconds and then count up the number of words they read accurately in that time. WCPM = Total Words Read Correctly in 60 Seconds. Click here for the Hasbrouck and Tindal (2006) Oral ReadingFluency Norms Chart to see the norms for reading fluency.

Finally, teachers can assess a child’s prosody by listening to how they read. Good prosody is defined as reading effortlessly with expression, proper phrasing, pitch, and intonation. We can use a simple rubric to determine the level of prosody. Click here for a rubric from Tim Rasinski that includes four factors of reading prosody.

To assess fluency fully, a teacher needs to measure all three components of fluency: accuracy, speed, and prosody. Then, a holistic determination of weaknesses can be made along with a plan of instruction.

The Problem with Round-Robin Reading and Some Alternatives

Many students have experienced “round-robin reading” practices in their education. Whether it was in reading class or in social studies, teachers often call on students, without warning or preparation, to read aloud chunks of text. Variations of this practice include:

- Popcorn reading – the teacher randomly calls on students

- Combat reading – students call on each other

- Popsicle reading – the teacher pulls popsicle sticks with students’ names to determine the reader

- Round-robin reading – the students read in order of seating chart

Think back to your own experiences with reading aloud in class. Was it positive? Did it encourage you to enjoy reading? How did your friends feel about it?

By the 1950s, there was clear evidence that round-robin reading was not an effective teaching practice, and in fact, it often had negative effects on students’ comprehension, fluency, and motivation and attitude towards reading (Kelly, 1995). However, this practice continues in many K-12 classrooms across the country. Teachers give a variety of reasons for using this practice: they experienced it and assume it is an effective teaching practice; they don’t have other strategies to support readers; it provides classroom control and management during reading; it ensures students are paying attention; it guarantees that all students “read” the text; it provides fluency practice; and some students love reading aloud (Hill, 1983; Ash, Kuhn, & Walpole, 2008).

Almost all of the reasons provided by teachers for using round-robin reading have been disproven by research (Kuhn, 2014). Round-robin reading actively works against fluency and comprehension as the text is chunked in small parts, read without previous practice (with limited focus on prosody), and students tend to read ahead. Unlike shared reading, it does not actively pursue meaning-making. As for classroom management, there are more off-task behaviors as students become bored with listening to the oral reading of their peers, which is slower than silent reading. Anxious or dysfluent readers may act out to avoid having to read aloud. Finally, round-robin reading decreases student engagement, enjoyment, and motivation to read (Hilden & Jones, 2012). Although, there are some students how do love to read aloud and will volunteer.

But, what are the alternatives? Depending on the goal of the oral reading practice, there are many alternative activities available:

- Reader’s Theater

- Partner reading

- Echo reading

- Choral reading

- Timed repeated reading (done individually)

- Reciprocal teaching

- Prepared and practiced readings (such as poetry)

- Whisper reading to self

- Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies (PALS)

- Teacher read aloud (to model fluency)

- Silent reading

- Practiced recorded reading – Crazy Professor Reading (instructions here) or Radio Reading

How To Promote Fluency in the Primary Grades

Sight Words

As the reading brain has become better understood, there has been a shift in the way teachers use the term sight words. In the past, teachers have used the terms sight words and high-frequency words as interchangeable, but they are NOT the same things.

A sight word is “any word that is recognized instantly, by sight, whether it is spelled regularly, irregularly, or something in between” (Moats & Tolman, 2019, pg. 211). This means that a child has encountered the word so often that the child no longer needs to sound it out.

In the past, sight words were mostly taught as words to memorize – often through flashcards or games. However, the science of reading has shown that this is an inefficient and ineffective way of learning words as the human brain can only memorize a few items at a time.

Instead, sight words should be taught explicitly, showing children how to sound out the regularly decoded parts, and only memorize the irregular, sometimes called “heart words” or parts of the word.

Examples of Teaching Heart Words – or Irregular Words for Sight Word Fluency

Really Great Reading – https://www.reallygreatreading.com/heart-word-magic

High-Frequency Words

One way to increase accuracy and automaticity is by building a large high-frequency vocabulary (Rasinski, 2003). High-frequency words are the most frequently occurring words found in texts. Educator Dr. Edward William Dolch developed the list in the 1930s-40s by studying the most frequently occurring words in children’s books of that era. The list contains 220 “service words” plus 95 high-frequency nouns. These words comprise 80% of the words found in a typical children’s book and 50% of the words found in writing for adults. Once a child recognizes most of these words, it makes reading much easier, because the child can then focus his or her attention on the remaining 20% of unknown words. The 315 Dolch sight words are commonly divided into groups by grade level, ranging from pre-kindergarten to third grade, with a separate list of nouns.

Examples of Sight Word Lists

Dolch Words – http://www.sightwords.com/sight-words/dolch/

Fry’s Word List – https://www.spelling-words-well.com/sight-word-list.html

Teaching Sight Words and High-Frequency words

Orthographic mapping can help children make the speech-to-print connection as the teacher models through multiple senses, how to take the word apart and put it back together again. Through orthographic mapping, children would explore the following:

| Word | Taking Apart by Sound

(Phonemic Analysis) |

Taking Apart by Spelling

(Orthographic Analysis) |

Alignment

(Orthographic Mapping |

| cat | /c/ /a/ /t/ = cat

3 sounds |

c-a-t = cat

3 letters |

/c/ /a/ /t/

c – at onset and rime |

| sheep | /sh/ /e/ /p/ = sheep

3 sounds |

s-h-e-e-p = sheep

5 letters |

/sh/ /e/ /p/

sh – ee – p 3 letter groupings (1 consonant digraph, 1 vowel digraph, and a consonant) |

Teachers use games, centers, read alouds, and word walls to teach sight words and high-frequency words. A new word is introduced to students and added to the word wall, and the teacher can read a book to the class pointing out every time that word appears. Then students can search for that word in a book of their choice, add the word to their desk dictionary, play a matching game with the word, or write the word using various mediums.

Teachers can increase a reader’s speed along with their accuracy through repeated readings (Dowhower, 1989). Each time a student rereads a text, their accuracy and speed will improve. Fun ways to practice repeated reading include using iPads to record a book for the listening center, paired reading with partners taking turns, and timed repeated reading. In a timed reading, students or teachers read short texts at their independent or instructional level, use a timer or stopwatch, and chart their progress on a time chart after each reading. Because they practice rereading the same text, their reading speed usually improves each time.

After each reading of the text, the students graph their results. These graphs provide students with immediate feedback, show evidence of fluency progress, and help motivate them to improve their fluency. Such feedback is critical for struggling readers who often get discouraged easily.

Timed repeated reading can be incorporated into the literacy block in a variety of ways. You may time the student at the beginning or end of small group instruction, or students may time themselves or a partner during literacy centers or independent work time. In addition, timed repeated reading can be paired with other fluency activities that provide a model of fluent reading, such as partner reading, student-adult reading, or audio-assisted reading.

Reader’s Theater is one of the most engaging and authentic ways to promote fluency and give kids practice with accuracy, speed, and prosody. In reader’s theater, small groups of students select characters and practice reading from a dramatic script until they are polished and ready to “perform” their play. Because there is no stage, props, or costumes, readers have to use their voices to give expression and meaning to the drama.

• Dr. Chase Young’s Reader’s Theater Scripts

• Aaron Shepard’s Reader’s Theater Editions

• Teaching Heart Reader’s Theater Scripts and Plays

More Fun Ways to Practice Fluency in the Classroom

More Fun Ways to Practice Fluency in the Classroom

-

Paired or “buddy” reading

-

Reread favorite books

-

Ham it up with a script

-

Record it

-

Listen to books

Review and Questions to Ponder

Questions to Ponder

- Why do children need to learn to read and write high-frequency words?

- How is my own fluency and am I modeling great prosody every time I read aloud?

- If I have just 15 minutes every day to devote to fluency instruction, what will I do? Which activities will I implement?

For Further Reading:

Young, C., Mohr, K. A. J., & Rasinski, T. (2015). Reading together: A successful reading fluency intervention. Literacy Research and Instruction, 54(1), 67-81.

References

Ash, G. E., Kuhn, M. R., & Walpole, S. (2008). Analyzing “inconsistencies” in practice: Teachers’ continued use of round robin reading. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 25(1), 87-103.

Dowhower, S. L. (1989). Repeated reading: Research into practice. The Reading Teacher, 42, 502-507.

Foorman, B. R., & Mehta, P. (2002, November). PowerPoint presentation at A Focus on Fluency Forum, San Francisco, CA. Available at: http://www.prel.org/programs/rel/fluency/Foorman.ppt

Hilden, K., & Jones, J. (2012). A literacy spring cleaning: Sweeping round robin reading out of your classroom. Reading Today, 29(5), 23-24.

Hill, C. H. (1983). Round robin reading as a teaching method. Reading Improvement, 20, 263-266.

Kelly, P. R. (1995). Round robin reading: Considering alternative instructional practices that make more sense. Reading Horizons, 36(2), Article 1.

Kuhn, M. R. (2014). What’s really wrong with round robin reading? Ask a Researcher. The International LItearcy Association Blot. Retrieved from: https://literacyworldwide.org/blog/literacy-daily/2014/05/07/what’s-really-wrong-with-round-robin-reading-

Moats, L. C. & Tolman, C. A. (2019). LETRS volume 1 units 1-4. Dallas, TX. Voyager Sopris.

Rasinski, T. V. (2003). The fluent reader. New York, NY: Scholastic Professional Books.

Samuels, S. J. (2002). Reading fluency: Its development and assessment. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp. 166-183). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.