Introduction: A World “Together Apart”

Shalin Hai-Jew

Social World Sensing via Social Image Analysis from Social Media (2020) is an extension of earlier work that I have done in exploring social imagery through manual coding in a prior book, Techniques for Coding Imagery and Multimedia: Emerging Research and Opportunities (2017). As sometimes happens with book projects, the obsession has continued even after the initial publication, and I have wanted to test the methods to see if more meaning-making may be achieved across different topics.

A colleague of mine working in higher education on a different continent was working on a collection about the roles of social media in interweaving transnational issues. My chapters went through the double-blind peer review process, revision, and were finalized for his collection, slated to be published in April 2020. Suddenly, the publisher exercised the escape clause in the contract after the company had to lay off a fifth of their workforce. This is not to say that academic publishing has not always been a little touch-and-go (although I have had a good run of luck with publishers for many years). Rather, this turn of events occurred because the world itself was on fire, and the publisher was acting under duress and force majeure, in the face of deep uncertainties caused by a novel zoonotic coronavirus.

The social world, at this moment, is roiling. Humanity is living through a global pandemic, with the ravages of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus leading to the COVID-19 disease in people in over 200 countries and on every continent except Antarctica. The viral threat is being studied by scientists from various disciplines, and government officials and policymakers are struggling to contain the viral spread through “social distancing,” hygiene, sanitation, and other measures. People are living through rolling lockdowns, with industries shut down, and mass population self-quarantines, with people’s lives at a standstill. Simultaneously, we are living through something that feels like the very sharp immediate moment as well as something echoic of history, prior outbreaks when mass swathes of humanity were lost.

Initially, I supported my colleague in querying yet another publisher to see if these chapters could find a home there. When that did not pan out and the former project editor went radio silent, I decided to decouple my chapters from the original project. And instead of going with a commercial publisher, I decided to query my university’s open-access publishing house, the New Prairie Press, to see if there might be interest. I have an interest in making the work available, and I do not have the luxury of a lot of time spent re-negotiating another publishing context and going through all the effort to get the works reframed to the editorial visions of other publishers and other editors. I am confident that this is the right path forward, given my re-orientation to meet expanded professional responsibilities. [Interestingly, the commercial publisher’s administrator initially said that they only put a hold on the publication and would continue the project once they got up to speed again. I let her know that the forwarded email I saw said that the project was cancelled and that all contents reverted back to the respective authors and co-authors. The publisher then wanted to use these chapters in other works that they were publishing, and I declined her request. She reviewed the terms of the contracts and ultimately agreed with me that once projects were cancelled, the publisher’s access to the original works also ended. All rights have reverted to me.]

This authored collection is comprised of seven chapters that are interrelated by a cross-cutting approach in the analysis of social media messaging (particularly imagery) and other contents. In another sense the works are readable in stand-alone ways. The text does not have to be read sequentially. There are five topical parts to this work.

An Extended Table of Contents (TOC)

Part 1: Global Public Health

1. “Emergent COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 in Social Imagery and Social Video: Initial Three Months of Viral Dispersion”

The pandemic potential of emergent SARS-CoV-2, a zoonotic virus which causes COVID-19, has captured the world’s attention, through formal mass media and informal social media (esp. social imagery and social video). This work explores multiple social imagesets (thousands of images) from Google Images (captured from various seeding terms related to the outbreak) and social video transcripts from Google’s YouTube platform to infer focuses of mass human attention in terms of (1) messaging and information sourcing, (2) meta-messaging and subtexts, and (3) invisibilities (what is not expressed). This compares the imageset messaging against mass media articles from the same time frame. This work has implications for a mass-scale social response to an unfolding global biosafety/biosecurity risk based on learning from more organic and emergent social communications.

Part 2: Protecting the Environment

2. “Transnational Meta-Narratives and Personal Stories of Plastics Usage and Management via Social Media”

Daily, people interact with plastic, a human-made material that may last for generations in the soils, the air, and the water, with health effects on humans, animals, and the environment. What are the transnational meta-narratives and personal stories of plastics on social media—on (1) a mass-scale digitized book corpus term frequency search, (2) social video sharing site, (3 and 4) two social image sharing sites, (5) a crowd-sourced online encyclopedia, (6) a social networking site, (7) a microblogging site, and (8) a mass-scale search term analysis based on time-based associations with correlated search terms? This work samples macro-scale stories of innovation (biodegradable plastics, bacteria that consume plastics), of lowering consumption, of plastic collection and recycling, of skimming the oceans of dumped plastics, and of mass-scale public awareness. There are also countervailing narratives of high consumption, resulting in overflowing landfills, plastics dumping on mountains and in rivers, and microplastics in people’s bodies.

Part 3: Asserting Human Rights

3. “Global Citizens against Socio-Technological Incursions on Privacy, Human Rights, and Personal and Social Freedoms: Temporary Pixels and Ephemeral Voices”

With the simultaneous advances in technologies across various fronts, private citizens have had to face their fears of government surveillance and over-reach and private industry manipulations of personal data for various types of sell. There is fear that individuals and humanity will be over-matched and outpaced, judged, bullied, and ultimately captured and constrained by technological enablements. This work explores the thinking, writ large, of threats to privacy, human rights, and personal and social freedoms, as expressed on social media. This uses game theory to inform an early and narrated game tree about the power and limits of online voices.

4. “Blowing Whistles on Transnational Social Media: From Micro-to-Mass Scales, Privately and Publicly”

Internal whistleblowing against perceived wrongdoing has long had a place in both public and private sectors; this activity is seen as enabling more effective business and governance by bring law-breaking, fraud, waste, theft, and other issues to administration attention. With the popularization of transnational social media, additional channels have opened that enable both private and public outreaches to external others. The low cost of entry and potential for wide reach may lead some to imagine that public attention is a net positive and will lead to its solution. However, such outreaches may have major downsides: intended and unintended audiences (attracting allies and detractors), the lack of hard power in public opinion and public pressure (in many cases), and “blowback.” This work explores some roles of social media in the whistleblower phenomenon and defines the “social whistleblower” phenomenon.

Part 4: Political Expression

5. “In Flames, In Violence, In Reverence: Physical Protest Effigies in Global and Transnational Politics from a Social Imageset”

The popularization of the Internet, the WWW, and social media, has enabled various populations around the world to be politically “woke” together, with varying levels of agreements and disagreements around a variety of issues, with conservatism around some and radicalism around others (generically speaking). In social imagery, there are visuals of various protest effigies, depictions of public figures representing certain values, ideologies, platforms, policies, attitudes, styles, stances on issues, and other aspects of the political space. In some cases, the political figures are stand-ins and stereotypes that may represent undesirable change and a sense of threat. The study of physical “effigy” in social imagery from Google Images may shed some light on the state of global and transnational protest politics in real space and the practice of using physical protest effigies to publicize social messages, attract allies, change conversations in the macro political space, to foment social change.

6. “Exploring the Transnational Allure of ‘Street Democracy’ via Twitter based on a Contemporaneous Real-World Case”

In the popular massmind, “democracy” seems to mean different things to different people. For some, it is something worth fighting, and demonstrating and dying for. For others, they cannot be bothered to engage in the minimal civil duties of staying informed and voting. This chapter involves the study of 16 contemporaneous social media accounts that were surfaced in a search for “Hong Kong protests” on the Twitter microblogging site to understand expresses senses of “street democracy”. The resulting Tweets were analyzed for topical content, sentiment, and meaning, using a combination of human close reading and computational text analysis (in NVivo 12 Plus). What do the popular senses of “street democracy” around the pro-democracy Hong Kong protests on the Twitter microblogging site a suggest about (1) its meanings to the demonstrators, and then what are some of the implications to (2) strategic and tactical international or external “democratic promotion” in the U.S. context abroad generally and towards Hong Kong specifically?

Part 5: Faux Human Interrelating

7. “The Remote Woo: Exploring Faux Transnational Interpersonal Romance in Social Imagery”

One aspect of globalization combined with information and communications technology (ICT) and social media is the advent of online data and resulting long-distance romances. The relationships that have come to the fore, though, are about transnational (and more local) romance scams perpetrated online that result in loss of funds, loss of time, loss of personal dignity, loss of personal reputation, and other harms. This work explores social imagery to better understand some of the messaging behind the “remote woo” and romance online and romance fraud and what insights these may provide on this issue, in this exploratory study.

Some technologies used

The technologies used in this work include the following (in a partial list):

- Social Media Platforms: Google Images, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Wikipedia, and Flickr

- Data Extraction Tools: NodeXL, NCapture, Google Correlate, and various web browser-based image downloaders

- Data Analytics Tools: NVivo 12 Plus and NVivo, LIWC2015, NodeXL, and Excel

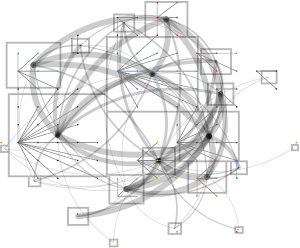

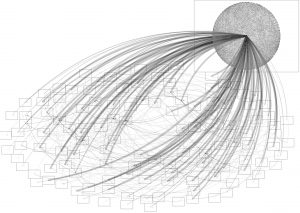

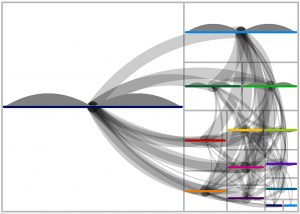

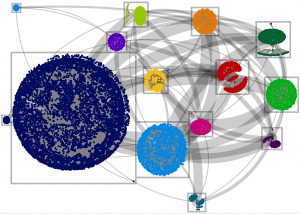

The decorative graphs used as separators were created by the author using NodeXL.

In physical biosafety lockdown…

I am hopeful that this text, Social World Sensing via Social Image Analysis from Social Media (2020), offers some insights about a complex world of so many peoples in their expressiveness and sharing. In a time such as this, how people connect over social media in mutual respect and caring and support will make all the difference in our mutual well-being. If nothing else, this moment reminds me of just how needful we are of each other, even in our respective solitude.

Thanks!

Thanks to Dr. Floribert Patrick C. Endong for his work on the initial edited text that ultimately did not make because of publisher pullback, based on the onset of SARS-CoV-2 / COVID-19. This is only one text, and there will be others. Every book involves blood and sweat, and sometimes, rarely, tears.

Thanks to faculty librarians Ryan Otto and Emily G. Finch at the Center for the Advancement of Digital Scholarship (CADS) at the Kansas State University Libraries for making this happen!

Thanks also to Scott Finkeldei (my supervisor) for his encouragement to pursue publishing with the New Prairie Press at K-State.

I am grateful to the makers of Pressbooks, who have made a very easy-to-use platform for creating online books.

(The image is a watercolor portrait of me by my son in his childhood many years ago!)

-

-

- Dr. Shalin Hai-Jew

- ITS, Kansas State University

- Spring 2020

- Dr. Shalin Hai-Jew

-