2 Global Citizens against Socio-Technological Incursions on Privacy, Human Rights, and Personal and Social Freedoms: Temporary Pixels and Ephemeral Voices

AbstractWith the simultaneous advances in technologies across various fronts, private citizens have had to face their fears of government surveillance and over-reach and private industry manipulations of personal data for various types of sell. There is fear that individuals and humanity will be over-matched and outpaced, judged, bullied, and ultimately captured and constrained by technological enablements. This work explores the thinking, writ large, of threats to privacy, human rights, and personal and social freedoms, as expressed on social media. This uses game theory to inform an early and narrated game tree about the power and limits of online voices.

|

Key Words

Socio-Technological Incursions, Privacy, Human Rights, Human Freedoms, Transnational Advocacy, Social Media, Surveillance Technologies, Civil Liberties

Introduction

“As long as there shall be stones, the seeds of fire will not die.” — Lu Xun (Zhou Shuren) (Sept. 25, 1881 – Oct. 19, 1936)

“As history teaches us, the character of warfare adapts to new circumstances. And as the saying has it, ‘Only the dead have seen the last of war.’” — Jim Mattis and Bing West in Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead (2019, p. 175)

“On the hill we had been at the start of something: of a new era in which conflict surges, shifts, or fades but doesn’t end, in which the most you can hope for is not peace, or the arrival of a better age, but only to remain safe as long as possible.” — Matti Friedman in Pumpkinflowers: A Soldier’s Story (2016, p. 222)

—

With the advent of various technologies—artificial intelligence, big data, data analytics, machine learning, near panopticon-level surveillance, video stitching, hacking and counter-hacking, affective computing, encryption and decryption, automation, the Internet of Things (IoT), implantable technologies, biometrics identifiers, and facial recognition software—people around the world have become somewhat more leery of the capabilities of nation-states to monitor their own citizens and to potentially enforce draconian laws with hyper-precision and force. Such concerns of government surveillance were found in an experimental study to lower the willingness to share personal information online (Dinev, Hart, & Mullen, 2008). Such tenets are core in many information-technology-based movements, such as the Anonymous hacktivist group (Hai-Jew, 2013) and other transnational movements. In the U.S., citizens have militated against the bulk collection of telephone metadata (under the U.S. Patriot Act), which has been widely covered in the mass media. This issue has come to the fore with the massive information theft of secret U.S. government data and its dump by Edward Snowden in 2013, the social credit system in China in 2020 [built on closed-circuit television (CCTV) and apps and other information], the mass demonstrations over multiple months in Hong Kong against a proposed extradition law of those in Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the mass incarcerations of Muslims in Northwest China for “re-education,” and others. There are fears that people will be deprived of their civil liberties in a panopticon and that all-seeing-ness of governments will force population compliance and passivity. There would not be the authentic and empowered “consent of the governed” but acquiescence, docility, submission, and tractability. Colloquially, the narratives go as follows:

- People require a sporting chance against their government and their incursions into their personal lives.

- Rights of one entity end where the rights of another’s begins, and there is a “zero sum” aspect to rights.

- Excessive buildup of personal citizen information enables a government to corrupt itself with too much power (via information and knowledge); it encourages heavy handedness in how governmental power shapes out and is expressed in the world. Personal citizen information builds in vast data farms contributes to the government arsenal of knowledge and control. It enables citizen profiling, physical locating and tracking, and other endeavors of regulation.

Based on what is known about technological capabilities, the concerns are many. How much is knowable for individual (pattern of life, psychology) and group profiling (capabilities, leadership, likely lifespan) through direct data collection and inference attacks? What are the privacy implications of mass and targeted surveillance? What do technological enablements allow for repressive governments that would see religious (or any other) identity as a threat and act on that fear? What happens to people’s personal and social freedoms in light of the fact that current technologies enable deeper knowledge of individuals (remotely): their professed values, their personalities (based on analyses of their expressions), their friendships, their expenditures, their real-time locations, their apparent politics, and other aspects? Is there a negative feedback loop possible based on “dataveillance” (data-based surveillance of persons in order to govern their behaviors), such as in a cycle where there is “recorded observation, identification and tracking, analytical intervention, behavioral manipulation” in a feedback loop that is endlessly recursive (Esposti, 2014, p. 213)? “Privacy” is defined as “the protection of unauthorized access to personal data” (Haunss, 2015, p. 227). “Privacy advocates” are those who are fighting “excessive surveillance” (Bennett, 2008, as cited in Bennett, 2012, p. 413).

Traditional concepts do not adequately capture the dynamic, volatile, overlapping and fragmented nature of privacy advocacy. There is certainly no clear structure. Neither is there a social movement with an identifiable base. Perhaps the best label is the ‘advocacy network’ which can be conceptualized as a series of concentric circles. At the centre are a number of privacy-centric groups, such as the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) in which other issues are peripheral and, if addressed, have to be entirely consistent with the core pro-privacy (or anti-surveillance) message. As we move out of the centre of the circle we encounter a number of privacy-explicit groups for whom privacy protection is one prominent goal among several; many of the civil liberties and digital rights organizations, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) or the EFF fall into this category. Within the outer circle, there is an indefinite number of groups, for whom privacy is an implicit or potential goal. Their aims are defined in very different terms—such as defending the rights of women, gays, and lesbians, the homeless, children, librarians, ethnic minorities, journalists and so on. Despite not explicitly focusing on privacy issues, the protection of personal information and the restriction of surveillance can be instrumental in promoting their chief aims. (Bennett, 2008, 57 – 61, as cited in Bennett, 2012, p. 415).

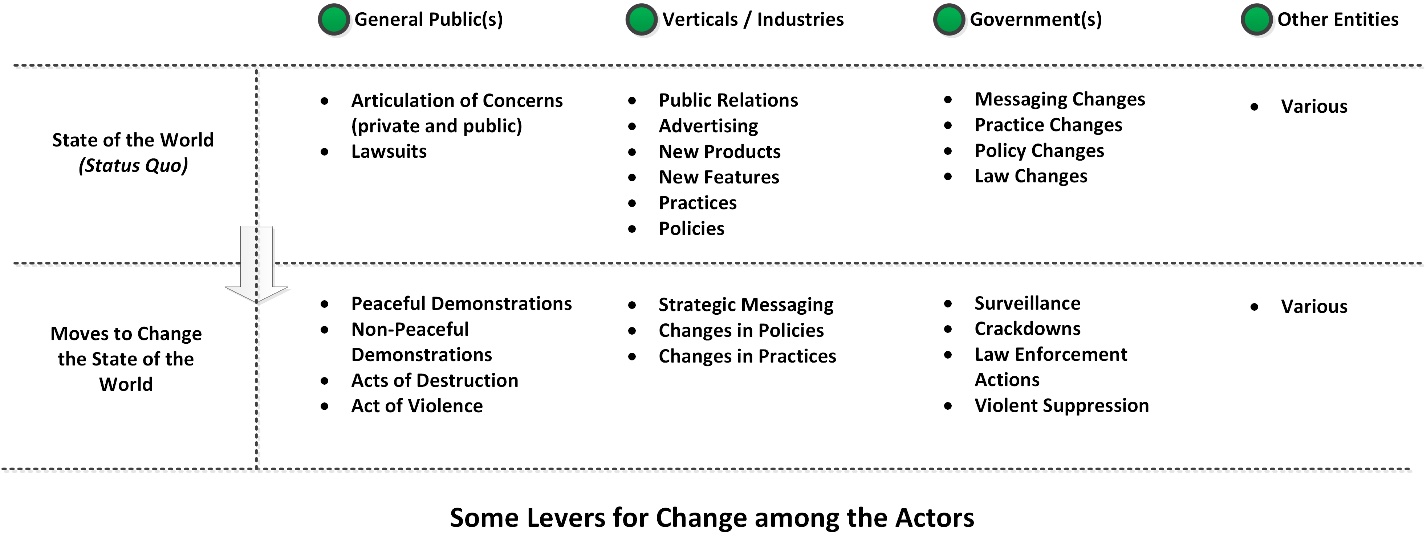

This issue is transnational because surveillance is “a global phenomenon” (Bennett, 2012, p. 415) and has to be challenged as such. The activists in this space are lobbying industries (particularly the few multinationals with wide global reach in this space) to change practices, both from within and without. They are lobbying various governments to change laws and practices. They are engaging other organizational entities, as well to advocate on their behalf and in support of their focal issue. Some of their general “power levers” are listed in Table 1. The highlighted cell between “General Public(s)” and “Social Media Messaging” is the focus of this work, with the base questions: “How potent are the temporary pixels and ephemeral voices online in support of transnational advocacy generally and this issue of human (privacy, human rights, individual and social protections) well-being against socio-technical incursions in particular? Why?”

|

Power Levers |

General Public(s) |

Vertical(s) / Industries |

Government(s) |

Other Entities (non-governmental organizations or NGOs, political organizations, non-profits, and others, as a catchall) |

|

Public Demonstrations |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Press Conference |

Occasionally |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Social Media Messaging |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mass Media Messaging |

Occasionally |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Courts of Law |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Government Levers |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Physical Force (at various levels) |

Occasionally |

Rarely |

Yes |

Occasionally |

|

Combinations |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Others |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Table 1: Strategic “Cards” for the Respective Stakeholder Groups based on Social Norms

For issues that are advocated to a global audience, social media are de rigueur because of its global reach. Of course, given geographical distances and socio-cultural factors, transnational issues are understood and manifest in different ways in different localities, based on more organic concerns. Transnational movements manifest in different ways in different locales (Lehoucq & Tarrow, n.d.), resulting in an uneven geographical distribution of activist hotspots. Certainly, the issues and threats also are perceived differently, and the on-ground understood threat profiles and scenarios (actors, technologies, applications, policy and practice environments, and others) vary. Also, this work is not usually a once-and-done but a continuing endeavor across a number of fronts. In most cases, transnational advocacy groups are working in a context of less power against better financed entities with inherent power (of corporations, of nation-states). Some have argued that most people are only signaling a few dozen people in the world who are in sufficient positions of power to make large-scale changes, in one sense. On the other hand, there are also the many others in the world with “hearts and minds” to be won over because global issues may be affected by individual actions as well. Public opinion also helps define an “authorizing environment” for policy makers, because of the importance of the “consent of the governed” (even beyond democratic societies and even among highly controlled populations). Another core assumption is that humans tend to be conflictual, to commit to their own sense of the world and to be less receptive to the ideas of others; people advocate for their own senses of an idealized future, and in public space, they compete with others for attention and sway.

Transnational advocates engage various tactics of sharing “politically usable information quickly and credibly to where it will have the most impact” (“information politics”); sharing “symbols, actions or stories” (“symbolic politics”); calling out “powerful actors to affect a situation” (“leverage politics”), and asking more powerful actors “to act on vaguer policies or principles they formally endorsed” (“accountability politics”) (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 95). Much of the organizing work then involves coalition building and maintenance, research, strategic and tactical planning, fund-raising, marketing and branding, budgeting, strategic communications, outreaches, and others. Throughout, those advocates that maintain the high ground and act in alignment with stated values tend to earn a place at the table for that issue and related peripheral ones.

So to answer the research questions, this work will involve exploring the academic research literature, some mass media news coverage, and some digital residua on social media and Web 2.0 (including social imagery from a recent and ongoing multi-month demonstration). From these, a basic partially explicated “game tree” will be created which represents the binary decision of advance or retreat at various phases of advocacy, up and down an escalatory ladder.

Review of the Literature

A “transnational advocacy network includes those actors working internationally on an issue, who are bound together by shared values, a common discourse, and dense exchanges of information and services” (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 89). A central effort involves the framing of issues “to attract attention and encourage action” towards policy change (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 90). Transformative social changes are seen as innovations, sparked by differing visions of the future as expressed in narratives (storytelling) (Wittmayer, Backhaus, Avelino, Pel, Strasser, Kunze, & Zuijderwijk, 2019). A number of actors in these networks include the following: “international and domestic NGOs, research and advocacy organizations; local social movements; foundations; the media; churches, trade unions, consumer organizations, intellectuals; parts of regional and international intergovernmental organizations; parts of the executive and/or parliamentary branches of governments” (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, pp. 91 – 92; numbering removed). An “electronic hive mind” (Hai-Jew, 2019) may be another construct that may be applied to the understanding of mass movements and decision making, albeit more in virtual space; certainly, empirically, people can be sparked to mass actions by messaging alone.

An informal summary of the mainline types of transnational advocacy issues include the following categories:

- human rights [“the right to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, the right to work and education” (“Human Rights,” 2019)] as a root inspiration, impacting development, basic health, human well-being, security, human dignity, anti-hate, and other aspects;

- pro-democratic institutions;

- free market trade;

- environmental protections;

- animal rights;

- economic development;

- conservatism related to biological and genetic modifications of food…and related research;

- anti-warfare;

- the rule of law and effective governance, and others.

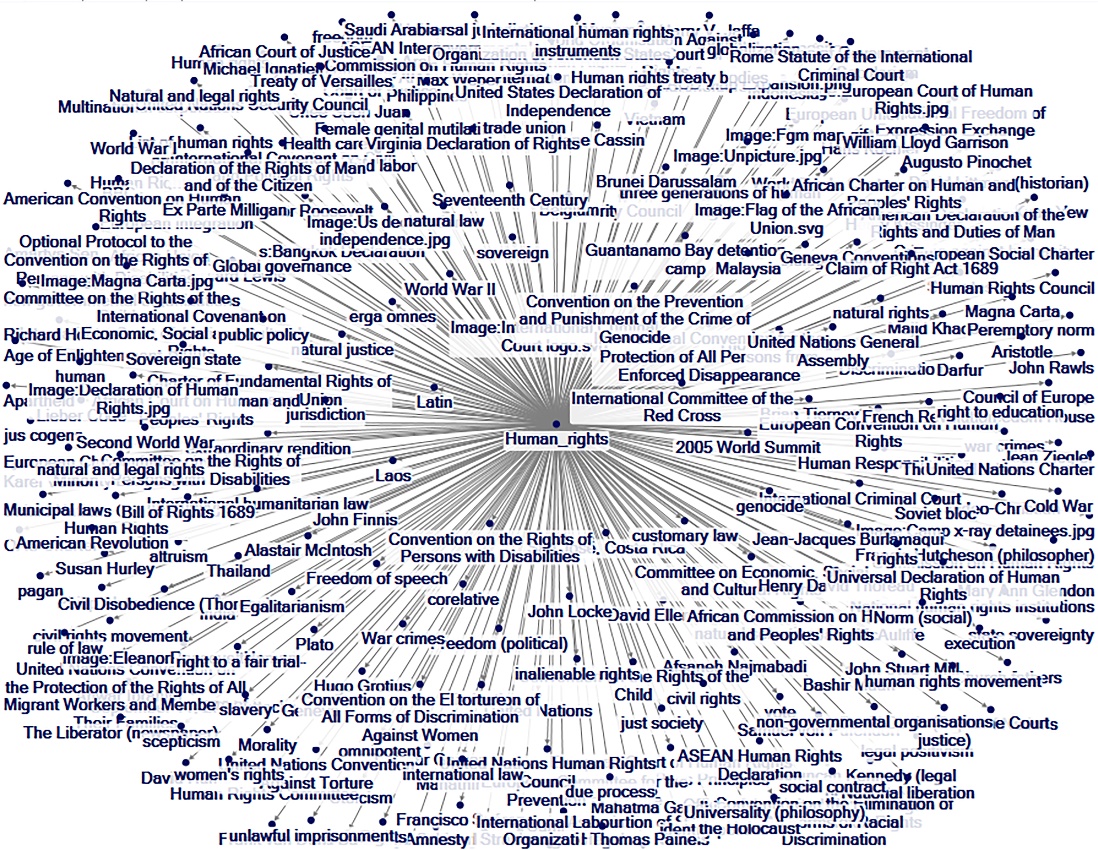

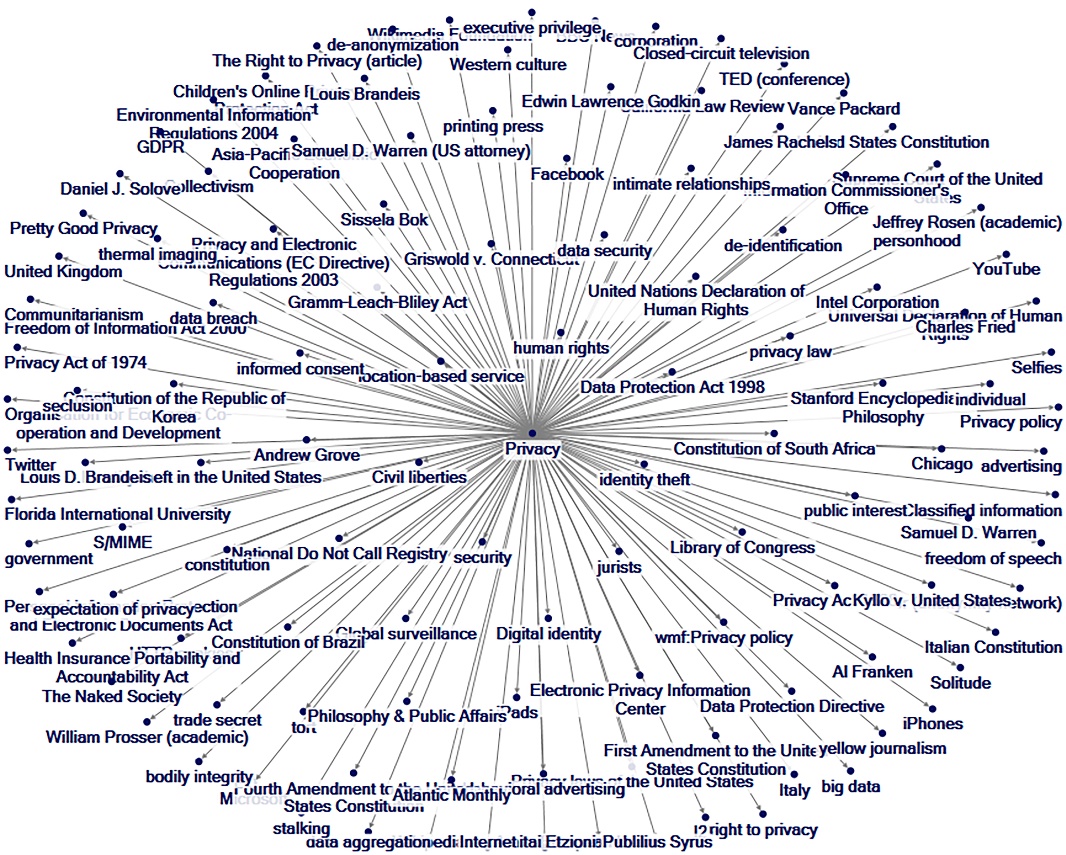

For many issues, there are advocates taking countervailing positions. Human privacy, human rights, and personal and social freedoms are essentially encapsulated in the first bullet under “human rights.” The concept is that these apply across national borders and so are the subjects of transnational advocacy. A visual sense of this may be seen in Figures 1 and 2. The first is an article-article network on “human rights,” and the latter is of “privacy,” both as one-degree networks on the crowd-sourced English version of Wikipedia, a global resource. The links are outlinks to other articles from the focal article node.

Figure 1: “Human Rights” Article-Article Network on Wikipedia (1 deg.)

Figure 2: “Privacy” Article-Article Network on Wikipedia (1 deg.)

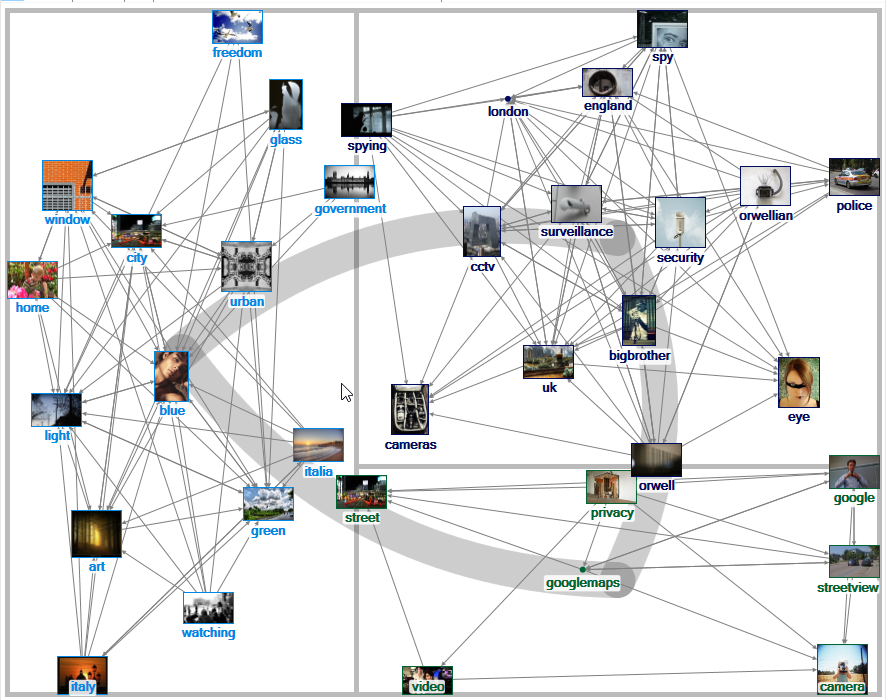

It is possible to explore “privacy” in related tags networks from a social image sharing site. Here, there are “folk” tags that are posted with image contents that are also tagged “privacy.” Some early insights: in terms of shared user-generated social imagery, “privacy” is expressed as something lived (“freedom,” “city,” “window, “urban”) in Group 1, as threatened (“spy,” “orwellian,” “surveillance,” “security,” “police”) in Group 2, and as big data-related (“google,” “streetview,” “googleimages,” “camera”) in Group 3 in Figure 3. “Privacy” is visceral and directly lived…and affected by government and private industry.

Figure 3: “Privacy” Related Tags Network on Flickr (1.5 deg)

Google Correlate, soon to be retired, shows that in terms of correlated search terms, “human rights” is conceptualized differently in the U.S. vs. China, for example. (Table 2) The respective focuses are different, in descending order.

|

“Human Rights” in the U.S. |

“Human Rights” in the P.R.C. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Table 2: Google Search Terms Time-Correlated with “Human Rights” as a Search Term in the U.S. vs. China (from Google Correlate)

Interestingly, various human rights frameworks describe “communication rights” as a fundamental right as well. From the advent of the Web, there have been calls for governments to emplace proper laws for the digital age to “ensure markets remain competitive, innovative and open…” and that to “protect people’s rights and freedoms online” (Berners-Lee, 2019, as cited in Kerr, Musiani, & Pohle, 2019, p. 1). These conversations of digital rights are important given the ubiquity of digital in people’s lives (Goggin, Ford, Martin, Webb, Vromen, & Weatherall, 2019). Internet governance to enable human rights involves the following issues (in descending order): “security, access, Internet critical resources, domain name system, privacy, freedom of expression, human rights, multi-stakeholderism (sic), openness, open standards, diversity, intellectual property rights, infrastructure, Internet Governance Forum, IP addresses, multilingualism, public policy, developing countries, content regulation, deliberation, global governance, and others (Padovani, Musiani, & Pavan, 2010, p. 371), to ensure basic functioning and access. One author writes: “If AI developers treat privacy not as an ethical preference but as a fundamental human right, it would strengthen the privacy considerations that already exist in industry norms and technical standards” (Latonero, 2018, p. 13), which does suggest some of the extant guardrails in the information technology space that may guide the onboarding of new technologies. The building in of privacy enablements into technology systems have been defined as including “notice, choice and consent, proximity and locality, anonymity and pseudonymity, security, and access and recourse” (Langheinrich, Sept. 2001, p. 273).

How the technologies are used also have widespread and long-term implications on their usage. In a study across 36 countries, the Internet has had mixed results on “political trust” or citizen confidence in political institutions and their legitimacy. In the face of Internet censorship, political trust is strengthened, but in terms of “violation of user rights,” political trust is weakened (Lu, Qi, & Yu, 2019, p. 1). Given the prevalence of online incivility, online civility (politeness) is sufficiently novel to induce social trust, according to one experimental research study using a social networking platform (Antoci, Bonelli, Paglieri, Reggiani, & Sabatini, 2019, p. 83). Women and younger users have higher levels of expectations for trust online (Warner-Søderholm, Bertsch, Sawe, Lee, Wolfe, Meyer, Engel, & Fatilua, 2018, p. 303), which may have implications for their usage of online spaces. Breakages in trust may turn groups off to participate online. Already, there are drops in the numbers of users on social media, attributed to fatigue. Some “root causes of social media fatigue” include the “stressors of privacy invasion and invasion of life” with personality traits as mediators of this perception (Xiao & Mou, 2019, p. 297). One turnoff is “presenteeism,” defined as “the degree to which social media enables users to be reachable” (Ayyagari, et al., 2011, as cited in Xiao & Mou, 2019, p. 301).

Another study found that citizens perceived an increased sense of control over national government corruption (“misuse of public power for private gain”) with the presence of social media, based on analysis of five years of data from 62 countries (Tang, Chen, Zhou, Warkentin, & Gillenson, 2019, p. 2).

These information and communications technology (ICT) channels have been used for mass disinformation campaigns, in a highly dynamic geopolitical space (Fried & Polyakova, 2018). Others have observed malicious actors have used the Internet to weaponize civil societies to “foment dissent and create breaches along ethnic, racial, religious, and socioeconomic lines” to “intensify hyperpartisanship” (Jayamaha & Matisek, 2019, p. 11), with the 2016 U.S. presidential election cited as one case in point. In the aftermath of the campaign election meddling (including hacking attempts), various social media platforms were critiqued and there were increasing calls for “platform governance” (Gorwa, 2019, p. 854). In an age of “modern transnational terrorism,” state security is pitted against “freedom of press and speech,” with various social media companies liable for “federal criminal prosecution…” for providing “material support to terrorism” by enabling “terrorists and their sympathizers to glorify and pursue their violence on social media” (VanLandingham, 2017, p. 1).

There are spillovers from the cyber into real space and vice versa, known as the cyber-physical confluence. One concern is about the usage of advanced technologies for autonomous warfare (Jensen, Whyte, & Cuomo, 2019), with the harnessing of artificial intelligence and machine learning and automation to create weapons systems that destroy humans, without other humans in the decision making loop. Warfighters have long used social media as part of their information operations (Marcellino, Smith, Paul, & Skrabala, 2017, p. iii), defined as “the integrated employment, during military operations, of IRCs (information-related capabilities) in concert with other lines of operation to influence, disrupt, corrupt, or usurp the decision making of adversaries and potential adversaries while protecting our own” [Joint Publication (JP) 3-13, 2014], as cited in Marcellino, Smith, Paul, & Skrabala, 2017, pp. ix – x].

Citizen Privacy, Human Rights, and Individual and Social Protections vs. Socio-technical Incursions

The focal research questions are the following:

How potent are the temporary pixels and ephemeral voices online in support of transnational advocacy generally and this issue of human (privacy, human rights, individual and social protections) well-being against socio-technical incursions in particular? Why?

The “case” around which this issue is explored is the pursuit of citizen privacy, human rights, and individual and social protections against socio-technical incursions, given the technological advances in the past few decades. The basic interests are to make personal information private from government and industries, in order to preserve people’s personal choice-making and degrees of freedom. This case is represented through mass media coverage along with reams of social imagery and some user-generated videos.

Social imagery. At this moment, the contemporaneous case involves street clashes of Hong Kong citizens and police, with the discontent sparked by the proposal of an extradition policy to have court cases heard on mainland China for some cases originating in Hong Kong. Essentially, many of the citizens of the former British colony (which reverted to Chinese control in 1997) disliked the sense that they were losing many of their prior rights, which they felt were enshrined in an agreement for the handover. The specifics of this issue are not the main focus here. Rather, the demonstrations are contemporaneous, and the issue of socio-technical surveillance is a factor, with many of the demonstrators wearing not only masks for tear gas but also face masks to hide identities. (This case is being used in a generic and semi-abstracted way to look at transnational advocacy. In this sense, the local issues are somewhat less important than that at the larger level—of government reach, of socio-technical surveillance, of the uses of social media and encrypted apps for social organizing, of strategic and tactical social media messaging, and the clash of interests. This is not to take anything away from the seriousness of this issue or the futures of 1.4 billion people and their future generations at stake.)

This event was analyzed based on 1,344 images scraped from Google Images highlighting the multi-month events. The images show people of all generations in the marches, which have brought out a fifth of the city’s population, according to press reports. Residents of a city in transition are warning off their national government against using too heavy a hand on themselves. On one side are demonstrators with Molotov cocktails, masks, messaging, signage, and barricades; on the other side is tear gas, water cannons, police batons, shields, and messaging. There are signs about sovereignty and freedom and resistance to a proposed change to the territory’s laws to enable extradition of those arrested to be tried elsewhere. Some signs protest Communism, the ostensible ruling framework for the mainland. There are protests against a demonstrator blinded during a police action. On social media, there are overhead and on-street images of protesters, carrying flags of the U.S. and Britain (to try to encourage their engagement), and lists of demands. There are counter-demonstrators waving flags of the national government. Will a closer integration spark demands on the mainland for more freedom? Will these actions spark a more forceful mainland government presence? (Figure 4) This issue does not have even a temporary resolution at the moment of this chapter’s submittal.

Figure 4: Social Imagery of a Contemporaneous Challenge-Response (in Hong Kong demonstrations)

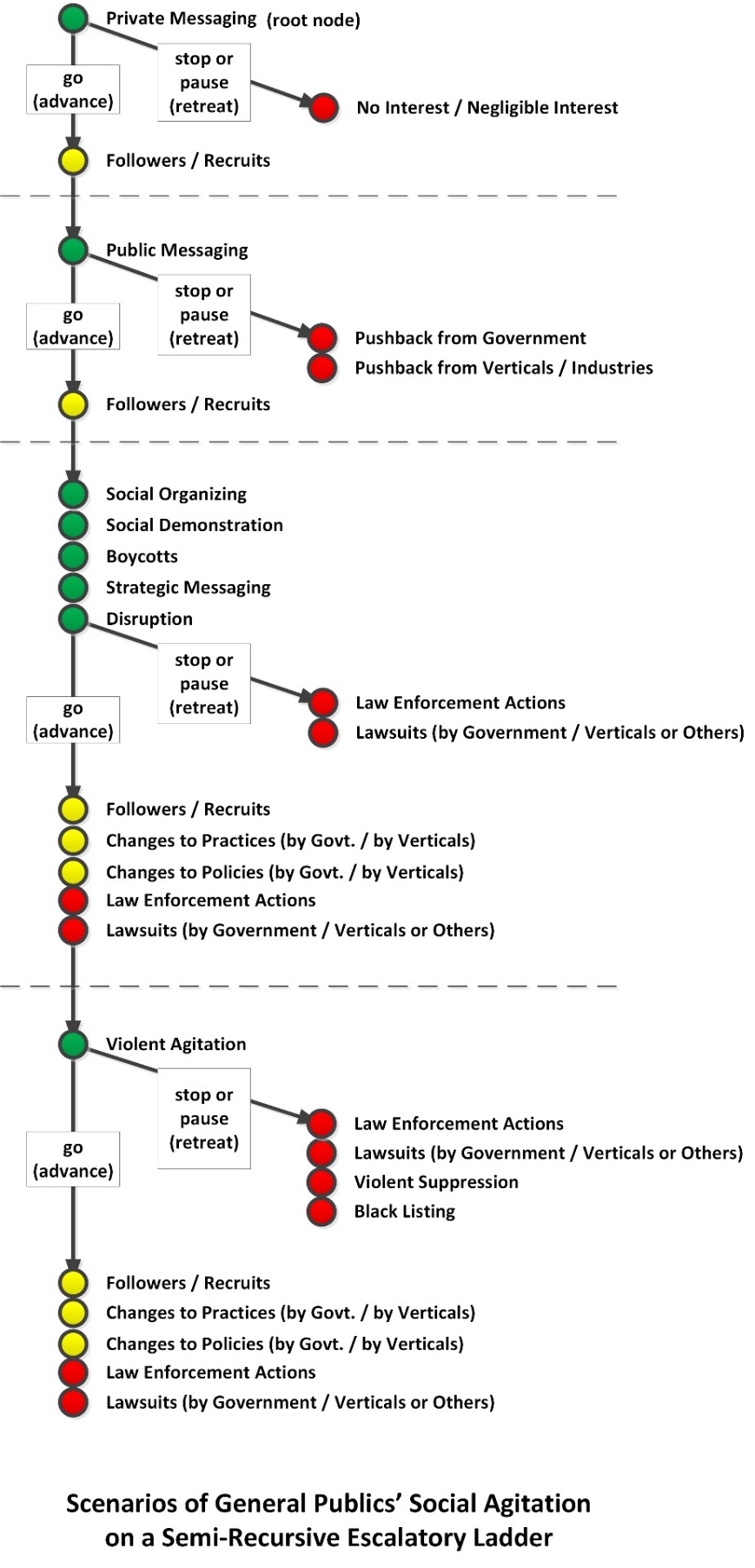

Gamed out. If this issue were gamed out, in a partially explicated game tree, from the point-of-view of the transnational advocates, what would it look like? A game is an expression of strategy and tactics, and it is informed by the respective natures of the game actors, their interests, their levers for making change, and other factors.

A game is specified by the choices or moves available to the players, the order, if any, in which they make those moves, and the payoffs that result from all logically possible combinations of all the players’ choices. (Dixit, Skeath, & Reiley, 2009, 2004, 1999, p. 362)

In game theory, a core idea is that actors in a space choose actions with the maximum expected utility or the highest expected gain (Morrow, 1994, p. 23), with the least cost (efficiency assumption). Each actor—whether an individual or a collective—has different preferences for various actions and payoffs, and with an attendant range of risk acceptance to risk aversion preferences (Morrow, 1994, p. 37). In Figure 5, the main stakeholders at a macro-level sense are introduced along with some observations of their points of leverage or power.

Figure 5: Some Levers for Change among the Actors

A “Nash equilibrium” is a state where no player “has an incentive to deviate unilaterally from its equilibrium strategy” (Morrow, 1994, p. 81). In that state, stated another way, the actor or player has the “utils” or utility fulfilled. These are necessary over-simplifications in these general sketched equilibriums.

For the “general public(s),” they are assumed to be willing to exchange private information for free services based on how many use various social media and Web 2.0 tools. They are willing for government to have their private information as long as it is not misused or leaked. They are willing to give government the benefit of the doubt, especially if they are not aware of what the technological and government capabilities are. Protests involve disagreement with others in public and are effortful and risky.

For the “verticals / industries,” they are going to push the edges of engineering and technological features in order to win market share. However, they also try to work within legal frameworks, so they are not at risk of losing lawsuits and paying out large sums. They are also interested in maintaining good public relations to avoid bad PR and resultant losses in the marketplace. Technological advances are not necessarily deterministic, but they do introduce a forcing function into the environment and require all entities to adjust to them (or to challenge them).

“Government(s)” have an interest in acquiring the highest technological and other capabilities to achieve their responsibilities but in a way constrained by laws and policies. The law enforcement part of government has a legal “monopoly on violence,” and it is in their interests to keep this. Also, there is inherent interest in maintaining government credibility, for their assertions and their actions. There is defense of their purview and active contravening of others’ attempts to co-opt their power. And, they have an interest in maintaining the social contract enabling governance, by provisioning the population writ large, to enable safety, security, social order, the meeting of basic human needs (food, education, housing, healthcare, and so on). In general, governments as human systems bound by rules prefer the status quo and are “conservative” and do not relish challenges to the rules.

Other “entities” have a mix of affordances and constraints, but they generally advocate for their own positions, within financial constraints, legal constraints, leadership limits, membership limits, and other factors.

Each of the stakeholder groups has a sense of an idealized future, and each is generally arguing for what they see as good. (There are malicious actors, too, but in this case, the game assumptions are that each group is benevolent. In the real, there are spoilers who may only have an interest in wrecking others’ systems…but that beyond the scope of this work.) Each entity is jealous and possessive of its own prerogatives, and none will give ground willingly if concessions mean backing off. Basic strategies suggest the following: pursuing goals with the least cost (for efficiency), not contravening values, not forming alliances with untrusted others, not locking in losses (if unavoidable), and so on. Message strategically, in alignment with one’s aims, but be factful where possible. Avoid over-sharing and possibly releasing sensitive information. By actions, it is important to not give up something valuable for something cheap (but pursuing the opposite if possible), not trade away the permanent or long-term for something temporal or short-term, not contradict one’s own values in actions, and so on. A “dominant” strategy is one that stands to deliver effectively, given the context and the other actors; a “dominated” strategy is one that is already a loss, one that stands to result in concessions and backing off of objectives. With sufficient data and observation of extant patterns, some level of predictivity and probabilistic understandings may be brought to bear to understand which strategies are most effective in which contexts, and enabling analyses based on conditional probabilities (like Bayesian analytical approaches, informed by beliefs and “priors”).

Each of the stakeholder groups orientate to each other. Each are at least partially aware of each other. They are assumed to have some overlapping interests and some conflictual interests, so the game is not purely a cooperative or non-cooperative one. A basic partially explicated game tree begins with a temporal equilibrium of status quo. In this case, a sequential bargaining game is assumed. In general, bargaining games launch in the presence of “surplus” or some “excess value” that is available for the bargaining context (Dixit, Skeath, & Reiley, 2009, 2004, 1999, pp. 692 – 693). For the transnational advocacy for privacy, there was a “window of opportunity the NSA scandal offered” (Haunss, 2015, p. 227), in reference to Edward Snowden’s apparent actions releasing secret data from the U.S. National Security Agency. One author asks if this scandal is “the Privacy Chernobyl that has the potential to mobilize mass protests and to galvanize the various privacy advocacy groups into one privacy social movement?” (Haunss, 2015, p. 228) In a sense, some are looking to this historical event to jumpstart a global scale narrative of people’s personal information and how much access anyone would have to it.

Not taking action is always an option, but there are risks to silence and waiting because that moment will pass, and it may not arrive again (and certainly not with the same contextual conditions). The liminality of change can be high-risk because of the bargaining behaviors and also because of where the negotiations end and the fallouts in the systems.

The game tree is explicated visually and narratively but not in a mathematical representation of possible payoffs. A basic assumption is that each of the stakeholder groups has its own interests, but each are willing to create alliances based on points of common interest. It is assumed that changes are made to the status quo all the time but each of the entities, and game changers (from government policy, from new technologies, from changes in public desires, from new leadership, and so on) can arise anytime. A “subgame perfect” game is one in which a desirable end is defined and then the optimized steps are selected at each juncture.

The root node of the game tree begins with private messaging among the nascent transnational advocacy group of individuals with shared values and interests. They either go to public messaging once they have sufficient interest and confidence to advance, or they remain in their private groups and pause or retreat. For those who go public, they attract some supporters and some detractors in that step. Based on feedback, they may choose to advance or pause or retreat. And so on. They may escalate to social organizing and mass actions; they may engage in violent agitation. In all the steps, there are other actors in the space who have their own interests and wills (collectively). (Figure 6) [Different game trees may be drawn for the other stakeholders. A fully explicated game tree would bring in the hands of the respective stakeholders and their actions at each step and define respective payoffs and losses, given the conjointness of game trees.]

Figure 6: Scenarios of General Publics’ Social Agitation on a Semi-Recursive Escalatory Ladder

For some, a pause may be expensive. For example, if demonstrators have attracted a large number of citizens to participate, that is not a grouping they can necessarily easily coalesce again. A pause may mean a loss of momentum and public interest; it may signal weakness. For government, they can play a waiting game because most such large-scale demonstrations devolve into disorder, as people have to return to their daily lives.

The claim of “leaderlessness” among the demonstrator-citizens works against their interests because who is to say that new claims will not suddenly arise after initial sets of demands have been settled? Who is to say that the movement will not become fractious and spin off into other bodies with other interests (as has been observed in other movements)? Who is to say that there are not “hidden hands” using the demonstrators as “cutouts” for others’ (nation-state’s) interests? If there is no authority, then who is responsible? If it is no one, then government is only shadowboxing with a faceless entity that cannot be held to account. Even if the ideas were valid and could benefit the larger context, how it has arisen in a confrontational, angry, broadly public, and fractious way…may make the ideas sufficiently toxic to use. There are redlines that governments cannot cross, and such contexts may make such redlines less likely to be contravened.

If this challenge were modeled as a classic Prisoner’s Dilemma, with Player 1 as the demonstrator-citizens, and Player 2 as the government, the 2×2 payoff matrix could look like the following. (Table 3) If the demonstrator-citizens cooperate, and the government cooperates, there may be a temporary middle ground found, and the larger issues may be rectified or addressed in the future (ideally). The score is (5,5) in this first scenario. If the government defects (resists, does not cooperate with the demonstrator-citizens), and the demonstrator-citizens cooperate, then the demonstrator-citizens lose, and their time spent demonstrating is a sunk cost; the score is (0,8). If the demonstrator-citizens defect, and the government cooperates, then the demonstrator-citizens win their demands, and the government is seen as losing credibility and power; the score is (8,0). If both the demonstrator-citizens defect, then there is a stalemate, and the score is (0,0). Some may ask: Who is keeping score? Well, everyone…because the past informs the future; it sets precedents. If “shared governance” is accepted, then a government loses authority and power, and coercive outcries on the street are validated as a form of governance. Who “blinks first” matters because weaknesses invite more challenge. Giving ground under duress or public pressure reads like a loss and is often treated that way. Whoever is seen to inhabit the moral high ground can make a case to the general public and the watching world…how defensible their position is. Social tolerance for disorder is limited, and the clock is constantly running on the issue.

|

|

Player 2: Government |

||

|

Player 1: Demonstrator-Citizens |

|

cooperate |

defect |

|

cooperate |

(5,5) |

(0,8) |

|

|

defect |

(8,0) |

(0,0) |

|

Table 3: A Prisoner’s Dilemma Payoff Matrix for the Demonstrator-Citizens vs. Government Issue

Bargaining decisions are not necessarily so cleanly spelled out. Perhaps one of the strategies is a game of chicken, to see if the other side can be made to capitulate under pressure. Perhaps a strategy for the demonstrator-citizens is to force the government to show is “iron fist” and how it does not have the citizens’ interests at heart, even at the cost of receiving violence and potential fatalities among their ranks. Perhaps a strategy for the government is to force the hand of the demonstrator-citizens by pushing them to resort to property destruction, hooliganism, and violence, to delegitimize them: Are these the people that you want to have changing up laws of the land and in this manner? Such pressure tactics are to force the other side’s “real face,” whatever that may be. These respective narratives play to a broad audience. Each side is engaging in social performance in that collective moment. An empath’s view of the context, at macro level, may enable the teasing out of interests and strategic messaging and bargaining positions and may benefit petitions for change and challenges to power.

In the real world, human restiveness is a constant and a given. Human roles shift and change, and people’s identities may exist across the board of various stakeholders to an issue. Chance factors are constantly at play. Predictivity even on small things can be difficult. Here, events do not unfold in a step-by-step way. Multiple actions may be ongoing. Random chance affects anywhere in the game tree (Dixit, Skeath, & Reiley, 2009, 2004, 1999, p. 49); chance factors present surprises to all players. Some actions are permanent and irretrievable; others are temporary, with possible “takebacks.” The first are signs of “costly signaling,” and the latter are forms of “cheap talk” (aka “babbling”) which may help define the environment around which negotiations are occurring but are also not fully credible (because of the cheapness of the talk). Additional leverage may be harnessed by the general public by disrupting the lives of others in the society or showing up the government as not being in control. There are risks of over-reach, of demonstrators to violence, or governments to excessive violence and other ignominy. In terms of the call-and-response dynamic, certainly, the government and other entities may choose to respond minimally or even with occasional silence, based on their strategic aims. Too much call-and-response, the responding entities are giving power over to those putting out calls (the demonstrators). Concessionary moves may end a protest, or they may encourage heightened demands (while the going is good). Each side is walking a high wire act.

Discussion

The basic focal research questions were the following:

How potent are the temporary pixels and ephemeral voices online in support of transnational advocacy generally and this issue of human (privacy, human rights, individual and social protections) well-being against socio-technical incursions in particular? Why?.

The power of pixels and ephemeral voices depends on the context, the stakeholders, what is asked of the stakeholders, and other factors. Alone, pixels and electronic voices are not particularly inherently potent. As for human privacy, per the research, there has been some headway in government policies, government-instigated lawsuits, commercial practices, and others efforts. However, there have also been advances in the capabilities of government to conduct necessary surveillance, in engineering advancements enabling further incursions into people’s lives, and so on. It is difficult to provide an accurate “on balance” analysis because the space is so dynamic. Also, with known unknowns, it is difficult to quantify the respective risks of malign and intrusive government social controls. Some researchers argue that social controls are not necessarily “malignant and anti-democratic” but can be benign and part of “a democratic endeavor” and part of human rights (Sarikakis, Korbiel, & Mantovaneli, 2018, p. 275). The co-authors argue that social actors need to be responsible for social change, and the focus should be on human relations not on the “’technological object’—whether machine or code, symbols or even bureaucracy” because what is actually at stake are “social relations” affected by “information generally, personal data and privacy more specifically” (Sarikakis, Korbiel, & Mantovaneli, 2018, p. 287). The new technologies may be harnessed by the marginalized and dispossessed to document “police violence…war crimes at scale…environmental pollution…” and so be a positive force for “grassroots documentation of abuses” to advance human rights (Gregory, 2019, p. 374). How the technologies are wielded are an important aspect of their value for human rights. An earlier work made the case about using online communications for “attracting support, coordinating action, and disseminating alternatives” for addressing “transnational action, leaderlessness, profusion of concerns, tactical schisms, and digital/language divides” (Clark & Themudo, 2006, p. 50) for “dotcauses” or Internet-based political networks “which mobilize support for social causes primarily (but not necessarily exclusively) through the Internet” (Clark & Themudo, 2006, p. 52). Civil societies may engage in various forms of “virtual mobilization” (Clark & Themudo, 2006, p. 52). Web 2.0 technologies, including “social networking sites, blogs, podcasts and wikis,” may be harnessed to “coordinate, synchronize and document campaigns” as a complement to more traditional means of social organization (Pillay, 2012, p. vi). Said another way: New “…digital media are helping people self-organize and coordiante massive protests in the absence of formal organizations” (González-Bailón, 2015, p. 512), potentially enabling efficiencies of organization, including reach and speed, for collective actions, and new forms of protest including cyberattacks like DDOS attacks and hacking and increasing sophistication. Most of what occurs online is in clear text and readable by others. Certainly it is not unheard of for people to lose their jobs for social media postings (Parker, Marasi, James, & Wall, 2019), much less than for marching against their own government.

This is not to say that there has not been advancement on the privacy protection front. Private citizens have applied “inventive strategies …to subvert, distort, block and avoid surveillance (Marx, 2003, as cited in Bennett, 2012, p. 412).There are government authorities working to ensure “privacy and data protection” (Bennett, 2012, p. 412). In Europe, consumers now have a “right to be forgotten.” Actions by the UN General Assembly in 2013 and 2014 codified “surveillance as a human rights problem” (Haunss, 2015, p. 230). The U.S. government has made changes to some of its collection of data of its own citizens, and some private data are held now by companies and not directly by the government. Citizens’ rights are protected against surveillance unless there is concern of possible crimes being committed, so while information is collected, it generally cannot be accessed without legal cover. “Social credits” may be advanced in one country currently, with people’s digital doppelgangers being examined for compliance, but in many other locales, governments profile citizenry based on their records. Governments all keep their secrets about what is knowable and by what methods and how their various tools are used, to enact the responsibilities of governance (including law enforcement, security, taxation, and other aspects). Those in government are also citizens, too, and with awareness, perhaps they can try to ensure that excessive power is not in the hands of government. (Ironically, this concept seems to have salience in the U.S. only and not among other polities. Also, even with such ideas, many people acquiesce to power, even against the dictates of professional ethics and morals.)

About naivete and transnational advocacy online. A naïve approach to transnational advocacy may be the assumption that hard problems are easily solvable or that if sufficient attention is on it that the problems will solve by publicizing the issue (public attention ≠ change). In some cases, attention may reinforce efforts and strengthen endeavors; however, in other cases, the attention may dissipate that energy via catharsis and something of the “screen effect” (where expressing an idea feels like action was taken when nothing really changed except for the messaging). This is a version of the reinforcement vs. catharsis argument in media studies; here, for some, messaging on social media reinforces convictions and may make actions more likely; for some, expression online results in a dissipation of the energy, and no actions are taken. Social ripples splash and then dissipate and are often forgotten, with some new outrage arising predictably. Awareness does not usually translate into actions. A social media posting is often just one voice in a wilderness of voices, including those of cyborgs (humans and robots within a social media account) and robots (scripts that create and disseminate messaging).

At core, to make change, there has to be awareness, sense of salience, care (vs. apathy), commitment, measurable actions, accountability, incentives, encouragement, and other aspects. Perhaps a confluence of factors have to occur to advance an issue; rarely is it one thing alone that is determinative or decisive. Changes may have to be institutionalized into the legal system, the political system, the social norms and culture, and they have to be taught to future generations. What may be of great concern to one generation may not carry over to the next. Some changes occur subtly and quietly, over time, and even below the level of collective awareness.

In general, people cannot be expected to act against their own perceived interests. In a context with competing interests, those with the most powerful voices and resources and power are expected to prevail. Another idea is that the current state-of-the-world is arrived at based on powerful socio-cultural and historical forces and present-day interests. People do not give up power easily or without rigorous defenses. Kurt Lewin proposed that change requires an unfreezing-change-freezing process to enable change in his three-step model in the 1940s, which may apply here. Societies do not change swiftly. One observer observed that “…every society has its own carrying capacity for making change…” (Mattis & West, 2019, p. 222). Making change is effortful against inertial forces and interests. Change seems to happen in fits and starts, in the way that “punctuated equilibrium” has been described. The “klieg lights” of attention do not alone make change, but they may influence those with power to advance particular agendas or support particular positions. Some researchers offer a sense of transnational advocacy networks having various influences on power, as stages:

(1) issue creation and attention/agenda setting;

(2) influence on discursive positions of states and regional and international organizations;

(3) influence on institutional procedures;

(4) influence on policy change in ‘target actors’ which may be states, international or regional organizations, or private actors…;

(5) influence on state behaviour. (Keck & Sikkink, 1999, p. 98)

The stages seem to be ascending and cumulative. There seems to be a necessary investment of longitudinal time.

In virtually every confrontation, there are informational asymmetries; each side lacks critical information in part because not everything is known or is available. Then, too, cognitive biases suggest that different individuals and groups focus on particular information and neglect others. User opinions tend to correlate with “the sentiment of the news post and the type of information source” (Kumar, Nagalla, Marwah, & Singh, 2018, p. 42), for example. What is “ground truth” may not be perceivable. Oftentimes, with the complexity of human systems, it is difficult to understand the particular historical moment. Serendipity and chance are always at play. At various times, the various interacting systems and dynamics focus on individuals, who may play critical roles in history, but these may not be clear until sometime in the future, with individuals looking retroactively. Then, too, in the intensity of the moment, many may imagine themselves on the cusps of historical change, in a heady sense, when the moment is not ripe. Or the leadership is not sufficiently telegenic or charismatic. Or decisions drive a movement into missteps and erroneous choices. Or rumors may be insufficiently vetted, in a time of the post-truth era and #fakenews, and bad information misleads the leadership and membership. Even without so much environmental noise, people are susceptible to irrationalities and cognitive biases and errors in judgment, and misunderstandings of governance and technology are rife. Some advances in this space include “bots, voice assistants, automated (fake) news generation, content moderation and filtering” which affect digital communication (Gollatz, Beer, & Katzenbach, 2018 – 2019, p. 1).

Some “leaderless” movements may indeed be without leadership and without articulated direction. Perhaps the messaging itself may not be sufficiently coherent. Or the followers attracted to a particular movement do not take actions to actually advance the cause. Mass demonstrations may be noticed in real time by some (because such out-of-channel activism is sufficiently anomalous to be noticed) but forgotten in time, potentially as a piece of political theatre. Movements may be catalysts and spark awareness and interest, but unless the message gains traction among a larger receptive audience, change itself often takes much effort and inputs and resources. To make change that is persistent and real, there often have to be actual disciplined commitments and investments to create and maintain. In the world, there are historical examples of slow progress on very critical issues, like environmental change or diplomacy to resolve issues, with only very small-step incremental changes. Even if there is consensus that change is needed, most serious issues still require many decades to achieve. With so many actors at play simultaneously, various dynamics make a future, which is not particularly predictable.

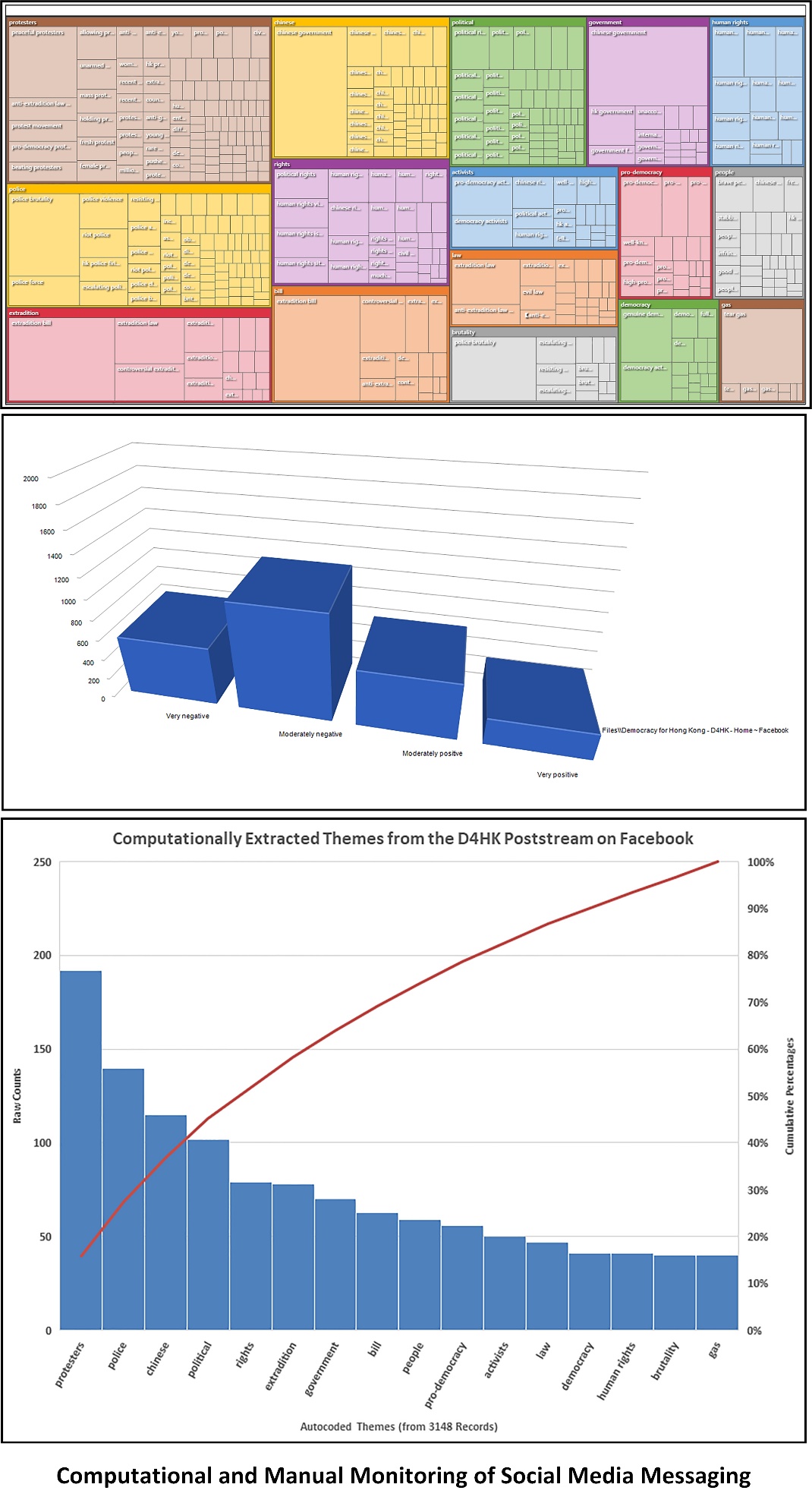

Social Media and Effective Transnational Advocacy: Some Basics (A Sidebar)Based on this work, some basic tenets seem initially supportable: (1) About people… Select social media platforms where the respective audiences of interest congregate. This will make it easier to find alignments with other groups and the pool information and other resources, to coordinate, and to make common cause. Communicate with the audience members in a way that your message will be heard. Conduct analysis of others’ values, both public and private, in order not to contravene them. Maintain supporter loyalty. Affirm followers online and regularly (but without being irritating), so there is not interest in “defecting” or spinning off into splinter groups. Enable the messaging to be socially inclusive, in the way that franchises enable local adaptations. Movements like the protection of human privacy against socio-technical incursions instantiate differently in different locales based on local concerns. Some amount of “strategic ambiguity” without cultural or geographical dominance may enable an idea to spread further and to encourage higher levels of uptake. Not addressing potentially controversial issues may encourage a broader range of follower-ship because of the uninformed assumptions of the followers about the beliefs of the organizations and leadership. (Said another way: Stated opinions may provoke disagreement and alienation.) Let locals (wherever they are) fill in the blank. In other cases, it may be important not to dissipate energy and impetuses too far. In these cases, geographical location and local particulars may have to carry the day. It is important to know what is energizing the crowds. Strive for early wins and achievements. Participants tend to develop more investment in a movement that is seen to have achieved early wins. Focus on what is practically doable, and do not ask for the impossible. Enable win-win approaches to increase the likelihood of making change. Offer real advances to real problems, not just self-serving messaging. Offer value. (2) About movement identity…and real reasons to make change… Have a clear purpose and a platform and a strategy. Have clear leadership, even if they are working from the background in a “leaderless” movement. (Rule by crowds or the “mobs” does not have a great historical reputation.) Message on social media platforms in a consistent way, with one voice, where possible. Contradictions will be observed and noted, given participant interest and the culture of online communities. Use social media to be transparent, with credible messaging. Control who has access to the formal channels, to control against mis-messaging and spoofing and hijacking. Clean out faux data from channels. Avoid manipulations by outside forces who may want to free-ride the transnational advocacy movement. Avoid other-deception and self-deception as an organization and membership. Align rhetoric and actions. To be effective, a movement benefits from maintaining aligned rhetoric and actions. This is not to lock the movement into stasis and nonchange, but it is to communicate a clear message at any time. Use both the “public” and “private” channels available online. Use each strategically. Maintain a sense of vision and idealism in the work. Vet all information before it goes public. Do not break laws in sharing information. Do not contravene privacy. Do not foment violence. Use private channels when strategizing. Talk to decision makers. Do not assume that private channels are private from government, which have computational and other decryption capabilities. Every message has a range of audience members, some supportive, some not. Assume that cyber is one of the most surveilled “spaces” on Earth. Assume that both computational and manual means of surveillance are applied. Some light computational analyses are shown of the Democracy 4 Hong Kong (D4HK) at https://www.facebook.com/DemocracyForHongKong/. (Figure 7) Be recognizable in the space. Have a clear name for mass media (like “umbrella movement” in this studied case). Have clear visuals that may serve as the logo. Have clear uniforms (“black shirts” in this studied case). Have a clear #hashtag or a few for the movement. Enable continuing conversations on microblogging platforms, for example. (3) About the technologies… Do not conflate “likes” and thumbs-up and kudos with…actual opinions, actual action, actual support, actual resources, or real change. Impressions are only impressions. A selfie is not an accurate or objective portrait, but it is a self-expression. A walk down a street in summer heat is not commitment to real change. Real change will require committed hard work over time. Social media enable a sense of ease-of-change, which is illusory. |

Figure 7: Computational and Manual Monitoring of Social Media Messaging

Future Research Directions

This work asks the question of how to learn from the world and understandings of various systems and humanity and to use electronic communications systems and other tools to foment transnational change. What are compelling “narratives of change” (Wittmayer, Backhaus, Avelino, Pel, Strasser, Kunze, & Zuijderwijk, 2019) that may spark followership and interest (and ultimately, social change at the societal level)? Are there compelling ways to share ideas for social change into the public sphere, where people engage discursively? And are there ways to defend ideas against squelching? What are effective ways to message and to argue for the ethics and outcomes of particular approaches? To communicate with clarity? To organize socially and care about the membership? To engage with other stakeholders constructively? What are optimal ways to leverage social media and Web 2.0 for transnational advocacy, for constructive and prosocial outcomes (and limited externalities)?

How would other versions of the simplified and parsimonious game tree be depicted, with fuller explication and quantified payoffs? What are ways to make respective game trees more accurate to the world? How would this tree be updated to future contexts? How can it be distilled further?

Conclusion

The analysis is a simple (perhaps simplified) one: Will the interests of a nation-state disappear because a (technical) minority of citizenry is asking for that government to give up authority and appointed responsibility? Will government affirm the power of the street when it has not done so in the past and ended prior mass demonstrations in blood? Will it dignify negotiations outside its own political and legal system and possibly encourage future disruptive taking-to-the-street for grievances and petitions? Will it do so outside its own social norms? If current decisions are always made in the “shadow of the future,” what does that portend for this particular context?

If this confrontation ends in constructive change, how so, and by whose point of view? Can a skilled leadership pull out a win-win from this without ceding power and increase trust in government and in citizenry? Can further violence, with its own dark dynamics, be avoided? Or will the limits of leadership and the dark pull of history resolve this in lost life years and potential?

On the one hand, these images evoke a sense of temporal power and hope; on the other, these messages on social media feel ephemeral and already receding into the past, like wind carrying away human voices, to the fast evaporating past, and not to a high stakes future.

What is the power of temporary pixels and ephemeral voices, drowned out by robots and cyborgs, manipulated by governments, filtered by algorithms? How much can be organized on social media with so many different audiences with so many different interests and values? Can these fleeting pixels and faraway voices instantiate permanent and long-term constructive change as soft power influences in a context of transnational advocacy? Essentially, can the voices convince decision makers to change their points of view and commit to hard actions over time into the flowing future, where past is prologue?

Afternote

The author was serving abroad as a professor at a university in the People’s Republic of China when the pro-democracy movement broke out across the nation on June 4, 1989. The demonstrations were put down violently in a military action known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, with an estimated many thousands killed and the event documented by photographers and others. The official government word is that the event never happened. The author accidentally brought a copy of a book with images of the event on her return to a different university in the PRC a few years after, and the book was quietly burned, page by page, along with several other books (by sinologists in the West) deemed too politically sensitive to have on Chinese soil.

In a more recent work, one author writes of the event in retrospect (and with the wisdom of 20/20 hindsight):

During the predawn hours of June 4, 1989, on government orders, 200,000 troops surrounded Beijing, China’s capital, and then marched to its heart. The government’s tanks and armored vehicles cleared the way, crushing the barricades, firing into the crowd, mowing human beings down like weeds. Sanctioned at the very top, the massacre they committed in and around Tiananmen Square—against overwhelmingly nonviolent protesters from all walks of life—shocked the world…Thirty years later the regime that committed the massacre is still in power. (Yiwu, 2012, p. 7)

People live in and of history in every moment, and in and of statistical probabilities. Some generations may learn the lessons from old, and some leaders may learn the lessons from old. Or not. As individuals and as groups, people engage in forgetting, convenient and selective memory. Each new generation starts the clock again in making their own lives and contributing to those of others, and they may expand or contract the possible in different directions. Historical moments do seem to have some degree of repetition, some variations on a theme. Perhaps a future that involves some constructive middle ways will be possible.

And then, just as this work was about to go to press, there was news of the discovery of the SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, in the P.R.C. in December 2019. In the next few months, the infection spread around the world to all the continents except Antarctica. During this outbreak, a variety of surveillance technologies have been deployed: drones, CCTV, social media, mobile devices, AI, facial recognition technologies, and others. Special applications have been created especially for this moment, to achieve various aims, such as notifying people that they may have come into physical proximity with a person with known COVID-19, and others. This pandemic has enabled further incursions into people’s private lives, in the P.R.C., at minimum. There are fears that such incursions will remain, long after the pandemic resolves (one way or another).

Dedication

This work is dedicated to my former students in the P.R.C. and the U.S., with great respect and affection and the highest hopes for their bright futures… We are all co-creating our collective futures simultaneously, with an abundance of awareness and knowledge. There is a balance here somewhere which enables the respective human needs to be met with the greatest individual latitude possible.

References

Antoci, A., Bonelli, L., Paglieri, F., Reggiani, T., & Sabatini, F. (2019). Civility and trust in social media. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 160, 83 – 99.

Bennett, C. J. (2012). Privacy advocates, privacy advocacy and the surveillance society. 2012). Routledge handbook of surveillance studies. London: Routledge, 412-419.

Clark, J.D., & Themudo, N.S. (2006). Linking the Web and the street: Internet-based ‘dotcauses’ and the ‘anti-globalization’ movement. World Development, 34(1), 50 – 74.

Degli Esposti, S. (2014). When big data meets dataveillance: The hidden side of analytics. Surveillance & Society, 12(2), 209-225.

Dinev, T., Hart, P., & Mullen, M.R. (2008). Internet privacy concerns and beliefs about government surveillance – An empirical investigation. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 17(2008), 214 – 233.

Dixit, A., Skeath, S., & Reiley, D. (2009, 2004, 1999). Games of Strategy. 3rd Ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Fried, D., & Polyakova, A. (2018). Democratic defense against disinformation. Washington, DC: Atlantic Council. 1 – 16.

Friedman, M. (2016). Pumpkinflowers: A Soldier’s Story. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books.

Goggin, G., Ford, M., Martin, F., Webb, A., Vromen, A., & Weatherall, K. (2018). Digital Rights in Asia: Rethinking Regional and International Agenda.

Gollatz, K., Beer, F., & Katzenbach, C. (2018). The turn to artificial intelligence in governing communication online.

González-Bailón, S. (2015). Social Protest and New Media. Elsevier. 512 – 517.

Gorwa, R. (2019). What is platform governance?. Information, Communication & Society, 22(6), 854-871.

Gregory, S. (2019). Cameras everywhere revisited: How digital technologies and social media aid and inhibit human rights documentation and advocacy. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 11, 373 – 392.

Hai-Jew, S. (2019). Action potentials: Extrapolating an ideology from the Anonymous Hacker Socio-Political Movement (a qualitative meta-analysis). Ch. 5. In C. Akrivopoulou’s Digital Democracy and the Impact of Technology on Governance and Politics: New Globalized Practices. Hershey, Pennsylvania: IGI Global.

Hai-Jew, S. (2019). Electronic Hive Minds on Social Media: Emerging Research and Opportunities. Hershey: IGI Global.

Haunss, S. (2015). Privacy activism after Snowden: Advocacy networks or protest. Fritz, Karsten/Harju, Harju (Hg.): Cultures of Privacy–Paradigms, Transformations, Contestations. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, 227-244.

“Human Rights.” (2019). United Nations. Retrieved Sept. 15, 2019, from https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/human-rights/index.html.

Jayamaha, B. B., & Matisek, J. (2018). Social Media Warriors: Leveraging a New Battlespace. Parameters, 48(4), 11-23.

Jensen, B.M., Whyte, C., & Cuomo, S. (2019). Algorithms at war: The promise, peril, ad limits of artificial intelligence. International Studies Review, 0, 1 – 25.

Keck, M. E., & Sikkink, K. (1999). Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics. International Social Science Journal, 51(159), 89-101.

Kerr, A., Musiani, F., & Pohle, J. (2019). Communication and internet policy: A critical rights-based history and future. Internet Policy Review, 8(1), 1 – 16.

Kumar, N., Nagalla, R., Marwah, T., & Singh, M. (2018). Sentiment dynamics in social media news channels. Online Social Networks and Media, 8, 42 – 54.

Langheinrich, M. (2001, September). Privacy by design—principles of privacy-aware ubiquitous systems. In International conference on Ubiquitous Computing (pp. 273-291). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Latonero, M. (2018). Governing Artificial Intelligence: Upholding Human Rights & Dignity. Data & Society, October. 1 – 37.

Lehoucq, E., & Tarrow, S. (n.d.) The Rise of a Transnational Movement to Protect Privacy.

Lu, J., Qi, L., & Yu, X. (2019). Political trust in the internet context: A comparative study in 36 countries. Government Information Quarterly. 1 – 10. Article in press.

Marcellino, W., Smith, M.L., Paul, C., & Skrabala, L. (2017). Monitoring Social Media: Lessons for Future Department of Defense Social Media Analysis in Support of Information Operations. Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation.

Marris, J., & West, B. (2019). Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead. New York: Random House.

Morrow, J.D. (1994). Game Theory for Political Scientists. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Padovani, C., Musiani, F., & Pavan, E. (2010). Investigating evolving discourses on human rights in the digital age. International Communication Gazette, 72(4-5), 359-378.

Pillay, K. J. (2015). Do Web 2.0 social media impact transnational social advocacy?: a study of South African civil society and Greenpeace (Doctoral dissertation).

Parker, J.M., Marasi, S., James, K.W., & Wall, A. (2019). Should employees be ‘dooced’ for a social media post? The role of social media marketing governance. Journal of Business Research, 103, 1 – 9.

Sarikakis, K., Korbiel, I., & Piassaroli Mantovaneli, W. (2018). Social control and the institutionalization of human rights as an ethical framework for media and ICT corporations. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 16(3), 275-289.

Tang, Z., Chen, L., Zhou, Z., Warkentin, M., & Gillenson, M. L. (2019). The effects of social media use on control of corruption and moderating role of cultural tightness-looseness. Government Information Quarterly. 1 – 9. Article in press.

VanLandingham, R. E. (2017). Jailing the twitter bird: Social media, material support to terrorism, and muzzling the modern press. Cardozo Law Review, 39(1), 1-58.

Warner-Søderholm, G., Bertsch, A., Sawe, E., Lee, D., Wolfe, T., Meyer, J., Engel, J., & Fatilua, U.N. (2018). Who trusts social media? Computers in Human Behavior, 81, 303 – 315.

Wittmayer, J. M., Backhaus, J., Avelino, F., Pel, B., Strasser, T., Kunze, I., & Zuijderwijk, L. (2019). Narratives of change: How social innovation initiatives construct societal transformation. Futures, 112, 102433.

Xiao, L., & Mou, J. (2019). Social media fatigue – Technological antecedents and the moderating roles of personality traits: The case of WeChat. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 297 – 310.

Yiwu, L. (2012). Bullets and Opium: Real-life Stories of China after the Tiananmen Square Massacre. New York: Atria.

Key Terms

Dataveillance: The “systematic monitoring of people or groups, by means of personal data systems in order to regulate or govern their behavior” (Esposti, 2014, p. 209)

Game Theory: Expression of strategic analysis, usually with mathematical bases

Presenteeism: How accessible people are on social media

Privacy: The protection of personal information against unauthorized access and / or misuse

Transnational Advocacy: The support of a particular position or sense of the world for an issue extending across national boundaries

Transnational Advocacy Network: A group of interconnected actors with shared values working towards the achievement of shared policy outcomes