5 In Flames, In Violence, In Reverence: Physical Protest Effigies in Global and Transnational Politics from a Social Imageset

Shalin Hai-Jew

AbstractThe popularization of the Internet, the WWW, and social media, has enabled various populations around the world to be politically “woke” together, with varying levels of agreements and disagreements around a variety of issues, with conservatism around some and radicalism around others (generically speaking). In social imagery, there are visuals of various protest effigies, depictions of public figures representing certain values, ideologies, platforms, policies, attitudes, styles, stances on issues, and other aspects of the political space. In some cases, the political figures are stand-ins and stereotypes that may represent undesirable change and a sense of threat. The study of physical “effigy” in social imagery from Google Images may shed some light on the state of global and transnational protest politics in real space and the practice of using physical protest effigies to publicize social messages, attract allies, change conversations in the macro political space, to foment social change.

|

Key Words

Physical Protest Effigy, Political Protest, Global Politics, Transnational Politics, Social Imageset

Introduction

Generally, an “effigy” is a model of a person, something created from the human form, “artfully” or not. In a political sense, it is “a roughly made model of a particular person, made in order to be damaged or destroyed as a protest or expression of anger” (“effigy,” 2019). In a pop culture sense, such as in video games, an effigy may be imbued with magical or other powers. On social media, there are a number of images of various physical effigies used in socio-political demonstrations, with public messaging. (These, while in digital form at the point of analysis, originated as physical objects, not digitally born ones.) The public-facing aspects of demonstrations mean that these are often captured in visuals shared on mass media sites and on social media ones.

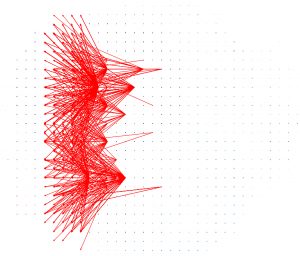

Based on a social imageset of “effigies,” with the political set separated out from others (like photos of historical relics and effigy mounds, like pop-culture ones related to games and music), a number of questions were explored to better understand the uses of physical effigies in global and transnational protest and demonstration. To be clear, “effigies” are used in various ways beyond the socio-political. In the Google Books Ngram Viewer, there are many more references to “effigies” than the other common use of “burning in effigy” phrase (often related to public demonstrations). (Figure 1) This search was done in books published in English from 1800 – 2000. Note that the “burning in effigy” is low on the x-axis. The first reference to “effigy” in English stems from 1539 and is thought to come from the Latin term “effigies” or representations (“Effigy,” Nov. 14, 2019).

Figure 1: “effigy” and “burning in effigy” in the Google Books Ngram Viewer

In a historical sense, an effigy may refer to “recumbent” statues, “funerary art,” and other representations (“Effigy,” Nov. 14, 2019). In the political form, effigies “are damaged, destroyed or paraded in order to harm the person represented by magical means, or merely to mock or insult them or their memory,” with burning in effigy also used for protest (“Effigy,” Nov. 14, 2019). An “effigy mound” refers to “a raised pile of earth built in the shape of a stylized animal, symbol, human, or other figure and generally containing one or more human burials” (“Effigy mound,” July 30, 2019).

In a theoretical work from the 1960s, one author describes an “effigy” as a human-created object made for other humans because of its representational value. He writes:

If pictures consisted only of canvas and colored pigments, paper and daubs, how could a few pencil scrawls, i.e., thinly dispersed deposits of graphite, change a sheet of paper into a drawing, a picture? If pictures are immaterial figurations, how is it that they can be seen? If they are material things, how can they stand for other things, and yet differ from the things they stand for? Pictures are artificial even when they are not artistic human productions. Only man is in a position to understand the pictures of his own making as effigies. For a dog or horse a photograph is something entirely neutral; for man, to the contrary, it is both a something of paper and an effigy which, according to the theme represented, can touch, move, or emotionally shake him. (Straus, 1965, p. 672)

The power of the effigy, in part, stems from its effect on other human viewers, who may be emotionally and cognitively affected. This work also suggests that reference objects, like photographs, can be used to represent a person in effigy, and the in-world uses of people’s photos (in publications and from other sources) have appeared as representations of the individual and / or the bureaucracy or industry that they are a part of. Drawings, illustrations, and cartoon depictions of people may also be human models and effigies and treated in particular ways based on the ideas of the artist, the visual editor, the publisher, and others who are in the chain-of-production for that visual.

In an applied sense, an effigy may be created to speak not only to supporters of the political effort but also those who are undecided and even those who are antagonistic. For some, there may be the sense of the added power of ceremonial objects, something with historic shamanic evocations. However, in general, contemporaneous effigies in the West seem to be more about direct action for social change than trying to harness magic. (In other parts of the world, the tie to folk magic practices remain, as referenced later.) Protest effigies tend to be generally separated from the underlying word referent in a historical sense.

Exploratory research questions

The research questions surround the various personages depicted, what the effigies say about the demonstrators’ shared identities, the physical materials used in the construct of protest effigies, the various types of attacks (and other non-aggressive actions) on protest effigies, some political dialogues occurring around protest effigies currently, and global and transnational issues that are animating for people. The questions are the following:

1. Real-Life Personages

- Which global leaders and other personages attract the most lightning rod sorts of attention? Why?

- What are the most common personal attacks in persons represented in protest effigies? How is their dignity attacked? Their personhood? How are political leaders punished for their stances and representation contrary to the desires of the dissenters?

- How are political effigies styled? What messages does the styling evoke?

2. About Demonstrators

- Who is being appealed to with the physical effigies and political messaging? What value is being offered in the particular collective groups, and why? Who is being left out in the messaging, and why? (If blame is being apportioned, who is being blamed?)

- How does the effigy help create the identity of the demonstrators, who stand against the effigy as other / or who stand with the effigy as the same?

3. Physical Materials for the Construct of Protest Effigies

- What are the most common analog materials used to create effigies?

- How are protest effigies presented in physical space?

- How are physical protest effigies presented in social digital spaces in two-dimensional imagery?

- How are effigies re-used transnationally (if any)?

- How do still social imagery of political effigies compare to social videos available (on YouTube)?

4. Actual and Symbolic Treatment on the Protest Effigies

- What are some common ways that protest effigies are attacked? Verbally? Physically? And others?

- What are some non-aggressive ways in which protest effigies are treated?

5. Political Dialogue and Protest Effigies

- How are protest effigies a part of political dialogue?

- Based on the proliferation of social imagery on formal mass media and on informal social media, what sorts of power do contemporaneous political effigies evoke? How?

- Do contemporaneous modern-day effigies have ties to prior ones, used culturally and ritually? What are some senses of the magical uses of effigies to call up magical powers?

6. Global and Transnational Issues

- According to reverse imagery searches online, in a global sense, what are the main issues being protested in political effigy through social imagery?

- What parts of the world are the locales of the most political effigy-based expression in social imagery? Why might these be so?

- How do various governments respond to political effigies, and why? (In some countries, public protests are precluded by law, and demonstrators put themselves at great risk of harm when they engage in such activities.)

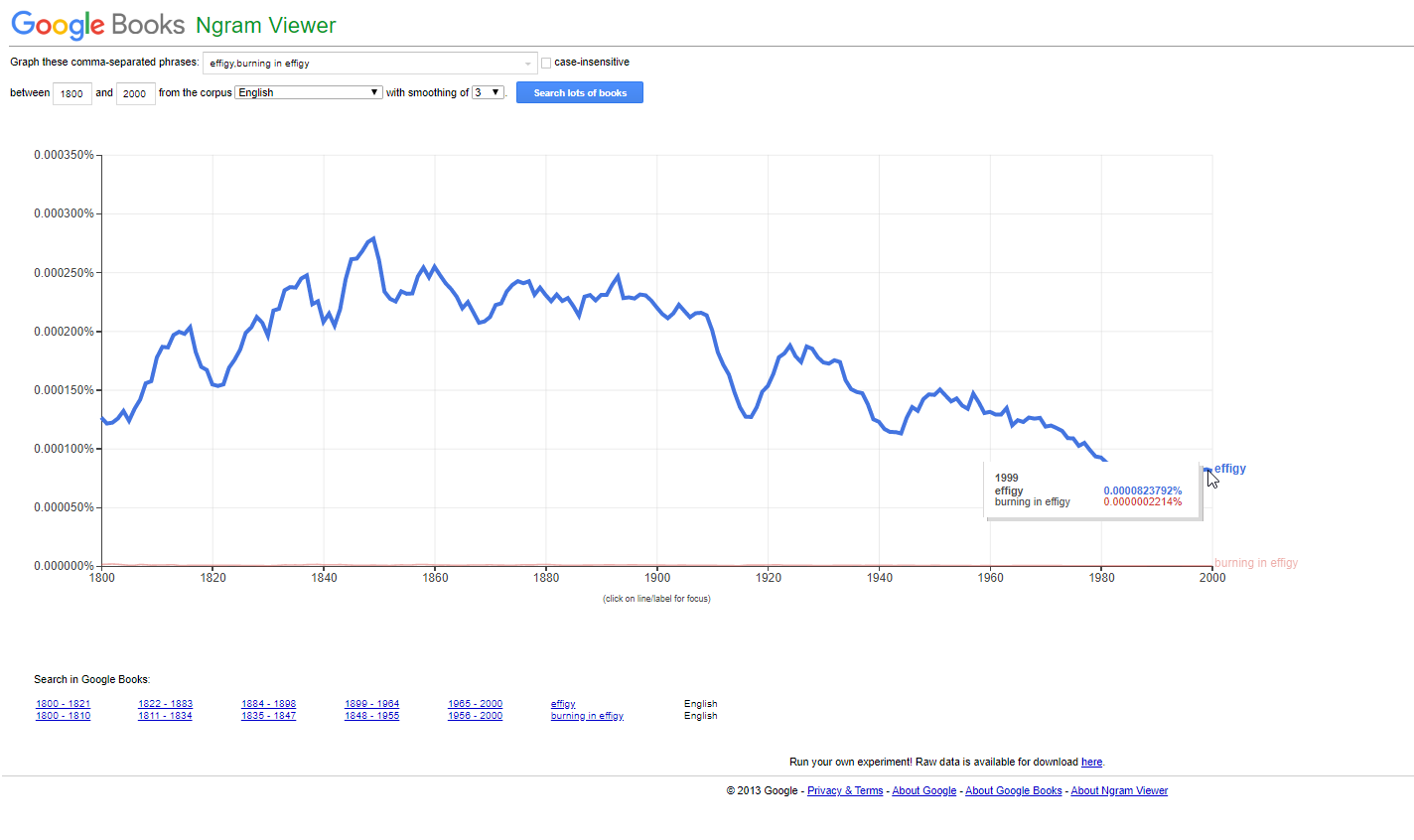

Physical demonstrations, based in physical space, may be local issues. On mass media and social media, they may find resonance on the national, transnational, and global levels. The broad reach of social media, the WWW, and the Internet enable potentially global-scale interest in local issues. (Figure 2) People are at once local, national, and global citizens; in other sense, they may be members of transnational memberships (such as for professional organizations, non-governmental organizations, and others). This broad reach requires people to act responsibly as global citizens in terms of messaging (Panetta, 2015), particularly around issues where there are high emotions (such as around senses of injustice and contravention of global values) and calls for action (messages that can activate people’s behaviors). Even though issues may be local, they may spark far outsized responses through mass communications and social media technologies. Mass empathies may inform message resonance as people engage with each other in disembodied and borderless ways. As such, physical effigies enable meaning making across cultures with their pseudo-embodied messaging, by depicting persons who stand-in for particular values and practices and policies. The influential role of the human imagination makes distant issues seem locally relevant. In a smaller world, interconnected by trade, treaties, travel, intercommunications, what happens in one space may well extend to others.

Figure 2: Local, National, Transnational, and Global Resonances with Political Communications including Physical Effigies

Effigies stand in as “proxies for real bodies” and may appear in “Internet memes, political cartoons, mainstream media, social media posts and material culture” (Schrift, 2016, p. 290). The materiality of protest effigies differ. From mass media coverage, they have been made of papier-mâché, rubber, plastic, paper-and-sticks, cloth, straw, wood, and other combinations of common materials. These depictions may be in three-dimensions or two-dimensions. Some may be human depictions painted in murals on walls. Others may be parts of art installations. Others may be integrated with street performances. Some are strung up with strings and can be made to move, such as nodding a head or waving or making certain bodily motions. Physical effigies appear in various incarnations, as persons, as animals, as inanimate objects, and others. (An example of an inanimate physical protest effigy has been a Trojan Horse, used to indicate a sense of threat to the population, through deception and hiding and malicious gifting.) The power of effigies, in part, is in their ability to reference some phenomenon in the real.

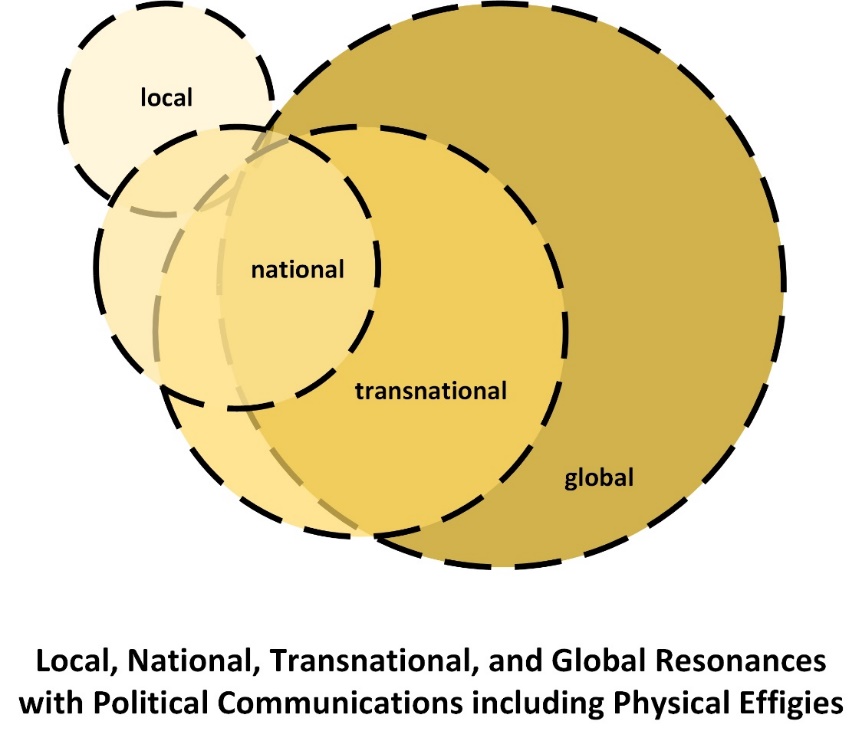

In digital space, effigies have been created from various digitalia: realia like photos, virtual reality avatars, social media accounts (of late historical figures), and others. In a user-generated social video series about international relations and politics, GZero World has a “Puppet Regime” humor segment that uses puppets of world leaders (physical effigies) to share social-political insights via social video (transformed to digital effigies).

This process of socio-political influence can often start with broadcast (one-to-many) strategic messaging and received messaging with individual and group sense-making and sense of personal relevance. This work involves the study of “physical-transcoded-to-digital effigy” category (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Born-Physical, Born-Digital, Transcoded, and Physical-Digital Effigies

This work is an early one, with a limited set of just over 1,000 social images (from Google Images), coded manually by the researcher. This nascent work does offer a novel approach to a topic with implications for both (local) micro and cross-border mass movements.

Review of the Literature

A basic definition of an “effigy” is “a representation of a specific person in the form of sculpture or some other three-dimensional medium” (“Effigy,” Nov. 14, 2019). Common “synonyms” for “effigy” include “statue, statuette, carving, sculpture, graven image, model, dummy, figure, figurine, guy, likeness, representation, image, bust, head,” according to the Oxford English dictionary online. In their usage as part of social protest, effigies have been an inherent part of political expression for hundreds of years from the colonial days (Peterson, 2015, p. 509) and through the present. Across the pond, “the use of an effigy personifying injustice in social protests…can be traced back to agrarian protests during nineteenth century England and Wales at least, when it was customary to use a ritual framework, ‘the ritual of justice’, involving the substitution device of an effigy and the release mechanisms of laughter, insults, and even the destruction of the effigy (Seal, 1988, as cited in Liao, 2010, p. 39).

As to those of different roles who have been documented as having been represented in effigy, they include committee chairs, corporate executives, a university president (Slonecker, 2006), on the lower profile ends of the spectrum, to national-level leaders (prime ministers, presidents, and others), global leaders, and others on the higher-profile ends. It does seem like represented personages have to attain a certain threshold of renown, to be targeted. In some historical demonstrations, effigies represented particular social groups or classes, like “bankers” (Liao, 2010, p. 40). Some effigial representations are of brand characters (McLeod, 1995), who are seen to represent the corporation. In other words, some effigies may be imagined characters. One visual showed a cartoon character, Bart Simpson, as a hanging and burning effigy.

For the Anonymous movement, the Guy Fawkes mask (effigy) is used not only to shield member faces but to suggest a brand identity of the “hero-avenger V” from V for Vendetta (both the book and the movie) (Ravetto-Biagioli, 2013, p. 186). In some cases, persons represented in effigy are a main focus of the particular demonstrations; in others, they are backgrounded and not even named directly. Persons may be depicted but in de-individualized ways “seen as opposing particularity” (Roosvall, 2014, p. 61).

In many senses, those who wield large amounts of power may garner the attention of detractors, so the reality of being depicted in effigy should not be derogatory in and of itself. A majority of political effigies seem to represent “the chief public enemy defined by the protesters” (Liao, 2010, p. 39), but this is not always the case. Some demonstrations have several effigies of focus. Some effigies are used in demonstrators in support of what the effigy represents (or is depicted as representing). One example in the image set was of a representation of the Pontiff, an exemplar around whom demonstrators rallied in support. There were photos built around an effigy of St. Mary, also an object of veneration at that demonstration. Another demonstration depicted a person seen to have been abused by the security services (Radwan, 2014, p. 62) as a hero. Prior rulers whose legacies are negative are ridiculed (Radwan, 2014, p. 63). In another, supporters of a political leader included effigial representations of a “rape accuser” who was seen to stand against a political leader (Robins, 2014, p. 109). Such depictions are very much context sensitive and seen through the subjective prisms of the demonstrators. Others depicted have been people seen as martyrs to a cause (Radwan, 2014, p. 63). A visual resemblance of an individual, as in a photorealistic likeness, is related to personal identity (Pentzold, Sommer, Meier, & Fraas, 2016), and this extends to lower-fidelity depictions. Some of the “dummies” are portrayed with “grotesque aesthetics” (Göttke, 2015, p. 129), in part to evoke “performed images of violent death” (Göttke, 2015, p. 129).

Practically, such demonstrations may enable people may make social change by garnering the attention of those in power. One author describes historical practices:

The distinction between embedded and detached collective identities corresponds approximately to the difference between local contention and national social movement politics in early nineteenth-century Europe, when a major shift toward the national arena was transforming popular politics (Tarrow 1994; Traugott 1995). In such forms of chain-making interaction as shaming ceremonies (e.g., donkeying, Rough Music), grain seizures, and burning of effigies, people generally deployed collective identities corresponding closely to those that prevailed in routine social life: householder, carpenter, neighbor, and so on. We can designate these forms of interaction as parochial and particularistic, since they ordinarily occurred within localized webs of social relations, incorporating practices and understandings peculiar to those localized webs. They also took a patronized form, relying on appeals to privileged intermediaries for intercession with more distant authorities. (Tilly, 1999, pp. 265 – 266)

How the demonstrators treat the effigy is part of the messaging. Some effigies are used to highlight social tensions and bring them to the awareness of the broader public. Others are to emphasize the disaffection in stronger terms. As part of dissent, demonstrators engage in “burning in effigy” and “hanging” in effigy based on “conventions of various traditional rituals and social practices (Göttke, 2015, p. 129). Toppling an effigy is another common practice, often applied to representations of “strongmen” leaders (Kraidy, Winter/Spring 2017, p. 1). Recently, an effigy of a U.S. president was stabbed during a demonstration. An effigy is not just used in representation but in a sense of destruction of the target individual and what he or she represents (in the same way as a “voodoo doll” defined as “an effigy into which pins are inserted” (Armitage, 2015), with the intention of causing “physical harm” on witches and breaking related spells (Hutton, 1999, as cited in “Voodoo doll,” Jan. 6, 2020). Sometimes, effigies are used in hate crimes (such as hanging effigies and nooses), with an inherent sense of threat (Rouse, 2012). In some cases, the destruction of the effigy is part of a ritual of “purification that mark the end of the old year and the beginning of the new and which exist all over Europe, in countries with a Hindu culture, and in many former European colonies” and which apply to the replacement of one political regime to another (Göttke, 2015, p. 132). Effigies used in protest may be engaged in “playful, symbolic strategies” alongside “more serious, discursive ones, and, of course, more violent ones” (Göttke, 2015, p. 142). The moods around effigy use may vary.

To understand the power of the proxy representation of the person, it helps to understand the human veneration of the dead. The dead are remembered with “a skeleton effigy or calaca” in celebratory remembrances of the dead (Ulmer & Freeman, 2018, p. 98). Dead bodies themselves have symbolic potency “due to their sacred and cosmic associations” (Anderson, 2006, as cited in Schrift, 2016, p. 281). In death, the bodies of “political leaders” are seen to reflect “national identity, social symmetry and culturally embedded understandings of death, funerary ritual and the afterlife” (Schrift, 2016, p. 281); many lie in state for the paying of respect and are worshiped and commemorated. Others who are less popular have their gravesites desecrated and their memory impugned publicly and privately.

Political posters with images of respective politicians may be treated as effigies, with those who engage in “counterpropaganda interventions” in an “I deface you” movement marking on the respective posters and easels in lead-ups to elections (Corrêa & Salgado, 2016, p. 129). In Brazil in 2010, this “Sujo sua cara” movement was started as “a response to the annoyance caused by the material illegally displayed on the streets” (Corrêa & Salgado, 2016, p. 129), with participants posting images of defaced posters posted on a social image sharing site, with paint covering up identities, verbiage written over the posters, gender switching, the drawing of a dollar sign on a forehead and devil horns on the head, and others. On the original posters are layers of additional meanings as a counterpoint. The co-researchers point to the role of social media in amplifying the message(s):

It is important to note that the defacement of electoral material occurred on the streets, but the ‘I deface you’ phenomenon was strengthened and gained meaning as a form of protest by organizing and sharing the images and the repercussion on social media. A single defaced easel on the street holds less meaning than when it is photographed and included alongside several others on social media accounts that give names and meaning to this phenomenon that, at first glance, appears to be a simple joke. (Corrêa & Salgado, 2016, p 142)

Such actions may suggest “disbelief in representative democracy” through “contemporary discursive practices” (Corrêa & Salgado, 2016, p 143). The initial messaging of political engagement may be usurped and appropriated into one of dissent, ad infinitum.

An earlier work described the defacing of political campaign posters in Kabul, Afghanistan, in the 2009 presidential elections. This event involved facial “mutilation” and was seen as “the handiwork of Islamist-tribal symbolic code, Islamic iconoclasm, and sympathetic magic” resulting in the shaming and dishonoring of the candidates “through the violence of defacement” (Whalen, 2012, p. 541). In this context, the human face “has been synonymous with honor and purity” (Whalen, 2012, p. 544), and their harm (such as through acid attacks and nose-cutting) redounds back to the individual in many cultures (Whalen, 2012, p. 545). The images from this context show posters of facial slashings, people with eyes gouged, bloodied heads, and removed facial parts like noses. The visual depictions convey the senses of frustration and hostility. Such depictions may, in some minds, be thought to affect the real world beyond the messaging of discontent.

Transcultural psychological phenomena (termed “sympathetic magic”) “impels the projection of power onto inanimate objects such as photographs, campaign posters, statues, effigies and images of sacred, powerful or venerated people whose deeds have been perceived as profane” (Perlmutter, 2011, as cited in Whalen, 2012, p. 544). One researcher describes the “Law of Similarity” trope applied to effigies, in which “an effigy or likeness of a person is used to mediate actions and effects that the magician and practitioner wish to visit on the real person in the social and material world” such as through voodoo dolls from Haitian traditions (Roberts, 2014, p. 13).

The personhood of the protest effigy represents certain policies and historical periods, among other things. They may also evoke something of so-called “identity politics” which pit certain people groups against others and minority groups against majority ones. One definition is that identity politics involves “struggles for justice and the right to maintain or cultivate group uniqueness by minoritarian groups in majoritarian contexts” and is “associated with postcolonial, post-Cold War and post-9/11 times” (Roosvall, 2014, p. 55). How groups around an effigy treat that effigy speak to their enacted sense of collective identity: they are showing their values by how they treat the effigy (whether in terms of the effigy as “other” or as “self”).

Some effigies are held in reverence by worshipers and are borne on shoulders. Some include effigies of religious figures; some involve religious iconography, like crosses and holy garb and books.

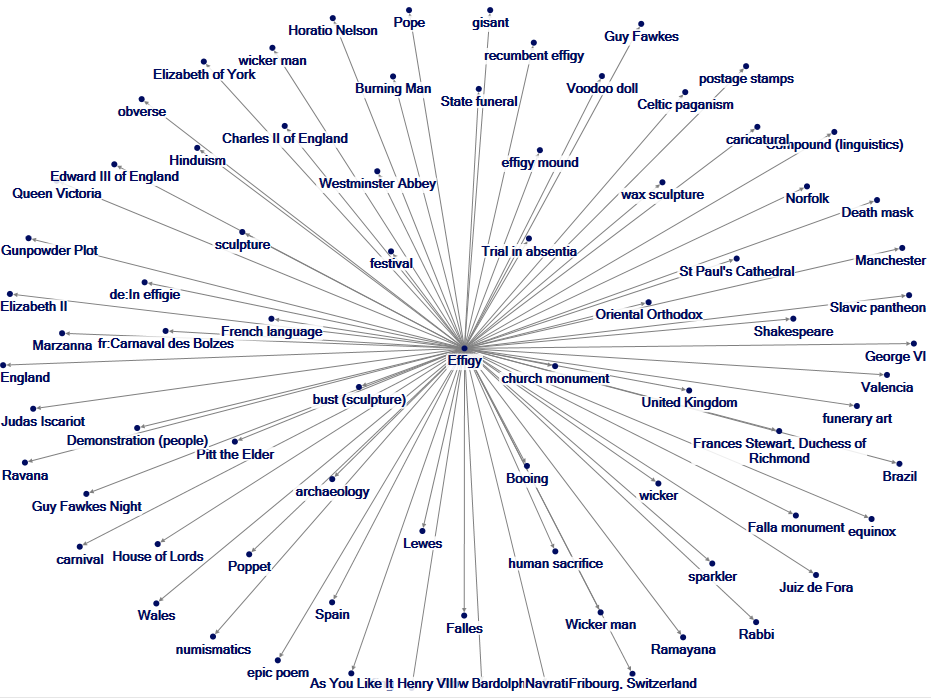

On social media, an “effigy” is related to both historical and present-day practice. In an article-article network of outlinks from the “effigy” article (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effigy) on the crowd-sourced encyclopedia site Wikipedia, there are ties to various materials and events and social practices. (Figure 4)

Figure 4: “Effigy” Article-Article Network on Wikipedia (1 deg.)

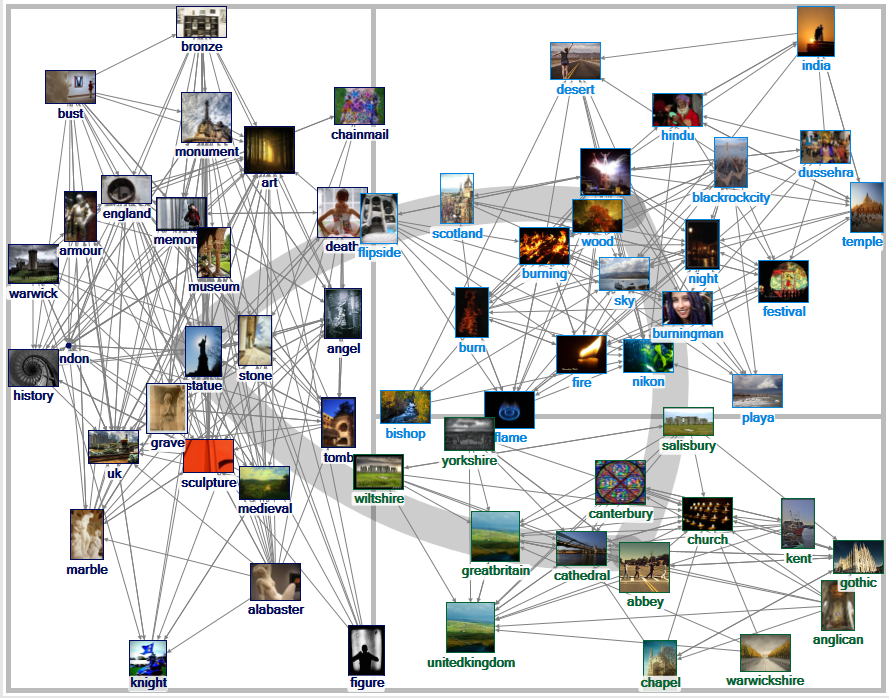

In a related tags network around the term “effigy” applied to social visuals on Flickr, three clusters of meaning may be identified:

Group 1: an anthropological, archaeological, and historical sense

Group 2: a modernist collective sense, such as around the Burning Man event

Group 3: practices within Great Britain (Figure 5)

Figure 5: “Effigy” Related Tags Network on Flickr (1.5 deg.)

Physical Protest Effigies in Global and Transnational Politics from a Social Imageset

To understand what may be seen in physical protest effigies on social media, a collection of social imagery was captured from Google Images, with the seeding term “effigy.” The auto-applied tags from the Google Image search include the following (in the order of their presentation): burning, burning man, the forest, american revolution, medieval, colonial, guy fawkes, lewes, tomb, clinton, bush, ravana, malifaux, hillary clinton, wooden, president, voodoo, bonfire night, knight, tax collector, philippines, stamp act, straw, royal, definition, paper, african, pope, donald trump, (and) stone. From the original image set, 454 were removed as being non-political ones, such as historical artifacts (stone statues, stone reliefs, carvings, and others), effigy mounds, and advertisements for products (pesticides, musical events, musical albums, a digital game). The remaining set contained 1,011 images. (Figure 6) Of these, 33 items were born-digital protest effigy representations and the rest physical ones rendered in digital format. [On Second Life™, a virtual immersive world, some of the effigies are labeled, such as “soul effigy” and “prayer effigy,” and one a jeweled one, and these seem to harken back to magical objects, not socio-political ones.] One was an animated gif showing digital fire consuming a particular effigy.

Figure 6: Some of the Imagery in the “Effigy” Visual Effigy Imageset from Google Images

In the imageset, there are items that range from pins and dolls to large posters hung from buildings and bridges. The messaging is overly-simplified, with upvotes or downvotes on particular issues. Politicians are over-simplified into caricatures and often depicted in demeaning ways. Some leaders are shown with people wearing jail garb dancing around them, standing in for the company the leaders apparently keep. Even with rough features defined, the faces are strangely recognizable, whether it is the wincing face of President Donald J. Trump with dramatic eyebrows and an expressive mouth…or Greta Thunberg with her signature braid…or a political figure as Judas Iscariot, embodiment of a traitor. Some effigies are human-sized stand-up cardboard figures, created from photos. Some public figures are not necessarily recognizable, if not for captions or signs… (A “Sarah Palin effigy burned on bonfire” is one example.)

Some effigies were pinatas, that were duly being smashed with a stick. Indeed, the images show effigies being beheaded, defaced, bashed, shot (a giant head with a bullet hole in its depicted forehead), and even praying for an assassin (based on holding a sign asking for that outcome). Some of the demonstrations involved prayer and the burning of incense. Some involved the burning of candles.

A set of questions were created to explore the imageset. These are set up in six general categories.

1. Real-Life Personages

- Which global leaders and other personages attract the most lightning rod sorts of attention? Why?

- What are the most common personal attacks in persons represented in protest effigies? How is their dignity attacked? Their personhood? How are political leaders punished for their stances and representation contrary to the desires of the dissenters?

- How are political effigies styled? What messages does the styling evoke?

2. About Demonstrators

- Who is being appealed to with the physical effigies and political messaging? What value is being offered in the particular collective groups, and why? Who is being left out in the messaging, and why? (If blame is being apportioned, who is being blamed?)

- How does the effigy help create the identity of the demonstrators, who stand against the effigy as other / or who stand with the effigy as the same?

3. Physical Materials for the Construct of Protest Effigies

- What are the most common analog materials used to create effigies?

- How are protest effigies presented in physical space?

- How are physical protest effigies presented in social digital spaces in two-dimensional imagery?

- How are effigies re-used transnationally (if any)?

- How do still social imagery of political effigies compare to social videos available (on YouTube)?

4. Actual and Symbolic Treatment on the Protest Effigies

- What are some common ways that protest effigies are attacked? Verbally? Physically? And others?

- What are some non-aggressive ways in which protest effigies are treated?

5. Political Dialogue and Protest Effigies

- How are protest effigies a part of political dialogue?

- Based on the proliferation of social imagery on formal mass media and on informal social media, what sorts of power do contemporaneous political effigies evoke? How?

- Do contemporaneous modern-day effigies have ties to prior ones, used culturally and ritually? What are some senses of the magical uses of effigies to call up magical powers?

6. Global and Transnational Issues

- According to reverse imagery searches online, in a global sense, what are the main issues being protested in political effigy through social imagery?

- What parts of the world are the locales of the most political effigy-based expression in social imagery? Why might these be so?

- How do various governments respond to political effigies, and why? (In some countries, public protests are precluded by law, and demonstrators put themselves at great risk of harm when they engage in such activities.)

Global leaders. The global leader who appeared in a majority of the images were U.S. President Donald J. Trump, mostly in opposition to him and his cabinet’s policies. Anti-Trump protests show him as militaristic and grubbing, holding weapons and bags of money, with four arms positioned as a swastika. (Online, this was referred to a “Trump-Hitler statue.” A number of British leaders also featured in the visuals: Theresa May, John Bercow, Jeremy Corbin, and Boris Johnson. Queen Elizabeth II appeared in a few. Several related images showed a bicycle racing phenom selling his racing bicycle (“Armstrong Guy”), given the sense of his “villainy” for drug-use. This is an expression against his lack of fair play. One leader was compared with “Judas” and labeled as such as a “betrayer.” Young environmental activist Greta Thunberg’s visage appeared in some of the photos of this “effigy” set, often as a photo or in person. A cube with the faces of Hitler and other leaders was burned amongst a large crowd, with the message on the top of the cube reading, “NEVER AGAIN.”

Global and transnational issues. A number of effigies related to “Brexit,” the vote by Britain to leave the European Union. One politician was depicted draped in the country’s flag with his buttocks showing. Another effigy showed a politician with the message of “FU to the EU.” Competing politicians were depicted in a visual holding the heads of the competing politicians. In another, a prime minister was depicted as having a Pinocchio nose (to indicate deception and lying) with “Brexit” written on it. The #metoo movement (an anti-sexual harassment movement primarily on behalf of women but extended also to general populations) was represented with an effigy of Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein holding an Oscar. One effigy showed anti-Semitism in the beating of an effigy representing Judas (as a Jewish individual) as part of an Easter celebration in Poland (“Polish church condemns beating of Jewish effigy in Poland,” Apr. 22, 2019).

About demonstrators. The respective demonstrators are seen to have stances on particular issues: anti-Trump, pro- or anti-Brexit, anti-doping in bicycle racing, and others.

Physical materials. The physical materials used in the images include the common materials like paper, wood, foil, and others. There was also the use of various balloon materials, plastics, rubber, and others.

In terms of depictions on social video, “effigy” brought up various music videos…some historical artifact ones…and then videos of protest effigies burning. These did not add much to the research in this framework.

Treatment of protest effigies. The various effigies were shown in photos being put together and raised up…but also being taken down, burned, stepped on, and otherwise attacked, abused, and destroyed.

Political dialogue and protest effigies. In the visuals, the protest effigies are a center of attention. Those who would address the crowd are sometimes standing next to the representational effigies about their cause. As for whether the demonstrators were trying to evoke magic, the visuals did not evoke that vibe.

Global and transnational issues. Given the decontextualization of the images, various efforts were made to understand the context of the usage of the respective protest effigies. The image name, reverse image searches, and Google searches were all used to better understand selected images. In the reverse image searches, invariably, the images linked back to both mass media coverage and social media postings. [The free web-facing TinEye was used, which compared the uploaded images against some 38.6 billion images. The URL for TinEye is https://www.tineye.com/.] Not all images are easily understandable from the visual alone. One image of children standing next to an effigy lying face down on a pavement was about the lack of vaccination of airline crews for a particular country and the sense of risk from that oversight. Even with TinEye searches, a number of visuals were not found in their databases and remained a mystery. Some of the images were found to be local events, without particular national, transnational, or global relevance.

This analysis suggested that many of the main issues of the time—U.S. President Donald J. Trump’s nationalism (and other policies), Brexit, and environmentalism—were central focuses of demonstrations with local, national, transnational, and global implications. (Some visuals could be found with a simple Google search by what was visually depicted, without the need for an actual reverse image search.)

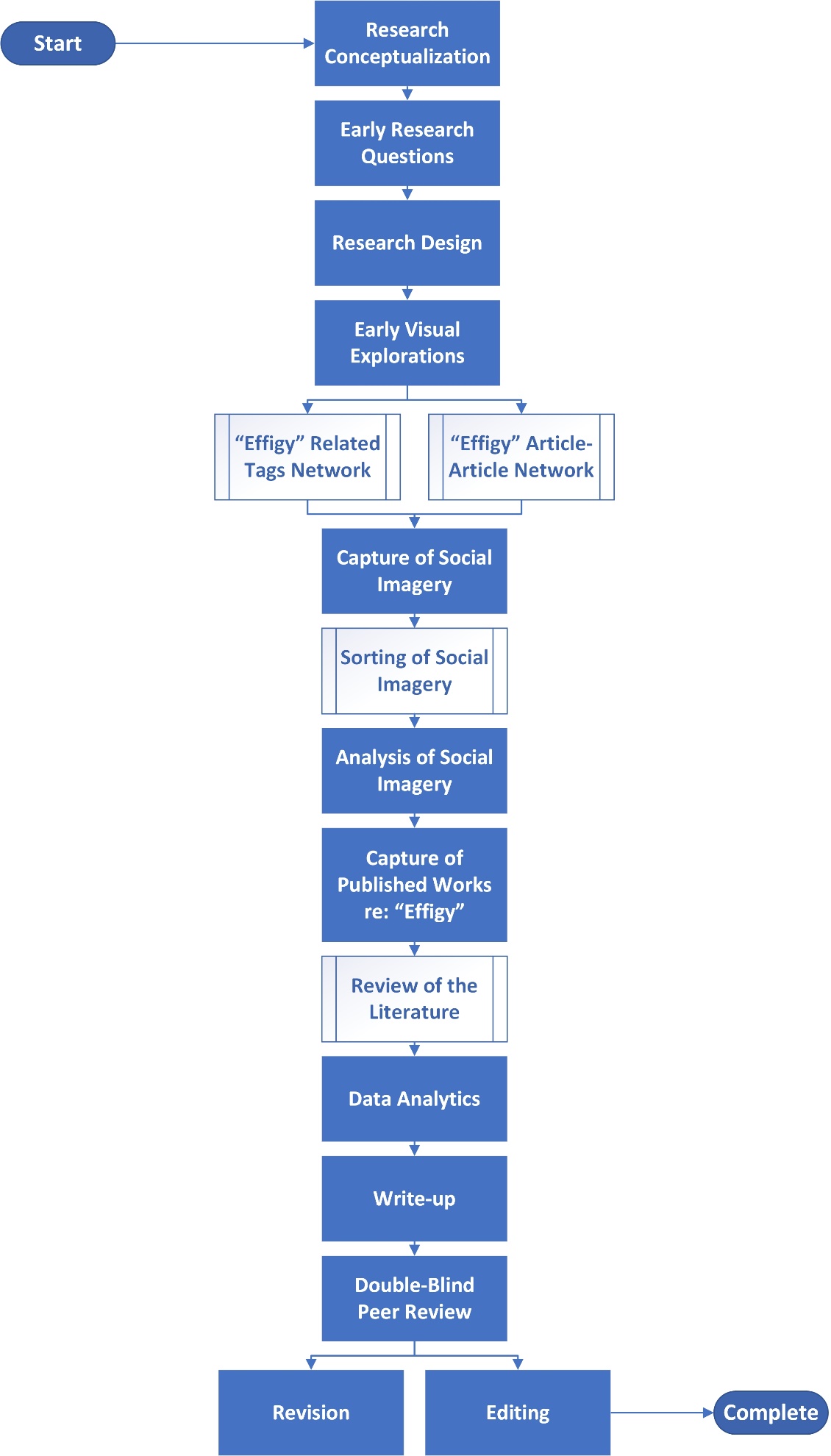

In many ways, the target research questions were only partially answered. This could be based in part on the fact that the imageset did not include all possible images. To summarize, this research was conducted as follows: research conceptualization, early research questions, research design, early visual explorations, capture of social imagery, analysis of social imagery, captured published works re: effigy, data analytics, write-up, double-blind peer review, revision and editing (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Workflow of the “Visual Protest Effigies in Global and Transnational Politics” Research Project

Various types of street art and performance art have been harnessed to capture widespread attention to particular issues and political stances. The “guerrilla design” and “guerrilla art” approaches have been used to protest particular organizing systems, like capitalism (Bigat, 2012, p. 1028). Effigies that are harnessed for such social spectacles and socio-political performances tend to look rough and uneven.

Discussion

Representing issues in human effigy has been parts of human practice for many years. In the modern era, it is not particularly fair for targeted individuals to have their reputations tarnished in effigy. After all, in any number of controversial issues, there will be a range of opinions in a population, including extreme ones. Effigies depict something of how a group depicts an individual as representation of policy or practice; they depict something of how people view themselves in relation to that individual and represented issue (at both group and individual levels). Expressing through effigies is about the other, the policies, and the self, in a particular time and place.

A deeper “root origin” or “root cause” for the protests and effigies may include any or some combination of the following:

- Perhaps there is a conflict of understandings of the world and lived narratives.

- Perhaps there is a struggle over rights.

- Perhaps there is a struggle over resources.

- Perhaps there are differences in desired futures and what different current policies or near-future policies may affect the future.

- Perhaps there are not clear understandings of complexities and tradeoffs around particular policy issues.

- Perhaps there are personal dislikes in how public figures are conveyed to the public.

- Perhaps there is a sense of personal offense to values and sense of self and senses of history in present-day actions.

In a lived sense, there are many reasons why people may choose to protest and to portray an issue in the form of another person or object or context. There is something “co-embodied” in person/persons-effigy/effigies relationships as expressed in protests, through shared spaces, through adversarial or aligned depicted relationships, in flames, in violence, in reverence. From a distance, it is possible to make erroneous inferences of public figures which go un-challenged; it is possible to cast aspersions on other people’s reputations even with insufficient evidence.

Finally, this work is descriptive, not prescriptive, in terms of visual effigies. Its focus has been on social imagery depicting various effigies used in public demonstrations for a variety of purposes.

Future Research Directions

Physical protest effigies, as dramatis personae in acted political dramas on the world stage, are never the only element in political messaging and activism. They are part of a larger campaign. They may appear in more than one march (like the infamous gas-filled “Trump baby” balloon). Effigies are used in various ways to express dissension against some policies and platforms and persons and support for others. While the messaging of the effigy is inherently vague [with “the suspension of fixed meaning” (Göttke, 2015, p. 142)], the message is often complemented and fine-tuned in manifestos, websites, social media messaging, flyers, and other communications. The semiotics of political expression include various signs and symbols: banners, icons, visuals, slogans, sound snippets, physical objects (with tactual features), and other elements. There may be a range of political action events: educational teach-ins, online signature collections, fund-raising events, voter drives, walking tours and street marches, speeches, performance art, mock trials, re-enactments, film showings, strikes, boycotts, hunger strikes, mass demonstrations to provoke police actions, and sometimes, actions that escalate to violence. Researchers may also want to explore how effigies are used to construct public awareness and discourse, engage in political change-making, and advance particular agendas and stump others. The methods of orchestration would be of public interest.

In some ways, expression through protest effigies is about a lack of direct power, requiring a need to go to indirect power (through proxy actions). And yet, there is something about the power of free speech (often tied to democratic citizen power) to express ideas that may be disagreeable to those in power. Such communicative actions seem to be both potentially cathartic (releasing tensions and dissipating potential for future actions) and reinforcing (rallying power and energy for future actions). From the psychological angle, there may be something of spite and schadenfreude in the mistreatment of human-based effigies, suggesting that people may derive pleasure from another’s misfortune, even if it is in figurative representation. Here, too, a person is treated as shorthand for social disagreement, and the individual is treated as a single-dimension personality, without the capability of reconsideration of stances. Their depiction offers a way of “calling out” living public individuals and their supporters (and evoking legacies of those who have passed on).

How effective are these protest and advocacy effigies in attracting allies, maintaining supporter loyalty, affecting larger discourses, and ultimately affecting social change? Effigy-based performances are “ineffective in delivering a straightforward message, and on its own, inept at effecting lasting political change” (Göttke, 2015, p. 143), so what do these actually accomplish for the polity and the political system? What are physical political effigy features that make for effective persuasion (in the particular social context and time)? Are there some universal observations that may be made about effigies used in social-political protests? Which are the voices that are amplified through effigy-based performances, and why? Are such protests about the release of social tensions at the concentration of power held by a few (based on how humans socially organize), or is it about the need for entertainment and meaning, or what combination of human interests and needs? (The global nature of the uses of effigies in public demonstrations suggests something of social learning—people learning from others by observation and emulation—and maybe something of inherency in people.)

Figure 3 pointed to born-physical, physical-transcoded-to-digital, born-digital, and digital-transcoded-to-physical effigy categories. There is room to study various types of effigies in various forms beyond what was studied in this work (physical-transcoded-to-digital effigies). In this work, this researcher came across born-digital effigies for various political expression (given the ease of “Photoshopping” images from online sources). [One study examined some manipulated images of Donald Trump from social media to understand born-digital effigies based on original photos but usurped for political statements and resistance. Some of the names that the author has applied to the images provide a sense of the “manipulations,” a term applied by the author (Kharel, n.d., p. 1): “Small Trump with Melania,” “Obama Carrying Trump,” “Putin with Tiny Trump,” “Tiny Trump Signing Executive Orders,” “Trump as a Bride in a Fake Time Cover and the Original Magazine Cover,” “Theresa May Holding Hands with Trump,” “Face Swap of Trump and Theresa May,” “Trump as Elizabeth II,” “Trump with Kate Middleton,” “Queen and Kate Middleton (Original),” “Outline of Trump’s Iconic Hairstyle,” “Bald Trump,” “Trumps Hair Wave and a Surfer,” “Trump’s Hair and Corn Silk,” “Trump’s Hair and Horse Tail,” “Trump and Putin Camping,” “Trump and Putin in Leather Jacket,” “Putin and Trump in (sic) the Same Horse,” “Putin and Trump Go Hunting,” “Baby Trump Sculpture to Protest Greenpeace in Hamburg,” “Baby Trump Vinyl Sculpture,”…”Trump’s Tshirt and Mis-Quotes Button,” “Trump’s Pen, and others (Kharel, n.d., pp. 4-5). Many such “meta-manipulations” are about diminishing the person and what he is seen to represent. The author describes “meta-manipulations” as a “reference to what satirists call meta-humor, meta-joke, or meta-caricature” with a focus on the “manipulation of the already manipulated images” (Kharel, n.d., pp. 83 – 84) and the assumption of endlessly recursive manipulations possible.] [As a side note, with the divisiveness of people either pro-Trump or anti-Trump, many of the kitschy toys and shirts may be created not by any true believers one way or another but entrepreneurial individuals who see an opportunity to earn some money in a DIY age.] Then, too, there are a number of non-human political effigies that stand in for various practices and ideas. These would be of interest for further study.

Certainly, various case-based approaches may be taken to analyze the roles of effigies used in political expression. Who are the demonstrators? What political (and personal) messages are being communicated in the demonstrations? How is the effigy used? How is it depicted? What parts of the individual persona is picked up on in the simplified public messaging? How efficacious was the demonstration? These and other questions may be addressed, for example.

Language is seen as a “basic component of a political effigy” as the instantiation of the political self of the living politician (Zimny & Żukiewicz, 2010, pp. 311 – 312). The role of language in the creation of protest effigies would be promising as well.

On social media, there are various types of messaging in relation to protest effigies. People may be seen with selfies of themselves as they make faces and gestures, next to a protest effigy or in front of one. Some are taken in physical locations. Some are mock-ups using photo editing in layers. Others are created with chromakeying (green screens). Online is very much a local-to-global public square, and pursuing such research may also be engaging. The effigies serve expressive needs and instrumental ones. For the first, they are messages of protest and political change and moral high ground; for the latter, they are objects around which people may gather for collective interests and change promotion.

Conclusion

If the Internet, WWW, and social media have enabled the broad global public to be “woke” to social justice issues, understanding how these various issues are brought to light through various social intercommunications may enhance the work. In this space, physical effigies captured in social imagery may indicate something of the physical-cyber confluence and the extension of voices between the analog and the digital.

Whereas common citizens have a legal right to their own likenesses (in every way that they manifest—physical, visual, voice, and other) and privacy, public figures often have fewer privacy protections because their lives are seen as “newsworthy” and somewhat belonging to the public. There is a public interest over the lives and thinking and health and actions of various public figures, in a sense. This distinction means that mass media can cover newsworthy public figures in ways that are not seen as trespassing of a private individual. This also means that their likenesses may end up with starring roles in social demonstrations, or their likenesses may make cameos in social imagery. Mass folk narratives of the powerful involve stories of self-dealing, corruption, venality, and error, and in many cases, these are not wholly baseless. Public figures have to make peace with the need to have a thick skin; they must be able to dissociate from others’ external representations of themselves, even in the absence of any firsthand knowledge. They have to see effigies as characters’ (villains and heroes) in others’ plays of political theater and social commentary. These are pseudo-surrogates or substitutes for an embodiment of policy; they represent the passive recipients of crowd anger or frustration or lack of understanding or other factors. [Indeed, a light monitoring of general engagement with politicians can show a willingness to take quotes out of context, to misrepresent meanings, to misattribute, to cast aspersions on others, and to engage in character assassination. From the outside and from a distance, it can be hard to understand another person, much less mind-read. And yet, that is not uncommon practice for many. The “fundamental attribution error” involves people’s tendency “to under-emphasize situational explanations for an individual’s observed behavior while over-emphasizing dispositional and personality-based explanations for their behavior” (“Fundamental attribution error,” Mar. 14, 2020). This human tendency, at population scale, can result in major distortions of leader intentions and personalities. Sometimes, these are expressed in effigies, which are then destroyed as part of the theatrical public discourse.]

In some (more extreme) cases, the crowds erroneously ascribe intentionality; they engage in straw man debates (debunking a supposed—but fallacious—argument or stance or action by the target individual). The reputations of public individuals have an impact on their public lives and their formal and informal roles, particularly in democracies. The concept of “mob rule” alludes to the fast, first-impressions, and almost unthinking approaches of some crowds set afire by rumors and impressions and self-righteousness. The public has important roles in self-governance in democracies, and by design, there are many channels through which they can communicate their senses of the world, including the physical public square and the physical streets, for demonstrating and marching publicly. These offer ways to communicate ideas to political leaders, and they serve as a social tension relief valve (a cathartic socio-psychological function), in some cases, and inducements to further actions in others (a reinforcement socio-psychological function).

In this work, the author engaged the so-called “general readability of images” (Göttke, 2015, p. 131). The visual analysis of physical protest effigies represented in digital social imagery (photos in this case) shared on social imagery platforms show something of political massmind in terms of issues of concern. These visuals shed light on local issues with some traction at the national, transnational, and global levels. These also show that protest effigies have a place in the human iconography of protest.

In the era of Deepfakes (from “deep learning” and “fake”), the ability to create videos of individuals talking to the camera based on the use of artificial intelligence on existing video and audio files, how will digital protest effigies manifest? Will the politics of personal destruction continue, motivated by dissatisfaction and anger?

References

Armitage, Natalie (2015). “European and African Figural Ritual Magic: The Beginnings of the Voodoo Doll Myth”. In Ceri Houlbrook and Natalie Armitage (eds.). The Materiality of Magic: An Artifactual Investigation into Ritual Practices and Popular Beliefs. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 85–101.

Bigat, E.C. (2012). Guerrilla advertisement and marketing. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 51, 1022 – 1029.

Corrêa, L. G., & Salgado, T. B. P. (2016). “You deface my city, I deface you”: the practice of defacing political posters. Comunicacao, Midia E Consumo, 13(36), 127 – 145.

“effigy.” (2019). Oxford English Dictionary.

“effigy.” (2019, Nov. 14). Wikipedia. Retrieved Nov. 15, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effigy.

“Effigy mound.” (2019, July 30). Wikipedia. Retrieved Nov. 15, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Effigy_mound.

“Fundamental attribution error.” (2020, Mar. 16). Wikipedia. Retrieved Mar. 16, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamental_attribution_error.

Göttke, F. (2015). Burning effigies with Bakhtinian laughter. The European Journal of Humour Research, 3(2/3), 129-144.

Kharel, S. (n.d.) The politics of manipulated images in Social media. 1 – 100.

Kraidy, M. M. (2017, Winter/Spring) Creative Insurgency and the Celebrity President: Politics and Popular Culture from the Arab Spring to the White House. Arab Media & Society, 23, 1 – 4.

Liao, T.F. (2010). Visual symbolism, collective memory, and social protest: A study of the 2009 London G20 protest. Social Alternatives, 29(3), 37 – 43.

McLeod, D. M. (1995). Communicating deviance: The effects of television news coverage of social protest. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 39(1), 4-19.

Panetta, G. (2015). Stewardship and global social media. Character and…Discomfort, 1(2015), 10-25. Retrieved Nov. 14, 2019, from http://digitalud.dbq.edu/ojs/character.

Pentzold, C., Sommer, V., Meier, S., & Fraas, C. (2016). Reconstructing media frames in multimodal discourse: The John/Ivan Demjanjuk trial. Discourse, Context and Media, 12, 32 – 39.

Peterson, A. (2015). Social protest. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2(22), 506 – 511.

Polish church condemns beating of Jewish effigy in Poland. (2019, Apr. 22). Ynet News. Retrieved Feb. 11, 2020, from https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-5498246,00.html.

Radwan, N. (2014). Revolution to revolution: Tracing Egyptian public art from Saad Zaghloul to January 25. Cairo Review, 14, 59 – 63.

Ravetto-Biagioli, K. (2013). Anonymous: social as political. Leonardo Electronic Almanac, 19(4), 178-195.

Roberts, L. (2014). Marketing musicscapes, or the political economy of contagious magic. Tourist Studies, 14(1), 10-29.

Robins, S. (2014). Slow activism in fast times: Reflections on the politics of media spectacles after apartheid. Journal of Southern African Studies, 40(1). 91 – 110.

Roosvall, A. (2014). The identity politics of world news: Oneness, particularity, identity and status in online slideshows. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 17(1), 55 – 74.

Rouse, M. (2012). Combating hate without hate crimes: The hanging effigies of the 2008 presidential campaign. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, 25, 225 – 247.

Schrift, M. (2016). Osama’s body: death of a political criminal and (Re) birth of a nation. Mortality, 21(3), 279-294.

Slonecker, B. (2006). The politics of space: Student communes, political counterculture, and the Columbia University protest of 1968 (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

Straus, E. W. (1965). Born to see, bound to behold: reflections on the function of upright posture in the esthetic attitude. Tijdschrift voor Filosofie, 27(4), 659-688.

Tilly, C. (1999). From interactions to outcomes in social movements. Conclusion. In M. Giugni, D. McAdam, and C. Tilly’s How Social Movements Matter. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 253 – 270.

Ulmer, G. L., & Freeman, J. C. (2018). Beyond the virtual public square: ubiquitous computing and the new politics of well-being. In Augmented reality art (pp. 95-113). Springer, Cham.

Voodoo doll. (2020, Jan. 6). Wikipedia. Retrieved Jan. 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voodoo_doll#cite_note-FOOTNOTEArmitage201585-1.

Whalen, K. (2012). Defacing Kabul: an iconography of political campaign posters. cultural geographies, 20(4), 541-549.

Zimny, R., & Żukiewicz, P. (2010). The emotionality of Jarosław Kaczyński’s Language versus the efficiency of the political messaging: a political-linguistic survey.

Key Terms

Deepfakes: The use of another person’s visual and auditory likeness in a video by using various artificial intelligence (like artificial neural networks)

Dramatis Personae: A character in a drama

Effigy: A physical representation of a person

Global Political Protests: Political expression for change around the world

Social Imagery: User-generated images shared on a social image sharing site

Transnational Political Protests: Political expression for change across national boundaries, internationally

Visual Protest Effigy: A visual depiction of a person or entity or object as part of political expression (as in the context of a demonstrations)