2 Chapter 2: Practical Wisdom

“Excellence is never an accident. It is always the result of high intention, sincere effort, and intelligent execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives – choice, not chance, determines your destiny.” – Aristotle

Guiding Questions for Chapter 2

- What is practical wisdom?

- How does practical wisdom connect to teaching?

- How does understanding practical wisdom help me become a better teacher?

- What is the Golden Mean and how does it connect to teaching?

Overview

Teaching and learning are complex activities. It follows that learning to become a teacher is also complex. In this book, we attempt to clarify what it means to be an effective teacher, one who motivates and maximizes learning. Our search is not bounded. We will look for good ideas wherever we can find them. They may be old or new, based on research or practical experience, or they may come from teachers or students.

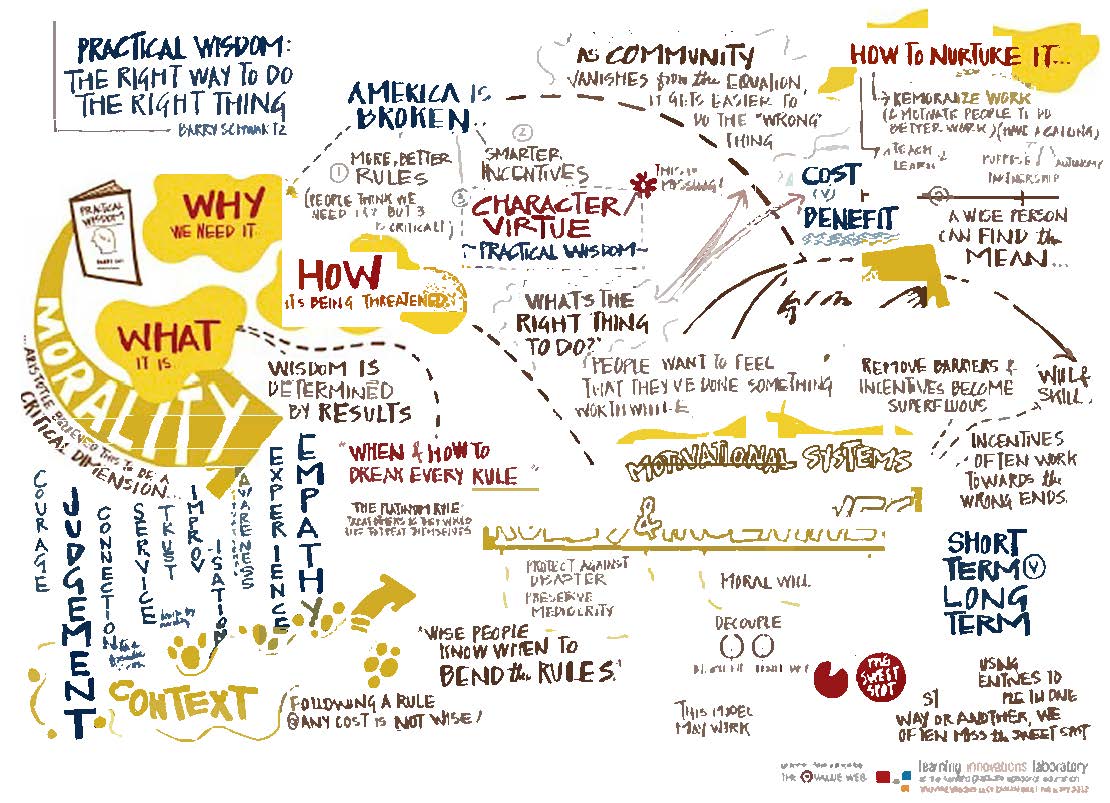

We begin by examining an ancient idea, practical wisdom, and its relationship to effective teaching. In our view, there is no better place to begin. Practical wisdom is knowing what is good, right, or best, given a particular set of circumstances. The roots of this idea can be traced back more than 2,400 years to to Aristotle in Ancient Greece. Aristotle attempted to distinguish different kinds of knowledge—different ways of knowing. Practical wisdom (what Aristotle called phronesis) was distinct from other kinds of knowledge such as science (what Aristotle called epistime) or art (what Aristotle called techne).

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle writes (1140a24-1140b12):

We may grasp the nature of prudence [phronesis] if we consider what sort of people we call prudent. Well, it is thought to be the mark of a prudent man to be able to deliberate rightly about what is good and advantageous…But nobody deliberates about things that are invariable…So…prudence cannot be science or art; not science [episteme] because what can be done is a variable (it may be done in different ways, or not done at all), and not an art [techne] because action and production are generically different. For production aims at an end other than itself; but this is impossible in the case of action, because the end is merely doing well. What remains, then, is that it is a true state, reasoned, and capable of action with regard to things that are good or bad for man. We consider that this quality belongs to those who understand the management of households or states.

The knowledge of science was a knowledge of universals (e.g., A2 + B2 = C2), things that were universally true and not bound by place or time. The knowledge of art (i.e., skill) was a kind of knowledge that could be applied to a task and set aside (e.g., the knowledge a shoemaker possesses). Practical wisdom, however, was a bit more complicated, interesting, and for teachers, important. Practical wisdom is concerned with both the context and reasons for the decisions we make. It is not the kind of knowledge we selectively apply; it is a knowledge we carry with us at all times. It is based on our past experiences, our values, our moral sensibilities, and our knowledge of ideas that might be brought to bear on a particular problem. In short, practical wisdom is doing the right things, for good reasons, in the best ways.

Every day, teachers face scores of decisions that influence student learning and development. Even seemingly simple decisions may be more complex than they appear. Should you allow a student to turn in her paper late? How should you respond to Josh and Steve who are talking, again, during 5th period? What should you teach next week, and how should it be organized? How should you evaluate your unit on mammals? The best teachers are equipped with a well-developed and thoughtful intellectual framework that helps them to make sound educational decisions based upon a myriad of factors that influence those decisions.

This book will enable you to construct your own initial framework, of ideas, skills, and dispositions, that will help you make educational/teaching decisions and empower you to act on those decisions. In essence, one of the primary goals of the book is to inform and hone your ability to reason practically in and out of the classroom.

Of course, we are not the only people who recognize the importance of practical wisdom. Watch the following video and ask yourself how these ideas connect to teaching.

Read: Shulman, Lee S. “Practical Wisdom in the Service of Professional Practice.” Educational Researcher : A Publication of the American Educational Research Association. 36, no. 9 (2007): 560-563.

Read: Bassett, Caroline L. “Understanding and Teaching Practical Wisdom.” New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, no. 131 (Fall 2011): 35–44.

Questions

- How, specifically, is practical wisdom related to becoming a great teacher?

- How can teachers further develop or hone their practical reasoning abilities?

- To what extent does practical wisdom connect to the subjects you teach?

Searching for the Golden Mean

Great teachers are able to find the balance among competing virtues in teaching. Aristotle theorized that almost any virtue can become a vice; you can have too much or too little of a virtue or fail to balance a virtue with other virtues. So, for example, teachers need some level of confidence to be able to effectively lead their students but not so much confidence that they become arrogant. Confidence should also be balanced with humility, adaptability, reflection, etc. Aristotle referred to this balance as the Golden Mean. What virtues are most important to you and what are their corrupt forms?

Read: Hostetler, Karl D. “Beyond Reflection: Perception, Virtue, and Teacher Knowledge.” Educational Philosophy & Theory 48, no. 2 (February 2016): 179–90.