6 Chapter 6: Curriculum Planning

Guiding Questions for Chapter 6:

- What resources are available to teachers to plan the curriculum?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of Understanding by Design as a model for curriculum planning?

- What is Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy and how does it help teachers construct questions and objectives?

- How do effective teachers plan clear, coherent, and standards-based lessons?

- How do effective teachers plan clear, coherent, and standards-based mini-units?

Introduction to Planning

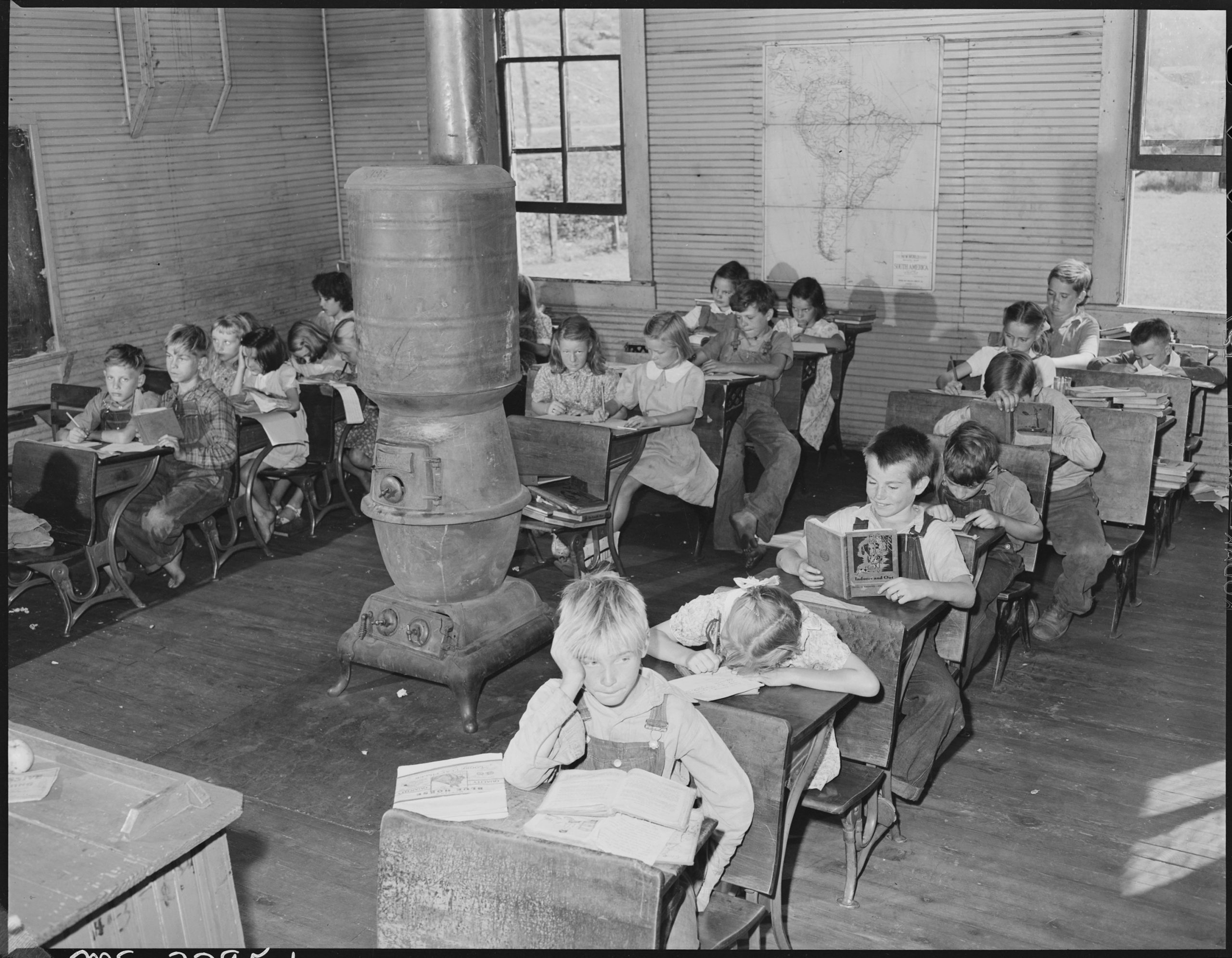

Even teachers who taught in the one-room schoolhouses had to answer basic questions about the curriculum.

Today, teachers are not alone in creating their curriculum. A variety of resources exist—state and national standards, textbooks, district-level curriculum guides, statements from professional organizations, and even other teachers within your building. One of the great joys of teaching is planning a lesson, unit, or course and having it succeed—knowing students have learned the right stuff, in best ways, for good reasons.

Planning clear, age-appropriate, engaging instruction is essential to becoming an effective teacher. All teachers must answer WHAT, HOW, and WHY questions about the curriculum. What is most important to teach? Why? How will content be organized and structured? Why? What strategies are best suited to teach a certain idea or skill? Why? How will I assess student progress and mastery? Why?

This chapter is designed to help inform your curricular judgments.

Overview of Planning

Instructional planning occupies a central part of the life of every teacher. Every teacher, of any subject, at any level must make decisions about the curriculum. And, every teacher plans the curriculum in a unique way. The lesson or unit plans of veteran teachers are often focused on a few core elements whereas the plans of a novice tend to include a little more detail. Your professors also require that you plan in more detail than you will when you have your own classroom; your lesson and unit plans allow us to “see” and “hear” your emerging ideas as a teacher. Without sufficient detail, we cannot provide adequate feedback, coaching, and guidance. This is the one time in your career when you are able to benefit from the scrutiny, wisdom, and experience of mentors who all want the same goal: for you to become a great teacher! So, take instructional planning seriously as it requires you to synthesize and apply important ideas in curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

Models of Curriculum Planning

If you took a survey of 100 teachers and asked how they planned the curriculum, you are likely to get 100 unique responses. In time, you will formulate your own model, applying principles and ideas that make the most sense to you and your circumstances, based on your experience and wisdom of practice.

Teachers must consider planning at a variety of different levels. The most general level of planning is at the course level—what do I want students to gain from this course? What knowledge, skills, and dispositions are of most worth?

Course planning is important—it helps teachers carefully consider their long-range goals. Within courses, teachers must consider how their courses will be organized into smaller units. Instructional units are typically two to three weeks of instruction focused on a single theme or question. Teachers must also consider specific lessons that will comprise each unit.

For effective teachers, instruction is purposeful and intentional; never aimless or accidental. Effective teachers carefully consider what content and skills they will teach, how the material will be organized, how students will learn, and what will constitute evidence of student learning.

One of the most prominent models of curriculum planning is known as Understanding by Design, developed Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins. The model requires teachers to ask and answer a number of practical questions:

- What is most important for students to learn?

- What are my short- and long-term goals?

- What essential questions will we be asking and answering?

- How will I know if students have learned?

- How is the content best organized?

- How will students learn this content best?

Read Understanding by Design White Paper from Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development and watch a two-part video from Grant Wiggins explaining his model of planning.

For a practical example read: Sumrall, William, and Kristen Sumrall. 2018. “Understanding by Design.” Science & Children 56 (1): 48–54.

Essential Questions

One of the most challenging parts of the Understanding by Design model is formulating essential questions. Essential questions help students and teachers focus on the most important information in the most interesting ways. Some of the basic elements of writing effective essential questions include:

- Aiming at the philosophical or conceptual foundations of a discipline

- Having ideas or issues recurring naturally throughout one’s learning

- Raising other important questions, often across subject-area boundaries

- Having no one obvious right answer

- Being framed to provoke and sustain student interest

Watch the following video to gain additional insights into framing essential questions.

Practical Principles

In addition to operating within some model, teachers also plan the curriculum with certain principles in mind. Years ago, I (Tom Vontz) sat down and constructed a “top ten (twelve) list” of planning principles—big ideas that guided planning decisions:

- Plan with students in mind.

- Instructional planning is an inexact science.

- Teachers enjoy various degrees of autonomy in planning and implementing the curriculum.

- The beginning and ending of courses, units, and lessons are very important to the learning process.

- Assemble resources before you attempt to start planning.

- Remember the big picture/long-range goals.

- Vary instructional strategies.

- Plans should be considered tentative.

- As a guide to instruction and learning, strive for CLARITY in planning.

- Plan with assessment and evaluation in mind.

- Keep plans simple.

- Save your plans and stay organized.

Questions

What principles do you think are the most or least important on the list?

What additional principles would you include on your own list?

Maximizing Resources

Students sometimes ask us, “What is the best lesson you ever taught?” We tend to think of lessons that made some real difference in the life of a student. Many of the most memorable moments in our teaching careers had less to do with us than the experiences we arranged for our students. Most of those experiences required an artful use of resources—arranging for a Holocaust survivor to visit school, conducting an archaeological investigation at a local cemetery, or conducting authentic research.

One characteristic of effective teachers is knowing how to maximize the resources available to them. When effective teachers encounter new things, they begin to visualize how they might use them in their classes. The local retirement home becomes a source of local oral historical research; the river on the edge of town becomes data for a lesson on water pollution; a generic software program is transformed into a compelling game for students.

Textbooks

We begin by analyzing the most common and prominent resource in the K-12 classroom: the textbook. How can teachers squeeze the most from the textbooks they are provided?

Of course, there are lots of general criteria teachers use to evaluate their textbooks. Is the content organized well? Is the writing lively and interesting? Does the textbook use interesting, controversial, and relevant examples? Is the textbook visually appealing? Does the textbook provide multiple perspectives? Does the textbook invite higher levels of thinking? Is the textbook age appropriate?

Within each of your subject areas, you might also add additional criteria. For example, a teacher of civics and government may well decide that he or she is concerned with having a textbook that helps students conceptualize important ideas such as constitutionalism, democracy, human rights, representative government, and civil society. Watch a critique of textbook publishers below.

What general and subject-specific criteria do you expect from your textbooks?

How well do textbooks align with standards in your content area?

How will you use the textbook in your classroom?

Non-traditional Resources

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement:

“Non-traditional and new-media resources hold a great deal of promise to maximize student learning.”

Why?

As resources, all textbooks are incomplete. Even the best textbooks need to be supplemented with additional resources that bring ideas and skills to life. Watch the brief video below that describes how an anthropologist at DePaul University, Jane Baxter, transformed mobile technology and access to local cemeteries into deep learning for her students.

Speaking of resources, while you will certainly find some great ideas for decorating your classroom on share sites such as Pinterest, make sure you extend your search. Include sites with content supported by Common Core or state standards, research-based practices (look at the citations in the reference list), or activities created by curriculum specialists when looking for lesson- or behavior-based classroom activities.

However, if you do stumble across something that seems credible on Pinterest, follow up by clicking on the link and investigating the planning/preparation, purpose, and research behind the thumbnail image.

To get you started, here are a few examples of credible online sources to find curricular materials and activities:

- Readwritethink

- Smithsonian for Educators

- Kids Discover Online

- Annenberg Learning

- Brainpop

- Teaching Channel

Your Turn

Brainstorm a list of specific resources you might use with your students.

Lesson Planning

Although practicing teachers need to carefully plan courses and the units of instruction within each course, as beginning pre-service teachers, we will focus on the most basic component of planning: the lesson.

Like most other important issues in teaching and learning, there is no single, agreed-upon best model for lesson planning. Most teachers eventually develop their unique way of lesson planning. You may hear people talk about the Gagne Model or the Hunter Model or the 5E Model. . . . All of these models are based on some similar characteristics.

In Core Teaching Skills, we are asking that you use a simple and straightforward model of lesson planning that contains the following elements:

STANDARDS

OBJECTIVES

POSSIBLE QUESTIONS

MATERIALS

ACCOMMODATIONS

BEGINNING OF A LESSON

MIDDLE OF A LESSON

END OF A LESSON

Simple guidelines for each of these parts are provided below. You will find a template on our Canvas page. Keep in mind that the format will vary from professor to professor and district to district.

Core Teaching Skills

LESSON PLAN FORMAT

Kansas State University

STANDARDS:

- Write out (i.e., cut and paste) the specific Standards, Benchmarks, and Indicators the lesson will address.

- Choose 1 or 2 specific ideas or skills on which to focus the lesson.

- Make sure everything in the lesson focuses on these aspects of the standards.

OBJECTIVES:

- Write 1 – 3 clear, age-appropriate, standards-based objectives.

- Correct Example-The student will compare the colonists’ vs. British perspectives on the American Revolution.

- Incorrect Example-The student will read the chapter and discuss the American Revolution.

POSSIBLE QUESTIONS:

- Write 4-5 interesting, engaging, open-ended, and meaningful questions you might ask during the lesson.

MATERIALS:

- List all the materials required for instructing this lesson.

- Cite resources (basal publisher, website, children’s book) where applicable.

- Attach supporting documents (student handouts, overheads, examples, etc.) if they are available.

- Indicate how technology is used in planning and enhancing instruction.

- Do not list materials that are customary parts of the classroom (e.g., whiteboard)

ACCOMMODATIONS:

- In what ways will you adjust the lesson plan to the unique needs of individual learners?

- If you are planning a lesson prior to having students, how might you accommodate an individual learner?

- Note: A paraprofessional or another student is NOT an accommodation.

BEGINNING OF LESSON:

- Clearly describe how you will gain and focus student interest.

- Your goal is to create a “need to know.”

- This part of the lesson should last approximately 3-5 minutes.

MIDDLE OF LESSON:

- Instructional activities and assessment align with stated objectives.

- Key concepts are explained and/or modeled

- Elements of effective instruction are evident – such as:

- opportunities for students to practice, process or participate

- planned transitioning

- application of learning/assessment

- procedures are developed in[…]”

END OF A LESSON:

- Clearly describe what you and the students will do to close the lesson.

- A well planned and executed lesson ending asks students to demonstrate their knowledge or skills in some new way and allows the teacher to assess student achievement of the lesson objectives.”

Writing Objectives

Effective teachers are purposeful–they begin planning with a clear idea of what they want students to know, be able to do, or feel. Teachers write objectives at different levels of generality–course, unit, and lesson. Objectives or outcomes provide focus and clarity to student learning and help to guide instructional practice. Carefully planning for student learning by writing clear and challenging objectives, however, should not limit spontaneity, constrain creativity, or restrict the teacher’s ability to adjust instruction based upon assessment of student learning.

Types of Objectives/Outcomes

Two main types of learning objectives or outcomes exist–behavioral objectives and descriptive objectives. Behavioral objectives state what is to be learned in language that specifies observable behavior. An example of a behavioral objective at the level of lesson would be:

Given a list, students will be able to list five problems of government under the Article of Confederation with 100% accuracy.

Descriptive objectives clearly describe what students are to learn without using language that specifies observable behavior. An example of a descriptive objective at the level of lesson would be:

By the end of the lesson, students will explain the problems of government under the Articles of Confederation.

Depending upon the nature of the subject you teach, you may utilize both types of outcome statements to guide student learning and your teaching. However, descriptive objectives are most common and are the type we will use in CIA.

Objectives/Outcomes Across Domains of Learning

Although there are various ways to classify learning outcomes, one common way was developed by Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues (1956). Bloom classified learning outcomes into three types: cognitive (i.e., knowledge), psychomotor (i.e., skill), and affective (i.e., attitude). Typically, most K- 12 learning objectives are aimed at the cognitive and psychomotor domains.

Levels of Generality and Specificity

One of the challenges to writing clear and effective learning outcomes or objectives is selecting the appropriate level of generality or specificity. Course objectives are the most general statements of student learning; lesson objectives are the most specific; and unit objectives fall between the two extremes. It is important for teachers to be able to clearly and concisely express the outcomes of student learning at all three levels. The examples at the end of this handout illustrate these three levels.

Tips for Writing Effective Learning Objectives

Learning objectives/outcomes should. . .

- Be clear, easy to understand, and unambiguous;

- Guide the selection of content and pedagogy;

- Be written for student learning, NOT teacher behavior;

- Focus on the ends (i.e., goals), NOT the means (i.e., learning activities);

- Promote learning across various domains (i.e., knowledge, skills, and attitudes);

- Promote a range in levels of understanding and/or performance (e.g., higher-order thinking);

- Be relevant to the local curriculum and/or state standards;

- Be developmentally appropriate for the age and background of learners (e.g., both challenging and attainable); and

- Utilize active verbs.

Examples of Clear Learning Objectives

Course Objective (Psychomotor)

By the end of grade three, students will. . .

become more proficient thinkers, careful writers, critical readers, and better able to discuss important and controversial issues.

Unit Objective (Affective)

By the end of the unit, students will. . .

appreciate the importance of citizen participation in a democracy.

Lesson Objective (Cognitive)

By the end of the lesson, students will. . .

compare and contrast authority and responsibility.

Blooms Revised Taxonomy

One useful tool the teachers commonly use to think about and classify learning objectives and questions is Bloom’s revised taxonomy. Our Canvas page will have multiple versions of this.

Beginning/Middle/End of an Effective Lesson

Like a good burger, like a good movie, like a good basketball game, a good lesson…an effective lesson…has three main parts: Beginning, middle, and end.

And like a burger, a movie, and a basketball game, when you assemble all the right ingredients such as objectives, questioning approaches, and activities, you get an effective lesson.

So, to get us started, time travel again. How did your super-amazing/cool/effective teacher in elementary, middle, or high school start his or her lessons? With a thought-provoking question? Bell work? A brief introductory activity? Why was it successful? You may not have noticed at the time, but as you reflect upon it today, did those lessons include a distinctive beginning, middle, and end?

The Beginning

So, how do you start? What are your goals for the beginning?

• Get their attention

• Get them to put away their cell phones

• Get them to stop talking to their friends

• Get them motivated to learn

You need a solid beginning. Wasting time at the beginning of your lesson signals to the students that there is, indeed, time to waste. And, so they gladly help you waste it. Some of those time-wasters can be taking attendance or lunch count or handing out papers and other materials. You need a system to get those necessary tasks done efficiently and effectively without losing teaching time.

You also need some way of capturing student interest and focusing it on your learning objectives. All lesson plan models ask teachers to plan for a good beginning. Lesson introductions are also called “anticipatory sets” or the “lesson hook.”

Read Richard Curwin’s “Your Lesson’s First Five Minutes: Make them Grand” and watch the video below.

The Middle

Once you’ve established that class has begun and you’ve gotten their attention, you’ll be moving into the heart of your lesson–where students approach the content in full force…through activities to help them learn. Some principles are listed below:

Variety is important within and across lessons. Kids do not want to do the same thing every day or spend the entire class doing one thing. Lesson middles should include a variety of strategies and activities.

Research-based Teaching strategies are valuable components of any lesson. We will discuss here more thoroughly in Module 8, but you should considering how to incorporate:

- Identifying similarities and differences

- Summarizing and note taking

- Reinforcing effort and providing recognition

- Homework and practice

- Nonlinguistic representations

- Cooperative learning

- Setting objectives and providing feedback

- Generating and testing hypothesis

- Questions, cues, and advance organizers

Pacing can be an issue in the implementation of a lesson. The lesson can move too quickly or too slowly, and both can be equally problematic. Much like the fairy tale, “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” the pacing needs to be just right.

Staying task-oriented and ensuring learning time are key to helping your students move through the lesson smoothly while addressing the objectives you’ve established for that lesson. And that includes managing time and keeping students focused. Check out the video below for helpful tips and examples.

Transitions from one activity–or portion of an activity–to another can be another stumbling block in the middle of your lesson. It’s that transition time where students can waste time, get distracted with other things, or generally just not understand that time in a classroom is a valuable thing.

And, finally, don’t overlook the power of your own enthusiasm. Students want to know that you’re excited about the lesson, and they’ll reflect the enthusiasm they see in you…and the tone of your voice…and your facial expressions and body language.

The End…Sort Of

The thing about meaningful lessons is that they usually have meaningful endings. But how do you accomplish such an ending? The best lesson endings ask the students to demonstrate their new knowledge or skills in some novel way. Just like lesson beginnings, there is no one correct way to end a lesson. Think about some of the more accomplished teachers that you’ve had through the years. How did they wrap things up? How did they actively engage students and check for understanding?

Some possibilities:

- Lead a brief discussion on key ideas

- Ask students to write two interesting, open-ended questions that could be answered from material in the lesson.

- Have students present the results or a project or activity

Check out a teacher’s description of the end of the lesson, which is also known as lesson closure.

Questions

- What are some things you can do if you notice the pacing of your lesson is too fast and you’re going to end up with several minutes of idle time between the end of the lesson and the bell?

- What is one specific idea for beginning your future class? Why do you think it would be an effective way to start the class period?