3 Chapter 3: The Foundations of Education in the United States

Dr. Della Perez

The Foundations of Education in the United States

In order to understand our current educational practices, it is essential to look at the history of education in the United States. Therefore, this chapter will explore key events in the history of education and how these events impacted our present institutions, theories, and practices. After discussing key events in the history of education in the United States, a closer look at the “deculturalization” of specific groups will be explored.

Section I: History of Education

3.1 Essential Questions

By the end of Section I, the following essential questions will be answered:

- What was education like in Colonial America?

- What were key influences on the way the educational system was set up in Colonial America?

- Who helped to shape the educational philosophy of American schools between the 1700’s and the 1800’s?

- What did the curriculum look like in the first American Schools and how has it changed?

The need for a society to educate its’ young is universal in all cultures. How we educate is the question. For it is from how education is delivered that ideologies are revealed. Who should be educated and at what level is generally decided by those in authority. Questions about what should be taught and why are examined by society as it seeks to shape and and determine its culture.

In this section, we will briefly overview the history of American Education. Key points that will be covered in this historical overview include:

- Education in Colonial America

- Types of Schools

- Educational Philosophies

- Curriculum Considerations

Knowing this history will provide you with a solid foundation upon which to base your understanding of the evolution of the American Educational system.

Education in Colonial America

The first pilgrims settled in Plymouth (Massachusetts) in 1620. These pilgrims, a group of Separatist Puritans (or Protestants focused on purifying others as well as separating from the Church of England), were the first to establish a formal education system in Colonial America. Based on their Puritan views, the first schools established in Colonial America emphasized the religious beliefs of the Separatist Puritans. According to research by Johnson, Musial, Hall, and Gollnick (2011), the educational system in Colonial American was broken down into the following three colonies as the population grew:

- Northern Colonies: These colonies were made up of large tobacco plantations and utilized slaves from Africa to work on the plantations. The children of the wealthy landowners had private tutors to teach their children at home, and no education was provided to the children of the slaves. This ensured a level of knowledge and under- standing for those who were destined for leadership in courts, politics and state government, and the church.

- Middle Colonies: The settlers in these colonies represented various nationalities (i.e., Dutch, Swedish) and religions (i.e., Puritan, Mennonite, and Catholic). Given the range of backgrounds represented in this group, each group established their own religious schools. The children in these schools could be found learning through an apprenticeship (they learned a trade from a master al- ready in the line of work they wanted to pursue).

- New England Colonies: These colonies were mainly settled by Puritans and emphasized strong religious beliefs. How- ever, these schools were also located in places where an industrial economy demanded skilled and semiskilled workers. Therefore, the curriculum within these schools had to reflect the needs of this society.

3.2 A Closer Look

The following video provides and more in-depth look at the three colonies identified above. As you watch this video, consider the following questions:

- If you were a settler in Colonial America, which colony would you want to live in and why?

- What was the purpose of education/schooling in Colonial America?

- What “truth” was being taught to the students?

- Do you agree with this “truth?” Why of why not?

Types of Schools in Colonial America

There were different types of elementary schools in Colonial America. In this section, the Dame School and the Latin Grammar School will be described.

Dame Schools were the precursor to the primary school. Here, older

women, such as widows and housewives, would teach children the three R’s, frequently in the kitchen area of their homes. If girls were given any education, it was at a Dame School, and likely it was in sewing and homemaking skills. In all of the colonies, some boys were offered an education beyond what the Dame School and their parents could offer them. School for reading and writing were supported by parents, who paid fees if their children attended Dame Schools. The following pictures shows a typical activity that women in Dame Schools would be engaged in during school.

The Latin Grammar School was for those who were privileged enough to do well in school, and for those who came from families that could afford to continue their child’s education. Latin Grammar Schools were founded in 1635 and focused on a classical curriculum defined as the study of classical languages and literacy (primarily Latin and some Greek). The boys who attended Latin Grammar Schools continued onto the first college, Harvard (founded in 1636). After completing college, they went on to take leadership roles in the community, in the state, and often in government.

3.3 A Closer Look

For more information on Dame Schools and Latin Grammar Schools, watch the following video.

American schools in the 1700’s & 1800’s

Many great people helped shape the face of American Schools in the 1700‘s & 1800‘s. What follows is a brief overview of a few of these key people and the philosophical movements they began.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

Benjamin Franklin argued that all subjects should be taught in the English language to all students. He also advocated for a practical nature of learning to be included, so that skills taught in school would assist the young person later in life, in his or her daily life and work.

Franklin believed that education for the new society should include knowledge that would serve citizens in their endeavors. The schools he advocated for were called English Schools to differentiate them from Latin Grammar Schools. The central struggle in creating academies was between a classical curriculum and a practical curriculum.

- Should the school curriculum include traditional, classical subjects or should it include the day to day wisdom and practical skills people use in their everyday lives?

Thomas Jefferson (1743 – 1826)

Thomas Jefferson argued that only with educated people could a free government and foundation of democracy be secure. In order to participate in a self-governing democracy, its’ citizens had to be educated.

When Jefferson stated that “an informed population safe-guarded democracy,” his notion rested on people having access to schools, being able to read and write, and through reading and thinking, being able to judge the worth of political ideas. Education, then, had an explicit political purpose in terms of defining and enacting democracy. For Jefferson, the integration of education and government became the theme of many of his writings.

When Jefferson stated that “an informed population safe-guarded democracy,” his notion rested on people having access to schools, being able to read and write, and through reading and thinking, being able to judge the worth of political ideas. Education, then, had an explicit political purpose in terms of defining and enacting democracy. For Jefferson, the integration of education and government became the theme of many of his writings.

He submitted the following amendment to the Constitution to Congress during his State of the Union Address on December 2, 1806:

Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers of the people alone. The people themselves are its only safe depositories. And to render even them safe, their minds must be improved to a certain degree…An amendment to our constitution must here come in aid of the public education. The influence over government must be shared among all people (as cited in Padover, 1939, p. 87).

The amendment did not pass Congress.

1. Why would the 1806 Congress not pass an amendment that funded public school education for all citizens in the new nation? Do you agree with their decision? Why or why not?

One reason was that the new Congress was composed of representatives from all of the 13 new states, all of which had experience with local control of education. Handing over responsibility to fund education to the central government also meant giving up control of what form schools, teachers, and the curriculum would take.

Horace Mann (1796 – 1859)

Horace Mann is often described as “the father of American Education.” Mann envisioned a universal public education available to all children in the country.

He believed passionately that education would bring about equality, and that through a public school system avail- able to all, the ideals of the Constitution could be realized. Through a system of public schools, all children, rich and poor, would be offered a primarily sectarian education to en- large their view of themselves and others in order to build a harmonious society. Through the gateway of education, equality for all would be available and poverty would cease. Furthermore, Mann was convinced that schools should teach a common set of beliefs and moral values to promote harmony among different groups. Mann believed that only social good would come from such an approach to public school education.

He believed passionately that education would bring about equality, and that through a public school system avail- able to all, the ideals of the Constitution could be realized. Through a system of public schools, all children, rich and poor, would be offered a primarily sectarian education to en- large their view of themselves and others in order to build a harmonious society. Through the gateway of education, equality for all would be available and poverty would cease. Furthermore, Mann was convinced that schools should teach a common set of beliefs and moral values to promote harmony among different groups. Mann believed that only social good would come from such an approach to public school education.

The movement to provide universal education and schools that would serve all children at public expense was known as the common school movement. The common school movement in the early part of the 1800s was a mile- stone in the United States. In Mann’s democratic experiment, education came to be viewed as a significant way of ensuring a universally informed citizenry, people who would participate in local and national politics with understanding of broad issues.

1. Do you agree with Horace Mann and his vision for universal public education available to all children? Why or why not?

2. Do you think the American people were right to resist the idea of a common, universal education at the time it was proposed by Mann? Explain.

3. Do you think the ideals of his approach are in place? Please provide a specific example.

Industrialization

As the new nation moved into the industrial era, rural communities became more closely tied with their urban counter-parts. More trade and the increased demand for goods and services reflected a society that was experiencing great social change.

Rural areas became part of a roadway to transport agricultural goods and materials to growing towns. These rural communities were exposed to new ideas and new opportunities that shifted their once closed circle. Further, industrialization required more and more labor. Jobs for those who were willing to leave their homes and venture into factories brought new demands. What was once a closed community, where work was done in the home, and home was the place where one worked, now separated the two; work and home became distinct from one another.

Immigration

New immigration in the mid-to-late 1800s fueled industrialization. The development and expansion of common schools existed alongside unprecedented levels of immigration and in a context of rapid industrialization. This meant that the numbers of students in schools was increasing rapidly as well. This change was most reflected in the nation’s urban school systems.

3.4 A Closer Look

To better understand the increase in population, where our immigrant population came from, and

how it had an impact on this population, please watch the following video.

Efficiency Movement

Another educational development at the intersection of common schooling and industrialization was the efficiency movement. This educational approach emerged from the influence of Frederick Taylor, who believed that the way to make factories more profitable was to make them more efficient. This efficiency movement influenced public schools, especially schools that had large populations of poor, working-class students, many of whom were immigrants. Students were taught in ways that would prepare them to enter the workforce as new industries and factories required workers to follow directions, be punctual, and do the work.

The express purposes of these schools were to:

• enculturate new immigrants,

• teach them to speak and understand English,

• help them learn how to adapt to the customs of their new country

• help them learn to be good workers.

Schools were essentially following the factory model, and an efficiency model that emphasized conformity, following directions, rote learning and memorization, and strict rule comportment.

Individually reflect on the information you learned about the history of education in the United States. Take a moment to respond to the following questions on a blank sheet of paper.

1. What did you learn about the history of American schools by reading and watching the videos provided in this section?

2. What is one fact that surprised you the most?

3. Where do you think we stand today when it comes to American Education?

Section II: Deculturalization – The History You May Not Know

3.5 Essential Questions

At the end of this section, the following questions will be answered:

-

- What is “deculturalization” and how does it impact education?

- What are specific

examples of “deculturalization” experienced by each of

the following groups:A. Native Americans B. African Americans

C. Asian Americans

D. Mexican Americans - How do you think the examples of deculturalization experienced by each group might impact your future teaching?

The history of education in the United States has been plagued with violence and racism. Nowhere is this more evident in the racial clashes that have taken place over the education of Native Americans, African Americans, Asian Americans, and Mexican Americans. These racial clashes can be traced back to the colonial period, in which political equality and freedom were only intended for white, male Protestants (Spring, 2013).

In order to ensure that minority groups did not take away from the educational experiences of Anglo peers, they were subjected to different levels of deculturalization. Deculturalization, as defined by Spring (2013), is “the educational process of destroying a people’s culture (cultural genocide) and replacing it with a new culture” (p. 8). Unlike acculturation in which people from different cultural backgrounds maintain their culture and take on aspects of the new culture, deculturalization focuses on destroying the students cultural background entirely and assimilating them to majority culture.

- Can you think of one of more specific examples of deculturalization that have taken place among minority groups in American Schools?

- Do you think minority students still experience deculturalization? Why or why not?

- What will you do as a future teacher to address issues of deculturalization (historical and present day)?

The Struggle for Equality: Deculturalization in Practice

To better understand deculturalization and its’ impact on specific minority groups, let’s take a closer look at four groups who have experienced deculturalization:

- Native Americans

- African Americans

- Asian Americans

- Mexican Americans

Native Americans

From their first interactions throughout the later settlements moving west, the early settlers believed they had to “civilize” the indigenous peoples to the English way of life. Given the overtly religious nature of this primarily Protestant society, the first step toward civilization was conversion to Christianity. Mission schools were a common means of promoting this goal.

The treatment of the Native Americans by those who colonized the New World was based on the belief that differences were bad, so striking out all aspects of their native culture was the first step to eliminating their inferiority. Not only were missionaries committed to serving a “civilizing” role, but the eventual creation of boarding schools for Native American children emphasized eradicating indigenous culture and language.

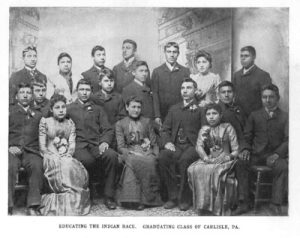

The first major boarding school was established by General Richard Pratt in 1879 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania (Webb, Metha, and Jordan, 2010). After the Civil War, all Native American children were sent to these boarding schools in order to assimilate them into the dominant culture and language. To facilitate their assimilation, they were given new names, forbidden to speak in their native language, and “dressed” to look more civilized (see the picture below for an example of the transformation the Native American students underwent at the boarding schools).

According to the National Congress of American Indians, there are approximately 644,000 American Indian and Alaska Native students in the US K-12 system, which makes up about 1.2 percent of public school students in the United States (NCES, 2018). Ninety percent of these students attend public schools, while eight percent attend Bureau of Indian Education schools.

3.6 A Closer Look

Watch the video for additional insight on the Native American boarding schools. As you watch the video, use the following “Questions to Consider” as a guide.

- As a future teacher, how will you make sure you are prepared to meet the needs of this student population?

- In what ways might you make sure their languages are represented and built upon in schools?

- In what ways might you make sure their cultures are recognized and celebrated in schools?

African Americans

African American children were generally bared from attending common schools, both in the north and

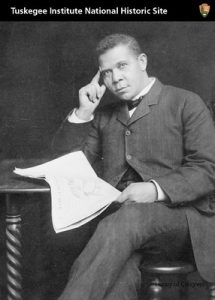

south. In 1850 the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled in Roberts v. City of Boston that separate, segregated schools were legal, leaving little choice for African Americans who desired education for their children but to send them to segregated schools. Furthermore, they were denied U.S. citizenship and political rights recognized in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision of 1857 (Spring, 2013). In order to provide African Americans with a more equal opportunity, Booker T. Washington founded the for African American students in 1880.

Another case that had a profound impact on African Americans was Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court stated that “segregation did not create a badge of inferiority if segregated facilities were equal and the law was reasonable” (Spring, 2013, p. 56). Even though this case was based on Homer Plessy’s refused to sit in a car for blacks, it sanctioned segregation in the following public facilities as well: buses, hotels, theaters, swimming pools and schools.

After the Civil War, African American leaders began to argue for equal access to education. Although minor progress was made throughout the years, it was not until the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) that segregation in public schools became unconstitutional.

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act also had a profound impact on the education of African American students.This impact was based on the following:

- Title VI: This portion of the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination against students on the basis of race, color, or national origin when receiving federal funds.

- Title VII: Forbids discrimination in employment based on race, religion, national origin or sex.

According to a study by the U.S. Department of Education (2018), only 73 percent of African Americans complete high school vs. 87 percent of white students.

As a future teacher, how will you act as an advocate for your African American students in and out of the classroom?

3.7 A Closer Look

Please watch the following video for an overview of key events in the history of the Civil Rights Movement. As you watch the video, please think about the following “Questions to Consider:”

- How many of the events discussed in the video did you learn about in school?

- What was the most shocking event you learned about?

- Why do you think the rights of African American’s were denied for so long?

- Do you think African American students still struggle in today’s society? Why or why not?

- How will you advocate for these students in your future classroom?

Asian Americans

Asian Americans were often economically exploited by the Anglo-American population, who perceived them to be immoral, and racially and culturally inferior. Even through they came to the United States in pursuit of a better life and the promise of naturalization, laws like the Chinese Exclusion Law (1943) denied specific Asian populations like the Chinese the right to become naturalized citizens (Spring, 2013).

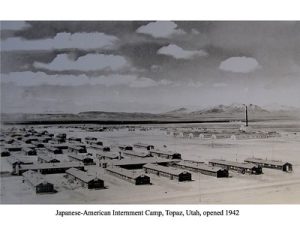

However, one of the most shocking examples of the dis- regard for citizenship status took place within the Japanese-American population during the Second World War. During the war, over 100,000 Japanese Americans were placed in internment camps. In some cases, they were forced to leave their property with little notice or it was confiscated (Johnson et. al., 2011). In 1990, the U.S. government officially apologized to this population and offered to pay restitution for lost property.

3.8 A Closer Look

To learn more about the “deculturalization” of Japanese Americans, watch the following video. Please use the “Questions to Consider” as a guide to help you process the video.

1. What did you know about the Japanese-American internment camps before this class?

2. Were you surprised by the way in which families where notified and transported to the camps?

3. How did the internment camps enhance deculturalization by removing this population from their homes and everything they owned?

4. Do you think the internment camps were necessary, why or why not?

Although life has improved for Asian Americans in the United States, one of the challenges this population still faces today is the “Model Minority” myth. This myth emerged in the 1960’s and proposes the following:

“Asians are the racial minority group that managed to prosper in the U.S. through hard work and education, hence setting an example for other marginalized racial groups to follow” (Reynoso, 2018, p. 1).

However, this myth was actually perpetuated by corporate media and historically is not valid. As demonstrated by the 1860 banning of Asians from public schools in California and the internment of Japanese-Americans under US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1942 during WWII.

As a future teacher, how will you make sure you are not thinking about your Asian students as “Model Minorities?” How might you also educate others about this myth so that your future Asian American students are not labeled in this manner?

Mexican Americans

Patterns of segregation also characterized the educational experience of Hispanic American children. After theMexican American War in 1848, Mexican American children were sent to segregated schools in order to assimilate them into white culture. Key to this assimilation was they elimination of their native language, a challenge that continues today with English-only legislation in states with large Hispanic student populations.

In 1929, key representatives from various Mexican American organizations formed the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). One of the main goals of this organization was to fight the discrimination of Mexican Americans, particularly when it came to school segregation (Spring, 2013). The case that had a profound impact on Mexican Americans was Mendez v. Westminster. In 1946, this case prohibited segregation in California’s public schools.

The historical root of unequal education and the devaluing of the culture and language of Hispanic American children can be seen in early educational practices. Issues related to parents’ immigrant and socioeconomic status, as well as their lack of knowledge about the U.S. education system, continue to lead to this groups deculturalization. With the Mexican American student population in U.S. public schools climbing to over 8 million, the establishment of policies that promote equity and respect for this student population has never been more crucial.

3.9 A Closer Look

The following video provides a broad overview of the historical and current challenges the group still faces today. As you view the video, please use the “Questions to Consider” to support you in critically reflecting on the experiences of this population.

1. What are the key issues that Mexican Americans, Hispanics, and/or Chicanos face in American schools?

2. Do you think this student population should speak English only? Why or why not?

3. How does the stripping of students’ native languages perpetuate deculturalization?

4. What are the advantages of maintaining students’ native languages?

A Final Look At Deculturalization

This section provided a close up look at deculturalization and the impact it has had on four specific student populations. As an educator, it is important to be aware of all the different ways in which deculturalization can take place in schools so we can actively advocate against them. Spring (2010) provides the following examples of specific methods of deculturalization that can take place in education:

- Segregation and isolation.

- Forced change of language.

- Curriculum content that reflects culture of dominant group.

- Textbooks that reflect the culture of the dominant group.

- Denial of cultural and religious expression by dominated groups.

- Use of teachers from the dominant group (p. 106).

Take a moment to reflect on the list above. Have you experienced or seen any of the specific methods of deculturalization described above? Which one(s)? What was the context and how would you react as a future teacher if put in the same situation? If you have never experienced any of the methods of deculturalization described above, do you think they still exist today? Why or why not? Once again, consider how you might address one or more of these methods of deculturalization if you experienced them as a student or future teacher.

3.10 Student Voices

As we leave this section, I would share some insights from a couple of your fellow KSU students.

“It is by learning from the United States history that, as a future educator, I can be aware of the impacts cultural genocide can have on a people group and strive to never emulate it.” CMU16

“I am an African American and I could not imagine being denied an education. I am very thankful to people like Sarah Roberts’ dad, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, etc for standing up for equal rights.” CBU16

“Future educators, we CAN make a difference. Stop deculturalization by being the change agents in our home, classrooms, and communities. Please be open to learn or open to teach us. Don’t make it about the ‘me’; make it about the ‘us’!” KB U16

As you leave this section, critically reflect on all you have learned about deculturalization. Write down three things you learned and three plans you have for the future to proactively address deculturalization so that it does not happen in your future classroom/school.

References

Ferlazzo, L. (2019, April 21). Response: Meeting the needs of Native American students. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-response-meeting-the-needs-of-native-american-students/2019/04

Jeung, R., Yellow Horse, A. J., & Cayanan, C. (2021, March 31). Stop AAPI Hate National Report. Stop AAPI Hate. https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Stop-AAPI-Hate-Report-National-210506.pdf

Johnson, J. A., , Musial, D, Hall, G. E., and Gollnick, D. M. (2011). Foundations of American Education: Perspectives on Education in a Changing World (15th Edition). Pearson.

Jefferson, T. & Padover, S.K. (Editor). Democracy by Thomas Jefferson. D, Appleton Century Crofts.

National Center for Education Statistics (2018). The condition of education. National Center for Education Statistics.

Reynoso, V. (2018, May 10). History of the Model Minority Myth in the US. CounterPunch. https://www.counterpunch.org/2018/05/10/history-of-the-model-minority-myth-in-the-us/

Spring, J. (2013). American Education (16th Edition). McGraw-Hill Education.

United States Department of Education. (2018, March). Trends in High School Dropout

and Completion Rates in the United States: 2014. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018117.pdf

Webb, L. D., Metha, A., & Jordan, K. F. (2010). Foundations of American Education. Pearson Merrill.