2 Chapter 2: The Social Foundations of Education

Dr. Della Perez

The Social Foundations of Education

Across the United States, the tapestry of the K-12 student population has changed dramatically over the last twenty years and is continuing to evolve. As a future teacher, it is important to think about your future student population. The reason for this is that each student has a different background and upbringing (biography). The more teachers know about each students biography, the better equipped they are to meet their educational, social and emotional needs. This chapter will explore key issues related to diverse student populations. In addition, we will explore key considerations for how you can equalize education within your future classroom so you can meet the needs of all your students. Finally, we learn a specific strategy to learn about your future students individual biographies.

Section I: Diversity in Education

2.1 Essential Questions

By the end of this section, the following essential questions will be answered:

- What does it mean to say our classrooms are “culturally diverse?”

- In what ways are students educational experiences impacted based on their socioeconomic status?

- How steps can we take to helps students from diverse backgrounds to obtain the same academic achievement levels as their peers?

There a many things to think about when it comes to diversity in education. This section will explore just a few of them, starting with cultural diversity within the United States. After which, we will compare these national statistics with the State of Kansas. Equally important in this section is social class and the impact it has on education. Finally, this section will examine the academic achievement gap linked to cultural diversity and social class differences.

Cultural Diversity

When you hear the term cultural diversity, what comes to mind? For some people, it is tied to racial differences. Others might think of differences based on ethnicity. Cultural diversity is indeed tied to race and ethnicity, but it also includes other elements as well. To better understand this, lets start with an quick review of terminology as presented by National Education Association (2021).

- Culture: A set of values, beliefs, or behaviors shared by a group of people based on race, geograpy, socioeconomic status, experiences, or other unifying factors.

- Diversity: Differences based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, class, age, country of origin, education, religion, geography, physical or cognitive abilities.

- Discrimination: Treatment of an individual or group based on their actual or perceived membership in a social category, usually used to describe unjust or prejudicial treatment on the grounds of race, age, sex, gender, ability, socioeconomic class, immigration status, national origin, or religion.

- Ethnicity: A socially constructed grouping of people based on culture, tribe, language, national heritage, and/or religion.

- Equity: Equity means fairness and justice and focuses on outcomes that are most appropriate for a given group, recognizing different challenges, needs, and histories.

- Implicit bias/unconscious bias: Attitudes that unconsciously affect our decisions and actions.

- Privilege: A set of advantages systemically conferred on a particular person or group of people.

- Race: More of a biological classification, based on physical and genetic variation. It is important to note that racial categories do not have a scientific basis but they do impact how an individual is perceived and may be used as a basis for discrimination and racial profiling.

- Racism: Historically rooted system of power hierarchies based on race — infused in our institutions, policies and culture — that benefits white people and hurts people of color.

- Stereotype: Characteristics ascribed to a person or groups of people based on generalization and oversimplification that may result in stigmatization and discrimination.

Although this is not a comprehensive list of terms, they do provide a strong overview of key elements educators should consider when it comes to cultural diversity. The terms that are more asset driven (in that they focus on the positive elements of cultural diversity) are: culture, diversity, ethnicity, equity, and race. The terms which are more deficit in their approach (in that they promote negative views of cultural diversity) are: discrimination, implicit bias/unconscious bias, racism, and stereotype.

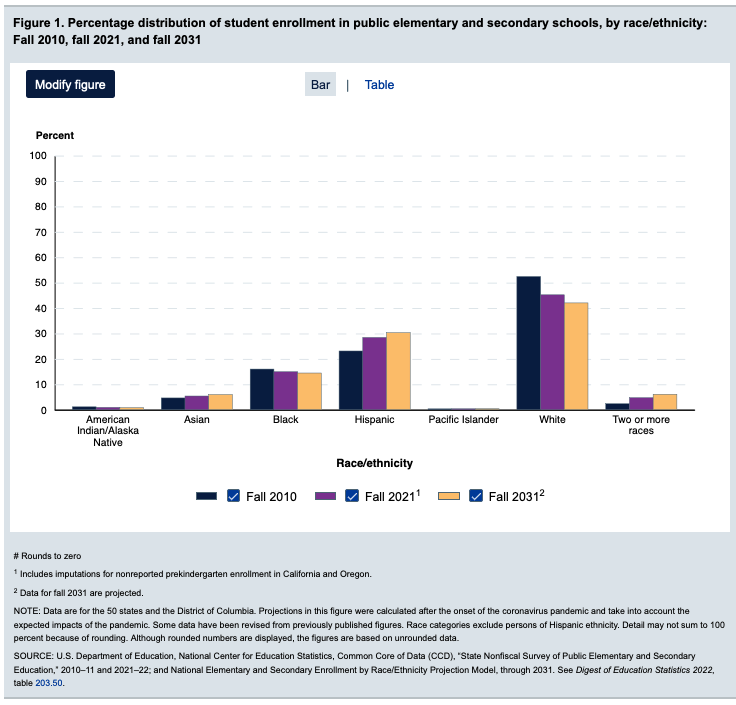

Whether you work in a large urban school district or a small rural district, you will work with culturally diverse students at some point in your teaching career. The following chart provides a breakdown of racial/ethnic student enrollment within the United States.

As demonstrated by this chart, there was a national growth in Hispanic, Asian, and Two or more races enrollment between fall 2010 and fall 2021. This growth is projected to continue over the next ten years. Perhaps what is most shocking data within this chart is the decline in White student enrollment from 52 percent in fall 2010 to 45 percent in fall 2021.

Within the State of Kansas, K-12 student demographics a similar to national trends with a few key differences. In 2000, the White student population in Kansas was 84%, declining to 62% in 2022. The Black student population grew less than one percent during this same time period. Most noteworthy is the increase in the Hispanic student population, jumping from just 7% in 2000 to 21% in 2022. This dramatic increase makes Kansas one of the fastest growing states in terms of its student diversity.

2.2 A Closer Look

- Do you think there is an issue with the percentage of public school teachers in Kansas who are White?

- What are some of the benefits of diversifying the teaching population in Kansas?

- What are some of the recommendations being made to within the article? Do you agree with these recommendations, why or why not?

Diversifying the teacher workforce will benefit Kansas students [https]

Social Class

The previous section explored cultural diversity and what it means. Closely tied to cultural diversity is class diversity. According to the NCES (2023), 17% of children in the United States under age 18 were classified as living in poverty in 2021. These poverty rates were higher than the national average for the following race/ethnic groups: American Indian/Alaska Native (32%), Black (31%), and Hispanic (23%). In Kansas, the percentage of students impacted by poverty was 43% in 2022 (KSDE, 2023).

To better understand why the meaning of these statistics it is important to look at the research. According to the NCES (2023), children’s academic achievement and overall educational experience are closely tied to their families socioeconomic status. Below, we will examine a few of the key reasons for these challenges.

Redlining stems from a form of illegal lending discrimination by banks used primarily against Black and Hispanic homebuyers. For many decades, redlining was used in conjunction with racially restrictive covenants as a way of keeping non-White citizens out of certain neighborhoods and perpetuating segregation. (Woodard, 2022). The impact redlining has on education is that the quality of a public school tends to increase in proportion with the Zip code’s income bracket. Redlined neighborhoods, which contain predominantly non-white school districts, receive 23 billion less in funding (Mar-Shall, 2021). Tenured teachers (those with more teaching experience), tend to work in more affluent schools that are not located in redlined areas. The lack of tenured teachers and teacher who transfer out of redlined schools more quickly negatively impact the quality of the curriculum student receive.

Equally challenging for children identified as living in poverty is access to resources. This is due in large part to funding differences between schools. Money distribution for schools is tied closely to the income bracket within each school district. According to NCES (2023), families in higher income brackets provide educational tools and opportunities to children in a variety of ways, including exposure to enrichment activities and technology. However, families living in poverty do not have the same resources to provide enrichment activities and technology. Research by Haider (2021) found that the pandemic worsened the barriers to quality education for low-income children given lack of access to technology in the home and/or internet access. In addition, the pandemic pushed parents, particularly mothers, to choose between working or taking care of their kids and helping with their education.

Another significant challenge for children living in poverty is directly tied to parents lack of familiarity with the educational system. Consequently, they are not able to advocate for their children in the same way a parent who is familiar with the system. Research by NCES (2023) shows a direct correlation to living in poverty with lower parental educational attainment. In adddition, children living in a single-parent household have a higher risk of low achievement scores, having to repeat a grade, and dropping out of high school (NCES, 2023). The cycle of poverty is extremely hard to break. One of the best ways to break this cycle is to ensure all children have equal opportunities and access to the same resources in school. However, as this section has show, this is not the reality.

2.3 A Closer Look

Please watch the following video for more insight into the effects of poverty on children. Note, the video does highlight specific steps being taken in Arizona – but the information is relevant across the United States. As you watch the video, please consider the following questions:

- What are some of the consequences on student outcomes for students in poverty?

- What are some of the the impacts on students dealing with the stress of poverty and how might this impact their behavior in the classroom?

- What are some of the resources/basic necessities that families in poverty are lacking? What are some of the consequences of this?

- What does it mean to have a better vocabulary about poverty? What is deep poverty and how is that different than poverty?

- What are some specific strategies teachers can use in the classroom to help students in poverty?

Section II: Equalizing Education

2.4 Essential Questions

By the end of this section, the following essential questions will be answered:

- What is ACEs? Why is this so important to be aware of as a future teacher?

- What is CRT?

- What are some specific strategies you can implement in the classroom that promote CRT?

Section one of this chapter looked at key issues related to diversity in education. Specifically, the concept of cultural diversity and social class were examined. In this section, we will build on these issues and look at key considerations and strategies you can apply in your future classroom to support ALL students.

ACEs

The acronym ACEs stands for Adverse Childhood Experiences. ACEs are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years). Some examples of these traumatic events, according to research by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are:

- experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect

- witnessing violence in the home or community

- having a family member attempt or die by suicide

- not having enough food to eat

- experiencing homelessness or unstable housing

- experiencing discrimination

- living in environments that might undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding

- growing up in a household with substance use problems, mental health problems, and/or instability due to parental separation or household members being in jail or prison (CDC, 2024).

The reason ACEs are so important to consider as a future teacher is because one or more of the students in your future classroom will be experience one or more of these issues. According to the CDC (2024), approximately 64% of U.S. adults reported they had experienced at least one type of ACE before age 18, and nearly 1 in 6 (17.3%) reported they had experienced four or more types of ACEs.

ACEs are also closely linked to the cultural and social issues explored in section one. For example, children with ACEs might live in racially segregated neighboorhoods, attend under-resources schools, and/or experiences social determinants of health. More alarming is the toxic stress (extended or prolonged stress) caused by ACEs. Toxic stress from ACEs can negatively affect children’s brain development, immune systems, and stress-response systems which changes can affect children’s attention, decision-making, and learning (CDC, 2024).

The following information outlines the risk and protective factors associated with ACEs, as identified by the CDC (2024):

Risk Factors

Individual and Family Risk Factors

- Families experiencing caregiving challenges related to children with special needs (for example, disabilities, mental health issues, chronic physical illnesses)

- Children and youth who don’t feel close to their parents/caregivers and feel like they can’t talk to them about their feelings

- Youth who start dating early or engaging in sexual activity early

- Children and youth with few or no friends or with friends who engage in aggressive or delinquent behavior

- Families with caregivers who have a limited understanding of children’s needs or development

- Families with caregivers who were abused or neglected as children

- Families with young caregivers or single parents

- Families with low income

- Families with adults with low levels of education

- Families experiencing high levels of parenting stress or economic stress

- Families with caregivers who use spanking and other forms of corporal punishment for discipline

- Families with inconsistent discipline and/or low levels of parental monitoring and supervision

- Families that are isolated from and not connected to other people (extended family, friends, neighbors)

- Families with high conflict and negative communication styles

- Families with attitudes accepting of or justifying violence or aggression

Community Risk Factors

- Communities with high rates of violence and crime

- Communities with high rates of poverty and limited educational and economic opportunities

- Communities with high unemployment rates

- Communities with easy access to drugs and alcohol

- Communities where neighbors don’t know or look out for each other and there is low community involvement among residents

- Communities with few community activities for young people

- Communities with unstable housing and where residents move frequently

- Communities where families frequently experience food insecurity

- Communities with high levels of social and environmental disorder

Protective Factors

Individual and Family Protective Factors

- Families who create safe, stable, and nurturing relationships, meaning, children have a consistent family life where they are safe, taken care of, and supported

- Children who have positive friendships and peer networks

- Children who do well in school

- Children who have caring adults outside the family who serve as mentors/role models

- Families where caregivers can meet basic needs of food, shelter, and health services for children

- Families where caregivers have college degrees or higher

- Families where caregivers have steady employment

- Families with strong social support networks and positive relationships with the people around them

- Families where caregivers engage in parental monitoring, supervision, and consistent enforcement of rules

- Families where caregivers/adults work through conflicts peacefully

- Families where caregivers help children work through problems

- Families that engage in fun, positive activities together

- Families that encourage the importance of school for children

Community Protective Factors

- Communities where families have access to economic and financial help

- Communities where families have access to medical care and mental health services

- Communities with access to safe, stable housing

- Communities where families have access to nurturing and safe childcare

- Communities where families have access to high-quality preschool

- Communities where families have access to safe, engaging after school programs and activities

- Communities where adults have work opportunities with family-friendly policies

- Communities with strong partnerships between the community and business, health care, government, and other sectors

- Communities where residents feel connected to each other and are involved in the community

- Communities where violence is not tolerated or accepted

As you can see from the lists above, there are many factors to consider when it comes to the risk factors associated with ACEs. The good news is, there are also many protective factors that can be implemented to support students experiencing ACEs.

2.5 An Example in Practice

CRT

The acronym CRT stands for Culturally Responsive Teaching. CRT challenges the “deficit perspective” that is commonly associated with the academic failure many diverse students experience in schools based on what teachers believe they can and can’t do. Educators who implement CRT focus on the personal and cultural strengths of diverse students (their assets) and teaches to and through these experiences to enhance their academic success in the classroom. According to Gay (2018), CRT can be defined as “using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant and effective for them (p. 36).”

Dr. Geneva Gay is attributed as one of the first researchers to come up with term CRT. According to her research, CRT is validating and affirming because:

- It acknowledges the legitimacy of the cultural heritages of different ethnic groups, both as legacies that affect students’ dispositions, attitudes, and approaches to learning as worthy content to be taught in formal curriculum.

- It builds bridges of meaningfulness between home and school experiences as well as between academic abstractions and lived sociocultural realities.

- It uses a wide variety of instructional strategies that are connected to different learning styles.

- It teaches students to know and praise their own and one another’s cultural heritages.

- It incorporates multicultural information, resources, and materials in all the subjects and skills routinely taught in schools (Gay, 2018, p. 37).

As demonstrated by this list, CRT is more than just another acronym! However, in order for teachers to truly embrace and teach from this perspective, it is not just about understanding the cultural assets of their students. Educators must first “analyze their own cultural attitudes, assumptions, mechanisms, rules, and regulations that have made it difficult for them to teach these children successfully (Gay, 2018, p. 33). The next section provides you with a concrete way to reflect on your own cultural background so you can then identify and build on the cultural background of your students. Without exploring your own cultural biography, you will not be able to understand and embrace those of your students!

Section III: Autobiographical narratives

2.6 Essential Questions

At the end of Section I, the following questions should be answered:

- What is an Autobiographical Narrative?

- What is the role of an Autobiographical Narrative in the classroom?

- What information is most important to include in an Autobiographical Narrative? Why?

- How might you adapt Autobiographical Narratives if you wanted to apply them with K-12 students?

- What did you learn about your peers as a result of sharing your Autobiographical Narratives with each other?

Autobiographcial Narratives

Every student brings unique talents and skills to the classroom. As educators, it is our job to find out what these talents are so that we can build upon them within the classroom. According to Herrera (2010), “understanding the core aspects of each student is essential to the process of identifying the skills and knowledge that he or she brings to the classroom” (p. 7). Autobiographical narratives are one of the key tools that educators can use to learn about the core aspects of each individual student biography.

Autobiographical narratives pull from research on Biography Driven Instruction (BDI). Biography-Driven Instruction (Herrera, 2016) is a communicative method of teaching and learning the helps teachers understand and maximize assets of the student biography to provide a more culturally responsive approach to teaching. For more information on BDI, please read the following article titled:

2.7 A Closer Look

The following article provides an in depth look at the following four key dimensions of Biography-Driven Instruction: sociocultural, linguistic, academic and cognitive. As you read the article, please consider the following questions:

- How does CRTP promote an asset-based perspective on teaching and learning?

- What is the purpose of each of the following phases of BDI: activation phase, connection phase, and affirmation phase?

- Which level of the ARS do you think is most important? Why?

- Which of the five themes in participants’ perceptions of BDI processes and outcomes did you find most powerful? Why?

Approximating Cultural Responsiveness: Teacher Readiness for Accommodative, Biography-Driven Instruction [https]

Creating Autobiographical Narratives

When creating autobiographical narratives, it is essential to consider the student population for whom you wish to apply the narratives with, as this will largely influence the design of your narrative. For example, students at the Kindergarten level will need a much different autobiographical narrative than students in 12th grade. In addition, you will want to think about how much information you would like to gather directly from the students. Depending on the age, needs, and even language proficiency levels of your students, some autobiographical narratives can be added to/completed by parents or primary caregivers.

Once you have established these basic parameters, you will want to determine what information you would like to gather. This information can range from very general to very specific. A good recommendation is that you try to gather information about each of the following four dimensions of the students biography:

- Sociocultural (SC)

- Who are the people in their family?

- Where were they born?

- Where were they raised?

- Who are the most important people in their lives?

- Linguistic (LG)

- What is their first language?

- What is their second language?

- What do they consider their strengths/weaknesses to be when it comes to language?

- Academic (AC)

- Where did they go to school?

- What special programs were they involved in at school?

- Did they participate in any sports?

- What did they like most/least about school?

- Cognitive (COG)

- What is the students learning style?

- What do they consider their strengths when it comes to learning?

- What do they struggle with when it comes to studying?

As part of this course, you are going to be asked to complete your own Autobiographical Narrative. When creating your Autobiographical Narrative, please keep these four dimensions in mind. Each dimension plays a critical role in defining who you are as an individual and future teacher.

2.8 An Example in Practice

Applying Autobiographical Narratives

Using insights gleaned from students autobiographical narratives, teachers have the knowledge they need to make critical adaptations to their instructional practices to better meet the needs of their student populations. A few of these adaptations have been identified below based on the potential information that could have been learned about the four dimensions of the student biography.

- Sociocultural (SC)

- Invite family members in to share information about their cultural background.

- Ask a family member to share expertise related to their professional practices.

- Have the student share information about another city, state, or country they may have lived in and/or traveled to at some point in their lives.

- Linguistic (LG)

- Have students use their first language to promote development/transfer as they acquire English.

- Provide specific interventions for students to help them address areas where they may be struggling.

- Capitalize on students “strengths” and make them language models for the class.

- Academic (AC)

- Build on prior academic experiences to support new learning in the classroom.

- Promote active engagement in school activities, sports, and/or other programs.

- Cognitive (COG)

- Incorporate multiple learning styles.

- Provide learning strategies to support students in and outside the classroom setting.

These are just a few ways you can apply the information learned from autobiographical narratives in the classroom.

Individually brainstorms some additional ways you might use the information from autobiographical narratives. Write down at least three ideas on a separate sheet of paper.

References

Anderson, T., Portillo, S., and Jordan D. (2022, August 30). Diversifying the teacher workforce will benefit Kansas students. Kansas Reflector. https://kansasreflector.com/2022/08/30/diversifying-the-teacher-workforce-will-benefit-kansas-students/

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 8). About Adverse Childhood Experiences. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice (Multicultural Education Series) (3rd Edition). Teachers College Press.

Haider, A. (2021, January 12). The basic facts about children in poverty. CAP. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/basic-facts-children-poverty/

Herrera, S. (2016). Biography-driven culturally responsive teaching (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Kansas State Department of Education. (2023). Kansas Report Card. KSDE. https://ksreportcard.ksde.org/home.aspx?org_no=State&rptType=3.

Mar-Shall, T. (2021, October 19). Redlining and the US educational system. Law Journal for Social Justice. https://lawjournalforsocialjustice.com/2021/10/19/redlining-and-the-us-education-system/.

NEA Center for Social Justice. (2021, January). Racial justice in education: Key terms and definitions. National Education Association. https://www.nea.org/professional-excellence/student-engagement/tools-tips/racial-justice-education-key-terms-and.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data (CCD), “State Nonfiscal Survey of Public Elementary and Secondary Education,” 2010–11 and 2021–22; and National Elementary and Secondary Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity Projection Model, through 2031. See Digest of Education Statistics 2022, table 203.50.

Woodard, D. (2022, May 6). What is redlining? The Balance. https://www.thebalancemoney.com/definition-of-redlining-1798618.