1 Defining Teams and Groups

Characteristics of Small Groups

Different groups have different characteristics, serve different purposes, and can lead to positive, neutral, or negative experiences. While our interpersonal relationships primarily focus on relationship building, small groups usually focus on some sort of task completion or goal accomplishment. A college learning community focused on math and science, a campaign team for a state senator, and a group of local organic farmers are examples of small groups that would all have a different size, structure, identity, and interaction pattern.

Size of Small Groups

There is no set number of members for the ideal small group. A small group requires a minimum of three people (because two people would be a pair or dyad), but the upper range of group size is contingent on the purpose of the group. When groups grow beyond fifteen to twenty members, it becomes difficult to consider them a small group based on the previous definition. An analysis of the number of unique connections between members of small groups shows that they are deceptively complex. For example, within a six-person group, there are fifteen separate potential dyadic connections, and a twelve-person group would have sixty-six potential dyadic connections (Hargie, 2011). As you can see, when we double the number of group members, we more than double the number of connections, which shows that network connection points in small groups grow exponentially as membership increases. So, while there is no set upper limit on the number of group members, it makes sense that the number of group members should be limited to those necessary to accomplish the goal or serve the purpose of the group. Small groups that add too many members increase the potential for group members to feel overwhelmed or disconnected.

Structure of Small Groups

Internal and external influences affect a group’s structure. In terms of internal influences, member characteristics play a role in initial group formation. For instance, a person who is well informed about the group’s task and/or highly motivated as a group member may emerge as a leader and set into motion internal decision-making processes, such as recruiting new members or assigning group roles, that affect the structure of a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Different members will also gravitate toward different roles within the group and will advocate for certain procedures and courses of action over others. External factors such as group size, task, and resources also affect group structure. Some groups will have more control over these external factors through decision making than others. For example, a commission that is put together by a legislative body to look into ethical violations in athletic organizations will likely have less control over its external factors than a self-created weekly book club.

Group structure is also formed through formal and informal network connections. In terms of formal networks, groups may have clearly defined roles and responsibilities or a hierarchy that shows how members are connected. The group itself may also be a part of an organizational hierarchy that networks the group into a larger organizational structure. This type of formal network is especially important in groups that have to report to external stakeholders. These external stakeholders may influence the group’s formal network, leaving the group little or no control over its structure. Conversely, groups have more control over their informal networks, which are connections among individuals within the group and among group members and people outside of the group that aren’t official. For example, a group member’s friend or relative may be able to secure a space to hold a fundraiser at a discounted rate, which helps the group achieve its task. Both types of networks are important because they may help facilitate information exchange within a group and extend a group’s reach in order to access other resources.

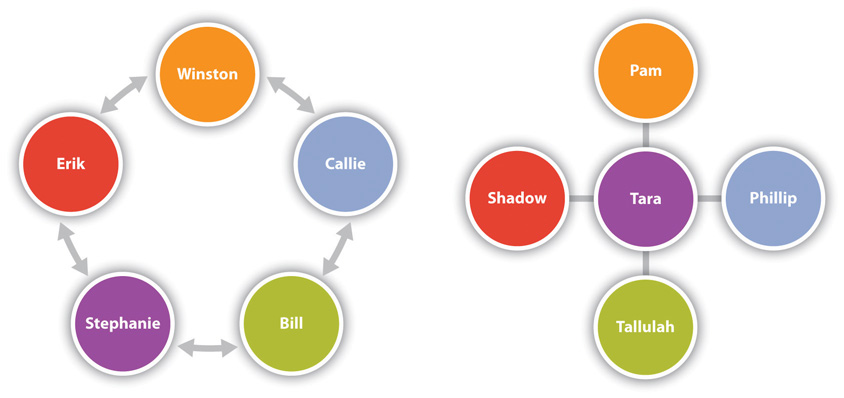

Size and structure also affect communication within a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). In terms of size, the more people in a group, the more issues with scheduling and coordination of communication. Remember that time is an important resource in most group interactions and a resource that is usually strained. Structure can increase or decrease the flow of communication. Reachability refers to the way in which one member is or isn’t connected to other group members. For example, the “Circle” group structure in Figure 1 shows that each group member is connected to two other members. This can make coordination easy when only one or two people need to be brought in for a decision. In this case, Erik and Callie are very reachable by Winston, who could easily coordinate with them. However, if Winston needed to coordinate with Bill or Stephanie, he would have to wait on Erik or Callie to reach that person, which could create delays. The circle can be a good structure for groups who are passing along a task and in which each member is expected to progressively build on the others’ work. A group of scholars coauthoring a research paper may work in such a manner, with each person adding to the paper and then passing it on to the next person in the circle. In this case, they can ask the previous person questions and write with the next person’s area of expertise in mind. The “Wheel” group structure in Figure 1 shows an alternative organization pattern. In this structure, Tara is very reachable by all members of the group. This can be a useful structure when Tara is the person with the most expertise in the task or the leader who needs to review and approve work at each step before it is passed along to other group members. But Phillip and Shadow, for example, wouldn’t likely work together without Tara being involved.

Looking at the group structures, we can make some assumptions about the communication that takes place in them. The wheel is an example of a centralized structure, while the circle is decentralized. Research has shown that centralized groups are better than decentralized groups in terms of speed and efficiency (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). But decentralized groups are more effective at solving complex problems. In centralized groups like the wheel, the person with the most connections, person C, is also more likely to be the leader of the group or at least have more status among group members, largely because that person has a broad perspective of what’s going on in the group. The most central person can also act as a gatekeeper. Since this person has access to the most information, which is usually a sign of leadership or status, he or she could consciously decide to limit the flow of information. But in complex tasks, that person could become overwhelmed by the burden of processing and sharing information with all the other group members. The circle structure is more likely to emerge in groups where collaboration is the goal and a specific task and course of action isn’t required under time constraints. While the person who initiated the group or has the most expertise in regards to the task may emerge as a leader in a decentralized group, the equal access to information lessens the hierarchy and potential for gatekeeping that is present in the more centralized groups.

Interdependance

Small groups exhibit interdependence, meaning they share a common purpose and a common fate. If the actions of one or two group members lead to a group deviating from or not achieving their purpose, then all members of the group are affected. Conversely, if the actions of only a few of the group members lead to success, then all members of the group benefit. This is a major contributor to many college students’ dislike of group assignments, because they feel a loss of control and independence that they have when they complete an assignment alone. This concern is valid in that their grades might suffer because of the negative actions of someone else or their hard work may go to benefit the group member who just skated by. Group meeting attendance is a clear example of the interdependent nature of group interaction. Many of us have arrived at a group meeting only to find half of the members present. In some cases, the group members who show up have to leave and reschedule because they can’t accomplish their task without the other members present. Group members who attend meetings but withdraw or don’t participate can also derail group progress. Although it can be frustrating to have your job, grade, or reputation partially dependent on the actions of others, the interdependent nature of groups can also lead to higher-quality performance and output, especially when group members are accountable for their actions.

Shared Identity

The shared identity of a group manifests in several ways. Groups may have official charters or mission and vision statements that lay out the identity of a group. For example, the Girl Scout mission states that “Girl Scouting builds girls of courage, confidence, and character, who make the world a better place” (Girl Scouts, 2012). The mission for this large organization influences the identities of the thousands of small groups called troops. Group identity is often formed around a shared goal and/or previous accomplishments, which adds dynamism to the group as it looks toward the future and back on the past to inform its present. Shared identity can also be exhibited through group names, slogans, songs, handshakes, clothing, or other symbols. At a family reunion, for example, matching t-shirts specially made for the occasion, dishes made from recipes passed down from generation to generation, and shared stories of family members that have passed away help establish a shared identity and social reality.

A key element of the formation of a shared identity within a group is the establishment of the in-group as opposed to the out-group. The degree to which members share in the in-group identity varies from person to person and group to group. Even within a family, some members may not attend a reunion or get as excited about the matching t-shirts as others. Shared identity also emerges as groups become cohesive, meaning they identify with and like the group’s task and other group members. The presence of cohesion and a shared identity leads to a building of trust, which can also positively influence productivity and members’ satisfaction.

What is a group?

Our tendency to form groups is a pervasive aspect of organizational life. In addition to formal groups, committees, and teams, there are informal groups, cliques, and factions.

Formal groups are used to organize and distribute work, pool information, devise plans, coordinate activities, increase commitment, negotiate, resolve conflicts and conduct inquests. Group work allows the pooling of people’s individual skills and knowledge, and helps compensate for individual deficiencies. Estimates suggest most managers spend 50 percent of their working day in one sort of group or another, and for top management of large organizations this can rise to 80 percent. Thus, formal groups are clearly an integral part of the functioning of an organization.

No less important are informal groups. These are usually structured more around the social needs of people than around the performance of tasks. Informal groups usually serve to satisfy needs of affiliation, and act as a forum for exploring self-concept as a means of gaining support, and so on. However, these informal groups may also have an important effect on formal work tasks, for example by exerting subtle pressures on group members to conform to a particular work rate, or as ‘places’ where news, gossip, etc., is exchanged.

What is a team?

Activity 1

Write your own definition of a ‘team’ (in 20 words or less).

Provide an example of a team working toward an achievable goals

You probably described a team as a group of some kind. However, a team is more than just a group. When you think of all the groups that you belong to, you will probably find that very few of them are really teams. Some of them will be family or friendship groups that are formed to meet a wide range of needs such as affection, security, support, esteem, belonging, or identity. Some may be committees whose members represent different interest groups and who meet to discuss their differing perspectives on issues of interest.

In this reading the term ‘work group’ (or ‘group’) is often used interchangeably with the word ‘team,’ although a team may be thought of as a particularly cohesive and purposeful type of work group. We can distinguish work groups or teams from more casual groupings of people by using the following set of criteria (Adair, 1983). A collection of people can be defined as a work group or team if it shows most, if not all, of the following characteristics:

- A definable membership: a collection of three or more people identifiable by name or type;

- A group consciousness or identity: the members think of themselves as a group;

- A sense of shared purpose: the members share some common task or goals or interests;

- Interdependence: the members need the help of one another to accomplish the purpose for which they joined the group;

- Interaction: the members communicate with one another, influence one another, react to one another;

- Sustainability: the team members periodically review the team’s effectiveness;

- An ability to act together.

Usually, the tasks and goals set by teams cannot be achieved by individuals working alone because of constraints on time and resources, and because few individuals possess all the relevant competences and expertise. Sports teams or orchestras clearly fit these criteria.

Activity 2

List some examples of teams of which you are a member – both inside and outside work – in your learning file.

Now list some groups. What strikes you as the main differences?

Your team examples probably highlight specific jobs or projects in your workplace, or personal interests and hobbies outside work. Teamwork is usually connected with project work and this is a feature of much work. Teamwork is particularly useful when you have to address risky, uncertain, or unfamiliar problems where there is a lot of choice and discretion surrounding the decision to be made. In the area of voluntary and unpaid work, where pay is not an incentive, teamwork can help to motivate support and commitment because it can offer the opportunities to interact socially and learn from others. Furthermore, people are more willing to support and defend work they helped create (Stanton, 1992).

By contrast, many groups are much less explicitly focused on an external task. In some instances, the growth and development of the group itself is its primary purpose; process is more important than outcome. Many groups are reasonably fluid and less formally structured than teams. In the case of work groups, an agreed and defined outcome is often regarded as a sufficient basis for effective cooperation and the development of adequate relationships.

Importantly, groups and teams are not distinct entities. Both can be pertinent in personal development as well as organizational development and managing change. In such circumstances, when is it appropriate to embark on teambuilding rather than relying on ordinary group or solo working?

In general, the greater the task uncertainty the more important teamwork is, especially if it is necessary to represent the differing perspectives of concerned parties. In such situations, the facts themselves do not always point to an obvious policy or strategy for innovation, support, and development: decisions are partially based on the opinions and the personal visions of those involved.

There are risks associated with working in teams as well. Under some conditions, teams may produce more conventional, rather than more innovative, responses to problems. The reason for this is that team decisions may regress towards the average, with group pressures to conform cancelling out more innovative decision options (Makin, Cooper, & Cox, 1989). It depends on how innovative the team is, in terms of its membership, its norms, and its values.

Teamwork may also be inappropriate when you want a fast decision. Team decision making is usually slower than individual decision making because of the need for communication and consensus about the decision taken. Despite the business successes of Japanese companies, it is now recognized that promoting a collective organizational identity and responsibility for decisions can sometimes slow down operations significantly, in ways that are not always compensated for by better decision making.

Is a team or group really needed?

There may be times when group working – or simply working alone – is more appropriate and more effective. For example, decision-making in groups and teams is usually slower than individual decision-making because of the need for communication and consensus. In addition, groups and teams may produce conventional rather than innovative responses to problems, because decisions may regress towards the average, with the more innovative decision options being rejected (Makin et al., 1989).

In general, the greater the ‘task uncertainty’, that is to say the less obvious and more complex the task to be addressed, the more important it will be to work in a group or team rather than individually. This is because there will be a greater need for different skills and perspectives, especially if it is necessary to represent the different perspectives of the different stakeholders involved.

Table 2 lists some occasions when it will be appropriate to work in teams, in groups or alone.

Table 2 When to work alone, in groups or in teams

| When to work alone or in groups | When to build teams |

| For simple tasks or problems | For highly-complex tasks or problems |

| When cooperation is sufficient | When decisions by consensus are essential |

| When minimum discretion is required | When there is a high level of choice and uncertainty |

| When fast decisions are needed | When high commitment is needed |

| When few competences are required | When a broad range of competences and different skills are required |

| When members’ interests are different or in conflict | When members’ objectives can be brought together towards a common purpose |

| When an organization credits individuals for operational outputs | When an organization rewards team results for strategy and vision building |

| When innovative responses are sought | When balanced views are sought |

Types of teams

Different organizations or organizational settings lead to different types of team. The type of team affects how that team is managed, what the communication needs of the team are and, where appropriate, what aspects of the project the project manager needs to emphasize. A work group or team may be permanent, forming part of the organization’s structure, such as a top management team, or temporary, such as a task force assembled to see through a particular project. Members may work as a group continuously or meet only intermittently. The more direct contact and communication team members have with each other, the more likely they are to function well as a team. Thus, getting a group to function well is a valuable management aim.

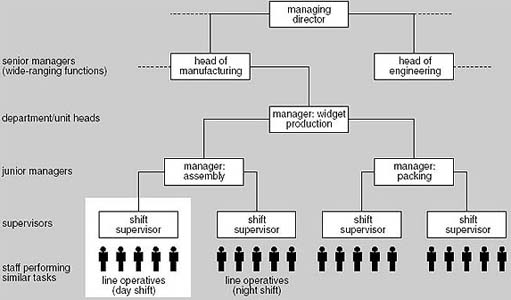

The following section defines common types of team. Many teams may not fall clearly into one type, but may combine elements of different types. Many organizations have traditionally been managed through a hierarchical structure. This general structure is illustrated in Figure 2, and consists of:

- staff performing similar tasks – grouped together reporting to a single supervisor;

- junior managers – responsible for a number of supervisors and their groups;

- groups of junior managers – reporting to departmental heads;

- departmental heads – reporting to senior managers, who are responsible for wide-ranging functions such as manufacturing, finance, human resources and marketing;

- senior managers – reporting to the managing director, who may then report to the Board.

The number of levels clearly depends upon the size and to some extent on the type of the organization. Typically, the ‘span of control’ (the number of people each manager or supervisor is directly responsible for) averages about five people, but this can vary widely. As a general rule it is bad practice for any single manager to supervise more than 7-10 people.

Figure 2: The traditional hierarchical structure. Note: The highlighted area shows one supervisor’s span of control: the people who work for that supervisor

While the hierarchy is designed to provide a stable ‘backbone’ to the organization, projects are primarily concerned with change, and so tend to be organized quite differently. Their structure needs to be more fluid than that of conventional management structures. There are four commonly used types of project team: the functional team, the project (single) team, the matrix team and the contract team.

Activity 3

Why is it problematic for a manager to supervise too many people? How does this relate to groups, is there an ideal group size or configuration?

The Functional Team

The hierarchical structure described above divides groups of people along largely functional lines: people working together carry out the same or similar functions. A functional team is a team in which work is carried out within such a functionally organized group. This can be project work. In organizations in which the functional divisions are relatively rigid, project work can be handed from one functional team to another in order to complete the work. For example, work on a new product can pass from marketing, which has the idea, to research and development, which sees whether it is technically feasible, thence to design and finally manufacturing. This is sometimes known as ‘baton passing’ – or, less flatteringly, as ‘throwing it over the wall’!

The project (single) team

The project, or single, team consists of a group of people who come together as a distinct organizational unit in order to work on a project or projects. The team is often led by a project manager, though self-managing and self-organizing arrangements are also found. Quite often, a team that has been successful on one project will stay together to work on subsequent projects. This is particularly common where an organization engages repeatedly in projects of a broadly similar nature – for example developing software, or in construction. Perhaps the most important issue in this instance is to develop the collective capability of the team, since this is the currency for continued success. People issues are often crucial in achieving this.

The closeness of the dedicated project team normally reduces communication problems within the team. However, care should be taken to ensure that communications with other stakeholders (senior management, line managers and other members of staff in the departments affected, and so on) are not neglected, as it is easy for ‘us and them’ distinctions to develop.

The matrix team

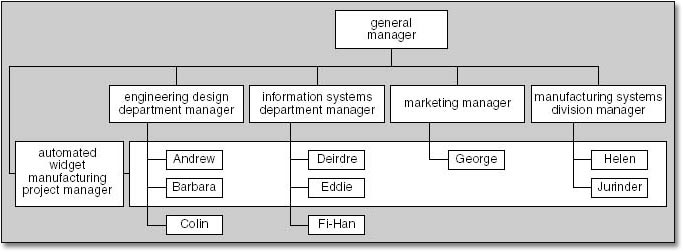

In a matrix team, staff report to different managers for different aspects of their work. Matrix structures are often, but not exclusively, found in projects. Matrix structures are more common in large and multi-national organizations. In this structure, staff are responsible to the project manager for their work on the project while their functional line manager may be responsible for other aspects of their work such as appraisal, training, and career development, and ‘routine’ tasks. This matrix project structure is represented in Figure 3. Notice how the traditional hierarchy is cross-cut by the ‘automated widget manufacturing configuration.’

Figure 3: A matrix project structure

In this form of organization, staff from various functional areas (such as design, software development, manufacturing or marketing) are loaned or seconded to work on a particular project. Such staff may work full or part time on the project. The project manager thus has a recognizable team and is responsible for controlling and monitoring its work on the project.

However, many of the project staff will still have other duties to perform in their normal functional departments. The functional line managers they report to will retain responsibility for this work and for the professional standards of their work on the project, as well as for their training and career development. It is important to overcome the problems staff might have with the dual reporting lines (the ‘two-boss’ problem). This requires building good interpersonal relationships with the team members and regular, effective communication.

The contract team

The contract team is brought in from outside in order to do the project work. Here, the responsibility to deliver the project rests very firmly with the project manager. The client will find such a team harder to control directly. On the other hand, it is the client who will judge the success of the project, so the project manager has to keep an eye constantly on the physical outcomes of the project. A variant of this is the so-called ‘outsourced supply team’, which simply means that the team is physically situated remotely from the project manager, who then encounters the additional problem of ‘managing at a distance’.

Mixed Structures

Teams often have mixed structures:

- Some members may be employed to work full time on the project and be fully responsible to the project manager. Project managers themselves are usually employed full time.

- Others may work part time, and be responsible to the project manager only during their time on the project. For example, internal staff may well work on several projects at the same time. Alternatively, an external consultant working on a given project may also be involved in a wider portfolio of activities.

- Some may be part of a matrix arrangement, whereby their work on the project is overseen by the project manager and they report to their line manager for other matters. Project administrators often function in this way, serving the project for its duration, but having a career path within a wider administrative service.

- Still others may be part of a functional hierarchy, undertaking work on the project under their line manager’s supervision by negotiation with their project manager. For instance, someone who works in an organization’s legal department may provide the project team with access to legal advice when needed.

In relatively small projects the last two arrangements are a very common way of accessing specialist services that will only be needed from time to time.

Activity 4

What are some of the relative benefits and drawbacks to some of these team configurations?

Which one is best for a large and complex problem? Which is normal for a straightforward task?

Modern teams

In addition to the traditional types of teams or groups outlined above, recent years have seen the growth of interest in three other important types of team: ‘self-managed teams’, ‘self-organizing teams’, and ‘dispersed virtual teams.’

A typical self-managed team may be permanent or temporary. It operates in an informal and non-hierarchical manner, and has considerable responsibility for the way it carries out its tasks. It is often found in organizations that are developing total quality management and quality assurance approaches. The Industrial Society Survey observed that: “Better customer service, more motivated staff, and better quality of output are the three top motives for moving to [self-managed teams], managers report.”

In contrast, organizations that deliberately encourage the formation of self-organizing teams are comparatively rare. Teams of this type can be found in highly flexible, innovative organizations that thrive on creativity and informality. These are modern organizations that recognize the importance of learning and adaptability in ensuring their success and continued survival. However, self-organizing teams exist, unrecognized, in many organizations. For instance, in traditional, bureaucratic organizations, people who need to circumvent the red tape may get together in order to make something happen and, in so doing, spontaneously create a self-organizing team. The team will work together, operating outside the formal structures, until its task is done and then it will disband.

Table 2 shows some typical features of self-managed and self-organizing teams.

Table 2: Comparing Self-managed and Self-Organizing Teams

| Self-managed team | Self-organizing team |

| Usually part of the formal reporting structure | Usually outside the formal reporting structure |

| Members usually selected by management | Members usually self-selected volunteers |

| Informal style of working | Informal style of working |

| Indirectly controlled by senior management | Senior management influences only the team’s boundaries |

| Usually a permanent leader, but may change | Leadership variable – perhaps one, perhaps changing, perhaps shared |

| Empowered by senior management | Empowered by the team members and a supportive culture and environment |

Many organizations set up self-managed or empowered teams as an important way of improving performance and they are often used as a way of introducing a continuous improvement approach. These teams tend to meet regularly to discuss and put forward ideas for improved methods of working or customer service in their areas. Some manufacturers have used multi-skilled self-managed teams to improve manufacturing processes, to enhance worker participation and improve morale. Self-managed teams give employees an opportunity to take a more active role in their working lives and to develop new skills and abilities. This may result in reduced staff turnover and less absenteeism.

Self-organizing teams are usually formed spontaneously in response to an issue, idea or challenge. This may be the challenge of creating a radically new product, or solving a tough production problem. In Japan, the encouragement of self-organizing teams has been used as a way of stimulating discussion and debate about strategic issues so that radical and innovative new strategies emerge. By using a self-organizing team approach companies were able to tap into the collective wisdom and energy of interested and motivated employees.

Increasingly, virtual team are also common. A virtual team is one whose primary means of communicating is electronic, with only occasional phone and face-to-face communication, if at all. However, there is no single point at which a team ‘becomes’ a virtual team (Zigurs, 2003). Table 3 contains a summary of benefits virtual groups provide to organizations and individuals, as well as the potential challenges and disadvantages virtual groups present.

Table 3. Teams have organizational and individual benefits, as well as possible challenges and disadvantages

| The Organization Benefits | The Individual Benefits | Possible Challenges and Disadvantages |

| People can be hired with the skills and competences needed regardless of location | People can work from anywhere at any time | Communicating effectively across distances |

| In some cases, working across different time zones can extend the working day | Physical location is not a recruitment issue; relocation is unnecessary | Management lacks the planning necessary for a virtual group |

| It can enable products to be developed more quickly | Travelling expenses and commuting time are cut | Technology is complicated and/or unfamiliar to some or all members |

| Expenses associated with travel and relocation can be cut; Carbon emissions can be reduced. | People can work from anywhere at any time | Difficult to coordinate times and hard to squeeze all the information into a more narrow time slot |

Why do (only some) teams succeed?

Clearly, there are no hard-and-fast rules which lead to team effectiveness. The determinants of a successful team are complex and not equivalent to following a set of prescriptions. However, the results of poor teamwork can be expensive, so it is useful to draw on research, experience and case studies to explore some general guidelines. What do I mean by ‘team effectiveness’? – the achievement of goals alone? Where do the achievements of individual members fit in? and How does team member satisfaction contribute to team effectiveness?

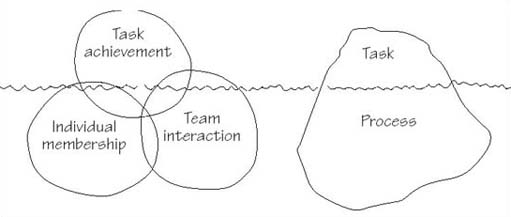

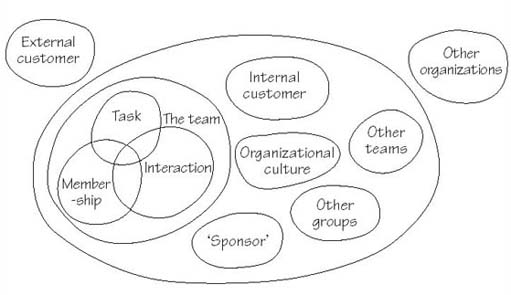

Borrowing from Adair’s 1983 leadership model, the left-hand side of Figure 4 shows the main constituents of team effectiveness: the satisfaction of individual membership needs, successful team interaction and the achievement of team tasks. These elements are not discrete, so Figure 4 shows them as overlapping. For example, team member satisfaction will be derived not only from the achievement of tasks but also from the quality of team relationships and the more social aspects of team working: people who work almost entirely on their own, such as teleworkers and self-employed business owner-managers, often miss the opportunity to bounce ideas off colleagues in team situations. The experience of solitude in their work can, over time, create a sense of isolation, and impair their performance. The effectiveness of a team should also relate to the next step, to what happens after the achievement of team goals.

Figure 4: The internal elements of team effectiveness

The three elements could be reconfigured as an iceberg, most of which is below the water’s surface (the right-hand side of Figure 4). Superficial observation of teams in organizations might suggest that most, if not all, energy is devoted to the explicit task (what is to be achieved, by when, with what budget and what resources). Naturally, this is important. But too often the concealed part of the iceberg (how the team will work together) is neglected. As with real icebergs, shipwrecks can ensue.

For instance, if working in a particular team leaves its members antagonistic towards each other and disenchanted with the organization to the point of looking for new jobs, then it can hardly be regarded as fully effective, even if it achieves its goals. The measure of team effectiveness could be how well the team has prepared its members for the transition to new projects, and whether the members would relish the thought of working with each other again.

In addition to what happens inside a team there are external influences that impact upon team operations. The factors shown in Figure 4 interact with each other in ways that affect the team and its development. We don’t fully understand the complexity of these interactions and combinations. The best that we can do is discuss each factor in turn and consider some of the interactions between them and how they relate to team effectiveness. For instance, discussions about whether the wider culture of an organization supports and rewards teamworking, whether a team’s internal and/or external customers clearly specify their requirements and whether the expectations of a team match those of its sponsor will all either help or hinder a team’s ongoing vitality.

Figure 5: Systems map showing components influencing team effectiveness

Advantages and Disadvantages of Small Groups

As with anything, small groups have their advantages and disadvantages. Advantages of small groups include shared decision making, shared resources, synergy, and exposure to diversity. It is within small groups that most of the decisions that guide our country, introduce local laws, and influence our family interactions are made. In a democratic society, participation in decision making is a key part of citizenship. Groups also help in making decisions involving judgment calls that have ethical implications or the potential to negatively affect people. Individuals making such high-stakes decisions in a vacuum could have negative consequences given the lack of feedback, input, questioning, and proposals for alternatives that would come from group interaction. Group members also help expand our social networks, which provide access to more resources. A local community-theater group may be able to put on a production with a limited budget by drawing on these connections to get set-building supplies, props, costumes, actors, and publicity in ways that an individual could not. The increased knowledge, diverse perspectives, and access to resources that groups possess relates to another advantage of small groups—synergy.

Synergy refers to the potential for gains in performance or heightened quality of interactions when complementary members or member characteristics are added to existing ones (Larson Jr., 2010). Because of synergy, the final group product can be better than what any individual could have produced alone. When I worked in housing and residence life, I helped coordinate a “World Cup Soccer Tournament” for the international students that lived in my residence hall. As a group, we created teams representing different countries around the world, made brackets for people to track progress and predict winners, got sponsors, gathered prizes, and ended up with a very successful event that would not have been possible without the synergy created by our collective group membership. The members of this group were also exposed to international diversity that enriched our experiences, which is also an advantage of group communication.

Participating in groups can also increase our exposure to diversity and broaden our perspectives. Although groups vary in the diversity of their members, we can strategically choose groups that expand our diversity, or we can unintentionally end up in a diverse group. When we participate in small groups, we expand our social networks, which increase the possibility to interact with people who have different cultural identities than ourselves. Since group members work together toward a common goal, shared identification with the task or group can give people with diverse backgrounds a sense of commonality that they might not have otherwise. Even when group members share cultural identities, the diversity of experience and opinion within a group can lead to broadened perspectives as alternative ideas are presented and opinions are challenged and defended. One of my favorite parts of facilitating class discussion is when students with different identities and/or perspectives teach one another things in ways that I could not on my own. This example brings together the potential of synergy and diversity. People who are more introverted or just avoid group communication and voluntarily distance themselves from groups—or are rejected from groups—risk losing opportunities to learn more about others and themselves.

There are also disadvantages to small group interaction. In some cases, one person can be just as or more effective than a group of people. Think about a situation in which a highly specialized skill or knowledge is needed to get something done. In this situation, one very knowledgeable person is probably a better fit for the task than a group of less knowledgeable people. Group interaction also has a tendency to slow down the decision-making process. Individuals connected through a hierarchy or chain of command often work better in situations where decisions must be made under time constraints. When group interaction does occur under time constraints, having one “point person” or leader who coordinates action and gives final approval or disapproval on ideas or suggestions for actions is best.

Group communication also presents interpersonal challenges. A common problem is coordinating and planning group meetings due to busy and conflicting schedules. Some people also have difficulty with the other-centeredness and self-sacrifice that some groups require. The interdependence of group members that we discussed earlier can also create some disadvantages. Group members may take advantage of the anonymity of a group and engage in social loafing, meaning they contribute less to the group than other members or than they would if working alone (Karau & Williams, 1993). Social loafers expect that no one will notice their behaviors or that others will pick up their slack. It is this potential for social loafing that makes many students and professionals dread group work, especially those who have a tendency to cover for other group members to prevent the social loafer from diminishing the group’s productivity or output.

Conclusion

This reading has addressed four questions: what characterizes a group, what characterizes a team, how project teams are organized, and what can make teams ineffective. Groups can be formal or informal depending on the circumstances. Work groups or teams are generally more focused on particular tasks and outcomes, and use processes that aim to achieve a unity of purpose, communication and action. I looked at six major types of team: functional, project, matrix, contract, self-managing, self-organizing, and virtual teams. Each form has strengths and weaknesses that suit particular types of project within particular organizational cultures, and teams often involve a mixture of different forms. Team effectiveness is shaped by internal influences – task achievement, individual membership and team interaction – as well as external influences, such as customers, sponsors, other teams, and organizational culture.

IMPROVING YOUR GROUP EXPERIENCES

If you experience feelings of fear and dread when an instructor says you will need to work in a group, you may experience what is called grouphate (Meyers & Goodboy, 2005). Like many of you, I also had some negative group experiences in college that made me think similarly to a student who posted the following on a teaching blog: “Group work is code for ‘work as a group for a grade less than what you can get if you work alone’” (Weimer, 2008).

But then I took a course called “Small Group and Team Communication” with an amazing teacher who later became one of my most influential mentors. She emphasized the fact that we all needed to increase our knowledge about group communication and group dynamics in order to better our group communication experiences—and she was right. So the first piece of advice to help you start improving your group experiences is to closely study the group communication chapters in this textbook and to apply what you learn to your group interactions. Neither students nor faculty are born knowing how to function as a group, yet students and faculty often think we’re supposed to learn as we go, which increases the likelihood of a negative experience.

A second piece of advice is to meet often with your group (Myers & Goodboy, 2005). Of course, to do this you have to overcome some scheduling and coordination difficulties, but putting other things aside to work as a group helps set up a norm that group work is important and worthwhile. Regular meetings also allow members to interact with each other, which can increase social bonds, build a sense of interdependence that can help diminish social loafing, and establish other important rules and norms that will guide future group interaction. Instead of committing to frequent meetings, many student groups use their first meeting to equally divide up the group’s tasks so they can then go off and work alone (not as a group). While some group work can definitely be done independently, dividing up the work and assigning someone to put it all together doesn’t allow group members to take advantage of one of the most powerful advantages of group work—synergy.

Last, establish group expectations and follow through with them. I recommend that my students come up with a group name and create a contract of group guidelines during their first meeting (both of which I learned from my group communication teacher whom I referenced earlier). The group name helps begin to establish a shared identity, which then contributes to interdependence and improves performance. The contract of group guidelines helps make explicit the group norms that might have otherwise been left implicit. Each group member contributes to the contract and then they all sign it. Groups often make guidelines about how meetings will be run, what to do about lateness and attendance, the type of climate they’d like for discussion, and other relevant expectations. If group members end up falling short of these expectations, the other group members can remind the straying member of the contact and the fact that he or she signed it. If the group encounters further issues, they can use the contract as a basis for evaluating the other group member or for communicating with the instructor.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Do you agree with the student’s quote about group work that was included at the beginning? Why or why not?

- The second recommendation is to meet more with your group. Acknowledging that schedules are difficult to coordinate and that that is not really going to change, what are some strategies that you could use to overcome that challenge in order to get time together as a group?

- What are some guidelines that you think you’d like to include in your contract with a future group?

Review & Reflection Questions

- What are the key characteristics of small groups?

- List some groups to which you have belonged that focused primarily on tasks and then list some that focused primarily on relationships. Compare and contrast your experiences in these groups.

- Synergy is one of the main advantages of small group communication. Explain a time when a group you were in benefited from or failed to achieve synergy. What contributed to your success/failure?

- Do you experience grouphate? If so, why might that be the case? What strategies could you use to have better group experiences in the future?

References

- Adair, J. (1983) Effective Leadership, Gower.

- Ellis, D. G., & Fisher, B. A. (1994). Small group decision Making: Communication and the group process. (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Industrial Society (1995) Managing Best Practice: Self Managed Teams. Publication no. 11, May 1995, London, Industrial Society.

- Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. (5th ed.). Routledge.

- Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 681-706.

- Makin, P., Cooper, C. and Cox, C. (1989) Managing People at Work, The British Psychological Society and Routledge.

- Myers, S. A., & Goodboy, A. K. (2005). A study of grouphate in a course on small group communication. Psychological Reports, 97(2), 381-386.

- Stanton, A. (1992) ‘Learning from experience of collective teamwork’, in Paton R., Cornforth C, and Batsleer, J. (eds) Issues in Voluntary and Non-profit Management, pp. 95–103, Addison-Wesley in association with the Open University.

- Weimer, M. (2008, July 1). Why students hate groups. The Teaching Professor. Retrieved from http://www.teachingprofessor.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/why-students-hate-groups.

Authors and Attribution

The content included in this chapter is adapted from:

- Lindabary, J. R. (Ed.) (2020). Small Group Communication: Forming & Sustaining Teams. Emporia, KS: Emporia State University.

- Piercy, C. W. (2020). Problem Solving in Teams and Groups. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Libraries.

- Two Open University chapters: Working in Groups and Teams and Groups and Teamwork