5 Thinking as a Group

Thinking as a Group

One of the central aspects of being part of a group is collectively acting and/or making decisions. The ability to participate in a communicative process that values multiple voices and perspectives while coming to some level of agreement is aspirational, but not always what happens. We can look at a number of examples of how groups think together about shared issues of concern in order to better understand what is and isn’t helpful when thinking together as part of a group. Charlan Nemeth (2018), in In Defense of Troublemakers: The Power of Dissent in Life and Business, makes an important point about consensus potentially swaying our judgments, even when it is in error. As she puts it:

“The more insidious aspect of consensus is that, whether or not we come to agree with the majority, it shapes the way we think. We start to view the world from the majority perspective. wether we are seeking or interpreting information, using a strategy in problem-solving, or finding solutions, we take the perspective of that majority. We think in narrow ways–the majority’s ways. On balance, we make poorer decisions and think less creatively when we adopt the majority perspective” (p. 2-3).

Nemeth is quick to point out that dissent also influences our thinking, because “When we are exposed to dissent, our thinking does not narrow as it does when we are exposed to consensus. In fact, dissent broadens our thinking” (Nemeth, 2018, p. 2). The importance of dissenting voices, as will be highlighted in the film Twelve Angry Men, can have significant impacts on individuals, groups, and society. The power of even a single dissenting voice can stimulate thinking about information so that a better decision is reached. In the case of the jury in Twelve Angry Men, the art of influence and the ability to recognize the dynamics of a group helps us to value the minority perspective or position, not only to experience such a voice as a hurdle to quickly overcome.

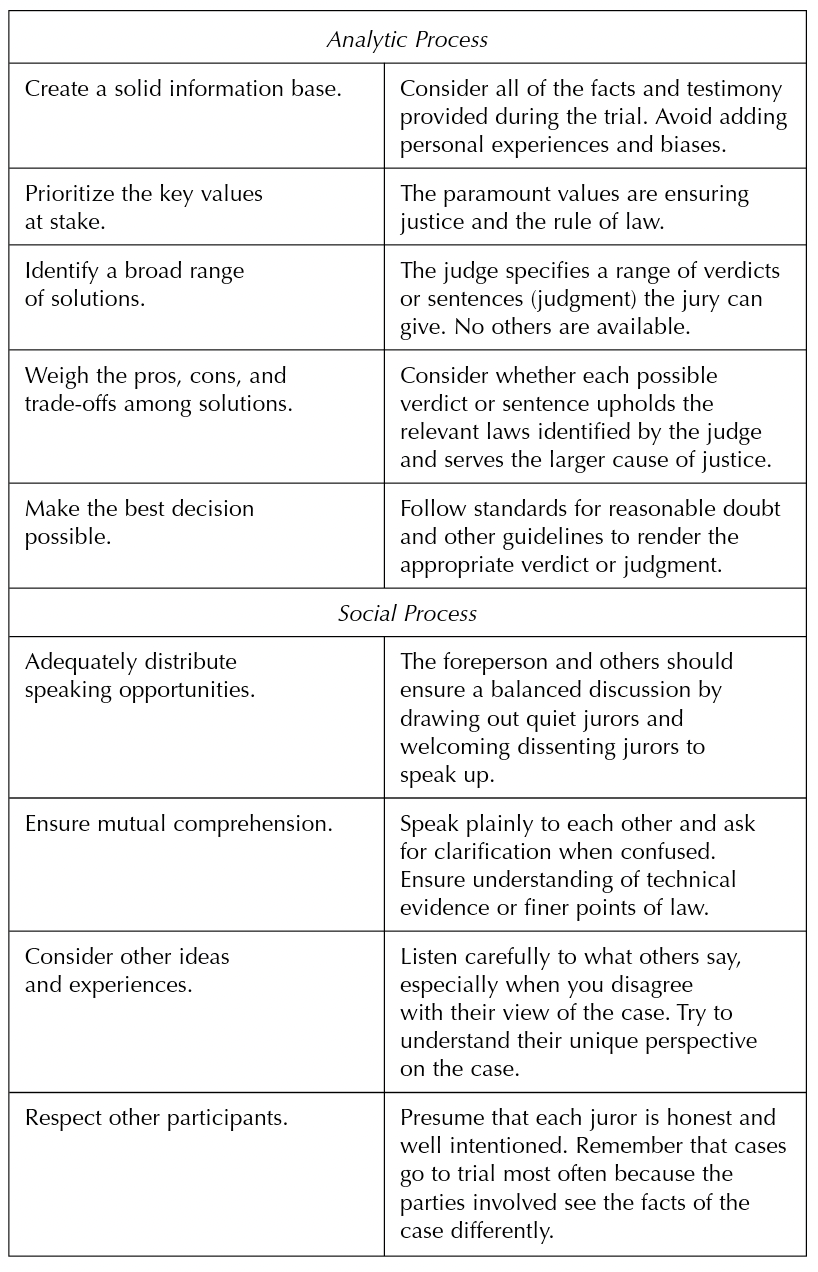

The jury, as Gastil (2010, p. 57) argues, “occupies a special place in American law and the public imagination, and the term deliberation derives much of its current meaning from the jury. As a result, any theory that aims to understand how groups make decisions will need to encompass this most famous of small-group decision-making processes.” In Political Communication and Deliberation, Gastil (2008, p. 157) writes about analytic and social processes that impact how a group makes decisions through a deliberative process.

The analytic and social processes experienced in the jury room, through deliberation, illuminate the different elements of small group communication. When we think about the interplay between deliberative communication with concerns about how a group thinks about a common problem or challenge, we confront the power and influence of majority perspectives. The likelihood of groupthink increases, especially when there are external factors that influence the time and commitment to the issue. Twelve Angry Men highlights a fictional account of how the actions of one member of a jury could alter the process shaped by a desire for consensus. What comes from the experience of a dissenting voice? This fictional film is a powerful example that shapes how we are to think about the power of a singular voice. As Nemeth (2018, p. 12) puts it, “Good decision-making, at its heart, is divergent thinking.” Conversely, bad decision-making is the reverse: “Thinking convergently, we focus more narrowly, usually in one direction” (Nemeth, 2018, p. 12-13).

It is important to stress that agreement is not to be opposed. However, moving too quickly to judgment means that groupthink can shape the decision. When groupthink takes over, we can lose the value of each person’s individual input, the experiences, and opinions one brings to bear on a decision or problem, and any of the creative tension from dissent is diminished. It is because of these concerns that Sam Kaner (2014, p. 19), in Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, offers a helpful concept to think about the challenging work for groups moving from divergent thinking to convergent thinking: the groan zone.

Moving Through the Groan Zone

As Kaner (2014) argues, there is an idealized process for group decision-making. Imagine a sideways diamond and on the far left is the starting point of the awareness of a new topic. It them moves left to right: familiar opinions, diverse perspectives, consolidated thinking, refinements, and finally ending on the far right side of the diamond at a decision point. As Kaner writes, “In theory, a group that has committed itself to thinking through a difficult problem would move forward in orderly, thoughtful steps. First, the group would generate and explore a diverse set of ideas. Next, they would consolidate the best thinking into a proposal. Then, they’d refine the proposal until they arrived at a final decision that nicely incorporated the breadth of their thinking” (2014, p. 13).”

Kaner acknowledges that the ideal rarely occurs. In practice, it is hard for people to shift from expressing their own opinions to understanding the opinions of others. And it’s particularly challenging to do so when a wide diversity of perspectives are in play. As he notes: “In such cases people can get overloaded, disoriented, annoyed, impatient – or all of the above. Some people feel misunderstood and keep repeating themselves. Others push for closure….” (Kaner 2014, p. 14). This is why the idea of “working through” a public issue is so complicated, going beyond simply public opinion to public judgment, a concept that requires a more thoughtful and deliberative engagement with content and others (Yankelovich, 1991).

Working through the groan zone, with a deliberative mindset, is according to Carcasson (2017), is critical because simply giving space for divergent opinion and providing opportunities for voice, access, and free speech ultimately fall short. Multiple viewpoints can be very difficult to handle, but is becomes essential. A process to create space for divergent voices as well as enable them to be in conversation with one another is key to democratic discussion. As Carcasson puts it, “divergent thinking without a good process to handle it often results in frustration, which in turn leads to increased polarization or cynicism—both of which are counterproductive to democratic decision-making” (Carcasson, 2017, p. 7). This is why small groups must ensure they don’t fall victim to moving too quickly to agreement–to groupthink.

The Challenge(r) of Groupthink: A Case

Have you ever thought about speaking up in a meeting and then decided against it because you did not want to appear unsupportive of the group’s efforts? Or led a team in which the team members were reluctant to express their own opinions? If so, you have probably been a victim of “groupthink”.

Groupthink is a phenomenon that occurs when the desire for group consensus overrides people’s common sense desire to present alternatives, critique a position, or express an unpopular opinion. Here, the desire for group cohesion effectively drives out good decision-making and problem solving.

One well-known example of groupthink in action is the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster.

Engineers of the space shuttle knew about the potential of certain parts being a problem in cold weather, specifically “O-rings.” But, as the Rogers Commission exploring what happened noted, it was a failure of communication. As spaceflight historian Amy Shira Teitel (2021) wrote about the Commission’s findings:

“What it found was a stunning lack of communication—almost as if officials had been playing a game of broken telephone, with the result that incomplete and misleading information reached NASA’s top echelons. And among that ill-translated information were concerns about the O-rings. The issue was completely absent from all the flight-readiness documents.”

Not wanting negative press, NASA pushed ahead with the launch anyway. There was miscommunication within the organization as well as concern about public opinion because of the State of the Union address by President Reagan taking place just hours after the scheduled launch. The desire to complete this mission and have the ability to the president to laud the space program on a nationally-televised address led to the unfortunate reality of groupthink costing seven people their lives. The unfortunate thing for those NASA astronauts who died, for NASA, and the United States of American more generally, is that some individuals tried to stop the launch but politics and pressure interfered.

Bob Ebeling was one of five booster rocket engineers at NASA contractor Morton Thiokol who tried to stop the 1986 Challenger launch. As a 2016 NPR article put it, “They worried that cold temperatures overnight — the forecast said 18 degrees — would stiffen the rubber O-ring seals that prevent burning rocket fuel from leaking out of booster joints” (Berkes, 2016). “We all knew if the seals failed, the shuttle would blow up,” said engineer Roger Boisjoly in a 1986 interview with NPR’s Daniel Zwerdling. Engineers with specific knowledge about the shuttle knew what would happen, but groupthink kept their voices sidelined until well after the fateful explosion.

Irving L. Janis coined the term “Groupthink,” and published his research in the 1972 book republished in 1982, Groupthink : psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes. His findings came from research into why a team reaches an excellent decision one time, and a disastrous one the next. What he found was that a lack of conflict or opposing viewpoints led to poor decisions, because alternatives were not fully analyzed, and because groups did not gather enough information to make an informed decision. Janis suggested that Groupthink happens when there is:

- A strong, persuasive group leader.

- A high level of group cohesion.

- Intense pressure from the outside to make a good decision.

In fact, it is now widely recognized that groupthink-like behavior is found in many situations and across many types of groups and team settings. So it’s important to look out for the key symptoms.

Groupthink is best understood a group pressure phenomenon that increases the risk of the group making flawed decisions by leading to reduced mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment. According to Janis (1982), groupthink is characterized by eight symptoms that include:

- Illusion of invulnerability shared by most or all of the group members that creates excessive optimism and encourages them to take extreme risks.

- Collective rationalizations where members downplay negative information or warnings that might cause them to reconsider their assumptions.

- An unquestioned belief in the group’s inherent morality that may incline members to ignore ethical or moral consequences of their actions.

- Stereotyped views of out-groups are seen when groups discount rivals’ abilities to make effective responses.

- Direct pressure on any member who expresses strong arguments against any of the group’s stereotypes, illusions, or commitments.

- Self-censorship when members of the group minimize their own doubts and counterarguments.

- Illusions of unanimity based on self-censorship and direct pressure on the group; the lack of dissent is viewed as unanimity.

- The emergence of self-appointed mindguards where one or more members protect the group from information that runs counter to the group’s assumptions and course of action.

Groups do tend to be more likely to suffer from symptoms of groupthink when they are large and when the group is cohesive because the members like each other (Esser, 1998; Mullen et al., 1994). The assumption is that the more frequently a group displays one or more of the eight symptoms, the worse the quality of their decisions will be. However, if your group is cohesive, it is not necessarily doomed to engage in groupthink.

Recommendations for Avoiding Groupthink

The following are strategies for avoiding groupthink:

Groups Should:

- Discuss the symptoms of groupthink and how to avoid them.

- Assign a rotating devil’s advocate to every meeting.

- Invite experts or qualified colleagues who are not part of the core decision-making group to attend meetings, and get reactions from outsiders on a regular basis and share these with the group.

- Encourage a culture of difference where different ideas are valued.

- Debate the ethical implications of the decisions and potential solutions being considered.

Individuals Should:

- Monitor their own behavior for signs of groupthink and modify behavior if needed.

- Check themselves for self-censorship.

- Carefully avoid mindguard behaviors.

- Avoid putting pressure on other group members to conform.

- Remind members of the ground rules for avoiding groupthink if they get off track.

Group Leaders Should:

- Break the group into two subgroups from time to time.

- Have more than one group work on the same problem if time and resources allow it. This makes sense for highly critical decisions.

- Remain impartial and refrain from stating preferences at the outset of decisions.

- Set a tone of encouraging critical evaluations throughout deliberations.

- Create an anonymous feedback channel where all group members can contribute to if desired.

Tools That Help You Avoid Groupthink

| Group Techniques: | |

|---|---|

| Brainstorming | Helps ideas flow freely without criticism. |

| Modified Borda Count | Allows each group member to contribute individually, so mitigating the risk that stronger and more persuasive group members dominate the decision making process. |

| Six Thinking Hats | Helps the team look at a problem from many different perspectives, allowing people to play “Devil’s Advocate”. |

| The Delphi Technique | Allows team members to contribute individually, with no knowledge of a group view, and with little penalty for disagreement. |

| Decision Support Tools: | |

| Risk Analysis | Helps team members explore and manage risk. |

| Impact Analysis | Ensures that the consequences of a decision are thoroughly explored. |

| The Ladder of Inference |

Helps people check and validate the individual steps of a decision-making process. |

Key Points

Groupthink can severely undermine the value of a group’s work and, at its worst, it can cost people their lives.

On a lesser scale, it can stifle teamwork, and leave all but the most vocal team members disillusioned and dissatisfied. If you’re on a team that makes a decision you don’t really support but you feel you can’t say or do anything about it, your enthusiasm will quickly fade.

Teams are capable of being much more effective than individuals but, when groupthink sets in, the opposite can be true. By creating a healthy group-working environment, you can help ensure that the group makes good decisions, and manages any associated risks appropriately.

Group techniques such as Brainstorming, the Modified Borda Count, and Six Thinking Hats can help with this, as can other decision making and thinking tools.

References

- Berkes, H. (2016). “Challenger Engineer Who Warned Of Shuttle Disaster Dies.” NPR. 21 Mar. 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/03/21/470870426/challenger-engineer-who-warned-of-shuttle-disaster-dies

- Esser, J. K. (1998). Alive and well after 25 years: A review of groupthink research. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73, 116–141.

- Gastil, J. (2010). The Group in Society. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Gastil, J. W. (2008). Political Communication and Deliberation. Thousand Oaks: Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Janis, I. L. (1982). Groupthink : psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes (2nd , rev. ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Kaner, S. (2014). Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making (Third ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Mullen, B., Anthony, T., Salas, E., & Driskell, J. E. (1994). Group cohesiveness and quality of decision making: An integration of tests of the groupthink hypothesis. Small Group Research, 25, 189–204.

- Nemeth, C. (2018). In Defense of Troublemakers: The Power of Dissent in Life and Business. New York: Basic Books.

- Teitel, A. S. (2021). “Challenger Explosion: How Groupthink and Other Causes Led to the Tragedy.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 25 Jan. 2018, updated 16 Apr. 2021. www.history.com/news/how-the-challenger-disaster-changed-nasa.

Authors & Attribution

Sections of this chapter draw from Lindabary, J. R. (Ed.) (2020). Small Group Communication: Forming & Sustaining Teams. Emporia, KS: Emporia State University.