4 Principles and Practice of Plain Language Protocols: Helping Human Readers Find, Understand, and Use Important Information (Ackerman)

Plain Language is the “writing and setting out of essential information in a way that gives a cooperative, motivated persona a good chance of understanding it at first reading, and in the same sense that the writer meant it to be understood.” (Willerton, 2015)

Student Learning Objectives

- Students will consider the differences between traditional academic writing and technical writing in the context of contemporary online communication.

- Students will learn how to analyze grade-level readability.

- Students will acquire knowledge of the history and practice of Plain Language Principles in United States government and military operations.

- Students will learn how the Principles of Plain Language can help writers craft more efficient documents designed to help readers Find, Understand, and Use critical information more effectively.

The global communities in which people live and work are constantly changing. Technology influences how people access and interpret information, adapt to changing situations, make complex decisions, solve critical problems, and evaluate actions.

Online environments demand that writers explore new ways to communicate. Rhetorical purpose continues to influence modes and methods of communication. But in a technology-driven world filled with endless stores of unfiltered content, readers will gravitate towards transparent and efficient documents that help them Find, Understand, and Use information in the most efficient manner possible. Plain Language protocols enhance the readability of online papers, especially those intended for audiences with diverse reading abilities.

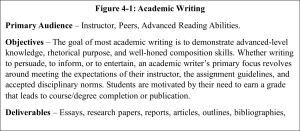

Academic Writing

Throughout primary and secondary education, students are taught to prepare for college by honing their academic writing skills (including grammar, sentence fluency, organization, and vocabulary). While rhetorical principles related to ethos, pathos, and logos enhance critical thinking abilities, academic writing typically occurs within the following framework:

Discussion Questions

A. Consider your pre-college educational experiences in writing instruction:

- What do you remember about the instruction you received in writing?

- What types of writing assignments were you asked to complete?

- Did you consider yourself to be a good writer? Did you like to write?

- How important was your early writing instruction to your academic success

B. Now, think about your college, military, or post-high-school writing experiences:

- What types of training have you received in writing since high school?

- What kinds of documents did you write in college? Who read them?

- What types of documents do you write for work now? Who reads them?

- What types of documents do you read for work now? For your daily life?

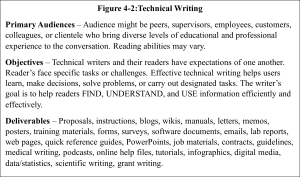

Technical Writing

Advances in technology impact the habits and critical thinking abilities of a diverse readership. Access to unlimited sources of information and facts requires readers to search, sort, and filter endless amounts of content. Writing and publishing in online platforms redefine most authors as technical writers, regardless of educational background or professional discipline. If readers are being asked to act based on your writing, the effectiveness of your message depends on your ability to craft efficient, readable, and visually appealing documents.

Relationships between technical writers and their readers are more interactive, as both parties bring expectations to the table. You may need your readers to learn something, complete an important task, or make critical decisions. Readers need precise information to enhance understanding, complete tasks, or solve particular problems. As the volume of available information continues to grow, the need for more readable texts increases.

To meet their intended goals, technical writers must practice precise and efficient methods of communication that enable diverse audiences to find, understand, and use vital information efficiently and effectively.

“Technical communication encompasses a set of activities that people do to discover, shape, and transmit information.” (Markel 2019)

Readability Analysis

- What Does it Mean for a Document to be Readable?

- Who decides whether a textbook is appropriate for a 4th-grade or 11th-grade reading level?

- What reading grade level do mainstream journalists target to reach the general public?

- Who determines whether a student’s essay is “college-level? Are grades subjective?

What makes a document “readable?” Why does it matter?

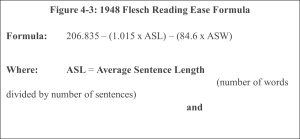

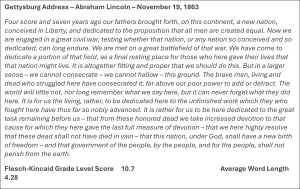

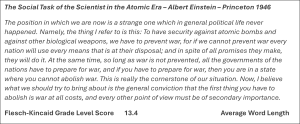

During World War II, U.S. military officials expressed concern that documents being published for use by enlisted soldiers were being written above their abilities to read and understand. In their quest to publish more readable documents, they consulted Rudolph Flesch about ways to ensure the government documents were more accessible for the average public citizen to read.

Fleisch-Kincaid Readability Analysis Formulas

Rudolph Flesch

Rudolf Flesch (May 1911- Oct. 1986) was an Austrian-born naturalized American author, writing consultant, and supporter of the Plain English Movement. He advocated a return to phonics and proposed the Reading Ease Readability Formula. (Flesch, 1948)

Flesch’s 1948 readability formula rates a block of text on a 100-point scale; the higher the score, the easier it is for readers to understand the document. Most standard documents written to be read and understood by the general public should aim for a Flesch score of approximately 60-70.

Flesch Reading Ease Score Interpretation:

90-100 Easily understandable by an average 11-year-old reader

60-70 Easily understandable by an average 13–15-year-old reader.

0-30 Best understood by college graduates.

Examples of publications analyzed using the Flesch Reading Ease Score:

Reader’s Digest Magazine 65 (13–15-year-old readers)

Time Magazine 52 (College Graduates)

Average Grade 7 Student 60-70 (13–15-year-old readers)

Harvard Law Review 30 (College Graduates)

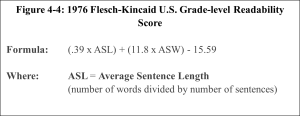

U.S. Grade-level Readability Score

U.S. government agencies wanted a method of analyzing the readability of a document based on a grade-level scoring system.

John P. Kincaid (et al.)

In 1976, under contract with the U.S. Navy, John P. Kincaid modified Flesch’s Reading Ease Formula, producing the Flesch-Kincaid U.S. Grade-level Readability Score. Assisting the Navy in producing more readable documents to be used by enlisted sailors. (Kincaid, 1976)

The Flesh-Kincaid Grade Level Readability Score rates text on a U.S. school grade level. For example, a score of 8.0 means that an 8th-grade student should be able to read and understand a particular piece of text. Pedagogical studies recommend that documents written for use by the U.S. general public aim for a Flesh-Kinkaid Grade Level score of approximately 7.0-8.0.

This formula became a valuable tool for textbook selection committees in public education.

Before advanced computer technology, textbook review committees were required to manually apply Kincaid’s formula to blocks of text to assess appropriate grade levels for individual textbooks. Over 40 different readability formulas were later developed.

Technological Advancements

Time and technology continue to advance the ways in which readability analysis tools are used. Educators serving on textbook selection committees are no longer required to manually apply readability formulas to determine appropriate grade-level readability for textbooks. Computers enable educators and publishers to assess appropriate reading levels automatically.

Readability analysis formulas operate within most word-processing software programs, including Google Docs, KWord, Lotus, Microsoft Office, WordPerfect, and WordPro. They use Flesch-Kincaid Readability Analysis in their Tools menus. Text editing software like Writer’s Workbench and Grammarly can quickly assess readability scores. Journalists and young adult literature novelists use readability analysis tools to ensure their content is accessible to their target readership. Florida was the first state to require life insurance policies to maintain a Flesch Reading Ease Score of 45 or above.

Plain language is the writing and setting out of essential information in a way that gives a cooperative, motivated person a good chance of understanding it at first reading, and in the same sense, the writer meant it to be understood. (Cutts, 2009)

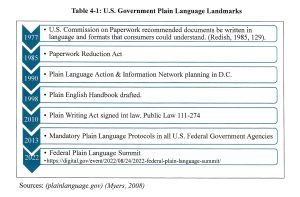

History of U.S. Government Implementation of Plain Language Protocols

Plain language makes reading, understanding, and using government communications more accessible to the public. (plainlanguage.gov)

Sources: (plainlanguage.gov) (Myers, 2008)

U.S. Government Plain Language Guidelines & Resources

Government writing presents a special challenge. Government documents often contain technical information and go out to multiple audiences – some highly knowledgeable, some less so. Government documents have traditionally contained gobbledygook – jargon and complicated, legalistic language. These uninviting letters and reports sound like they are addressed to technical experts and lawyers rather than to readers who need to be influenced or informed. (Myers, 2008)

https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-111publ274

Public Law 111-274 Plain Writing Act signed October 13, 2010

An act to enhance citizen access to Government information and services by establishing that Government documents issued to the public must be written clearly and for other purposes.

http://www.centerforplainlanguage.org

http://execsec.od.nih.gov/plainlang/index.htm

https://www.plainlanguage.gov/

The Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN) is a community of federal employees dedicated to the idea that citizens deserve clear communication from the government. We believe that using plain language saves federal agencies time and money and provides better service to the American public.

Federal Aviation Administration

Federal Aviation Administration Plain Language Guidelines https://www.faa.gov/about/initiatives/plain_language

FAA Plain Language Toolkit

https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/about/initiatives/plain_language/articles/toolkit.pdf

FAA Plain Language Order (FAA 2003 Writing Standards)

The Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) mission is critical to our nation’s safety and economy. We accomplish this mission in partnership with all aviation industry members, as well as our customers and the flying public. That is why we must communicate clearly, effectively, and in plain language that is readily understood by all. Over the years, some of our writing has become dense and needlessly complex. Clarity of communication is a safety issue, and we must strive to communicate clearly and powerfully. I understand this will be an evolutionary process. Let us all begin to work together to make straightforward communication standard practice at FAA. Marion C. Blakey, Administrator, March 31, 2003.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

https://www.opennasa.org/the-plain-language-act.html

The Plain Language Act directs agencies to write in clear, understandable language. At NASA, we have many types of correspondence, ranging from scientific summaries to press releases to rules and directives. As you can imagine, technical terms can be hard to understand. Our goal is to do our best to follow the intent of the Plain Language Act and make our communications easier to read and understand. Like other Federal agencies, we are used to certain styles of writing and find it hard to “break that mold.” However, we pledge to do our best to write in a common-sense style, making it easier for you to understand what we are trying to say. We have many fascinating missions going across the agency, and we hope that our new emphasis on plain language writing will help keep you interested and informed. (Larry Box Dec. December 51)

United States Department of Defense

U.S. Department of Defense Plain Language Guidelines

https://www.esd.whs.mil/dd/plainlanguage/

DoD Plain Language Instruction Program

https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/502513p.pdf?ver=2018-05-31-081817-327

This issuance applies to OSD, the Military Departments, the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Joint Staff, the Combatant Commands, the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Defense, the Defense Agencies, the DoD Field Activities, and all other organizational entities within the DoD (referred to collectively in this issuance as the “DoD Components”).

(1) Implements a plain language program.

(2) DoD personnel are required to use plain language concepts in their documents and on their websites. Documents and websites requiring technical or specialized language should be as clear and concise as possible.

(3) Maintains the DoD Plain Language Website (referred to in this issuance as “the Website”) at https://www.esd.whs.mil/DD/plainlanguage as the official DoD source for Plain Writing Act requirements, training, and compliance information.

National Archives and Records Administration

https://www.archives.gov/open/plain-writing/10-principles.html

Top 10 Principles for Plain Language

Plain language is clear, concise, organized, and appropriate for the intended audience.

- Write for your reader, not yourself. Use pronouns when you can.

- State your central point(s) first before going into details.

- Stick to your topic. Limit each paragraph to one idea and keep it short.

- Write in an active voice. Use the passive voice only in rare cases.

- Use short sentences as much as possible.

- Use everyday words. If you must use technical terms, explain them in the first reference.

- Omit unneeded words.

- Keep the subject and verb close together.

- Use headings, lists, and tables to make reading easier.

- Proofread your work and have a colleague proof it as well.

Federal Aviation Administration

Plain Language Tool Kit

/https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/about/initiatives/plain_language/articles/toolkit.pdf

Before You Write, Your Reader Says

Know your audience and your purpose. Please tell me what I need to know.

Write to each audience separately. Please write to me, not to a group.

Write for your reader, not for everyone. Anticipate my questions.

Think clearly, then write plainly. Please don’t confuse me.

Your Goals Your Values

Find what they need. Challenge every word.

Understand what they find the FIRST time. Simple and less are better.

Use what they find. Make it readable and understandable.

Chunking of Information Don’t dumb “down:” transparent “up.”

Format Tools Word Tools

Short Sentences – Average 15-20 words Everyday Words – Conversational

Headings – question, topic, or statement. Use Pronouns – Speak to the reader.

Tables – Columns and rows of information Active Voice – Verb after subject

Relevant Illustrations – Worth a thousand words Active Verbs – Not passive “to be.”

Short Paragraphs – Less than seven lines Present Tense – Not past or future

Layout – Visual Rhetoric Contractions – Use them.

Vertical lists – Number or bullet points Acronyms – #1 Reader complaint

Blank Space – As important as words Less Jargon, Modifiers, Doublets

NO “shall” – use must, may, should

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/TechMemoGuidelines.pdf

The National Weather Service (NWS) will be implementing changes to its hazard messaging headlines no earlier than the calendar year 2025. It will be collecting public comments on changes to display options through June June 163. The NWS “Advisory” and “Special Weather Statements” headlines will replace plain language headlines. This new plain language product will be in a bulleted “What, Where, When, Impacts” format and equipped with a computer-readable Valid Time Event Code (VTEC). Transitioning to plain language necessitates changes to the national map of active alerts and the local forecast pages. As such, the NWS is currently exploring options for these displays, including proposed color and wording adjustments.

The government setting presents some unique challenges to writers because of both the audience and the type of information government entities typically convey. Federal employees are beginning to understand that the plain language initiative isn’t simply the federal government’s newest writing fad. It saves dollars, keeps writers out of court, makes readers happier, and makes our jobs easier. The cry for more precise writing has been around for a long time. In today’s world of information overload, that cry is being heeded. (Myer, 2008).

Plain Language Action and Information Network

On September 93, Katherine Spivey, Co-Chair of the Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN), presented a webinar on plain writing principles and how to apply them to Web writing. She also addressed how federal writers can comply with the Plain Writing Act of 2010.

When you send out something, would you be happy to receive it? Would you know what you are supposed to do with it? Would you sit there and ask yourself, ‘Why did I get this?’ What am I supposed to do with this? This is the golden rule of Plain Language. Spivey, 2023.

You can watch Katherine Spivey’s webinar in the following video link:

Implications For Future Online Communication

Government systems are slow to change. In 2014, after decades of research, discourse, and policymaking, all U.S. Federal Government Agencies implemented Plain Language. Hopefully, this initiative has resulted in increased levels of consumer satisfaction, comprehension, and compliance. If the public can find, understand, and use essential information quickly, both time and money can be saved for consumers and agencies. It makes sense that these same standards may one day require states and agencies to apply for federal funding through grants and programs. Successful business and industry partners increasingly rely on trained technical writers to maintain functional online communication systems.

While academic writing maintains important roles for education and humanity, technological advancements make tools like Plain Language increasingly more relevant.

“Easy reading is damned hard writing.” Nathaniel Hawthorne

Assignments

- Select one of the agencies listed in this chapter. Use the linAgency’sAgency’ssit thaAgency’s Plain Language Protocols. Review the policies. Then, visit the web page of an agency or company you have worked for. What changes would make your organization’s webpage comply with Plain Language Protocols? How could your web page become more readable?

- Write a 3-minute elevator speech that explains Plain Language to your boss.

- Analyze a piece of your writing for “grade-level readability” by opening it in Microsoft Word. Click on the Review tab. Select Editor. In the Editor pane, scroll to Insights. Select Document stats for your Flesch-Kincaid Grade-level Readability Score.

What grade level does your document read at? Did your score surprise you?

- Spend some time revising your document using Plain Language protocols (e.g., active verbs, personal pronouns, shorter sentences, direct plain language, bulleted lists). Now, run your new text through the Flesch- Kincaid Analysis. What happened to your score?

References

Corsino, Bruce. Plain Language Tool Kit. FAA Plain Language Program Office. /https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/about/initiatives/plain_language/articles/toolkit.pdf

Cutts, Martin. 2009. Oxford Guide to Plain English. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

DeVoss, Danielle Nicole, Eidman, E., and Hicks, T. Because Digital Writing Matters: Improving Student Writing in Online and Multimedia Environments. Jossey-Bass. 2010.

Dorney, Jaqueline M. 1988. The Plain English Movement. English Journal 77 (3):49-51.

Einstein, Albert. The Social Task of the Scientist in the Atomic Era. Princeton. 1946.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. Chance for Peace Speech. April 1, April 16, Eisenhower Presidential Library 2024.

Farr, J.N., Jenkins, J.J., and Paterson D.G. Simplification of Flesch Reading Ease Formula. Journal of Applied Psychology 35.5 (October 1951):333-337.

Federal Aviation Administration. Plain Language. Accessed May 1, May 1 https://www.faa.gov/about/initiatives/plain_language/

Flesch, Rudolf. A New Readability Yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology 32 (1948): 221-233.

Flesch, Rudolf. Why Johnny Can’t Read – And What You Can Do About It. 1955. Harper and Brothers. New York, NY.

“Flesch-Kincaid Readability Tests.” Wikipedia. 2009. 4 Apr April 4http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flesch-Kincaid_Readability_Test.

Kincaid, J.P., R.P. Fishburne, R.L. Rogers, and B.S. Chissom. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count, and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. Research Branch Report 8-75. 1976.

Lincoln, Abraham. Gettysburg Address. November November 19

Markel, Mike, and Stuart A. Selber. Practical Strategies for Technical Communication: A Brief Guide. 3rd Edition. Bedford/St. Martin’s. Boston/New York. 2019.

Myers, Judith Gillespie. Plain Language in Government Writing: A step-by-step guide. Management Concepts, Inc. Vienna, Virginia. 2008.

Readability Scores. Microsoft Office Online. 2009. 4 Apr April 4http://office.microsoft.com/assistance/hfws.aspx.

Redish, Janice C. 1985. The Plain English Movement. The English Language Today, edited by Sidney Greenbaum, 125-38. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Rose, Mike. The Mind at Work: Valuing the Intelligence of the American Worker. 10th Edition. July 26 July 26 Penguin Random House Books. www.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Spivey, Katherine. Wall of Words. Plain Language Writing for the Web. Plain Language Action and Information Network. September 2023. https://youtu.be/BB7oznnz3lQ.

Willerton, Russell. Plain Language and Ethical Action: A Dialogic Approach to Technical Content in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. New York, New York. 2015.