5 The Informative Report

Informative Report Assignment Description

What Will You Do?

This unit synthesizes and extends the research, analysis, and writing skills that you have been practicing throughout the semester. You will investigate a social problem, issue, or phenomenon related to race and ethnicity in the United States. Your purpose will be to inform a reader – a public official – who will find your research significant, interesting, and satisfying. By researching the causes and consequences of this issue, you allow your reader to understand the historical and institutional reasons for why this problem persists and better appreciate the consequences of the problem.

Your Informative Report will be 1500-2400 words and will be delivered, as many formal reports are, in extended memo format. You will need to address a public official, who should also have something at stake in the social problem that you are investigating. You must incorporate at least five credible sources that you find through independent research.

The purpose of an informative report is to synthesize information from several sources and present it in an informative and readable fashion. This type of writing is common in diverse settings, including businesses, non-profits, and governmental organizations. For example, Congress has an entire department, the Congressional Research Service (CRS), that it directs to gather knowledge prior to informational and policy-related hearings as well as when requested by individual representatives and senators.

Here is the first of many research tips in this unit: CRS reports are public information available to you through the library and are an excellent source of information for your own report. In rough terms, you will be doing exactly what the CRS does when directed to research a topic. You will assemble the best available sources and information. You will objectively summarize those sources and that information. Then you will synthesize your research and summaries into a single report containing what you have learned. As we work on developing strong research practices, we will discuss how to choose the best sources and how to provide the best, most reliable evidence to your audience.

Who Will Read Your Report?

At the heart of informative writing is the issue of audience: who needs to know the information you have found and why do they need to know it? For this assignment, you will be writing to a public official of your choice. You could write to officials at this university, local officials, state officials, or officials back in your hometown. You could write your congressperson, your senator, or the President of the United States. Each of these audiences requires different information, however.

For example, if you are writing to the President of Kansas State University, you might provide a synthesis of information on how race structures access to education. However, you have to think about what information is most useful to this particular reader. While national data might provide some insight, racial demographics vary between states, so you might look instead for more specific data to the state of Kansas. In general, you should always seek to tailor your information most specifically to the population you are addressing (i.e. state data for state officials, national data for federal officials). Additionally, you will want to consider what your target audience likely already knows and tailor your information to provide the most important and relevant information for that audience. You will also need to be attentive to how current your information is, making sure that you are providing the best information to support your reader’s action. For example, while education segregation levels in Kansas in 1967 may be important information, it may not be especially relevant to the current President of Kansas State University in considering the role of race in present day college admissions in Kansas.

The reason we are writing to public officials is that, as your research in the causes of these racial and ethnic problems will show, these conversations about race and ethnicity in the United States are not accidental nor do they reflect actual or real differences between people of different races. Instead, the realities that we live in are the product of history and public policy. Because of this, the social problems and disparities that we research must necessarily be addressed, at least to a substantial degree, through public policy as well. Consider your research as the first step in attempting to solve these persistent social problems.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this assignment, you should be able to do the following:

- Inform an audience about the causes and consequences of an issue or a problem related to race and ethnicity

- Narrow the scope of an issue to one that is manageable and researchable

- Identify an audience for whom the topic is relevant and significant, and be able to explain why this audience is interested in your findings

- Research the causes and consequences of the issue using appropriate and relevant sources

- Evaluate the appropriateness and credibility of your research sources

- Develop, synthesize, and demonstrate your understanding of source material accurately and usefully for your audience

- Develop your analysis of the source material directly to your audience’s needs

- Integrate outside sources usefully for your audience

- Follow appropriate report format

- Apply the basic principles of MLA formatting and in-text citation (or another citation system of your choice) and construct a properly formatted MLA Works Cited page (or another citation system)

Rationale

This assignment relates directly to several of the Undergraduate Student Learning Outcomes at K-State, including knowledge, diversity, communication, and academic and professional integrity. Most importantly, this writing task asks you to pay attention to your readers and to figure out how your topic is significant to them. In English 200, as well as other classes that demand academic writing, you will be expected to write for different audiences, evaluate the credibility and suitability of research sources, and find effective ways to organize and integrate these sources. Moreover, researching the causes and consequences of a problem is an important part of what researchers do in the social sciences, business, and other academic and professional disciplines. For example, in Leadership Studies, researchers are asked to investigate problems – in terms of both causes and effects – in order to help inform the solutions they may adapt.

Additionally, as an adult who may be thrust into conversations about race and ethnicity at your university or other communities, you need to be familiar with these debates about racial and ethnic differences and disparities, and you need to be aware of such concepts as “structural” or “institutional” racism. You are not expected to become a sociologist, critical race theorist, or social historian, yet you are expected to demonstrate your curiosity, flexibility, and open- mindedness as you investigate the causes and consequences of important social issues and problems. These are challenges that you will experience as a university student, a member of the public, and an employee or intern in a company or organization. Moreover, you will find that such “soft skills” as flexibility and open-mindedness will be demanded by future workplaces.

Writing about Race and Ethnicity

In the Visual Analysis unit, you learned about the distinction between biological sex and gender: as opposed to the biological reality of differences in sex (although these differences do not conform to a strict male/female binary), gender is a socially constructed category. Or, to quote Simone de Beauvoir, “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Race, like gender, is a socially constructed category. Unlike gender, however, there is no equivalent of biological sex for race. While American society associates specific physical traits with different races (e.g., dark skin), our readings and your research in this unit will illustrate just how deceptive those associations can be. As biologists have shown, there is as much genetic diversity within any individual race as there is between races. Below, you see a postage stamp commemorating Charles Chesnutt, a major African American author from the turn of the twentieth century. As you may have noticed, Chesnutt’s skin is not dark at all. Were it not for the caption reading “Black Heritage,” it is entirely possible that many of you might have identified Chesnutt as white. While this single postage stamp only proves that there are many different skin colors within the racial category of “black,” this example also indicates just how fluid our categories can be.

Furthermore, those categories change over time, and even within individual lives. For example, the scholar Noel Ignatiev’s book How the Irish Became White traces how individuals of Irish descent were first viewed as a separate and inferior race before being accepted as part of a larger race categorized as “white.” Recent research by sociologists Aliya Saperstein and Andrew Penner uses the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth—which has followed about 12,000 Americans throughout their lives since the late 1970s—to show that how an individual is identified by race can shift within that individual’s lifetime. Because researchers in the Survey make note of the race of their interviewees, Saperstein and Penner noticed that some individuals were identified as members of different races at different times based on specific life events that occurred. For example, Saperstein and Penner noted that survey respondents were more likely to have their race labeled as black following the loss of a job or a stay in prison, even if, in previous surveys, they had been labeled as white. Saperstein and Penner concluded that stereotypes about the experiences and lives of people of different races change how we identify the races of other people (for Saperstein’s article on their findings, see pg. 232).

Consequently, as you approach conducting research about a problem that is related to race and ethnicity, you first need to think more deeply about what is meant by race. Throughout your life, you are often asked to fill out forms in which you identify yourself by race. Think back to how you filled out those forms. How did you know which racial box to check? How did you know whether you should identify as “white” or “black or African American” or “American Indian or Alaska Native” or “Asian” or “Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander” or “two or more races”? How would your conception of your own race have changed if you had had to choose between the categories on the 1890 census, where you were instructed to write “White,” “Black,” “Mulatto,” “Quadroon,” “Octoroon,” “Chinese,” “Japanese,” or “Indian”?

As even just the changing labels on the United States Census show, definitions of the concept of race change, as do understandings of who is a member of which race. Consequently, our working definition of race has to address that fluidity and incorporate it. To do this, we need to move from language that discusses race as a way of “being” to what such scholars Paula Moya and Hazel Markus call “doing race.” In other words, race is not something that you are, but rather something that you do and that is done to you.

Discussing Quotations Related to Race and Ethnicity

In this section, you will find quotations from prominent researchers who are attempting to move us away from thinking about race and ethnicity as “containers” that group together people’s physical, mental, and other characteristics to, instead, viewing race and ethnicity as concepts that show the active relationships among groups who may possess different levels of social power. As you begin to work on your informative reports, you will want to explore these social contexts – such as the US government and institutions like the education system – and the ways in which they act upon people and influence the ways they perform their racial identities and think about race and ethnicity.

As you read through the following quotations, use these stock questions to guide your notetaking:

- What is the overall takeaway that the researchers are emphasizing about race and ethnicity?

- How do these researchers’ main points differ from “commonsensical” or “traditional” ideas about race and ethnicity?

- How do these researchers’ points challenge your own thinking about race and ethnicity?

- How can you relate these researchers’ points to your own lives, experiences, and reading?

- How can you use these researchers’ takeaways when you are building your own informative report?

Consequently, we need to think about how our individual racial “doing” exists within society. For instance, when you fill out the census form, you are making a racial self-identification; there is no one standing over you forcing you to choose a certain category in response to the question. However, that racial identification is only one part of a larger process, just as the census is only one place in which we identify ourselves racially or are identified racially by others.

Quotations from Paula M. L. Moya and Hazel Rose Markus, “Doing Race: An Introduction”[1]

- Contrary to what most people believe, race and ethnicity are not things that people have or are. Rather, they are actions that people do. Race and ethnicity are social, historical, and philosophical processes that people have done for hundreds of years and are still doing. They emerge through the social transformations that take place among different kinds of people, in a variety of institutional structures (e.g., schools, workplaces, government offices, courts, media), over time, across space, and in all kinds of situations. (4)

- Race is a doing—a dynamic set of historically derived and institutionalized ideas and practices that

- sorts people into ethnic groups according to perceived physical and behavioral human characteristics that are often imagined to be negative, innate, and shared.

- associates differential value, power, and privilege with these characteristics; establishes a hierarchy among the different groups; and confers opportunity accordingly.

- emerges when groups are perceived to pose a threat (political, economic, or cultural) to each other’s worldview or way of life; and/or to justify the denigration and exploitation (past, current, or future) of other groups while exalting one’s own group to claim an innate privilege. (21)

- Ethnicity is a doing—a dynamic set of historically derived and institutionalized ideas and practices that

- allows people to identify, or be identified, with groupings of people on the basis of presumed, and usually claimed, commonalities, including several of the following: language, history, nation or region of origin, customs, religion, names, physical appearance and/or ancestry group.

- when claimed, confers a sense of belonging, pride and motivation.

- can be a source of collective and individual identity. (22)

- In the course of our everyday social interactions, people in the United States collectively perpetuate sets of ideas and practices about what it means to be white, Latina/o, black, Asian American, or American Indian. Sometimes people actively and intentionally devalue and treat people associated with groups other than their own as if they are lesser or unequal. Very often, however, people do race unknowingly and unintentionally just by participating in a world that comes prearranged according to certain racial categories (Adams et al. 2008a). We can see the consequences of the fact that people have done (and continue to do) race everywhere we look. We can observe, for example, that even in states where there are substantial Latina/o or Asian populations, there are very few Latina/o or Asian newscasters and pundits. We can see the effects of race when committees in charge of awarding construction contracts, educational fellowships, prizes for essays or art works, or engineering competitions are entirely made up of white people or have only one committee member who is associated with a minority racial group. These are institutionalized patterns that reflect and perpetuate the inequality resulting from centuries of doing race. (25-26)

Quotations from Howard Winant and Michael Omi’s Racial Formation in the United States.[2]

- There is a continuous temptation to think of race as an essence, as something fixed, concrete, and objective. And there is also an opposite temptation: to imagine race as a mere illusion, a purely ideological construct which some ideal non-racist social order would eliminate. It is necessary to challenge both these positions, to disrupt and reframe the rigid and bipolar manner in which they are posed and debated, and to transcend the presumably irreconcilable relationship between them.

The effort must be made to understand race as an unstable and “decentered” complex of social meanings constantly being transformed by political struggle. With this in mind, let us propose a definition: race is a concept which signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interests by referring to different types of human bodies. Although the concept of race invokes biologically based human characteristics (so-called “phenotypes”), selection of these particular human features for purposes of racial signification is always and necessarily a social and historical process. In contrast to the other major distinction of this type, that of gender, there is no biological basis for distinguishing among human groups along the lines of race. Indeed, the categories employed to differentiate among human groups along racial lines reveal themselves, upon serious examination, to be at best imprecise, and at worst completely arbitrary. (54-55)

- We define racial formation as the sociohistorical process by which racial categories are created, inhabited, transformed, and destroyed. Our attempt to elaborate a theory of racial formation will proceed in two steps. First, we argue that racial formation is a process of historically situated projects in which human bodies and social structures are represented and organized. Next we link racial formation to the evolution of hegemony, the way in which society is organized and ruled. Such an approach, we believe, can facilitate understanding of a whole range of contemporary controversies and dilemmas involving race, including the nature of racism the relationship of race to other forms of differences, inequalities, and oppression such as sexism and nationalism, and the dilemmas of racial identity today. (55)

Quotations from Brown et al.’s “The Origins of Durable Racial Inequality.”[3]

- Discussions of racial inequality commonly dwell on only one side of the color line. We talk about black poverty, black unemployment, black crime, and public policies for blacks. We rarely, however, talk about the gains whites receive from the troubles experienced by blacks. Only when the diverging fates of black and white Americans are considered together—within the same analytic framework—will it be possible to move beyond the current stale debate over how to transform the American color line.

In our view, the persistence of racial inequality stems from the long-term effects of labor market discrimination and institutional practices that have created cumulative inequalities by race. The result is a durable pattern of racial stratification. Whites have gained or accumulated opportunities, while African Americans and other racial groups have lost opportunities—they suffer from disaccumulation of the accoutrements of economic opportunity. Rather than investigating racial inequality by focusing on individual intentions and choices, we concentrate on the relationship between white accumulation and black and Latino disaccumulation. (22)

- Today’s very large gap in median net worth between whites and African Americans is mostly due to the discrepancy in the value of the equity in their respective homes. Blacks experience more difficulty obtaining mortgage loans, and when they do purchase a house, it is usually worth less than a comparable white-owned home. White flight and residential segregation lower the value of black homes. As blacks move into a neighborhood, whites move out, fearing that property values will decline. As whites leave, the fear becomes a reality and housing prices decline. The refusal of white Americans to live in neighborhoods with more than 20 percent blacks means that white- owned housing is implicitly more highly valued than black-owned housing. Redlining completes the circle: banks refuse to underwrite mortgage loans, or they rate them as a higher risk. As a consequence, when black homeowners can get a loan, they pay higher interest rates for less valuable property. This results in disinvestment in black neighborhoods and translates into fewer amenities, abandoned buildings, and a lower property tax base. Because white communities do not suffer the consequences of residential disaccumulation, indeed they receive advantages denied to black homeowners; the value of their housing increases and they accumulate wealth. In this way interlocking patterns of racialized accumulation and disaccumulation create durable inequality. (23-24)

- Racial realists believe that the accumulation of wealth and power by white Americans over the past 360 years is irrelevant to current patterns of racial stratification, and the use of race-conscious remedies to redress past racial injustices is therefore unnecessary and unfair. As they see it, basing current policies on past practices is wallowing in the past. The main impediment to racial equality, they feel, is state-sponsored discrimination, and the civil rights movement put an end to that. Thus, past discrimination should not matter. Ironically, adherents of this point of view ignore a different form of state-sponsored racial inequality—the use of public policy to advantage whites. Racism is not simply a matter of legal segregation; it is also policies that favor whites. (25)

Quotations from Aliya Saperstein’s “Can Losing Your Job Make You Black?”[4]

- Although the changes in race that appeared to be caused by any given change in social position were small, all the life outcomes we examined, including college graduation, teen parenthood, and welfare reception, affected changes in racial classification. Moreover, a cascade of woeful events could add up to a notable alteration in someone’s “race.” Take a hypothetical 29-year-old father of two who was classified as white by an interviewer. If he spent time before the next interview in jail, became unemployed, got divorced, and fell into poverty, his likelihood of being seen by an interviewer as white the next time dropped from 96 percent (random fluctuation, given no changes in his social position) to less than 85 percent. For positive experiences, the effects are in the opposite direction.

These changes line up in ways that reflect widespread racial stereotypes. Interviewers became likelier to see someone as black the more the respondents’ situations fit the stereotype of black people—and vice-versa for white people.

The studies we have conducted show that while race shapes our life experiences, our life experiences also shape our race. Race and perceptions of difference are not only a cause of inequality, they also result from inequality. Americans’ racial stereotypes have become self-fulfilling prophecies: the mental images Americans have of criminals and welfare queens, or college grads and suburbanites, can literally affect how we see each other.

Why Do We (Still) Care About Race & Ethnicity?

At this point you might be asking, why do we care about race? Aren’t we making racial divisions in society worse by talking about them? After all, didn’t we deal with these problems during the Civil Rights Movement? If races are socially constructed, can’t we just stop constructing them?

These are all legitimate and important questions because they help us understand that just as thinking about race only in terms of individual identity doesn’t work, neither does thinking about racism only in terms of individual hatred or prejudice. Consider an example from Moya and Markus, in which a City Council proposes to build a chemical plant in a particular part of town that has a higher percentage of African American residents. If they were to justify their decisions, the City Council leaders would explain their choice of where to put the plant was based on land costs, distribution of jobs, and political pressure from particular constituencies.

They would likely respond negatively to accusations of “racism,” and defend themselves as not being racist, and not thinking about race at all in their decision. However, as Moya and Markus argue, racially disparate impacts do not require individuals to have thought about race consciously at all. Instead, we return to how race structures our society: to say that race is a social construction is not to say that it is not real. Indeed, we see its reality all around us in how it affects the life chances and opportunities of each of us.

Furthermore, there are concrete impacts of our nation’s history of slavery and legal discrimination, of which Jim Crow is the most visible example. Until the mid 1960s, racial discrimination was the law of the land, and social programs, subsidies, and governmental actions were structured explicitly along racial lines. These structural impacts continue to reverberate in the distribution of wealth and opportunity in American society.

Now, you might ask, why do these inequalities still exist in society? What perpetuates them? After all, laws that included racially discriminatory language were banned by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, right? Yet, as researchers have demonstrated, members of different racial groups continue to experience American society in vastly different ways. This is true despite the fact that once-legal forms of discrimination are now illegal. Scholars in a range of disciplines have spent several decades attempting to figure out exactly why and how this occurs. (In fact, your research for the Informative Report will profit from this scholarship.) Indeed, what these researchers have found is that just because identity categories are socially constructed and not biological in basis does not mean that they don’t affect each of us as individuals. Certainly, we need not be conscious of how we are doing race to continue to do it. This is what the Duke University sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva memorably called “racism without racists.” What he means is that there is no need for someone to make explicit racial judgments for racial hierarchies to be reproduced.

Partially, this is the result of what psychologists call “implicit bias,” which is the product of the various stereotypes, images, representations, and so on that are all around us and that alter how we think about people of different races (even if they are people of our own race). Recall Saperstein and Penner’s research mentioned earlier in this chapter. In the cases of researchers relabeling individuals over the course of their lives, it is not that the skin color of any individual has changed, but rather the lens through which they are viewed that has changed. The fact that people’s race can “change” over time helps us understand that race is a constructed category that shifts. This is true even if the researcher doing the marking is unaware of their shifting perceptions. “Implicit bias” occurs in ways of which the individual is not conscious. The actions of the researchers in differently marking interviewees’ racial identity following particular life events reflect broader societal stereotypes and biases, rather than individual dislike or hatred.

The effects of “implicit bias” can be found throughout everyday life and even in your college classrooms. In a well-known study, Donald Rubin’s “Nonlanguage Factors Affecting Undergraduates’ Judgments of Nonnative English-Speaking Teaching Assistants,” undergraduate students’ perceptions about their Graduate Teaching Assistants’ “foreignness” affected how they rated the GTAs’ understandability and communicative ability – even in situations in which the voice used in the lecture was that of a native English language speaker.

Invention Strategies: Getting Started & Choosing a Specific Issue

The theme of your informative report will be a problem or issue related to race and ethnicity in the United States. You have a wide variety of issues to explore, and you may want to consult local, regional, or national news stories and events; consider the ways in which race and ethnicity play out in your academic major or career interests; explore your own interests; or, investigate larger institutions that may play a role in social inequities in which race and ethnicity play an important factor; some of these institutions are insurance, medicine, education (standardized testing, etc.), justice, policing, banking, voting, governmental policies, and prison systems.

Here are five examples of topics that have important consequences for people and that will allow you to explore a range of causes.

- Black Farmers. The issue of Black Farmers is one that your readers may know very little about; in 1910, black farmers represented 14% of all farmers in the United States; currently, they represent only 1.4% of the total. Roxana Hegeman, in “‘We are Facing Extinction’: Black Farmers in Steep Decline,” investigates several of the systemic causes for this drop in the number of black farmers; for example, she describes the history of loans given by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which were biased in favor of white farmers.[5] Given the history of black farming in Nicodemus, this issue may interest your readers who are looking for topics set in Kansas. Another related issue are problems that have been caused in attempting to provide funding to historically “socially disadvantaged farmers” to support farmers who are from ethnic minority groups; white, conservative farmers have claimed that these debt relief programs are giving these farmers an unfair advantage (Healy).[6] The Kansas Black Farmers Association website may be another source to explore this issue, its challenges, and its causes.

- Native American Students & College Education. In an editorial by James Bryant, “Acknowledge—and Act,” he defines an important issue that links Native American students with universities and colleges. He reminds college administrators and educators about some of the statistics related to Native American students at the university level; for example, “just 19 percent of Native Americans aged 18 to 24 are enrolled in a college program, compared to 41 percent of the overall population.” Moreover, only 41% of Native American students do eventually graduate from their degree programs.[7] Your readers will be interested in hearing about what are some of the immediate causes of these lower participation and graduation rates, which may include economic stability, cultural attitudes, and the effects of the coronavirus pandemic; additionally, readers will expect to hear about the historical, systemic challenges to Native American education, such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs schools that followed a policy of separating Native American children from their linguistic and cultural heritages.

- African American Urban Neighborhoods & Higher Temperatures. Research has been conducted on how the living environments of poor people as well as those of people of color are different from those of white, middle-class Americans. In a New York Times article about differences in temperatures between black and white neighborhoods, Brad Plumer and Nadja Popovich point to “redlining” government policies in the 1930s, which made it impossible for homeowners to receive loans in these areas; historically redlined neighborhoods, according to this research, have far fewer trees and more asphalt, with the consequences that these neighborhoods are five or more degrees hotter than those of more affluent neighborhoods.[8]

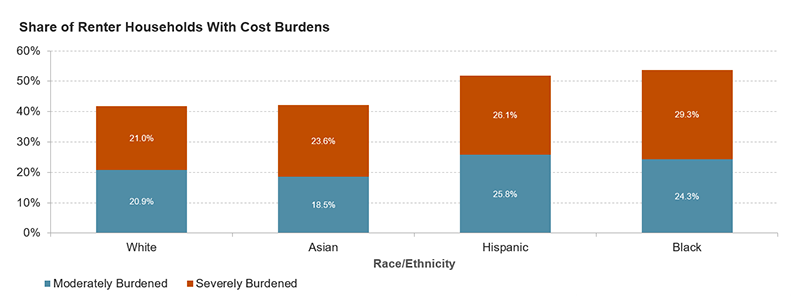

- Race, Ethnicity, Poverty, and Housing Challenges. Sophia Wedeen’s report, “Black and Hispanic Renters Face Greatest Threat of Eviction in Pandemic,” includes the following graphic that shows how apartment renters based upon their racial or ethnic identity face different levels of “cost burden rates”; either they are “severely burdened,” meaning that 50% of their income goes to paying rent, or they are “moderately burdened,” in which 30% of their income goes to covering rent.

The cost burden has increased and did so dramatically during the coronavirus pandemic, changes which Wedeen explains were caused by the fact that Latino and Black renters had jobs that were much more impacted by the pandemic-related economic downturn.[9] Your readers would be interested in your investigation of the other causes for why over half of African American and Latino renters are moderately or severely burdened by their rent payments.

- Asian American Film Representation. A blog by Nicole Park, “The Importance of Authentic Asian American Representation in Hollywood,” describes a problem: the lack of representation of Asian American characters in Hollywood films and, when there are actors of Asian ethnicity, the use of stereotypes, which can have negative consequences for young viewers.[10] Although Park does not explore causes to this problem, your readers will be interested in how you could explore economic, cultural, or other causes to this problem.

Research Strategies: Narrowing the Scope of Your Issue

Before deciding how to narrow your topic, you should write down what you already know about the issue, helping you to begin to construct a general picture of the topic itself. You can then do some preliminary library or Internet research, especially if it is a topic that you don’t know much about. This preliminary research itself can help you hone a more specific focus for your report and for the kinds of research you will continue to conduct.

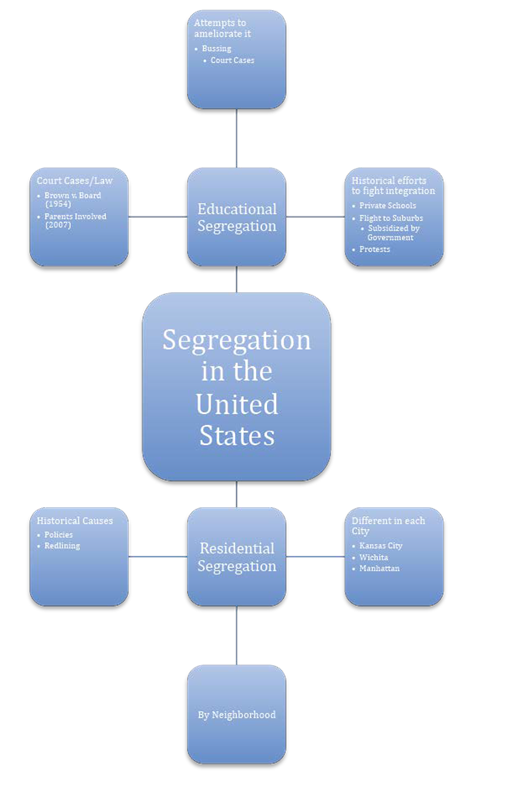

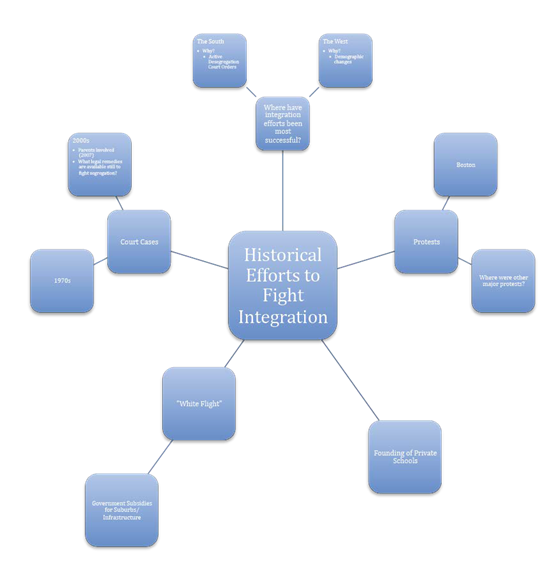

Another way to help you focus your ideas is to use a cluster diagram, which can be particularly useful for students who benefit from more visual or graphic learning styles. Below is a very brief cluster diagram on the topic of “Segregation in the United States.” As with most topics, the cluster diagram starts with a broad issue (which you see in the largest box in the middle) and then explores related themes and topics in the branches that radiate out from the middle box. You’ll notice that each associated topic is connected to a larger node, creating a number of thematic clusters (hence the name “cluster diagram”). There is no right or wrong way to create a cluster diagram, but they are most useful when related topics are clumped together, allowing smaller, more specific questions or pieces of information to branch off into as many related nodes as possible. In doing so, a cluster diagram can help you find a new focus or narrow a broad topic into one that is more manageable for the scope of your Informative Report.

A cluster diagram like the one above on the topic of “Segregation in the United States” still leaves the researcher dealing with a too-broad topic. The next step is to pick a particular spoke of the cluster diagram and focus in on narrowing that topic. In this case, let’s choose to focus on “Historical Efforts to Fight Integration.”

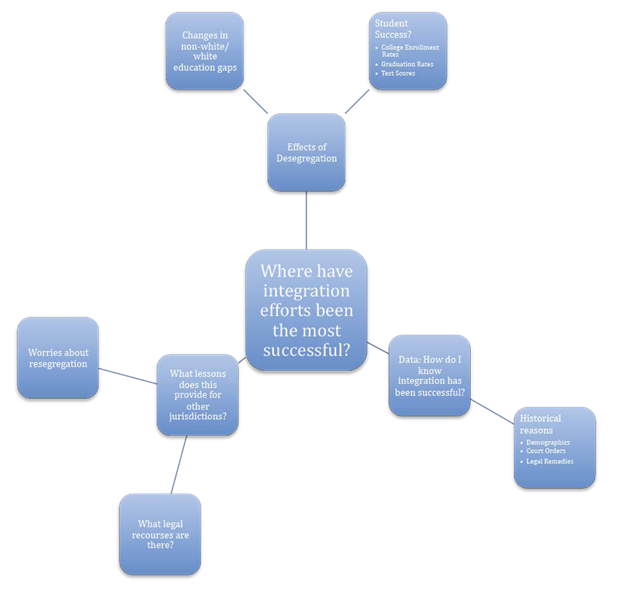

Even after more fully developing this new cluster diagram, we find that, once again, the topic remains too broad. Often, it will take several steps of narrowing to reach a topic that is both narrow enough for 5–8 double-spaced page memo and which can be effectively researched. Let’s take another spoke and narrow the topic further around the question of “Where have integration efforts been the most successful?” Notice that as you narrow your topic, you also must begin to research around these more specific and answerable research questions. Each process of narrowing requires more research. In other words, to be successful in this report, you cannot simply find several outside sources and have that be the end of your research activity. Research is a cyclical process, one that leads to more questions, which leads to still more research, which leads to still more questions, and so on. Ultimately, the sources you choose to cite in your final Informative Report should be only a part of the total research that you conducted and should clearly fit within the narrow topic you ultimately decide on.

Activity

With your classmates, look at these following three broad issues. Practice the clustering strategy to narrow down one of these issues so that is more manageable for you and more useful for interested readers.

- Immigration

- Poverty & Minority Ethnic Groups in the United States

- Social Inequality During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Research Strategies: Generating Research Questions

Drawing on the information you have gained from completing the clustering and group invention activities, you should be ready to formulate a primary research question. Research questions are important because they help you focus your research efforts. Instead of collecting every source you can find on the topic—or collecting only sources that support a pre-formed opinion—you will look for sources that help you answer specific questions, therefore helping you to focus your report as you write. Strong research questions are those that are interesting and significant to both you and your audience.

The difference between an issue and a research question is focus. Consider the difference between the issues and research questions below.

Issue: Housing Segregation in Kansas City

Research Question: What is the effect of housing segregation on access to K-12 education in Kansas City?

Issue: Wealth differences between African Americans and other minority groups

Research Question: Which social structures most influence wealth differences among groups?

Keep these templates in mind as you formulate your research question:

- What is the role of race and ethnicity in X?

- For example: What is the role of racial demographics in determining the composition of police departments?

- What are the negative consequences of the issue or problem? In short, how does race and ethnicity affect X?

- For example: What effects do racialized mascots have on Native Americans?

- What are the major causes of this problem related to race and ethnicity?

- For example: What are the historical, economic, and institutional reasons why Asian- American characters have been so underrepresented in Hollywood films?

- Who is most affected by the issue or problem? How are these groups affected?

- For example: Who is most affected by the large percentage of families in the United States who struggle to pay their rent?

- What have been some attempts in the past to confront this issue? Why have these attempts failed?

- For example: How has the U.S. government attempted to support black farmers in the past? How successful were these attempts? What were some roadblocks to these programs and policies?

Once you have formulated a list of potential research questions, answer the questions below to test their feasibility and choose the most productive focus for your informative memo.

- Will your audience be interested in this question? Why?

- Is the question significant for the audience? In what way(s)?

- Is the question limited enough for a 5–8 page memo?

- Is there a reasonable possibility of finding information about this topic in the time you have available? What might be some good sources of information to answer this question?

If you answered “no” to any of the above, you might need to find a new focus and a new primary research question.

Research Strategies: Considering Your Audience

Remember that, for this assignment, you are writing to a public official, rather than to your professor or your classmates. The research that you do will change based on your target audience, so it is important to narrow your topic and your research by figuring out who that audience is. To do this, think about the communities that you are a part of. As we have been discussing this semester, each of us is a part of many communities simultaneously. For example, you are a member of the Kansas State student body. If you reside on campus, you are not only a member of your campus community, but also a part of the city of Manhattan, Riley County, the 66th District of the Kansas State House of Representatives, and the 22nd District of the Kansas State Senate—and that just covers the state and local levels of government. Part of being an active citizen is participating in the political process on each of these different levels, and thus representatives of each of these communities (and more) are a potential audience.

One of the most important parts of writing to a specific audience is determining the needs of the audience before you plan what you will write. Knowing about your audience helps you understand what kind of information will be most valuable to them. Audience awareness also helps you to determine the tone and style of writing you will use. For this report, it may even be true that your audience knows something about your topic. However, the work of a public official covers many areas and they are very busy; often, it is only by being made more aware of information that they may act. Instead of thinking about the process of “informing” as just providing something new and surprising to an audience that knows little or nothing about your topic, think of yourself as a someone who is doing the work of collecting the different information available about that topic and reporting back. For example, a Congressperson putting together a hearing on “Housing Segregation by Race” is likely aware that segregation is an issue today. However, they still will ask the Congressional Research Service to provide a report on the available research and up-to-date information on the topic prior to the hearing.

Think of yourself as playing the role of a researcher in the CRS, providing as comprehensive a report as possible to a public official so that they have a synthesis of the information available to them.

Some students will find that they have a clear sense of what community they want to research— and therefore which target audience they will direct their research toward—before they have decided on a more specific or narrow topic. If you fall into this category, you might use the “thinking frames” activity below to help you find a clearer focus within the broad category of racial inequality within the U.S. Other students, however, might need to narrow their specific topic before determining the appropriate target audience. If that’s where you find yourself at this moment, you might want to skip ahead to the cluster diagrams below, returning to these thinking frames when you have a better sense of your intended audience.

These three following “thinking frames” can help you begin to think about how your topic is significant for your audience:

- My audience knows little about my topic, but it is important to them because…

- My audience has a misconception about my topic, but I can show them that…

- My audience does not see how my topic relates to them, but I can show them how it does…

Conducting Research and Finding Sources

Your instructor will give you information about how to find sources of information using Hale Library’s databases and catalog. Additionally, you will be asked to complete the online Library Assignment. You may also be required to complete some additional exercises on finding sources, like the activity later in this section. Once you have started your research, you will need to determine if the sources you find are credible and relevant. You should use the following guide to the “Big 5” criteria to evaluate your sources.

The “Big 5”: Evaluating Web and Print Sources for Research Potential

Nancy Trimm

What does it mean to evaluate sources for research potential?

Evaluating both print and web sources for research potential means you must hold those sources to the highest standards. To write a credible, thorough research paper of any kind, you must use only the most credible and relevant sources available.

Determining the credibility of a source requires a bit of detective work. When you apply the “Big 5” criteria, you may uncover hidden motivations, new purposes for writing, unexpected authors or sponsors, and exciting research discoveries.

Why is it important to evaluate sources?

Using unreliable and discredited sources will weaken your writing and erode your credibility. To write with authority and credibility, you must demand the same from your sources.

What kinds of skills will I develop?

By successfully evaluating a source and determining whether or not it is credible or relevant to your research, you will be practicing critical thinking skills. Critical thinking skills are essential to your development as a writer and a thinker.

Where do I begin?

Before locating possible credible sources, you should ask a few questions.

Why am I writing?

To inform? To persuade? To explore an unfamiliar subject? To reflect on a personal experience? To entertain? To enlighten?

What sort of information am I looking for?

Facts and statistics? Historical perspectives? Opinions and editorials? News and information? Personal narratives? Scientific studies and research?

Where should I look?

Deciding what kinds of information you are looking for will help determine where to begin looking. Newspapers provide information on current events, whether local, national, or global. They also offer op-ed pieces designed to express a particular opinion or perspective. Academic journals offer critical analyses, reports, scholarly interpretations, and in-depth research on a variety of topics ranging from medicine to politics to psychology. The Internet can provide immediate access to a wide variety of links and a vast array of information. Government records detail census reports, legislation, and various other government policies and regulations.

The library is not only filled with journals, newspapers, books, dissertations, surveys, and reports, but also with knowledgeable, helpful people anxious to assist you with all of your research needs. Don’t be intimidated. Ask for help!

What are the “Big 5” criteria for evaluating sources?

1. Authority

Identify the author or Web page sponsor and publisher.

Does the sponsor and/or publisher identify his or her credentials? Does the author list his or her qualifications? Is the source an advocacy group? If so, what are they advocating? Is the source a commercial enterprise? If so, what are they selling? Is the source an educational institution? Is the source a local or state government? A national government?

2. Accuracy

Locate contact information for the author or webpage sponsor.

Locate the source of the article or site’s information. Is the information original or taken from someplace else? Can you verify this information?

3. Objectivity

Determine the author or website’s purpose.

Is the purpose to inform? To advertise? To persuade? To entertain? To explain? Knowing why a site or article was written is a crucial step in determining whether or not the information meets your research needs.

4. Coverage

Determine whether or not the article or site’s information is thorough and comprehensive.

Is the information you are seeking covered in enough depth to be useful? Is the topic of the article or site clearly presented? Are all claims supported by sufficient evidence and explanation? Do you expect more or different information given the title and opening remarks?

5. Currency

Identify the date the article or site was produced.

Is the information current enough for your purposes? If evaluating a webpage, when was the page last updated? Are the links current? Does the page contain many dead links?

What do I do once I determine whether or not a source fulfills the “Big 5” criteria?

If a source fulfills all “Big 5” criteria, you should feel confident in the credibility of that source. Use the source to provide context, explanation, evidence, and/or support for your essay’s claims. Always avoid letting sources do all the speaking for you. Find your own writer’s voice and speak with authority! The most important voice in your essay is your own!

Research Strategies: Note-Taking Review

Taking notes is an important, yet often overlooked, part of conducting research. By taking accurate and detailed notes, you will be able to present a cohesive report that will be useful to your reader. If you don’t take notes, you may find yourself reading and rereading the same article several times as you look for a piece of information. You may also have problems with plagiarism if you don’t carefully monitor what you have quoted or paraphrased from your sources.

The best method to use for taking notes is to read your sources rhetorically, meaning that you try to understand your sources’ arguments while considering how you might use the sources when writing your paper. It’s a good idea to use a journal to take notes as you read. You can keep a research journal in a notebook, on your computer or tablet, or even on your smartphone. Most research journals are divided into two columns. In one column you can make notes about the author’s main ideas, unfamiliar words, and other important parts of the article. On the other side of the page, make notes about how you plan to use the source in your writing.

Another way to take effective notes is to annotate a source as you read it. Annotating a source means to write notes in the margins as you read, paying attention to questions you have, the author’s main ideas, unfamiliar vocabulary words, and how the ideas in the article connect to one another. If the margins of the source are small or you need more room, you can use sticky notes to write on and attach them to the appropriate part of the article. Below is an example of possible annotations for the first three paragraphs of Aliya Saperstein’s article, “Can Losing Your Job Make You Black?”

| Text | Annotation |

|---|---|

| Most Americans think a person’s race is fairly obvious and unchanging; we know it the minute we meet him or her. Similarly, most academic research also treats race as fixed and foreordained. | She immediately signals audience assumptions that she will refute through the article. |

| A person’s race comes first and then his or her experiences, education, job, neighborhood, income, and wellbeing follow My research with sociologist Andrew Penner on how survey respondents were classified by race over the course of their lives, calls into question this seemingly obvious “fact.” | This is the article’s thesis, which states that the evidence collected by her and Penner refutes the idea that race doesn’t change over one’s lifetime. |

| The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth has been following a group of about 12,000 Americans since they were teenagers and young adults in 1979. From 1979 to 1998, the survey interviewers had to identify the race of the people they interviewed, even when those people had been repeatedly interviewed. | Where she got her evidence: A longitudinal study follows a group of people over the course of many years to study life changes. |

| At the end of each session, interviewers recorded whether they thought a respondent was “Black,” “White,” or “Other.” Here is the surprise: nearly 20 percent of respondents experienced at least one change in their recorded race over those 19 years. | Their key finding: researchers marked some people’s race differently in the study for nearly 20% of those studied. |

| These changes were not random, as one might expect if the interviewers were just hurrying to finish up or if the data entry clerks were making mistakes. The racial classifications changed systematically, in response to what had happened to the respondent since the previous interview. |

Saperstein says that how researchers marked the race of research subjects was based on things that had happened in their lives not just skin color. |

Activity: Talk It Out

Bring the research you’ve gathered, read, and annotated to class. Work with a partner and ask your partner the questions below. Make sure to listen carefully and to take notes on your partner’s responses. Play the role of a doubter, asking follow-up questions as needed, to help your partner develop his or her research.

- Why do you think your audience will be interested in this topic?

- What goal/purpose will be served by this report—for this particular audience?

- What source seems most relevant to your purpose? Why?

- What source seems least relevant to your purpose? Why?

- What further research might be necessary to fulfill your report’s purpose?

Writing Strategies: Developing a Thesis

Remember that the purpose of your paper is to inform your audience about an issue they may have a misconception about or to broaden their perspective on a particular issue. To relate this purpose to your audience, you should carefully construct a thesis statement that communicates the topic of your paper and connects this topic to the audience’s needs. While we often think of thesis statements as making an argument, they can, instead, provide a sense of the controlling idea of the text that is to follow, illustrate why the information is relevant to the reader, or make clearer the larger significance of the information. And while you might have learned that a thesis statement should be only one sentence, in fact, sometimes a thesis idea is expressed in more than one sentence. In this case, your thesis should answer the question: How does this issue relate to the interests of my audience?

You might also have learned that you should have a clear sense of your thesis statement before conducting research. However, this is rarely good advice. How are you supposed to know your findings before you do the research? That is why you find the information about constructing a thesis statement here, near the end of the chapter. Now that you have conducted some research and narrowed your topic, you can return to the ideas introduced earlier on how to relate your topic to your audience. This time you should have a clearer sense of the topic itself, the information you have found on that topic, and the specific audience to whom you are directing your report. These frames can now help you structure your thesis in relation to your audience:

My audience knows a little about X, but I can help them learn more.

Example. The President of Kansas State is aware that there are different educational outcomes (such as graduation rates) for African American students and white students on the Kansas State campus. This memo will explain some of the causes of these disparate outcomes by examining the effects of educational segregation and disparate funding in Kansas at the K-12 level. Knowing about this information will allow the President of K-State to take it into account as they attempt to correct these different outcomes.

My audience holds a misconception about X, but I can help to change their misconception.

Example. The President often gives speeches in which he tells members of the black community that young people have to take responsibility for their own success in life by going to school and working hard. However, my research shows that individual hard work is much less important than structural issues such as poverty, access to resources, and residential/educational segregation. Knowing this will allow the President to highlight policies addressing these structural issues rather than focusing on individual hard work.

My audience doesn’t see that X relates to them, but I can show how it does relate to their needs.

Example. Many Congresspeople don’t see how race affects the proximity of so many communities of color to environmental pollutants in cities. My research shows that such communities of color are adversely impacted because of segregation and a perceived lack of political power despite decisions appearing to be made without mention of race.

Writing Strategies: Organizing Your Report

The organization of your report should make it easy to read and understand. In addition to following memo format, you should also consider the expectations that most audiences have for reading an informative report. These expectations include the following:

- An introduction that states your main purpose and thesis, explains how the issue is relevant to your audience, provides any necessary background information, and briefly previews the points to be discussed.

- Body paragraphs that include clear topic sentences, present examples from the source material, and include an explanation of how these examples relate to your main point and connect to your audience’s needs.

- A conclusion that can either restate the main points of your report, pose new questions that the reader may pursue later, discuss the possible implications of your research, or present a call for action.

Writing Strategies: Forecasting Your Organization

In your introduction, you should forecast your organization to make your research report more readable for your audience. You can also give them cues about how the report should be read and how you will structure their reading experience. Think of these organizational cues as “traffic signs” or “road maps” to guide your readers.

Your thesis statement is one important organizational cue in which you explicitly tell your readers your overall point. You can also provide a purpose statement in which you give your readers the reason they are reading the report and list for them your overall goals. Additionally, you can provide a blueprint statement that directly tells readers about the structure of the report. The blueprint statement may act like a table of contents, telling readers what the major sections of your report will be.

Writing Strategies: Using Academic Language & Style to Talk about Race and Ethnicity

Each of us is always “doing race” at every moment, regardless of whether we are thinking about it or not. As writers, that means that your own work on this report is part of the same processes that we are studying and researching. As you write your informative report, you are also “doing race.” Consequently, the words you choose, the research you conduct, and the writing you perform are all part of that process of “doing race.” This is especially true of the racial terms you use to write about your topic. Earlier in the chapter, we looked at previous Census categories for race, such as “quadroon” and “octoroon” from the 1890 Census that no longer are meaningful. As the policies, structures, and cultures of society change, so does the terminology that we use to label racial groups. Often, this is the result of specific groups deciding what they would like to be called and which terms are offensive. Consequently, how we label members of groups is a matter of basic respect and formality. In the past, terms such as “Negro” or “colored” or “oriental” were considered acceptable. However, now they are considered insulting and denigrating. In your own writing, you should therefore always seek to be as respectful as possible, using the most appropriate terminology at the moment you are writing. Consequently, instead of the words mentioned in the previous sentences, you should use terms such as “African American,” “black,” “Asian-American,” or “Latina/o” as you draft and revise your informative report.

Writing Strategies: Writing Your Abstract

Your abstract provides a synopsis of your informative report; readers should be able to scan your abstract quickly to determine whether it will be useful for them. Your abstract should be approximately 100-200 words long, and it should focus on the important keywords that make up your report and that were used in your research process.

Your abstract should include a one-sentence summary of each of the sections of your report, including the following:

- Your overall issue, problem, or research question

- Your most important findings

- Your most important points of significance

Here is one example of an abstract, which is from Donald Rubin’s research study, “Nonlanguage Factors Affecting Undergraduates’ Judgments of Nonnative English-Speaking Teaching Assistants”:

Abstract

In response to dramatic changes in the demographics of graduate education, considerable effort is being devoted to training teaching assistants who are nonnative speakers of English (NNSTAs). Three studies extend earlier research that showed the potency of nonlanguage factors such as ethnicity in affecting undergraduates’ reactions to NNSTAs. Study 1 examined effects of instructor ethnicity, even when the instructor’s language was completely standard. Study 2 identified predictors of teacher ratings and listening comprehension from among several attitudinal and background variables. Study 3 was a pilot intervention effort in which undergraduates served as teaching coaches for NNSTAs. This intervention, however, exerted no detectable effect on undergraduates’ attitudes. Taken together, these findings warrant that intercultural sensitization for undergraduates must complement skills training for NNSTAs, but that this sensitization will not accrue from any superficial intervention program.

Evaluation Criteria

As you revise your informative report and share it with your classmates, consider the ways in which you have met the major expos criteria:

Purpose & Focus

A strong informative report focuses on an interesting and significant issue or problem related to race and ethnicity in the United States; you have chosen an issue that will be meaningful to a public audience and help their understanding about social problems that are structured by race and ethnicity. You provide a clear and engaging thesis statement to focus what you will be researching.

Development

You have satisfied your readers by using at least five secondary research sources to help them understand the social problem more; your research sources will be regarded as credible and authoritative by your readers. Your audience will have a clear understanding about the structural and systemic causes and consequences of the problem.

Organization

You guide your readers skillfully through your informative report, and you signal your thesis clearly. You use different sections, headings, topic sentences, and transitional phrases to differentiate the different causes you are exploring. You effectively signal when you are contributing research from secondary sources as opposed to when you are adding additional explanation or background.

Tone & Style

You adopt a formal and academic tone, using MLA citation style or another citation system consistently. You show objectivity and treat your research issue and audience with respect. You use academic concepts and terminology, especially when you are talking about race and ethnicity.

Activity: Peer Review Workshop Activity

This workshop requires four partners to read your report and provide you with revision suggestions for different parts and criteria of this assignment.

Reader Role #1

Test the introduction. After reading the introduction, circle the writer’s thesis statement. If you can’t find the thesis, try to figure out what it will be and write it down in the margin. If the thesis does not seem to be relevant to an issue or problem related to race and ethnicity in the U.S., please note that down.

Based on the header and introduction, who is the intended audience? Why would they care about this specific topic? Note this information down. If you can’t tell who the intended audience is or you may not feel that the audience is appropriate, suggest a few target audiences who might care about this information.

On a scale of 1–5, how well does the writer forecast what will happen in the body of the informative report?

What else can the writer do in the introduction to make it easier to read the report?

Reader Role #2

Test the first body paragraph. Skim the introduction to get the gist of the report, and then carefully read the first main body paragraph. Circle the main point or topic sentence. Put [brackets] around the examples the writer uses.

Does the writer explain how the examples are relevant for the intended audience? If not, note that for the writer in the margins of the report or in the space below. If you have time, you might provide some suggestions for how to better explain the relevance of the example(s).

Do all of the examples relate specifically and explicitly to the topic sentence of the paragraph? If not, list below the examples that don’t belong in this specific paragraph. It’s also possible that the examples seem to belong together, but the topic sentence needs to be revised to better reflect what the paragraph is actually doing or saying. If that’s the case, note this problem in the space below.

What does the writer say about the relevance of the information to the intended audience? Does this seem convincing to you as a reader? Are there other reasons that the target audience might be interested in this information?

What is the strongest point or the most useful information in this paragraph? Why is it the strongest point?

What are two specific ways in which the writer could improve this paragraph?

Reader Role #3

Test the focus and organization. Read the circled topic sentence and then quickly read the remaining body paragraphs.

Within each paragraph, how well does the writer explain how the sources connect to the main point of the report? Note here any places where the connections need to be clearer, more explicit, or more developed.

Indicate in the report where you get lost or confused about what the writer is trying to say. Note or highlight the transitional words that you find. What additional transitions are needed?

If the writer has included a forecasting statement in the introduction, does the organization of the report follow that roadmap? If not, note how it diverges in the space below.

Reader Role #4

Test the citation style and tone. Examine the body of the report solely for how the writer introduces facts and quotes, looking specifically for attributive tags. Remember that attributive tags are places where the writer introduces a source and might include the author’s name and credentials, as well as the title of the article, book, or report.

Overall, how well does the writer introduce quotes or paraphrases? Rank the writer’s integration of sources on a 1-5 scale. Remember that writers should avoid “dropped quotes” where there are no attributive tags. Make notes in the margins where more attributive tags are needed.

Write “citation?” in places where you think the writer needs to include parenthetical information about the source. Remember that any information that is not the writer’s original work must be cited both within the report itself and on a works cited page. This is true whether it is directly quoted or paraphrased.

Write “tone?” in the places where you think the writer is no longer providing a balanced account of the issue, but instead is arguing for one side of the issue over another. If the writer is too informal or sounds combative or dismissive, you should also note the tone.

On a scale of 1–5, how appropriate is the writer’s tone for a formal informative report?

Revising Your Report

First, read over your classmates’ notes on your report and ask them for clarification, if necessary. These notes, of course, provide you with only a starting place for revising your report.

Remember that that you should think of revision not as simply changing a few words or moving a sentence or two, but often as rewriting full sections in order to clarify purpose, focus, and organization; conducting new research to more fully develop important points; reworking your tone and style in order to better match the audience and purpose; restructuring for clarity of organization; deleting sections that do not fit the overall purpose and focus; adding new sections that better develop your informative goals; etc. Given the goals of this assignment, you will want to pay particular attention to places where your classmates noted that they were confused or needed more information, as well as places where they marked “tone” in the margins but, again, these are only starting suggestions for larger revision.

Citing and Editing Your Report

Once you have fully revised your report, you can turn to the final editing process. Before you print out your report, check your Works Cited (or References) section to make sure it follows MLA or another citation style. Have you:

- Capitalized the titles of articles and books, and the names of websites?

- Italicized the titles of books and websites and put the titles of articles in quotation marks?

- Included parenthetical in-text citations for all information from every outside source, even if the information is paraphrased?

- Put all direct (word-for-word) quotes in quotation marks?

- Avoided referring to authors solely by their first names?

- Placed citations on the Works Cited in alphabetical order according to the first word in the citation (usually the author’s last name)?

- Included your access dates for websites?

- Double-spaced your Works Cited and indented ½ inch after the first line of each entry? (i.e., used hanging indentation)

- Made sure that each parenthetical citation in your report also appears on the works cited page? Also make sure that everything that appears on the Works Cited is also listed in the report itself.

Finally, before you print out your report, make sure you read through it carefully for errors and typos.

Student Examples

Effects of Race on African American Male Student- Athletes in Division I NCAA Schools

Ashton O’Brien

Ashton O’Brien wrote this informative report in Kirsten Hermreck’s Expos I class. It won first place in the 2017 Expository Writing Program Essay Award Competition.

To: Mark Emmert, NCAA President

From: Ashton O’Brien

Cc: Ms. Hermreck

Subject: Effects of Race on African American Male Student-Athletes in Division I NCAA Schools

Introduction

The United States has historically been a nation comprised of various ethnic groups, but early in the nation’s history the white race established dominance over Africans through slavery. This racial hierarchy was the reason behind segregation of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) and Predominately White Institutions (PWI). In 1954, this all reformed when Brown vs. Board of Education ruled racially segregated schools unconstitutional. Although PWIs were still reluctant to embrace African American students attending their institutions, they were exceedingly open to recruiting black athletes to improve their collegiate athletics (Curette 472). Many Americans are unaware of how race is still an issue in NCAA collegiate athletics. Understanding the connection between the racial demographics of Division I athletics within NCAA institutions and the African American racial stereotypes in collegiate athletics and its effect on the student-athletes is important for you as the NCAA President to be able to improve the inclusivity of your athletics program. In this brief report, I will share information regarding the racial demographics within the NCAA, African American stereotypes in athletics, and the resulting effects on student-athletes.

Racial Demographics

As the President, you already know that the NCAA has noticeably equalized its ratio of white to black male student-athletes in the last fifteen years. According to the NCAA database, the percentages of African American males increased in Division I basketball from 55 percent in 1999-2000 to 57.6 percent in 2015- 2016. A more significant increase was in NCAA Division 1 football with the percent of African American male athletes jumping from 39.5 percent in 1999- 2000 to 47.4 percent in 2015- 2016. By comparing the past and present racial demographics, it is evident that your efforts as NCAA’s President to ending segregation within Division I athletic programs are effective, especially in narrowing the racial gap of Division I athletes. This information displays how in just fifteen years the ratio of black athletes has become equal or exceeded that of its white counterpart, but the administrative positions of the institutions that your association regulates do not expression this same pattern.

Although the NCAA has made great strides in creating a more inclusive environment for the athletes that participate in Division I football and basketball, the administrative positions of PWIs in the NCAA are greatly lagging behind. The scholarly article, “Significance of Race in College Athletics” by Chase Smith, demonstrates the significant difference of race by addressing the 2012 Racial and Gender Report Card within college sports reported by The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports. This report displays the wide racial gap that is present in the administrative positions within PWIs. The majority of commissioners, presidents, athletic directors and head coaches of these institutions are white, while less than 15 percent of these positions are held by African Americans (Smith 398). These results shown in Smith’s article make it very evident that racial segregation and the hierarchy of white dominance over black are still present within the institutions your program regulates.

These unbalanced racial demographics at the administrative levels of these institutions’ athletic programs could have possible implications on the inclusivity of NCAA programs. A possible implication could be a lack of executive African American leadership available to the black athletes in these institutions and might be an important aspect for you as the NCAA President to consider when addressing inclusivity at the administrative levels of these institutions.

As you are probably aware, PWIs in the NCAA have a relatively balanced ratio of white to black athletes and are disproportionate in the races that fill their administrative positions, yet the number of black athletes to attend these institutions is growing. According to “Significance of Race in College Athletics,” “the interest of black athletes in football to attend a HBCU over a PWI has decreased over the last 40 years due to the amount of television exposure and state of the art facilities athletes receive at PWIs” (Smith 399). This information demonstrates how PWIs have been able to narrow the racial gap in their Division I athletes. However, this also demonstrates how race has implications on commercialism and attractiveness because Predominately White Institutions (PWI) receive better television exposure and facilities than Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) which places them at a disadvantage when recruiting athletes to come to their institution. Therefore, this information shows that race isn’t just having implications on the segregation at the individual and administrative levels in NCAA athletic programs, but furthermore has implications on the commercialism and attractiveness of institutions within the NCAA.

Today the racial demographics of the Division I institutions in the NCAA show that although the percentage of African American athletes has steadily increased, there are still issues of racial segregation at the administrative level and implications of race at the institutional level. These issues are increasingly difficult to address when negative African American stereotypes still exist today. This information may be useful to you when considering the revision of polices on who should be hired for administrative positions and on the advertisement of PWIs and HBCUs.

African American Stereotypes

Numerous stereotypes have been wrongfully representing African American males throughout U.S. history based strictly on the color of their skin, and today is no exception, even for Division I athletes. There are stigmas surrounding the physical attributes of the African American male athlete. In the book, Black Sexual Politics, Patricia Collins states, “the physical strength, aggressiveness, and sexuality thought to reside in Black men’s bodies generate admiration, whereas in others, these qualities garner fear” (153). This statement demonstrates how the same stereotype can be interpreted in both a positive and negative way. These qualities of strength and aggressiveness are what make them such great athletes and admired by many for their achievements in collegiate athletics. However, these same characteristics are the reason why some people see them as “dangerous” because they are allegedly associated with deviant behaviors of violence. The deceptive physical stereotypes that surround black male athletes could possibly portray the NCAA in a negative light because the athletes competing in their program are seen as “dangerous” and “deviant.” This might be important for you to consider as the NCAA president because you want your athletic programs to be portrayed in the most accurate and positive ways possible.

The misconceptions associated with the physical attributes of African American male athletes are historically linked to their intellectual abilities, subsequently leading to further stereotypes. Billy Hawkins describes the historical use of scientific racism, that labels black male athletes as “physically superior” and “intellectually inferior” in his book, The New Plantation (473). Some educational institutions perpetrate this stereotype of black males’ inability to learn by giving their black athletes passing grades even when undeserved (Hawkins 473). This stereotype could possibly lead the athletic departments of institutions in the NCAA to assume that their African American athletes are just “dumb jocks” and place them into non- rigorous majors, just to ensure their athletic eligibility. Black athletes in the NCAA could be at a disadvantage to their white teammates because of this lack of attention to their education and might hinder their career opportunities in the future.