2 Reading Reflection

Reading Reflection Assignment Guidelines[1]

For this assignment, you will carefully read and take notes on a text (an editorial or other reading) that showcases a particular concept, theory, or “big idea” about social identities and communities. You’ll read “like a believer,” trying to see how these ideas function in the world, and apply the text to your life, enabling you not only to show your understanding of yourself and your communities, but also how the text helps you understand something differently. In the process, you will develop a main thesis that clarifies your own and your readers’ understanding of the text and how it helps you connect to something significant about yourself. You may also use a personal anecdote or find examples to clarify the text and your understanding of it.

Your reading reflection will be 1,000-1,200 words long (approximately four double-spaced pages). Your audience will consist of readers such as your instructor and classmates who are interested in how you make significant connections to the reading.

Important: You are not writing about what you agree or disagree with in the text; in other words, you are not taking a stance or making an argument. By “reading like a believer,” you are placing yourself into a mindset in which you open yourself up to what the author is saying and you try to find moments of resonance and common ground, allowing yourself to consider a different perspective.

In other words, you are expressing how you relate to and understand the text, helping your readers to learn more about your thinking and yourself. To do so, you will do a “reflective analysis,” demonstrating how your reading of the text was shaped by your life, your assumptions, and your prior conceptions. In other words, you will not be focused solely on the issue or the content of the text – the “what?” – but also on the “how?” and “why?” In short, you need to explore the text, show that you’ve read it carefully and deeply, and explain how it has impacted you and why you hold a particular understanding of it.

Learning Objectives

• Apply several college-level reading strategies to explore and understand a text

• Summarize a text fairly and accurately to inform an audience

• Develop a main thesis that reflects how a text is personally relevant and significant and how it enables you to show a deeper understanding of yourself and the issue

• Clarify your audience’s understanding by providing analysis, explanation, anecdotes and examples, or other contributions

• Practice writing moves that engage your readers and that show respect towards the issue, the author(s) of the text, and your readers

• Practice attributes and qualities that will make you a more successful college-level writer, including curiosity, perseverance, openness, creativity, and flexibility

Rationale

The Reading Reflection enables you to practice several skills, strategies, objectives and student learning outcomes, and habits of mind that are important to becoming a successful college student and writer. First, you will practice college-level strategies for reading (e.g., note-taking and questioning) and writing (e.g., summarizing and freewriting). You will gain practice in reflecting, which you may need to demonstrate in professional classes and in personal statements for educational and career opportunities. Reflection also helps develop critical thinking skills, your awareness of the self, and your understanding of diversity, which correspond to two of the undergraduate student learning outcomes: Critical Thinking and Diversity. In terms of the ENGL 100 course objectives, this assignment allows you to

- Demonstrate critical thinking and problem solving when analyzing important social and cultural issues.

- Demonstrate competence in academic reading and writing strategies (note-taking, summarizing, and identifying main ideas) and reflect upon your writing process.

- Guide your readers with appropriate organizational strategies and meet expectations of tone and style.

Finally, the Reading Reflection asks you to adopt a mindset that can allow you to practice and demonstrate student qualities and habits of mind that will help make you more successful in your classes and your career. By undergoing this reflective process, you will need to foster your curiosity, creativity, and openness as you make connections between your life and the key concepts or, quite possibly, uncomfortable experiences and ideas that appear in the reading.

You will also need to be persistent and flexible, qualities that will help you as you read and re- read, explore a main thesis, and manage a complicated writing project.

Separating a Reading Reflection from an Argument

To emphasize the differences between a reading reflection and an argumentative or opinionated response – in which you are showing what you agree or disagree with in an author’s editorial – we look at two ways of working with Kim Stagliano’s. “My Three Daughters are Autistic. I Despise Autism Awareness Month.”[2]

Here is a brief summary of this editorial:

In her controversial article “My Three Daughters are Autistic. I Despise Autism Awareness Month,” Kim Stagliano argues that Americans need to stop defining autism as a condition that should be celebrated and even found desirable. Rather, she wants to remind her readers that autism has profound negative effects on people and severely limits their educational and social opportunities.

An Argumentative Response (What You’re NOT Being Asked To Do)

In an argumentative or “opinionated” response, you might decide to disagree vigorously with Stagliano’s points, claiming that Stagliano has a narrow view of what it means to be “normal” and using evidence to show how people with autism make important contributions to society.

Additionally, you could counter her stance on Autism Awareness Month, claiming that these types of events do not celebrate this condition but provide more attention for additional support and treatment. Or, you might consider a combination of agreeing and disagreeing, in which you agree with Stagliano about our need to recognize the challenges of those who experience serious Autism Spectrum Disorder, yet then show how people with autism reflect the variety of possible ways of living and thinking in the world.

While crafting an argument in response to a text is a crucial skill (and one that you’ll practice in ENGL 200), we’re asking that you not respond in this way for this assignment. Instead, we ask that you reflect on the piece in the ways described below.

Reading Reflection (What You ARE Being Asked To Do)

Instead of asking you to show readers your opinions or positions on an issue, reflective reading puts you into a different mindset, one in which you are interested in showing how you relate to a text and to help readers — and yourself — understand why you had those thoughts and feelings and why you understood it in a particular way. In short, you are expressing a personal take on the article and the issue; your readers will learn something about the issue as well as about you.

Returning to Stagliano’s “My Three Daughters are Autistic. I Despise Autism Awareness Month,” you might guide your readers to a personal thesis about how Stagliano’s editorial – especially as she is writing from the perspective of a mother about her three children – makes you feel extremely uncomfortable. You might then try to figure out why you feel so uncomfortable – is it, perhaps, because of assumptions you hold about American motherhood and how mothers are always represented as being 100% supportive of their children? Maybe you’ve heard many examples of parents of children with severe physical and cognitive challenges, who “celebrate” their children and talk about them in terms of “gifts” that have enhanced their lives. So, are you angry with Stagliano for how she performs her role as a mother and for how she talks about her daughters? If so, what does this say about you and your own experiences? What does it say about larger assumptions about motherhood? Is there a way to find sympathy towards Stagliano’s position? Does Stagliano’s position help you understand disability differently?

When you start reflecting on the text in these personal ways and using the reading reflection questions, you will see how you are pursuing different writerly moves and interacting differently with the text and with your readers, developing a deeper understanding of the text and of the assumptions and experiences we, as readers, bring to the text.

The following table summarizes the key differences between argumentative and reflective writing:

| Argumentative Response | Reading Reflection |

|---|---|

| Purpose: You contribute to a controversial issue and hope to persuade your readers. | Purpose: You demonstrate your personal understanding and stake in the text; you show your readers how you relate to the text and how you understand the idea. |

| Audience: Readers who may hold different perspectives on the issue. | Audience: Readers interested in how you personally respond to a text; readers who want to learn more about you and the idea. |

| Typical writing moves: You summarize the text, and then identify an overall claim or position on the issue which you support with reasons and evidence, usually from secondary sources. | Typical writing moves: You summarize the text, and then you focus your readers on an overall reflective thesis or main point, which you then explore through different angles or vectors: your assumptions, your explanation of your thinking processes, your personal experiences and anecdotes, among other possibilities. |

Reading & Writing Moves

Paying Attention to Format

Even before you start reading an article, you can find out a lot about its main ideas and organization by looking at the title, the sub-title, and section headings, if they are available. Before you actually start reading the article, take a look at these elements and make some predictions on important points and concepts that you think you might see.

For example, from the main reading in Chapter 1, Edward Timke’s and William M. O’Barr’s article, you will see the title and the four section headings:

“Representations of Masculinity and Femininity in Advertisements”

- Introduction

- Representations of Masculinity and Femininity in Advertisements from 2006

- Advertisements Ten Years Later: Some Changes, But Not So Many

- A Gender-Fluid Future?

How can this be helpful as you plan your reading? You’ll already know a great deal of the scope and focus of this article: it’s intended to explore representations of gender in advertisements, and you have a sense of historical context: the second section focuses on advertising in 2006 and the third section focuses on 2016; you even have an idea about how Timke and O’Barr characterize the differences between these two periods. Finally, you have another concept, that of gender fluidity, which the authors will explore at the end. Thus, here are the key concepts that the title and headings provide:

- Advertisements

- Femininity

- Gender fluidity

- Masculinity

- Representations

- Historical changes

While the title and headings won’t give the whole “story” of the article, recognizing some of the key ideas before reading can help you read with more focus and direction.

Stock Reading Reflection Questions

As you begin reading (and writing), these following reading questions will place you in the right frame of mind to conduct the reading reflection:

- What is the main point of the text?

- What do you know about the topic? Where does this knowledge come from?

- How does the text reinforce or challenge your assumptions or pre-existing ideas?

- How does the text help you explore the issue or concept or understand it differently?

- How do you relate to the text?

- What is something that you find to be surprising in the text?

- What is still unclear and confusing for you? Why?

- What can you learn about yourself from reading and thinking about this text?

- What connections can you make to your own life experiences outside of class?

You can use these types of questions as you read and take notes; additionally, you may find them useful as you begin to reflect on the reading and generate ideas for your initial drafts.

Active Reading

More likely than not, you’ll be reading the article on a screen – maybe even on the small screen of your cell phone. Although research is still coming to grips with the ramifications of this sudden shift in reading habits, it’s clear that you will want to read actively. By “active reading,” we mean exactly that – commenting and responding by marking up your reading, which could mean finding ways to highlight/underline, using commenting or “sticky note” features on a pdf reader, or devoting a Word file or notebook to collect notes. You may end up using all of these strategies as you actively read.

Although the process for how you are taking notes, annotating, and marking up the text may differ drastically from those of students even ten years ago, your overall goals and note-taking content will remain the same:

- Notes and/or highlighting/underlining that emphasize or summarize the main points (in other words, focus on what the author is saying)

- Notes and/or highlighting/underlining that focus on examples, specifics, and key quotations (consider the important evidence the author is using)

- Questions that help promote your own understanding of the text and the issue

- Comments that link to other readings, concepts, or your personal experiences

- Comments that identify the goals or intentions of the author (in other words, focus on what the author is doing and explore why)

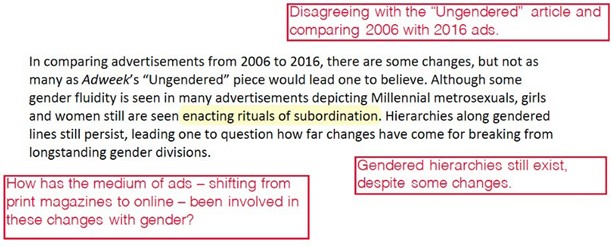

- Here is one brief example, using a paragraph from Edward Timke’s and William M. O’Barr’s “Representations of Masculinity and Femininity in Advertisements”

Here is one brief example, using a paragraph from Edward Timke’s and William M. O’Barr’s “Representations of Masculinity and Femininity in Advertisements”

In these notes, the reader is doing the following:

- Highlighting an especially interesting phrase from the paragraph (“enacting rituals…”)

- Indicating what the authors are doing (“Disagreeing…”)

- Summarizing what the authors are saying (“Gendered hierarchies…”)

- Pointing out a limitation in the reading with a question (“How has the medium..?)

Reading as a Believer

When you read a text, you are asked to demonstrate your openness and flexibility, two key “soft skills” and attributes of a successful writing mindset. When you read “like a believer,” you are being asked to temporarily tune out all of your doubts, concerns, disagreements, and responses. When reading as a believer, you want to understand where the author is coming from and reflect on their assumptions – as well as your own. Peter Elbow explains the mindset of acceptance that is necessary when reading as a believer:

The believing game is the disciplined practice of trying to be as welcoming or accepting as possible to every idea we encounter: not just listening to views different from our own and holding back from arguing with them; not just trying to restate them without bias; but actually trying to believe them. We are using believing as a tool to scrutinize and test. But instead of scrutinizing fashionable or widely accepted ideas for hidden flaws, the believing game asks us to scrutinize unfashionable or even repellent ideas for hidden virtues. Often we cannot see what's good in someone else's idea (or in our own!) till we work at believing it. When an idea goes against current assumptions and beliefs—or if it seems alien, dangerous, or poorly formulated—we often cannot see any merit in it.[3]

What Elbow is asking you to do is to delay the gut reactions you may be experiencing as you read the text: oftentimes, these negative gut reactions may come from an emotional source or from a feeling that you – or a community with which you identify – are being unfairly scrutinized or categorized. Though you may want to note down some of those emotional gut reactions, you also want to show your ability to listen to alternative perspectives and try to understand those from communities beyond yours. To be clear, that does not mean you are being asked to accept these ideas; instead, you are being asked to better understand what these ideas are, where they come from, and how they function for those who hold them.

Exploring Key Concepts & Quotations

One useful strategy to explore ideas is to find a few key concepts or fruitful quotations from the reading. Look for terms that appear in the title or in headings and that are repeated by the author. By “key concepts,” we mean the vocabulary of our social and cultural world that you may have already encountered.

For the quotations, find those that you found “stuck” with you – that is, they were significant and/or helped you understand the main message of the reading.

For example, from Rebecca Carroll’s, “As a Black Woman Raised by White Parents, I Have Some Advice for Potential Adopters,” here are some key concepts:

- transracial adoptions

- systemic racism

- internalization

- stereotyping

Here is an informal freewriting moment from a writer who made personal connections to the concept of “transracial adoptions” and started to question their assumptions; this initial writing will then lead, after some revision, to the major thesis that they present in the Reading Reflection Example.

I’ve had conversations about transracial adoptions, even down to whether it is more acceptable for white parents to adopt African-American children rather than Asian children, as black children will still be able to recognize themselves in other black people and finds ways to express their cultural connections, whereas the Asian children will be separated geographically, culturally, and linguistically. They will be completely separated. Yet, having just thought this, I also have to take stock of my assumptions: in this case, the expectation is that it will be white parents who are the norm, who will be making decisions about the racial or cultural identities of the children they will be adopting.

From the same text, readers may find these two following quotations to be memorable and worthy of spending some more time on:

“Our beauty does not exist because you have given it to us.”

“Your naivete may be legitimate, but if you legitimately don’t understand how systemic racism works, or the ways in which it will target your child specifically and often, then maybe you shouldn’t adopt a Black child. And I mean that in the kindest way possible.”

What could you get out of these quotations? Where could they lead you when you start to consider your own reflection? How could you possibly incorporate these direct quotations in your own draft? Here are two examples of freewrites based on these quotations:

- Carroll is getting at something of the “arrogance” of the relationship between white parents and the children they adopt who may not share their same race or background; these parents may possess unconsciousness biases about race and the superiority of their own position; Carrol is making a statement that the adopted child’s beauty and worth stands for itself – it’s not a value that is bestowed upon them.

- By “kindest way possible,” we get a glimpse into Carroll’s world – here, she is talking directly to her own parents or to those who are extremely similar, and expressing this mixture of love and of teaching; she is showing those painful moments in which the child needs to become the teacher and bring up important issues, such as systemic racism, that they may not have to face but that their students will have to confront (not to mention the fact that the entire situation of white adopting parents is itself an example of systemic racism).

Generating Ideas with Class or Discussion Board Talk

Similar to discovering a thesis by freewriting, talking with others can also help you develop your ideas. That’s why, whether in class or as a part of online discussion boards or activities, your instructor will allow you some time to talk through your ideas with other students who are working and reflecting on the same reading. Use these opportunities to clarify your understanding of the reading and to come to grips with this sophisticated type of writing.

Figure out how your classmates have interpreted the assignment and how they are attempting to relate and make personal the reading. Share your ideas and learn from this productive writing community. If you are participating in an online conversation, remember to go back to the discussion after the due date in order to read what was posted after you completed the assignment and gain some additional insights from your classmates. Make sure, too, that you look for your instructor’s comments on the posts.

Summarizing

Summarizing is going to be an important part of the writing that you do at the college level, in particular when you are asked to find secondary research sources and report them fairly and accurately. Summarizing is also related directly to your active reading and notetaking methods, as you are trying to come to grips with what the author is saying: What are their main points? What are the author’s goals?

For your Reading Reflection, you want to represent the text for your readers and satisfy them enough that they do not need to turn to the original source that you are reflecting on. To do this, you must make sure that your summary is

- Comprehensive (it represents the key ideas from the full reading)

- Concise (it is manageable and accessible for your readers)

- Fair (it demonstrates that you can “read as a believer” and report the reading to your readers in a balanced and objective fashion)

- Accurate (it conveys the main ideas that best represent the intentions of the author)

According to Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein[4], when it comes to accuracy, you’ll want to watch out for the “closest cliché syndrome,” when you place an author’s main point into a more typical or simplistic frame that you are already familiar with. For example, when summarizing Terry Tempest Williams’s environmental editorial, “Will Our National Parks Survive the Next 100 Years?” a writer placed the author’s issue into the debate about global warming and climate change, because Williams referred to the “political temperature in Washington”; yet, Williams was making a point about the conflicts between politicians and never said a thing about global warming. In this case, the writer of the summary was using the “closest cliché,” placing this editorial in an argument about climate change because that is the common expectation of environmental writing. Similarly, sometimes when reading about a potentially controversial issue, readers will distill complicated arguments in unfair and clichéd ways. For example, (mis)summarizing Stagliano as arguing that people with disabilities aren’t as worthy as those without disabilities, or acting as if Carroll is arguing that white people should never adopt non-white children. This is not what either author is actually arguing.

To avoid problems such as “the closest cliché” and other forms of misrepresenting texts, here are some best practices for writing summaries:

- Identify the author and the text that you are summarizing in the first line of your summary: In Rebecca Carroll’s Washington Post editorial, “As a Black Woman Raised by White Parents, I Have Some Advice for Potential Adopters,” …

- Focus your readers immediately on the overall main point of the reading: In this editorial, Carroll argues that white parents who adopt African-American children need to become more aware of systemic racism and their responsibilities for raising their children in ethical and sensitive ways.

- Organize the summary hierarchically. Do not organize according to the paragraph-by-paragraph organization of the reading. Rather than following the chronological organization of the original text (e.g., “First, she says this, then she says that…”), begin with the most important points of the original text, providing any supporting points or evidence necessary for the reader to fully understand it.

- Never refer to an author by their first name alone. The first time you refer to an author, use their full name. After that, use just their last name.

- Write in the present tense and use active verbs to show what the writer is saying and doing:

- Carroll acknowledges ...

- Carroll points out that…

- Carroll argues that…

- Carroll informs white parents that…

- Carroll contends ...

- Carroll uses her personal experience to…

Activity: Evaluating Summaries

Take a look at these two following summaries of Sarah Garland’s “When Class Became More Important to a Child’s Education than Race.” In the first draft, identify the concerns that readers will have, based on the best practices for writing summaries. Then, in the revised draft, list the changes that the writer has made. In what ways is the revised draft now more comprehensive, concise, fair, and accurate?

First Draft of Summary (179 words):

One thing that I found very interesting in Sarah Garland’s article was when she made comparisons of two families, the Klaitmans and the Lynches; by making these comparisons, she was able to show how social class in the United States is relative to the region or city where you live. In fact, the Klaitmans, who have a great deal of money to bestow upon their children, claim that they are “’middle-class New Yorker[s]” but “’upper-class anywhere else’” (131). Something that didn’t sit as well with me, though, was that Sarah had an obvious agenda when it came to chartered schools. Of course, chartered schools may have some problems, but why doesn’t she consider them to be a viable option at solving the problem with inequality and poverty, especially as she indicates that chartered schools enable poor students to succeed (134). In conclusion, Sarah’s article is an important one because of the fact that it argues that race is no longer important in deciding upon a child’s future; instead, “how much income their parents earn is more and more influential.”

Revised Summary (162 words):

In “When Class Became More Important to a Child’s Education than Race,” Sarah Garland shows that increasing inequality in the United States leads to a larger gap in educational outcomes between highly affluent families and those from middle-class or poorer families; in fact, social class, according to Garland, is a better indicator for future economic and educational success now than race. Garland uses statistics from several research studies to demonstrate how the achievement gap and social inequality have increased over the past fifty years. Additionally, she uses anecdotes from two representative families to show how wealthier families can provide many more educational resources for their children and connect themselves to a social network about parenting. Garland lists several policy recommendations to offset educational inequalities and provide poorer families with more spending money. She also briefly touches upon other education-based solutions, including charter schools, though she reports that the evidence is mixed regarding the degree to which they can reduce the achievement gap.

Discovering a Thesis

One key difference with working on your Reading Reflection is that you may not be completely sure what your main idea – your controlling focus or thesis – is going to be before you start writing. In more simplistic writing contexts, especially those in timed testing formats, you need to immediately come up with a thesis and several sub-points. Look at this following example, one for which you would need to generate a main idea within seconds:

Medieval Asian History (50 points; 20-minuted timed essay)

Question: Although the “Great Man” theories of history are oftentimes questioned, focus on the contributions of one important military leader, Chinggis Khan, and explain at least two important contributions he had on Europe and the rest of the world.

Student’s main thesis: In the thirteenth century, Chinggis Khan’s influence on Europe was immense. First of all, the massive empire that he founded provided a lot of commercial and intellectual exchanges between the West and the East. Second, the attacks of Chinggis Khan’s son’s armies on eastern Europe helped unite several European Christian elites. Third, the Khan’s zasag, or set of laws, demonstrated to Europeans that other systems of politics were possible.

While this demonstration of your factual knowledge is important in many contexts, your Reading Reflection is going to allow for more time and consideration, in which you should begin to freewrite and draft, a process which will then allow you to discover what your ideas are. In short, you should practice using writing as a form of thinking, a strategy to come up with and develop your ideas and your main point. By going through this process of discovering a thesis, you are again practicing some of the “soft skills” that are required for reflective writing: you are showing your flexibility and curiosity and your ability to think through complicated ideas rather than quickly jumping to a conclusion.

Exploring Significance

Significance is one of the most important aspects of informative and expressive writing. Significance consists of those moments when you acknowledge why your main point and your reflection is important, both to yourself and to your readers. When you ask yourself questions such as “So what?,” “Who cares?,” “What contribution did you make?,” or “What is at stake?,” you are telling your readers why your reflective contribution is significant.

Without making clear your significance, your readers may not understand why your response and reflection on the text are important for them (or others) to read and understand.

Typically, when we consider significance, we can write about it in three ways:

- Significance for your culture and society: How might your reflection contribute to how your readers understand this text and the larger issue it addresses?

- Significance for the academic field or larger public conversation: How might your reflection contribute to the academic conversations in which the reading and your reflection are situated? What new insights or ways of looking at the world can be useful in future discussions?

- Significance for yourself: Why was this reflection important for your own learning and your own development, as a student, thinker, person, and writer? What did you get out of this type of reading and writing?

Although you can articulate significance in several places in your reading reflection, you may find the conclusion as a particularly useful place; your conclusion is a good place to emphasize these final points that you want to stick with your readers and can help you move beyond simply restating your ideas.

Organization

Unlike a five-paragraph theme, a timed essay exam, or other “closed-form” types of writing, your readers will not have stringent expectations for what to expect in the organizational strategy of your Reading Reflection. You therefore have many options as you guide your readers through your reflection, interest them, summarize the reading for them, identify your own reflective thesis, and explore your understanding and the significance of what you are doing.

Below, you’ll see a template that can get you started, but while you likely need to include all of the points below, many of them can be arranged in a different order, depending on how you want to interact with your own readers and engage them. In other words, while your organization needs to be clear and guide readers through your draft, there is no one right way to organize the Reading Reflection.

Organizational Template

- Focus your readers with a specific title (revise your title as you write, as you want to make sure it reveals your overall reflective point, which can change throughout the drafting process)

- Introduce readers to the overall issue (e.g., cross-racial adoption, the representation of women’s bodies in sports); avoid overly broad and general “Since the beginning of time” or “the dictionary defines gender as” introductions

- Forecast to your readers what you are going to do in your reflection

- Summarize the reading briefly, but usefully for your readers; the summary should be strong enough to situate readers who have not already read the original text, but should not take up too much of the draft

- Identify an overall main reflective point or thesis that focuses your reader on your specific reflective viewpoint

- Develop the main thesis with sub-points, which further allow your readers to see how you are relating to the article and issue, understanding it, and grappling with its complexity and challenges, and are changed by the ideas in the original reading

- Clarify and further develop your main reflective point by contributing a personal experience, additional examples, or a secondary (research) source that illustrates how and why you make sense of the ideas in the way you do

- Conclude, perhaps by highlighting the significance of the reading and your reflection on your own thinking and the ways in which you view the world

Paragraph-Level Organization

Although the broad level of organization is important, when you consider the different sections of your Reading Reflection, you can also focus on a more specific level of organization – the paragraph itself.

Within your body paragraphs, you have many decisions and possibilities, yet here are three ways to make sure you are guiding your readers:

- Using Topic Sentences. Early on in a body paragraph, provide your readers with a statement that reflects the one main idea of your paragraph.

- Distinguishing main points from sub-points, examples, and explanation. Use transitional phrases and readerly cues to signal to your readers what to expect; a simple “For example” or “therefore” can be a powerful way to reach out to your readers.

- Introducing paraphrasing or direct quotations. If you are using paraphrases or direct quotations from secondary research sources, guide your readers by using attributive tags (“According to”) to introduce these moments. Make sure you then explain the source material in your own words and how it connects to your overall reflection.

Activity: Revising Paragraph-Level Organization

Take a look at the following two examples, the first of which many readers may find difficult to read because of its internal paragraph organization. Ask yourself: Where do you find yourself getting lost? What is the main focus, point, or purpose of this paragraph?

Then, read the second example and list the revision moves that you see. What has the writer done to enhance their organization? What are specific examples of the internal-paragraph organizational strategies? These paragraphs relate back to Rebecca Carroll’s “As a Black Woman Raised by White Parents, I Have Some Advice for Potential Adopters.”

First Draft:

Brian Street is a well-known educational expert, whose research is helpful in figuring out how young people come up with their identities. According to Street, we all have a dominant identity or community that we belong to – that is the family: we feel comfortable in the language and ways of being and acting within this family; this is where we feel “natural.” “Early in life, we all learn a culturally distinctive way of being an ‘everyday person’, that is a non-specialized, non-professional personal” (153).[5] Maybe my own experience growing up in a family where I felt “natural” – one in which I didn’t question my language choices, my appearance, or my culture – makes it more difficult for me to relate to what Carroll is going through in her editorial. What happens when you don’t look like your parents? What happens when your language or dialect doesn’t feel “natural” to you? What happens, in other words, when you do not feel comfortable in your own primary identity – that of your family?

Revised Draft:

While reflecting on Carroll’s editorial, an important realization that I made was my simplistic assumptions about family structures as those places where young people felt comfortable and “natural.” I have never considered the family as a place where young people could feel conflicted and alienated. In our society and in research, this assumption about the family as a comfortable, nurturing space is extremely common. For example, Brian Street, a well-known educational expert, has defined the family as one important place to form the dominant identity and community of people. According to Street, before we become students, members of the public, or professionals, we first learn a basic identity, in which we feel “natural”: “Early in life, we all learn a culturally distinctive way of being an ‘everyday person’, that is a non-specialized, non-professional person” (153). Yet, what happens when we apply Street’s quotation to Carroll’s points? What she is getting at, after all, is a situation in which the family space conflicts in many ways with how the child may identify themselves or feel about themselves. Carroll is defining the family no longer as this “warm and comfortable” space of nurturing, and making it into one that is far more political and ideological.

Tone: Showing Fairness & Objectivity

Oftentimes, when we talk about tone, we are talking about the attitude that you are showing towards the issue, the author, and the reading you are reflecting; toward yourself and your writing; and toward your own readers. In ENGL 100 and in other informative writing situations, you can think about tone in terms of formality: informal writing that shows more intimacy and closeness with your readers and the issue, or more formal writing that shows more distance with your readers.

In a Reading Reflection, tone is also an important way to talk about the ways in which you are interacting with the reading and the impression that you are crafting for your readers. In this rhetorical situation, you want to come across as being fair, balanced, flexible, and somewhat objective. Importantly, you want to demonstrate these qualities even if you find yourself feeling extremely negative towards the author’s points.

Remember your purpose: you are not agreeing or disagreeing with the reading, but, instead, you’re reflecting on your understanding of the issues in the reading. It’s absolutely okay to announce the fact that an editorial makes you feel uncomfortable and disturbs your own assumptions and beliefs. You may even be able to form a main thesis by exploring what is at the heart of this conflict between you and the editorial. However, you still want to come across as fair and objective. You are demonstrating your ability to reflect on an issue without immediately shifting into a rant or an argument.

Here are a few strategies to demonstrate your objective and fair tone:

- In your summary, make sure you’re choosing words that represent the author’s position fairly; pay attention to the verbs that you use to describe what the author is doing. For example, look at these two sentences:

- The author acknowledged that women’s bodies were more sexualized in sports reporting.

- The author whined that women’s bodies were more sexualized in sports reporting.

- There is a large tonal shift between “acknowledged” and “whined”; in the latter, you are making a harsher judgment about the author and what they are doing.

- Think about your pronouns; instead of the traditional “I” and “he or she or they” (for the author you are reflecting on), consider “we” or other ways of bringing you and the author together: “Despite the vast differences in our experiences and our political beliefs, the we both value the importance of financial markets in changing the attitudes of people towards race.”

- Acknowledge your own perspective and check your privilege. If you’re feeling uncomfortable reflecting on a reading from an author whose experiences or social identities are far different from yours, you may want to acknowledge this fact. Tell your readers why you may find it hard to understand another perspective.

- Use phrases that qualify and temper your points; these small tonal cues can be important ways to connect to the emotional lives of your readers:

- Though readers may disagree with me, I…

- One hesitation that I have is…

- I acknowledge the fact that the writer…

- As someone with different political views, it is understandable that…

- Despite our differences, I appreciate the fact that the author…

Style: Using Language That Sticks

“Stickiness” is a writing concept that reflects how memorable your ideas are for your readers. As you are drafting and revising, ask yourself how you can make your words resonate with your readers. How can you make them stick?

One way is by using vivid, concrete language and trying to make your writing more specific and active. In order to do this, you will need to pay more attention to your main nouns and verbs and examine how they are related.[6]

Here are a few recommendations for making your language stick:

- Avoid cliches, because these, by definition, are not going to be concrete and precise; your readers will have heard them before and so they won’t be memorable or meaningful.

- Watch out for overly repetitious starts to your sentences. Be especially vigilant against using too many sentences that start with vague noun-verb phrases as “This is….” “These could…,” or “There is.”

- Try to vary your sentence lengths and structures.

- Avoid relying too much on forms of to be: am, is, are, was, were, will be.

- When you use pronouns, such as “it” and “this,” make sure your readers know what they are referring to.

- Reconsider vague nouns or descriptors, such as “really,” “things,” “huge,” and “very.”

Activity: Revising Sentence Style

Here are several examples that readers will not find particularly “sticky.” Try to diagnose the stylistic concerns and consider some revisions:

That is a huge point that was made by the author!

There are two ways in which I could relate to the discussion about socioeconomic things in Garland’s essay.

Carroll really knocked it out of the park when she mentioned stereotypes and explained how it affected young children.

She made some interesting points.

Example Reading Reflection

This example reflects on Rebecca Carroll’s “As a Black Woman Raised by White Parents, I Have Some Advice for Potential Adopters.” At 1289 words, it can provide a sense of the scope and purpose of this type of reflective writing; it can also serve as a basic formatting guide for your own reflection.

Student’s Name

Instructor’s Name

ENGL 100

Date

Understanding Cross-Racial Adoptions

Rebecca Carroll’s Washington Post editorial, “As a Black Woman Raised by White Parents, I Have Some Advice for Potential Adopters,” opens with a drawing of a black girl holding hands with two white adults, who join a larger group of white people wearing casual clothes and who walk into a field of whiteness. Importantly, the child is looking back – looking right into the eyes of the reader – me. Her face is the only one that I can see.

This drawing does a great deal in quickly conveying the main themes of this editorial – which is extremely painful and courageous, especially as Carroll is focusing readers on the most intimate of relationships – that between the child and parents – and recasting this relationship in terms of race and systemic racism. Although Carroll is not writing a piece advocating that white parents stop adopting black children, she is making several points about how these white parents – and, in this case, the readers are to understand that she is talking directly to her own white parents – are participating in a racist system, although they may not be completely aware of what they are doing. White parents with black adopted children may resort to stereotyping and fetishizing with the ways in which they talk about their children. White parents, moreover, may have little knowledge of black cultural and social leaders and they may have no connections to black cultural forms and to members of the black community. Carroll stipulates that these white parents are practicing racist beliefs and supporting systemic racist structures by hoping that their black adopted children grow up in a “colorblind” – that is, white – world.

Carroll’s editorial is confessional – in this case, she is confessing to her white parents that she recognizes their complicity in racism despite the fact that they were “incredibly loving White parents”; Carroll writes, “[I]f you legitimately don’t understand how systemic racism works, or the ways in which it will target your child specifically and often, then maybe you shouldn’t adopt a Black child. And I mean that in the kindest way possible.” Again, with this last line, Carroll is being extremely personal; in an editorial that is meant to address the issues of transracial adoptions and to speak to white parents, she is doing this work by calling out what her parents have done to her.

As a parent of two children, I tried to imagine myself reading this editorial for the first time as I were Carroll’s primary audience – parents who had adopted African-American children or, for that matter, children who were considerably different than them for race, linguistic, social class, or other reasons. What must these parents be feeling? Hurt? Resentful? Angry? But, also, quite possibly feeling guilty and complicit? Of course, my personal experience is limited when it comes to Carroll’s argument: my children and I never had to question the community and the identity that they were brought up in, although we did want them to realize that their skin color, language, and social class were not universal norms and identities; we dutifully clicked “diversity” as one of the most important qualities when enrolling them into daycare centers. We have several white friends and acquaintances who have adopted or served as foster parents for African-American children, and our neighbors – who could be described as “salt of the earth” Kansans – have created a large, close-knit family by adopting cross-racially.

To my knowledge, they have decidedly not followed any of Carroll’s suggestions, and I would be surprised if they made any cultural accommodations besides bringing their children up with their Catholic views and a strong work ethic. Race, as a concept involved in their family structure, would never have entered their thinking.

As I read Carroll’s editorial, though, I found yet another example of how race, especially in the United States, involves, subsumes, and penetrates the lives of all people. White parental adopters, though, may not be aware of race or may have found ways to justify what they have done: instead of thinking in term of race, for example, they could point to their liberal good intentions or, as in the case of my neighbors, think in terms of religious faith. And, from Nicholas Zill’s online article, “The Changing Face of Adoption in the United States,” we can understand who most of these white adopters are: they are older and more financially secure than biological white parents. Yet, here in my realization, one in which social class and race become intersected, is where this most intimate of relationships – that of the family – becomes submerged with race. I started to play this though experiment: could I imagine a black couple adopting a white child? Though I am sure that this has happened, I’ve never heard of it before personally and never seen this type of family represented in popular media. Instead, this type of family creates a cultural dissonance because of the fact that it is so hard to imagine. But why? Where is this dissonance coming from?

This hard-to-imagine quality may point to systemic racism, in terms of a complex range of factors, such as economic factors (there are systemic reasons for why white couples will have more financial resources than those of black couples), institutional (there may be assumptions and expectations from adoption agencies regarding what types of people constitute “good” parents, and cultural (there are few representations in popular culture to allow us to make sense of these types of families). Carroll addresses systemic racism when she reminds white parents that the “beauty” and existential significance of their adopted black children do not stem from the white parents themselves; they, according to Carroll, do not bring the beauty and the worth to their children – that beauty and worth already pre-exists within them.

According to Zill, white potential adopters may be paying attention to these conversations about race and systemic racism: since 1999, white parents are adopting far fewer African- American children in favor of adopting children with Asian ethnicities.

A final way for me to make personal meaning out of Carroll’s editorial is to recognize the power that Carroll endows upon parents. As far as Carroll is concerned, parents have the power to bestow identities, dispositions, attitudes, and ideas about self worth – and they can create all of this magical identity work through the ways they characterize their children in their language and informal conversations; the example that Carroll uses is “spitfire,” which, when labelling a young black woman, may conjure up stereotypes about “angry black women.” Carroll has extremely high expectations for the linguistic and ideological consciousness of parents, and maybe that’s her point: if you, as a white adopter of a black child, cannot serve this important role as a parent “naturally” – that is, you cannot fluently bring your children up in a diverse and multi-racial community – then you should reconsider becoming a parent in the first place. The risks are too high. Of course, Carroll may hold too much faith in the power of parents, who cannot possibly control the rich alchemy of biological, social, and cultural factors that influence their children’s identities, interests, and influences.

After all, hasn’t Carroll demonstrated the lack of power of parents in the overall identity formation of their children? Carroll has been able to write this highly intimate criticism of her own white parents because of her “adoption” of new communities, concepts, and ways of speaking and writing.

Works Cited

Carroll, Rebecca. “As a Black Woman Raised by White parents, I Have Some Advice for Potential Adopters.” The Washington Post, April 5, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/04/05/black-woman-raised-by-white- parents-advice-potential-adopters/.

Zill, Nicholas. “The Changing Face of Adoption in the United States.” Institute for Family Studies. August 8, 2017. https://ifstudies.org/blog/the-changing-face-of-adoption-in-the-united- states.

Performance level of a Reading Reflection 1

| Expos Criteria | Your Reading Reflection Exceeds the Assignment Objectives |

|---|---|

| Purpose/Focus | •Accurately and fairly summarizes the reading in a way that is meaningful for readers. •Articulates an interesting / complex reflective thesis that demonstrates your ability to understand, reflect on, and relate to the reading. |

| Development | •Fully develops your main ideas and satisfies your readers; deftly uses sub-points, explanations, secondary research, examples, personal anecdotes, and other forms of support. |

| Organization | •Organizes your ideas in ways that are helpful and clear for your readers; your readers can easily differentiate your main points from your support within paragraphs; you guide your readers throughout the reflection (e.g., by using transitions and readerly cues) and through each paragraph by clearly marking the connections between sentences and ideas. |

| Tone/Style | •Tone shows your openness, objectivity, fairness, and flexibility; style (word choice, sentence structure, sentence variation) engages the reader and help make your ideas stick. |

| Editing/Proofreading | • Demonstrates careful and consistent attention to formatting, proofreading, and accuracy. |

Performance Level of a Reading Reflection 2

| Expos Criteria | Your Reading Reflection Meets the Assignment Objectives |

|---|---|

| Purpose/Focus | •Summarizes the basic gist of the reading, though not always comprehensively or accurately; summary may not match purpose or may not be totally fair. • Includes a reflective thesis, but it may be too general and may not remain consistent in its reflective purpose; at times, you may be responding to the issue, not reflecting on it. |

| Development | •Develops your main ideas, but readers may expect more reflection and connections to other ideas, examples, personal anecdotes, and secondary sources. |

| Organization | •Organizes your ideas but does so minimally and generically; readers may not always be able to differentiate main ideas from support. |

| Tone/Style | •Shows an attempt at fairness, though tone may not always be consistent or appropriate. Style does not always increase ideas’ “stickiness” for a reader. |

| Editing/Proofreading | •Demonstrates some attention to formatting and accuracy, though not consistently; readers may have to hesitate at times due to minor errors, although they do not deeply detract from the reader’s understanding of your ideas. |

Performance Level of a Reading Reflection 3

| Expos Criteria | Your Reading Does Not Meet the Assignment Objectives |

|---|---|

| Purpose/Focus | • Fails to summarize the reading accurately and fairly; summary is not useful for readers and does not meet purposes of your reflection. •Fails to include a thesis statement, or the main point may not meet the reflective purpose and may resemble a “rant” or an argument showing your opinions about the issue of the reading. |

| Development | •Fails to develop the reflection through the use of explanation, examples, secondary research, and personal anecdotes; your discussion is not helpful and meaningful for your readers. |

| Organization | •Fails to organize the reflection adequately for readers; readers will not be able to differentiate main ideas from supporting points; might not use paragraphing, transitions, and other strategies to guide readers. |

| Tone/Style | •Fails to demonstrate balance and fairness; you may come across as overly glowing or angry and disrespectful. |

| Editing/Proofreading | •Fails to show care and attention to formatting and accuracy; readers will struggle to make meaning out of your writing. |

Workshop Writers: After reading through these different descriptions of the criteria and these three different levels of reading reflection performances, pose for yourself and your workshop partners 2-3 primary questions or concerns that you have with how you have met the purpose/focus, development, organizational, and tonal qualities of the reading reflection.

Workshop Readers: Read your workshop partners’ questions or concerns and keep in mind these overall criteria. While you are reading, comment in the margins of your partners’ drafts, making sure to do the following:

- Include at least two comments, positive notes, revision suggestions, or questions that ask your partners to consider their purpose/focus; after these types of comments, write “purpose/focus” in parentheses.

- Include at least two comments, positive notes, revision suggestions, or questions that ask your partners to consider their development; after these types of comments, write “development” in parentheses.

- Include at least one comment, positive note, revision suggestion, or question that asks your partners to consider their organization; after these types of comments, write “organization” in parentheses.

- Include at least one comment, positive note, revision suggestion, or question that asks your partners to consider their tone/style; after these types of comments, write “tone/style” in parentheses.

Student Examples

“Get Up, Stand Up -- Stand Up For Your Life”

Taylir Charest

Taylir Charest wrote this Reading Reflection in Spencer Young’s ENGL 100. Charest wrote her reflection on Chet Ellis’s “The Sound of Silence.”

We all face small, everyday transgressions by others in one way or another. Most people endure comments or jokes about their race, age, weight, or gender each day. Do we perpetuate the discrimination because we do not initiate a change by standing up against those everyday transgressions? Chet Ellis believes we do.

In "The Sound of Silence" by Chet Ellis, he writes about his middle- and high-school experience where he learns that by not speaking out against racial microaggressions early, he lets offenders think what they are doing and saying is okay, and the microaggressions only get worse. In hindsight, Ellis does not blame himself for being racially targeted, but he does blame himself for not standing up against others. In his hometown of Westport, Connecticut, he was one of the only Black people, leaving him feeling like he stuck out like a sore thumb. In middle school, “I’m blacker than you,” was a remark from his classmates because he had not listened to Lil Wayne’s album that had just dropped. Ellis let it go, which was one of his first mistakes. Not wanting others to feel like he did when people made jokes that offended him, he would smile or simply change the subject. This response made microaggressions worse for him in high school. Freshman year during soccer season, his teammates used to play “get the minority,” where they chased him down, so they could tackle him. These were not the only instances when microaggressions occurred. After doing some research on why it was difficult for him to stand up for himself, Ellis questioned if it was his fault the jokes got so bad, and if he had stood up for himself sooner, would the jokes have stopped? Following this, Ellis took accountability for not speaking out.

Reading this article for the first time, I immediately found myself being able to relate to Ellis and his experiences. This does not mean I understand what it feels like to experience racism. Though I have not experienced racial microaggressions, I parallel his experience with mine being a woman. I will now show three examples of how Ellis’s remarks hit home for me. For instance, when the microaggressions got too much to handle and he did some research on why it was so hard to stand up for himself, he found a meaningful article and quoted it in his paper. It said “For token women, the price of being one of the boys is a willingness to turn, occasionally, against the girls. The token woman, in other words, is required to sell out her own kind.” And Ellis questions, “Had I sold out my own race in an effort to fit in?” A token woman is included in a group to make others believe the group is being fair and inclusive, when this is not really true (“A Token Woman”). Ellis felt some of the same things a token woman does. Though I do not quite feel exactly like a token woman, I can relate to this because I have many friends who are young men, and I am often referred to as “one of the boys” when I am with them. They are who I have always hung around. Being in this situation, sometimes I did find myself selling out my own gender, putting myself and other women down, just to fit in with them.

Another time I found myself relating to Ellis was when he talked about a really bad “joke” that his classmates made, and he only reacted with a smile. Ellis said, “He had offended me to my core, and yet there I was feeling compelled to smile so as to not offend him.” For me, this happens quite often, just as it did to Ellis. If one of the guys is making a joke, I am probably going to laugh at it, no matter how bad it is. I might not laugh at as many things as I used to, but I never wanted to stand up against the joker and make him feel like he was not funny. I always found myself smiling and laughing along because I did not want the boys to feel how I felt. The misogyny that laced their jokes was offensive and got to be too much sometimes. They even recognized their offensiveness at times, but then joked about being really misogynistic with their humor. I wondered if they said some of the same things about me that they said about other girls when I was not around. Trying to be so relatable for them really took a toll on me. This is how I think Ellis felt when he was reacting the same way. He did not want to make someone else feel bad, even though others at his school were making some of the most insensitive jokes I have ever heard. It was continuous acts of misogyny without consequences from me, and continuous acts of racism without consequences from Ellis.

The last example I found myself relating to is when Ellis gave us some background on himself at the beginning of his paper and said, “I covered myself in rags from J. Crew and Vineyard Vines as camouflage, trying to show the people around me that I belonged.” He wore overpriced shirts, in my opinion, just to try and blend in with everyone around him. This action pertains to me, but almost in the opposite way, as I am not the type of young woman to wear “nice” or fancy clothes. You will see me in athletic shorts or leggings and a big T-shirt most days. I like being comfortable and do not like to stand out. When I do dress in something other than my normal, people comment on it, and it makes me uncomfortable. Women have to confine themselves to fit society's standards, while men can wear almost anything they want without being chastised. When women wear anything that shows off their figures, they are automatically sexualized. This is why I wear the clothes that I do. Ellis used brand name clothes as a way to fit in, just as I do with unrevealing clothing.

Overall, “The Sound of Silence” helped me realize that “letting it happen” is not the way to approach things. This essay was influential and relevant for me because it helped me realize that something similar is going on in my life, and it showed me how I can change to make it better. When people are being offensive towards you, actually standing up for yourself can stop these offensive jokes and comments in the future, and it may even get people to stand up with you. I hope this article urges others to see that staying silent is not the solution, whereas speaking up for yourself and others is.

Works Cited

Ellis, Chet. “The Sound of Silence.” 2019 Team Westport Essay Contest. Town of Westport, CT, 2019. https://www.westportct.gov/home/showpublisheddocument?id=18523.

“A Token Woman / Black / Gay, etc. (Phrase).” American English Definition and Synonyms.

Macmillan Dictionary, Macmillan, 2021, www.macmillandictionary.com/us/dictionary/american/a-token-woman-black-gay-etc.

The Desire for a Single Story in an Interconnected World

Connor Aggson

Connor Aggson wrote this Reading Reflection in Phillip Marzluf’s ENGL 100 class. It won second place in the 2022 Expository Writing Program Essay Award Competition.

“It’s us versus them.”

“We’re the good guys.”

“Toe the party line.”

As socio-political beings, we’ve all known thoughts such as these, whether they’ve been implicitly directed towards us or they’ve originated in our own heads. Together, they form a narrative of our own self-righteousness, molding bias and fueling our decisions. This “story,” though arguably helpful to us in primitive settings, becomes detrimental when combined with our world’s ubiquitous connectivity through social media. As such, these biases, these “single stories” we have of others, are now the source of much danger in our contemporary, globally- minded age.

Within “The Danger of a Single Story,” a talk given by writer Chimamanda Adichie, Adichie discusses the importance of understanding people in a multi-faceted, nuanced way. As a middle-class Nigerian woman surrounded by western literature and influences, she became well integrated into a global cultural environment. Western culture, to an extent, became a part of her culture, and defined her early creative identity. Conversely, others' perceptions of her own experiences were comparatively narrower, with some automatically expressing pity under their own universal assumptions of Nigerian life. These assumptions, she points out, are a result of only understanding her by a single story.

Through these experiences, her goal is to express the power of storytelling. Her message is that by understanding a group, community, or country from many stories, people learn the ways in which they are similar, but by focusing on a single story, it makes others appear more different than they really are, and distracts us from finding honest, human common ground. Her early integration with western literature has allowed her to see many westerners in ways she may not have otherwise. Comparatively, as her own statements tell, Nigerian literature is relatively unknown when compared to the power and influence of the West. In this way, she was forced into this integration through a supply shortage, and undoubtedly this forced experience has resulted in her unique perspective later in life. As a writer and philanthropist acting in a globalized world, these experiences, and the philosophy she’s built from them, are instrumental to her unique perspective, and the message she wants to tell.

Reflecting on her experiences, I’ve considered how (or how not) the concept of “a single story” affects the broader modern world. Are we now, as younger people living in a globalizing world, more or less keen on the trappings of a “single story”? How could this be quantified? Nowhere could this question be looked at further than by pointing to the greatest tool for human connection ever invented: the internet.

Being in the age of information has given me a great deal of insight into the ways a “single story” mentality perpetuates. It’s a common sight to see people grapple with the easiest interpretation they can about a topic or group, but why is this? Much of it comes down to the internet’s sheer surplus of stimuli to process. For example, it’s much easier to read a tweet posted by a friend than to compare firsthand accounts of a situation as it unfolds. In essence, the internet makes us hyper-aware of everything going on, but as a consequence, makes it more difficult to focus on what’s in front of us at any given time. Internet politics in particular offer a direct example of this. With so many voices vying for attention and only so much time to look at them, the effects of bias, of “single stories,” is all too easy to come by.

As a middle-class, white Kansan citizen, statistics would bet that I, and those I’d meet, would be conservatively minded. But as a citizen of the internet, the “single stories” that define political dogma come at all angles. In this way, the boundaries of my geography fell apart, replaced instead by the boundaries of diverse ideology, values, and discourse. As someone who has explored many nooks of the political spectrum, it’s not as if this resulted for me in some kind of ideological renaissance. Each portion of politics I delved into was all consuming for the time I was a part of it. As a twelve-year-old, I was incredibly liberal, dipping my toes into atheistic circles and the contemporary, gamer-gate inspired wave of feminism from figures such as Laci Green and Anita Sarkeesian. During the late “red wave” of 2016, I rescinded much of this and discovered niche conservative views. Since then, I’ve been in and out of various political circles, and even now, I don’t know where I stand. In each of these cases, however, the degree to which they dominated my thinking was incredible. The internet let me explore these viewpoints as much as I’d liked, and I could always find a take on current events or a review of history fit to my current leanings. Pulling briefly from Adiche, her described variables of power and geography with regards to national biases, extended to the internet, show a new dimension of deeply niche ideological bias.

In spite of my experience, one which others have had analogously, there is a general perception that the internet has created a revolutionary public square that allows ideas to flow like metaphorical water in a riverbed of fiber-optics. Because of it, these ideas could be hyper- evolved, allowing humanity to reach collective conclusions with more unity and swiftness than at any other point in human history. But in spite of the space-time compression offered to us, the river which comprises internet ideology isn’t a flow of water. The water is an illusion, covering up the stubborn, weathered bed of pebbles at the bottom. Each pebble represents a niche within an ideological niche, a piece broken off by water erosion from what must once have been a monolithic partisan rock.

On the internet, there is less national unity, there is less partisan unity, there is even less political unity. Every sect has their story, and every story has its omissions. This is the effect of the internet on our “single stories”; its implementation allows us to focus on our in-group biases through the overabundance of information. It is the opposite of Adichie’s situation: whereas she had the opportunity to humanize western society because of an underabundance of information, this surplus puts a buffet in front of us, asking us to pick and choose what we want to see. One can see how when these factors apply to politics, they can create many single stories, bringing the dangers that come along with them.

The “pick and choose” attitude of the internet is another factor which I can speak to personally. The internet has allowed me to meet people I couldn’t hope to without it and explore ideologies that I never would’ve thought of. But statistically, the people I’ve met and regularly talk to tend to share my values, culture, race, and even geographical region. Out of the billions of people using the internet, these kinds of consolidations would seem statistically impossible, but knowing this of my own experience, and knowing this applies to the majority of people, it truly speaks to the power of our in-group biases and social influences.

Adichie, by exploring the dangers of a single story, powerfully quantifies an important reality that we face as humans. We are at an important crossroads in the face of the internet, globalization, and how we handle our own “single story” biases. How do we leverage the internet to break down these barriers rather than reinforce them? Adichie’s solution, as it applies to the single stories of her country, is to publish Nigerian voices. Could this apply to the digital realm? How could it be adapted? It’s hard to say. The danger of a single story is one we need to be aware of wherever we go. In dealing with this reality, we could take a page from Adichie and be aware of how it impacts our lives, recognizing when and how we fall into its trappings.

Work Cited

Adichie, Chimamanda. “The Danger of a Single Story.” TED, July 2009. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story ?language=en. Accessed 3 Oct. 2021.

Reflection: The Effects of Trying to be “Normal”

Drew Bittel

Drew Bittel wrote this reading reflection in Cecilia Pick Gomez’s ENGL 100 class.

Society has created a standard of what it means to be normal, and many people worldwide are excluded from this standard. Typically, it is those with mental disabilities. The article, “At Risk in the Culture of ‘Normal’” by Jonathan Mooney, calls for a stop to this discrimination and goes into depth on how the connotations related to “normality” and the pressure to become “normal” negatively affect the mental health of those with disabilities. Disabled individuals are

constantly pushed to fit in with society but can do nothing about it because they are different from others. I can personally relate to this topic from witnessing how one of my family members, who had disabilities, was treated by his peers, and I can use this example to explain why this identification of “abnormal” versus “normal” must be put to a hold in order to create a more positive outlook on society and create fairness between people. Instead of trying to force similarities in society, we should strive for individuality and be proud of our differences.

In the article, Jonathan Mooney argues that society must stop treating people with disabilities poorly and learn how to support and be appreciative of all people despite their differences. To support this claim, Mooney uses personal stories from his childhood that illustrate the mistreatment he received for his disabilities as well as many statistics that display how people with disabilities are discriminated against and how this discrimination affects their well-being. Mooney’s overall main purpose is to advocate for a change in cultural mindsets that view “normal people” as superior to disabled individuals and to place importance on the fact that being different is not a negative identification. This article points out many societal flaws that have demeaned and harmed people with disabilities by making them feel like they are not of the same worth as others and that they need to change their character to match societal standards.

Not many people understand the amount of discrimination that individuals with disabilities must endure. Mooney puts this discrimination into perspective by stating a statistic that reads, “Children with disabilities are three times more likely to be bullied than their non-disabled peers.” This statistic is a startling one for me and makes me feel very emotional because I can relate it to one of my cousins who is currently in high school and has a handful of social and learning disabilities such as dyslexia, dyscalculia, and ADHD. He has been struggling to cope with the scrutiny he has been facing at school, an experience that got so intense at one point that his parents enrolled him in a different school, which was still no help. His parents had asked me to have conversations with him to see if maybe I could help him improve with fitting in. But it was then that I realized the true mental effects that this discrimination has on a disabled individual. What was once a very creative and electric child is now a child who has no interest in doing anything he enjoys out of fear of being judged for his actions. My biggest takeaways from my conversations with him are that he has no idea what he is doing wrong to deserve such harsh treatment and exclusion from his fellow classmates. He stated that it makes him want to give up on his own personality and become a whole different person. It saddens me greatly to watch his progression of becoming more introverted and shy each time his family visits me, and I wish I could see the old him again. Many children worldwide are suffering from the same scenario as my cousin, and this brings awareness that children with disabilities are heavily scrutinized and are given the idea that they must change their own personalities to fit in with the rest of society.

In order to better understand why a social transformation is needed, the harmful effects of this scrutiny and discrimination against disabled individuals must be known. Mooney states that “adults with learning disabilities had 46 percent higher odds of having attempted suicide than their peers without learning problems.” Society has created an imaginary standard for the people of the world to live up to, but it does not acknowledge the effects these standards play for the ones who do not meet its expectations. I can relate to this statement from Mooney through an experience I encountered in my freshman year of high school when another freshman, who had mild autism and was the center of many jokes, took his own life. This tragedy really opened my eyes to the effects of the discrimination people with learning disabilities must face. Though I did not know the kid all that well, I felt the sorrow his family and friends must have felt and was angered that the people who had given the kid a hard time did not feel guilty whatsoever. The fear of my cousin becoming a part of the statistic that Mooney had stated makes me understand the need for a social transformation to respect all people of the world for who they are, no matter their differences. A difference is not something that one should be scrutinized for but is yet something that should be treated just as anyone else in the world. Society has made these people feel the opposite, which results in the failure to meet the standard and the suicide rates of disabled individuals to rise.

To put a hold on the discrimination against people with disabilities, a social transformation that requires inclusion and the embracement of people with differences is needed. Throughout my own high-school experience and from what my cousin has shared with me about his own, it is no doubt that people with differences are discriminated and scrutinized against. I always made the extra effort to treat those with disabilities the same way as I wanted to be treated, but I could never understand why most other people treated them as outcasts. According to Mooney, a social transformation that “requires us to include and to love” is needed. This quote is a very vital piece of advice for society that Mooney is giving us, that to end this discrimination requires us to include all and be appreciative of all. This statement from Mooney really hits me; if the kids at my school had taken this advice, that child wouldn’t have taken his own life in his freshman year. If the kids at my cousin’s school had taken this advice, then he wouldn’t have to suffer this wave of depression and scrutiny that he is currently enduring. This point goes for people all over the world who are being discriminated against for their disabilities. Difference is not something that should be looked down at, but rather something that everyone should appreciate. And the sooner the world learns to include and love all human beings, the sooner everyone will be able to understand and relate to each other.