Reference

7 Teaching with Zines for Engaged Learning

Allison Chomet and Danielle Nista

When designing a lesson plan, especially for an introductory one-shot class, it is almost too obvious to say that the materials the archivist or librarian chooses should be engaging for students to work with. Though Katheryn Matheny described the cookbooks she taught with as “approachable but complex primary sources” and “rich personal and social texts,”[1] her advice to use these types of materials applies broadly to any format in an archival instruction session; having a strong hook helps boost new users’ confidence in handling and analyzing primary sources. We found that zines—handmade noncommercial publications—can be an effective teaching tool because they exemplify the attributes listed above: approachable but complex, personal, and social.

The visually engaging and highly emotive nature of zines encourages students to connect to the creators and readers of zines. In our experience, faculty might be surprised by the format choice, but excited to get to work with something new and perhaps a little unfamiliar. In fact, before teaching with zines, Danielle Nista, Assistant University Archivist at NYU Special Collections, was also unfamiliar with the format, but Allison Chomet, Reference Associate in Special Collections, quickly helped her realize how effective zines are for getting students to focus on care and handling of materials, reading texts critically, and understanding the way special collections materials are described and stored.

In order to understand how to incorporate zines into the classroom, we first need to understand what zines are and how to identify them. As defined by Amy Spencer, author of “DIY: The Rise of Lo-Fi Culture,” “Zines are non-commercial, small-circulation publications which are produced and distributed by their creators.”[2] Zines differ from other similar sources like scrapbooks, diaries, and artists’ books in that they were intended to circulate to prescribed social networks (unlike diaries or scrapbooks), and in that they were most often made as economically as possible, typically using only the most commonly available materials.

Zines have an almost century-long history, but most people got to know the term “zine” in the 1990s with the popularization of the format, which aligned with the ubiquitous availability of the Xerox machine. In this chapter, we will use the term “zine” with this popular understanding in mind, mostly referring to non-commercial, self-made publications during the last decades of the twentieth century. While many now publish zines online, we will primarily be focused on physical, paper-based zines.

Science fiction fanzines are typically cited as the earliest zines, beginning to circulate in the 1930s as fans of the genre looked for new ways to connect. The format bloomed to eventually include comics, and then zines about rock music, leftist politics, coverage of the burgeoning punk movement in the 1970s, and into a wide variety of topics.[3] “Despite their disparity of subject matter, the great majority of zines share many common characteristics that bear examining as a whole—such as their emphasis on autonomy and independence, and their often confrontational relationship with mainstream culture and communication media,” writes Fred Wright in his History and Characteristics of Zines. This general ethos of outsidership is important to highlight, as well as the way zines served as organizing hubs for social networks of like-minded readers and writers.[4]

Zines were typically circulated through the mail or via zine fairs, and were sold at small, selected (usually leftist or specialty) bookstores. Because the zine maker was typically primarily the one to circulate their materials, they had a certain amount of power over who would see or use their work. Eventually, more centralized zine distribution emerged which further entrenched networks and grew readership. Although there was debate among zine makers about the extent to which the primary function of zine creation was building community or expressing one’s own unfiltered thoughts,[5] it is undeniable that communities formed around zines, and zines were created from communities. Because of these ties, authors map “personal networks”[6] that resemble connections via social media that students may be more familiar with. This comfort can be helpful for new archival users because there is a clear entry point that can lead to a better understanding of how to apply archival research skills.

Beyond their circulation patterns, zines also are a way for primary source instructors to include the “unfiltered personal and political voices of people from different backgrounds, countries, and interests,” namely marginalized folks such as “girls and young women, women of colour, working class women, queer and transgender youth.”[7] Students are often interested in finding out more about everyday people[8] (and those who might resemble them within archival collections) so it is critical to include sources that represent non-mainstream voices in teaching. Bringing these stories to the forefront reminds students to think about who is represented in a collection, by whom they are being represented, and how their materials got to the archives in the first place. Zines do not always end up in a special collection because the creator donated them; they end up there because the person who received the zine donated them. This concept of the creator and the donor being different entities can get students thinking about the decisions that were made prior to accessioning and the effect that has more broadly for collecting material.

It is worth noting the complicated sense of belonging some individuals have felt in the broader networks of zine-makers,[9] and some of the implicit and explicit racism, homophobia, and other discriminatory views of some of the communities they were writing for and with. Many commentators have remarked that the Riot Grrrl scene, for example, was made up almost exclusively of white and suburban girls.[10] Zine makers of color formed their own networks for creation and distribution of zines, like the People of Color Zine Project, which assists in raising the profiles and findability of zines by people of color.[11] It is important to stress to your students that just because the zine as a format breaks many barriers, it does not mean that they were created by authors or communities free of the discrimination that they frequently critique.[12]

Methods and Technologies Used to Create Zines

Students will observe that zines have a very distinctive look, so instructors should be aware of the variety of ways zines can be produced and duplicated and how that has changed over time. Zines created before the mid-1980s were typically mimeographed. Mimeographs are a form of stencil duplication powered by a hand-cranked drum. Mimeographs can be any color, but are frequently one color only (multiple colors would have required multiple passes through the machine), and have somewhat simple, line-based designs (it is very hard to fill in black space in a mimeograph, without compromising the integrity of the stencil). Stencils were frequently created on a typewriter, but could have hand-drawn details; it was nearly impossible to recreate a photograph on a mimeograph.[13]

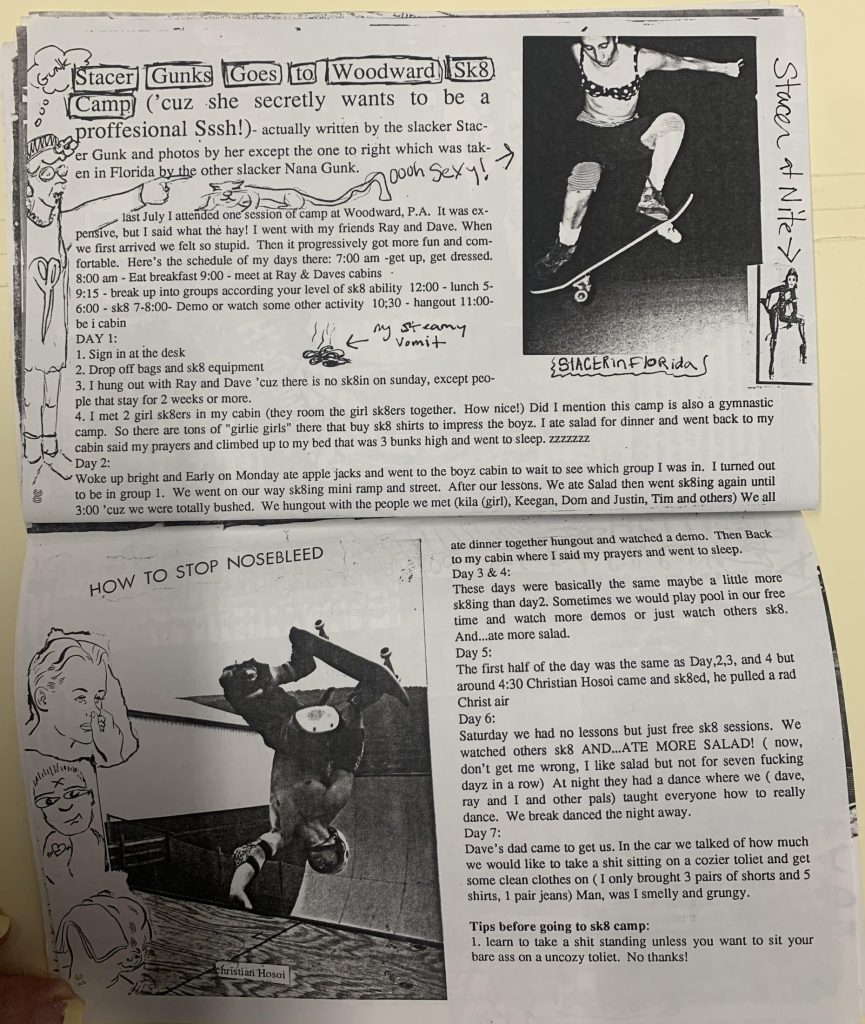

Zines of the later 1980s and 90s were most often created using xerography (commonly called photocopies or xeroxes). Typically, a zine maker would create a multi-layered, multi-media collage of writing, drawing, photos, cut-outs from magazines, stamps, or stickers to make a kind of master copy. The zine maker would then take the master to a copy shop (or to an office or a friend’s office, particularly if copies could be cheaper or free) to use a xerographic machine to run off circulating copies of the original. Typically, this was done in the most time- and money-efficient way possible, which meant that zines were often small in format and printed in grayscale, which cost much less than whole pages and color ink. Zines are often quarto (printer paper folded twice to make 4 smaller sheets) or duo (paper folded once to make two sheets).[14] See Appendix A for images of a zine master, and xerographically reproduced copies of those pages that make up the circulating copy. Note that the master page does not show two pages that are chronological in the circulating copy; this is because zine masters needed to be structured so that the page could be photocopied and then collated into chronological order, and form a book once stacked and folded down the center.

Xerographically reproduced zines are sometimes confused with more “professional” publications (sometimes also called zines) that were created using offset lithography (i.e., a commercial printing process used by newspapers, magazines, and in book publishing). Offset lithography is a more complex process than xerography, and is only done by highly trained professionals in (usually union) shops. Still, some widely circulated zines were made using offset printing once there was enough interest; offset printing, by the 1980s and 90s, was by far the cheapest option to make thousands of copies of any print material.[15]

The Riot Grrrl zines and other punk zines of that time make use of xerography’s capabilities, and frequently re-appropriated images cut out from mainstream magazines or other sources, giving oppressive images from women’s or children’s publications new and ironic contexts. Marking up, annotating, and altering these images was an important part of the political context of the Riot Grrrl and other politically left subcultures.

Importantly, xerography and mimeograph are simple and accessible processes and could be done easily by the zine maker herself. This was a major part of the punk/Riot Grrrl DIY ethos—that these publications could and should be made by members of the scene for themselves, without the kind of oversight, political direction, and potential censorship that would come with reliance on advertising for funding.

Handling and Teaching

The ways in which zines were created, produced, and circulated offers many learning opportunities for students in terms of handling material, analyzing the source in front of them, and understanding archives in general. For the most part, handling the distributed copies of zines is relatively straightforward. You will encounter zines with a variety of “bindings,” such as glue, staples, or pages folded together.

For optimal preservation, most zines should be viewed in book cradles that support their binding, even if they are staple-bound. Preventing students or other users from pressing on pages or bending them to make them lie flat is more easily accomplished when the zine is presented in a book cradle. Students may think that because these zines look like other photocopied material they have encountered outside the archives they are less worthy of preventative handling and care, so it is important to encourage careful habits when interacting with zines. Remind students that their choices about how they handle the objects impact future users. Physically examining the zines is also a great moment to start the conversation about zine networks and what the physical characteristics of the object tell us about its original use and distribution, particularly if the receiver’s or creator’s address is written on the zine.

If your institution has collected material from zine makers, these collections may include master copies of zines. These are often in collage format and quite delicate, held together with glue, tape, or other adhesive material that is likely aging and failing. Depending on the institution and available resources, these master copies may or may not be housed in mylar. Any decision about serving these materials to students should depend on the condition of the item, but if you do decide to bring them to a class, remind students that they should be aware of loose elements and that they should always use both hands to turn pages slowly. (Housing each page of a collaged zine master in mylar is helpful if you have the resources to do so.) If there is a distribution copy of the zine available, comparing and contrasting the physical elements and ways they encounter the object can enrich students’ understanding of the zine-making process. Again, see Appendix A for images that illustrate the differences between master copies and circulating copies.

Regardless of whether students are using master copies or distributed copies, students will start to notice the visual cues and use of imagery and text in the zine. Encourage them to note down common themes and ask them if they can discern the creator’s voice, opinions, or thoughts not only from the content but also in the formatting. The goal is to encourage students to understand more about biases, perspectives, and choices in the creation of any document by grounding that discussion in zines since these questions are more obviously answered by this format.

There are a number of ways to discuss how to find zines, depending on how they are described in a repository. Both authors worked extensively with the Riot Grrrl Collection in the Fales Library at NYU Special Collections, and taught with that material. The zines in the Riot Grrrl collections are organized archivally, according to the person who donated them. This means most of the zines in a given collection were not created by the donor (though there are notable exceptions where donors gave both zines they created and zines they received). The effect of this method of organization is that students can more easily see the network of zine sharing among members of the Riot Grrrl community, but it does make it challenging for them to search topically, thematically, or even by creator. It is also by no means a comprehensive look at zines from a particular time or place since the curation decisions were made long before the materials came to the library.

As a contrasting example, the Barnard Zine Library catalogs the zines in its collection which allows researchers to browse zines by subject. Where possible, librarian Jenna Freedman collects two copies of a zine: one goes into a folder in an archival box, and one is put onto zig zag shelving with necessary supports in the circulating collection. This organization addresses the common ways researchers search for zines, including “wanting to find zines by identities, topics, genres, styles (e.g., risograph zines), or graphics (like zines that have a typewriter on the cover).”[16] While each catalog record does track the provenance of the zine, the focus shifts away from the means of acquisition.

Neither method of organization is preferable over the other; the main point is that the librarian or archivist needs to communicate the differences to students in a class. The subtleties between archival description and bibliographic cataloging may be obvious to someone working in the field, but to students who may be encountering special collections for the first time, there can be some confusion about how to search for material, depending on the nature of their question. Being mindful of this potential barrier to access gives the instructor a chance to intentionally incorporate search strategies into their lesson plan.

Depending on how zines are organized in a larger collection, you might follow different approaches to helping students contextualize the selection you have provided for the class. If you have pulled zines from a collection of personal papers, it is a great idea to share the overall context of how they are a part of a larger archival collection. You can start to introduce the ideas of a finding aid and archival description to students through this concrete example. If you have pulled zines that are part of a bibliographic collection, show the relevant catalog records and catalog search functions to locate this and related material.

Bibliographic and archival description can be complicated for a new user, but having the physical zine paired with the description underscores that description maps to a physical item. It also allows students the opportunity to ask questions about description and discovery. In working with and analyzing the zines, students often comment on their own interests in zines and ask how they can find more. Using this moment to talk to students about how your specific archives are organized and how that is the product of a series of decisions allows them to feel like they can be creative with their searching in order to find what they are looking for. Teaching with zines is an opportunity to expose students to the invisible labor of cataloging and description in a hands-on environment. They can come to conclusions about the nuances of this work themselves and therefore be more empathetic and effective researchers.

Conclusion

Zines are a rich teaching tool since they can address a variety of learning outcomes for an archival instruction session, including care and handling, primary source analysis, and archival and bibliographic arrangement and description. These broad concepts can be intimidating to students at first, but by using a document type that captures students’ attention from the start, archivists and librarians can lower the barrier to learning. Each time we have taught with zines, students leave the class energized and talking about returning to do more research. It is clear that they connect with the zines on some level and feel like the archives and special collections are places that will welcome their creative exploration.

Appendix

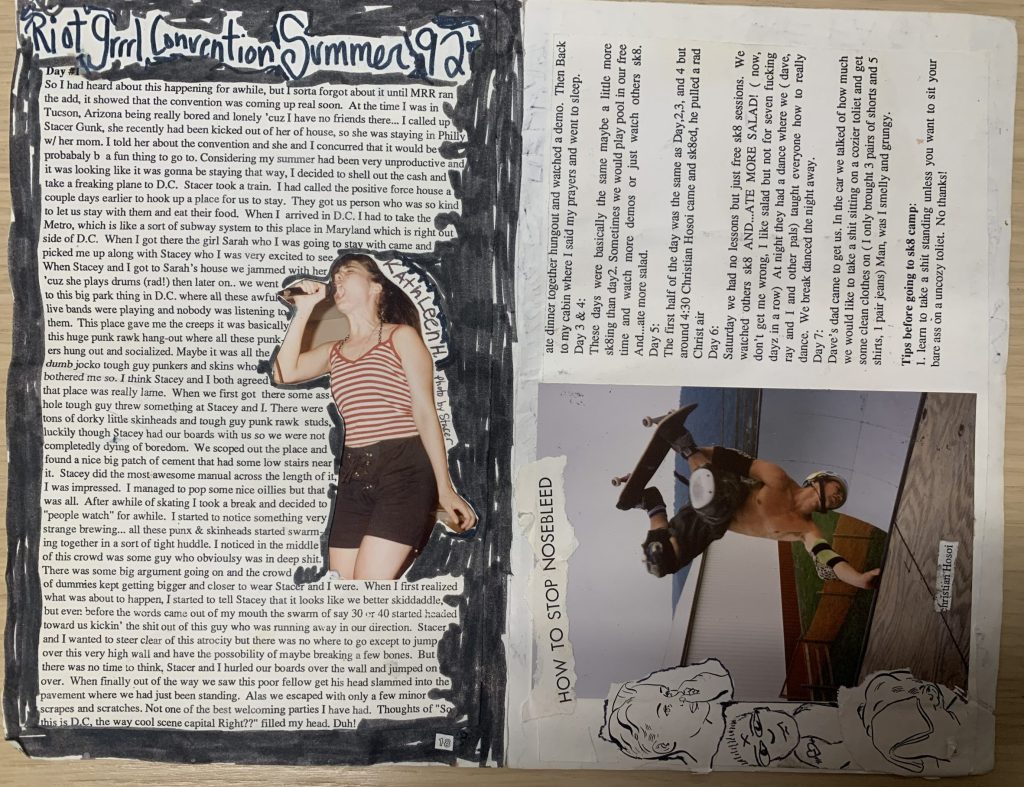

Image 1: Master copy of GUNK #4 created by Ramdasha Bikceem.

If we were teaching with this item, we would ask students to comment on what they notice, guiding them towards bringing up features like the collage techniques, handwriting, text, drawings, and other visual elements.[17]

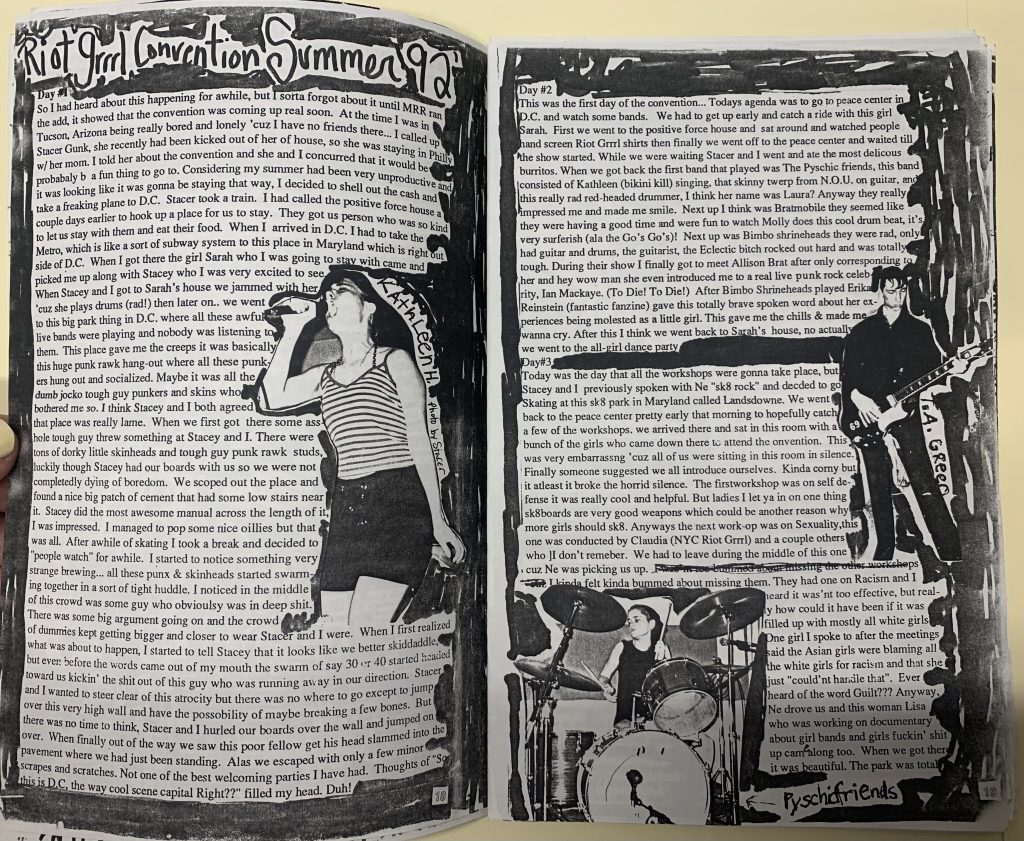

Image 2: Distribution copy of Gunk.<[18]

Image 3: Distribution copy of Gunk.

Once again, we would encourage students to note the visual elements in this image and how they look compared to the master. What has changed? Are the same pages next to each other? Why? Why are these images in black and white? What effect has copying had on the zine overall? How does handling this item feel compared to the master copy? What are you doing differently when holding this item?[19]

Bibliography

Buchanan, Rebecca. “Zines in the Classroom: Reading Culture.” The English Journal 102, no. 2 (2012): 71–77. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23365401.

Bickeem, Ramdasha. Ramdasha Bikceem Riot Grrrl Collection. Fales Library and Special Collections at NYU Special Collections, New York University Libraries, New York, NY.

Cassidy, Brian. “Identifying and Understanding Twentieth-Century Duplicating Technologies.” Class lectures at Rare Book School, Charlottesville, Virginia, June 12–17, 2022.

Hardesty, Michele, Alana Kumbier, and Nora Claire Miller. “Learning with Zine Collections in ‘Beyond the Riot: Zines in Archives and Digital Space.’” In Transforming the Authority of the Archive: Undergraduate Pedagogy and Critical Digital Archives, edited by Andi Gustavson and Charlotte Nunes 176-227. Ann Arbor: Lever Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.12752519.

Kempson, Michelle. “‘I Sometimes Wonder Whether I’m an Outsider’: Negotiating Belonging in Zine Subculture.” Sociology 49, no. 6 (2015): 1081–1095. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44016773.

Marcus, Sara. Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. New York: Harper Collins, 2010.

Matheny, Kathryn G. “No Mere Culinary Curiosities: Using Historical Cookbooks in the Library Classroom.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, & Cultural Heritage 21, no. 2 (2020): 79–97, https://doi.org/10.5860/rbm.21.2.79.

People of Color Zine Project. “About.” People of Color Zine Project. Accessed December 2, 2023, https://poczineproject.tumblr.com/about, archived December 2, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231202183122/https://poczineproject.tumblr.com/about.

Spencer, Amy. DIY: The Rise of Lo-Fi Culture. New York: Marion Boyars, 2008.

Walworth, Julia. “Oxford University: ‘Speed-dating’ in Special Collections: A Case Study.” In Past or Portal? Enhancing Undergraduate Learning Through Special Collections and Archives, edited by Eleanor Mitchell, Peggy Seiden, and Suzy Taraba, 30–34. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association, 2012.

Wright, Fred. “The History and Characteristics of Zines.” The Zine and E-Zine Resource Guide. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.zinebook.com/resource/wright1.html, archived September 21, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230921080408/https://www.zinebook.com/resource/wright1.html.

Endnotes

[1] Kathryn G. Matheny, “No Mere Culinary Curiosities: Using Historical Cookbooks in the Library Classroom,” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, & Cultural Heritage 21, no. 2 (2020): 79, https://doi.org/10.5860/rbm.21.2.79.

[2] Amy Spencer, DIY: The Rise of Lo-Fi Culture (New York: Marion Boyars, 2008), 64.

[3] Rebekah Buchanan, “Zines in the Classroom: Reading Culture,” The English Journal 102, no. 2 (2012): 71–77, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23365401.

[4] Fred Wright, “The History and Characteristics of Zines.,” The Zine and E-Zine Resource Guide, Accessed December 4, 2023, https://www.zinebook.com/resource/wright1.html, archived September 21, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230921080408/https://www.zinebook.com/resource/wright1.html.

[5] Spencer, DIY, 31.

[6] Spencer, 19.

[7] Spencer, 41.

[8] Julia Walworth, “Oxford University: ‘Speed-dating’ in Special Collections: A Case Study,” in Past or Portal? Enhancing Undergraduate Learning Through Special Collections and Archives, eds. Eleanor Mitchell, Peggy Seiden, and Suzy Taraba (Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association, 2012), 32.

[9] Michelle Kempson, “‘I Sometimes Wonder Whether I’m an Outsider’: Negotiating Belonging in Zine Subculture,” Sociology 49, no. 6 (2015): 1081–1095, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44016773.

[10] Sara Marcus, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution (New York: Harper Collins, 2010), 306–307.

[11] People of Color Zine Project, “About,” People of Color Zine Project, Accessed December 2, 2023, https://poczineproject.tumblr.com/about, archived December 2, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231202183122/https://poczineproject.tumblr.com/about.

[12] For a more detailed discussion on teaching with zines that expand students’ understanding of zine networks and the way those networks both pushed back on and replicated societal patterns of racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia, see Michele Hardesty, Alana Kumbier, and Nora Claire Miller, “Learning with Zine Collections in ‘Beyond the Riot: Zines in Archives and Digital Space,’” in Transforming the Authority of the Archive: Undergraduate Pedagogy and Critical Digital Archives, ed. Andi Gustavson and Charlotte Nunes (Ann Arbor: Lever Press, 2023), 176-227, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.12752519.

[13] Brian Cassidy, “Mimeograph,” Identifying and Understanding Twentieth-Century Duplicating Technologies (class lecture, Rare Book School, Charlottesville, Virginia, June 13th, 2022).

[14] Brian Cassidy, “Xerography,” Identifying and Understanding Twentieth-Century Duplicating Technologies (class lecture, Rare Book School, Charlottesville, Virginia, June 15th, 2022).

[15] Brian Cassidy, “Offset Lithography,” Identifying and Understanding Twentieth-Century Duplicating Technologies (class lecture, Rare Book School, Charlottesville, Virginia, June 14th, 2022).

[16] Jenna Freedman, email message to authors, October 27, 2023.

[17] 2 pages of master copy of GUNK #4, 1993, MSS. 354, Box 5, Folder 22, Ramdasha Bikceem Riot Grrrl Collection, Fales Library and Special Collections at NYU Special Collections, New York University Libraries, New York, NY. (hereafter cited as Master copy of GUNK #4, Ramdasha Bikceem Riot Grrrl Collection).

[18] Two pages of distributed copy of GUNK #4, Ramdasha Bikceem Riot Grrrl Collection.

[19] Two additional pages of distributed copy of GUNK #4, Ramdasha Bikceem Riot Grrrrl Collection.

Media Attributions

- IMG_2977

- IMG_2985

- unnamed