Reference

8 Reading Textiles: A Primer on Parsing Stories from Fabrics

Megan O'Connor

Introduction

Textiles as Documents

Textiles are a part of the material evidence of our lives. As artifacts, their stories and experiences are woven into the fibers of their being—literally and figuratively. “Reading” textiles unlocks opportunities for teasing out an object’s story at the micro-level (through fiber type, dyeing, construction techniques, and decoration) and the macro-level (through its overall structure, usage marks, and damage). Every element of the textile, from wear and damage to the fiber and dye used, is a clue to the object’s story and needs. This chapter offers an introduction to seeing and reading textiles as documents, providing additional resources for deeper investigations in Appendix 1, Recommended Resources. The chapter and resource list are divided into parallel segments, making it easier to locate additional resources about specific aspects of working with textiles.

History and Use

Textiles have been a crucial part of the fabric of daily life for millennia. From clothing to household linens to flags and beyond, textiles help to protect us from the elements, help us adapt to our environments, and allow us to express our identities (individual or shared). Textiles have also been at the forefront of scientific progress. In aviation history, for example, silks and muslin in balloons and early airplanes lifted aviators into the air, while silk and nylon parachutes brought them safely down again.[1]

Textiles in Archives

Textiles are typically more the domain of museums than of archives, but they do appear in archival collections, particularly in institutions that specialize in fields like fashion history. One example is the papers of Ann Getty, a prominent figure with personal connections to many famous twentieth-century designers. Getty’s collection is in the care of the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising in Los Angeles. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro’s Martha Blakeney Hodges Archives and Special Collections features a University Archives Textile Collection, which documents university history through items like the clothing of its founders, students, and faculty. Even collections that are not textile-themed may have textile elements. Textiles that are “peripheral to the research value of the paper materials” may receive limited usage, but a textile that is contextually important to its respective collection will augment the collection’s research value. For example, since early aeronautics relied heavily on fabric, textile scraps in aviation collections could provide additional research value.[2]

Variation in textiles is almost unlimited, but some small formats that could appear in an archival context include the following:

Fabric samples, scraps, or swatches

Souvenirs: Historical aircraft, significant clothing, etc.

Planning: Samples for interior design, fashion design, costume design

Accessories or personal decorations

Medals, ribbons, badges (military, political, etc.)

Armbands (identifying, etc.)

Patches

Miscellaneous items

Press passes

Bookmarks

Small crafts or samplers

Maps

Clothing

Hats, shirts, gloves, vests, ballet shoes, academic regalia

Most of these examples are drawn from collections in Wright State University Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives. (See Appendix 2 for a more detailed listing.)

Note that clothing may be significantly larger and bulkier than other textile items and will thus require more storage space. An archival institution should consider the storage space available, balanced with factors like the research value the object adds to the collection and the maintenance of donor relations.[3]

Examples in this Chapter

To illustrate concepts such as fiber types, construction techniques, damage, and handling concerns, this chapter will draw on the following objects from a private collection.

Object 1: A gold and blue silk baby bonnet, said to have been worn by an infant born in the 1890s (figure 1).

Object 2: A dark green velvet beaded purse, lined with silk, said to have been used by a woman born in the 1890s (figure 2).

Object 3: An embroidered linen doily made in the mid-twentieth century (figure 3).

Object 4: Beaded black cotton gloves owned by a woman born in the 1920s (figure 4).

Object 5: A yellow nine-patch quilt, likely dating to circa 1930–1950 (figure 5).

Handling Textiles

When handling historical textiles, it is important to protect yourself as well as the object you are studying. Like any historical object, textiles may contain toxic substances. (The upcoming section “Historical Use of Toxic Substances in Textiles” contains an overview of some of the not-so-lovely toxins that have been used to manufacture textiles.) To reduce the risk of accidentally ingesting any potentially harmful residues, always wash your hands thoroughly after handling textiles, before eating, drinking, or touching your face. [4]

Before beginning, prepare your surface. It should be clean and dry, with adequate space and support for the object you will be studying.

Like paper, textiles can be handled with clean, dry hands. Stow away jewelry like rings and watches in a secure location, to prevent them from snagging the threads in the textile. Additionally, if your fingernails are prone to damage, ensure that there are no rough spots that could catch the fabric. If your hands are prone to being rough and dry, to the point that they might snag the textiles, apply lotion well before you will be handling the textiles, and then wash your hands well to remove any residual oils.

Working with ungloved hands is the generally accepted best practice, since ungloved hands pose the least risk of damage to the textile. However, in some cases, well-fitting nitrile gloves may be worn to offer some protection from potential hazards in the textile. Fit is key: ill-fitting gloves (especially ones that are too big) can reduce sensitivity and dexterity, which can lead to accidentally damaging delicate textiles. Gloves that affect your ability to fold or unfold a tissue, tie a bow, fasten buttons, etc., might make it harder to handle textiles. Cotton gloves are not recommended, because they decrease the sensitivity of the fingertips more than nitrile gloves do. Additionally, they may catch or snag on delicate fibers, like silk or very fine cotton, in a Velcro-like manner.

Fine or delicate fabrics like silk can be especially prone to snagging (figure 6).

When handling or moving textiles, always support them as fully as possible to prevent damage or strain. Placing the item on a piece of archival tissue, in an archival box lid, on a piece of archival board, or a similar moveable surface, can allow the item to be rotated without being lifted or touched.

The silk velvet fabric of this purse is fragile and damaged (figure 7). Metal beads make areas disproportionately heavy. Lifting the bag without full support causes the bag to bend under the beads’ weight, risking new damage. In this case, an archival folder was used to support the item when moving it to be photographed (figure 8). Rotating the surface beneath the bag while studying it provides full support and reduces handling.

Exercise caution when inspecting the interior of an item. Do not force an object open.

The silk lining of the purse is shredded (figure 9). The jumbled fragments catch on each other, and are at risk of tearing. Forcing the bag open or attempting to separate the layers could cause the fabric to rip further, meaning the bag cannot be opened beyond this point.

The interior of this glove contains an embroidered tag with manufacturing information (figure 10). Portions of the tag are easily visible, but moving the tag to read the remaining information without forcing the glove open was difficult.

Never wear historical textiles or permit researchers to wear them or try them on. The force required to put the item on will likely result in damage. For those who desire to experience wearing historical clothing, there are abundant resources on making or purchasing replica garments.

Reading Textiles

Fiber: The Building Block

Textiles begin with fiber, which falls into two categories: natural and synthetic. Natural fibers are harvested from plant or animal sources. Cellulose (plant) fibers, such as cotton and linen, share some physical and chemical properties with paper, including a propensity toward acidity and loss of strength when exposed to acidic environments. Animal fibers, such as wool or silk (or human hair) are protein-based. Synthetic fibers can be formed from various materials. Rayon is derived from cellulose, and therefore also shares some properties with paper. Acetate fabric, a cousin of cellulose acetate film, is typically derived from cotton or wood. Other synthetic fibers, like polyester, are made of plastics. Textiles may be made of a single fiber or blend multiple fiber types.[5]

Fiber identification can be done using a microscope. Karen DePauw discusses the basics of identification techniques in The Care and Display of Historic Clothing. It is also possible to identify basic categories of fiber type by sight and touch. Many synthetic fibers, for example, may have a glossy appearance or a slippery feel. Linen has slubs (tiny areas of coarser thread) and looks wrinkly. Hone your skills by checking out the fiber content on your clothing tags, or take a field trip to a store and examine tags on clothing items there. As one example, a good thrift store might offer a broad sample of fiber types—natural and synthetic, “everyday” to “fancy”—all in one place. Get a sense for the trends in feel and appearance of the fabric, as well as the way the fabric behaves (e.g., rayon fabric sometimes feels heavy, and has a bit of a bounce to it).

Fiber type influences an object’s needs for care. Additionally, since synthetic fibers did not become available until the late-nineteenth century, fiber type can also help date items. The first artificial fiber, rayon, was developed in the 1880s and introduced commercially in the 1890s, followed by a plethora of new fibers in the twentieth century. For example:

1920s: Acetate

1930s: Nylon

1940s: Polyester[6]

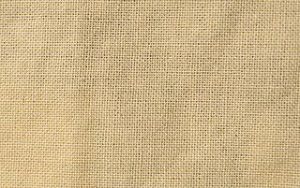

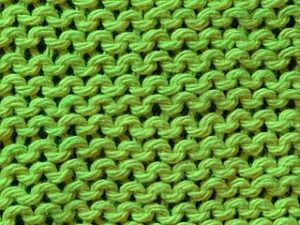

Fabric

Fibers are spun into threads or yarn and then transformed into fabric, usually through weaving or knitting. Woven fabric is the type of fabric jeans are made of. It is created using two sets of threads—one running vertically, and the other horizontally—so its structure looks like intersecting lines. It has limited stretch, except on the diagonal (bias). If its edges are “raw” (thread ends are visible), it may fray. Knitted fabric, the type of fabric used in t-shirts, sweaters, and socks, is made with one continuous thread. Loops of thread are pulled through an existing row of active loops, forming a structure that looks like stacks of interlocking v’s (or sometimes interlocking bars, like on the inside of a t-shirt). It is typically very stretchy. Since the fabric is formed with a continuous piece of thread, breaks in the thread can lead to unravelling (especially when the fabric stretches). Other structures may include crocheted fabric (which typically looks like stacks of the symbol π), or tatting (lace formed with rings or arcs of lark’s head knots, which also look like π) and other forms of lace.

Woven Fabric (figure 11).[7]

Two views of knitted fabric (figures 12 and 13). [8]

Crocheted stitches often look like π, with legs and a crossbar at top (figure 14). The top of a row of stitches typically looks like an interlocking chain.

Tatted material (figure 15). [9]

Chemical Components: Dyes and Treatments

The textile base (and other fibers) may be colored or altered through a multitude of chemical processes. These processes can be considered part of the object’s life history and may affect factors like physical stability and pH. The coloring or printed designs on a fabric can also help date an object.

A majority of coloring is achieved through dye, which may be synthetic or drawn from natural sources. Natural dyes can be plant-based (e.g., indigo, turmeric, walnut), or derived from sources like bugs (e.g., cochineal dye) or lichen (e.g., archil and cudbear dyes). Recipes for both natural and synthetic dyes can involve harsh chemicals, such as sulfuric acid. Some dyes require chemical mordants to set their color, which can affect a textile’s long-term stability. For example, iron-based mordants may oxidize, leading fabric (or particular portions of the fabric) to disintegrate. Undyed fabrics may have been bleached, a process that can be performed chemically (often through the use of a strong alkali, such as lye), through the use of sunlight, or a combination thereof.[10]

Fibers and fabrics may undergo additional chemical treatments to alter their physical properties. For example, mercerization, the process that makes things like mercerized cotton sewing thread shiny, involves treatment in a strong alkali, followed by treatment in acid to neutralize the base.[11]

The green fabric at center bottom and center right of the quilt block was originally a striped fabric (based on the even spaces between the green strands, and confirmed by a tiny remnant of surviving fabric at the left-hand side of the center-bottom square) (figure 16). One color has almost entirely deteriorated—possibly due to its fiber content, or possibly due to the treatments used to obtain the color.[12] The deterioration has revealed the quilt’s cotton batting, cotton backing, and an unfaded portion of the blue striped fabric at bottom left.

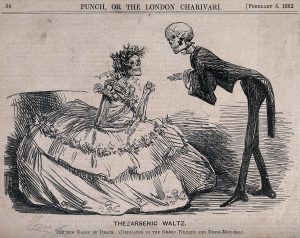

Historical Use of Toxic Substances in Textiles

Even in 1862, people questioned the safety of arsenic dyes (figure 17). [13]

Though arsenic green dye is notorious for its dangers, arsenic is far from the only toxic substance that was used in historical textile manufacturing processes. Historical dyeing guides document examples of dye recipes and processes, suggesting how and in what contexts certain chemicals and compounds may have been used. Keyword searches show that toxins like lead, mercury, and arsenic could play a role in a number of processes, either directly or indirectly.

Below are a few examples of ways in which certain toxins have been used.

Dyes

Arsenic: Greens (copper-based), Grey (aniline dye), Magenta (aniline dye), Carmine (Xylidine red), Indigo (some variations)

Mercury: Vermillion

Lead: Yellows (chrome, faint yellow gall dye; worked well on cotton), Orange (on cotton), Purple lake

Mordants

Mercury: e.g., “Roman purple”

Arsenic: (Various applications)

Treatments and finishing techniques

DDT: Military textiles

Mercury: Fur hats [14]

Not every object dyed a certain color (e.g., green) will necessarily have toxic contents. Nevertheless, always be cautious when working with historical material. For guidance on specific safety precautions, consult resources on how to handle hazards in collections.

Keeping it Together: Stitching and Connections

Fabric can be secured together using thread, pinning, or adhesive. When thread is used, the fibers in the thread do not necessarily match the fiber in the fabric (figures 18 and 19).

Shaping Up: Structural Elements and Padding

Objects that are thick, padded, or otherwise retain their own shape will include hidden structural layers. This can include fiber (e.g., cording, wool stuffing, and cotton or polyester batting like that used for quilts), animal products (baleen, quills, feathers), paper or plastic (e.g. in a baseball hat’s bill), or metal (e.g. nosepieces in facemasks). Often, these layers are internal and are only visible when an object is damaged. Never attempt to disassemble an object, to further any existing damage, or to create any damage, in an attempt to get a better glimpse at the interior structure. If the internal workings of an object must be known, consult with a professional conservator.[15]

The diamond pattern on the silk bonnet is interrupted by a line of “piping,” a piece of cord (probably cotton) wrapped with the silk fabric (figure 20). Although partly decorative, the piping also gently shapes the bonnet’s curves.

A portion of the stuffing or batting (likely wool) is visible near a hole in the right-hand side of the front edge of the quilted silk bonnet (figure 21).

Cotton batting (somewhat matted and clumpy, likely from repeated launderings) is visible through damage in the mid-twentieth-century quilt (figure 22).

Decorative Elements

A textile can be decorated in a number of ways, by applying material directly to the fabric (e.g., embroidery, paint, printing), or by affixing it through thread or adhesive (e.g., beads, sequins, buttons).[16]

Embroidered motif (figure 23).

Glass beads affixed with thread to (dusty) black gloves (figure 24).

Cleaning Textiles

Basic cleaning may be undertaken in-house with a variable suction vacuum, ideally with a filter. The textile object should be carefully laid out, and a piece of fine mesh laid on top of it or attached to the vacuum hose before vacuuming begins. Use a gentle suction. Textiles with any fragile areas, or loose threads, decorations, etc, should be vacuumed with care, or left unvacuumed if the suction is likely to cause further damage. All major cleaning, including wet-cleaning, should be left to conservators, who will be able to determine an appropriate treatment based on the sensitivities of the fibers, dyes, and other elements in the piece. Repairs and stabilization should also be done in consultation with a conservator.[17]

Storing Textiles

Textiles, like archival materials, are susceptible to damage by light, heat, and moisture, as well as dirt and pollution. These conditions can discolor textiles, fade dyes, and lead to embrittlement. At least in cellulosic fibers (like cotton and linen), the damage caused by these factors releases “acidic byproducts” that hasten the material’s decay.[18]

The original pinkish color of this silk bonnet is partly visible in areas where the ruffle’s folds protected the fabric from exposure to light (figure 25).

Moisture from an unknown source has caused these metallic beads on the bag to rust (figure 26). The rust contributed to the damage on the bag’s silk lining.

According to The National Park Service, an ideal environment for textiles is 65° to 75°F, with a relative humidity (RH) of about 50%. Lighting should be limited to 50 lux (lower, if possible), and UV should be avoided. If the textile is to be exhibited, limiting the display duration to four to six months will help to “ration” the object’s light exposure in a preservation-friendly way.[19]

Choosing Housing

Boxes used for textiles should be acid-free and lignin-free. Be cautious with metal-edged boxes—the metal corner reinforcements can have sharp edges that could snag textiles. Tissue paper used with textiles should also be acid-free. Unbuffered tissue is often the best choice for textile materials, because buffered tissue can be stiff enough to risk damage to delicate materials, or to snag materials when crumpled. If buffered tissue is used, it should not be used with protein-based fibers (e.g., silk and wool).[20]

In their guide, Care of Costume and Textile Collections, Jane Robinson and Tuula Pardoe suggest that small objects can be placed in Melinex/Mylar (polyester film) sleeves. Sleeves that can be fully opened would be ideal, so that the textile can be lifted from the open sleeve, if needed. A 3-sided or 2-sided enclosure could make it tempting to pull the textile out by one edge, which could cause strain, stretching, or tearing. Be cautious if you need to remove the textile from the sleeve, since, depending on the object’s material, loose threads, fragile areas, or decorations could be drawn to static charge in the polyester. Polyethylene (high and low density) and polypropylene storage bags may not be ideal for textile storage, as research by the Smithsonian Institution suggests that these materials may yellow textiles over time.[21]

Preparing Items for Storage

As with paper materials, textiles should be stored unfolded whenever possible to prevent damage from creasing or wear. If an item must be folded, use acid-free tissue to support the fold, which will prevent creasing and reduce strain. Gently crumple the tissue into a thin snake, and carefully fold the textile over the snake. Large, flat textiles can be rolled. This requires a sufficiently large tube, wrapping for the tube, covering material to protect the textile, and unbleached cotton twill tape to secure the package.[22]

Reformatting Textiles

Photography and digitization can increase accessibility and reduce handling on textile objects. Many museums have harnessed this opportunity through their online catalogs, but other format options exist. The Victoria and Albert Museum, for example, printed a treasury featuring images of some of their fragile but popular fabric samples. New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology issued a CD featuring digital editions of their fabric samples. At a minimum, the digital reformatting should capture the overall appearance of the object. Ideally, it will also capture details that may include fabric structure, color, designs or decorations on the fabric, and any tag or maker’s mark. Be aware of copyright. Clothing designs and printed artwork on clothing or fabrics may be under copyright protection.[23]

Conclusion: Exploring Textiles

Working with textiles is a multifaceted skill, but, fortunately, it is easy to practice. Because we spend our daily lives surrounded by textiles, the opportunities for honing textile-reading and textile-care skills are endless. The skills and concepts discussed in this chapter can generally be applied to any textile, new or old. If historical or vintage textiles are unavailable and you wish to supplement the resources in Appendix 1 with hands-on practice, you can practice by analyzing textiles at local stores, or in your own wardrobe and home.

Appendix 1. Resources for Further Study

Comprehensive Resources

DePauw, Karen. The Care and Display of Historic Clothing. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

Museums and Galleries Commission. Standards in the Museum Care of Costume and Textile Collections. Leicester, UK: Museums & Galleries Commission. Accessed June 5, 2023, https://collectionstrust.org.uk/resource/standards-in-the-museum-care-of-costume-and-textile-collections/, archived April 1, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220421175809/https://collectionstrust.org.uk/resource/standards-in-the-museum-care-of-costume-and-textile-collections/.

Robinson, Jane, and Tuula Pardoe. An Illustrated Guide to the Care of Costume and Textile Collections. London: Museums and Galleries Commission, 2000. Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www2.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/sites/default/files/folders/documents/leisureandculture/museums/museumsresourcescentre/illustratedguidetocareofcostumeandtextiles.pdf, archived November 3, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20211103205104/https://www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/sites/default/files/folders/documents/leisureandculture/museums/museumsresourcescentre/illustratedguidetocareofcostumeandtextiles.pdf.

Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute. “Taking Care.” Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.si.edu/mci/english/learn_more/taking_care/index.html, archived September 22, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220922030249/https://www.si.edu/mci/english/learn_more/taking_care/index.html.

Textile Specialty Group of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. “Textile Conservation Wiki.” Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/Textiles, archived March 21, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230321145335/https://www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/Textiles.

Textile Specialty Group of the American Institute for Conservation. Textile Conservation Newsletter Archives. Accessed April 16, 2022, https://resources.culturalheritage.org/textile-conservation-newsletter-archives/browse-issue-contents/, archived May 2, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230502042945/https://resources.culturalheritage.org/textile-conservation-newsletter-archives/browse-issue-contents/.

Textiles as Documents

Professionals Reading Garments

Arnold, Janet. Patterns of Fashion: Englishwomen’s Dresses and Their Construction, c.1660–1860. New York: Drama Book Specialists, 1972.

Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion series features exhaustively annotated patterns for extant garments, well-captioned photographs analyzing details of those garments, and historical imagery showing similar garments in use.

———. Patterns of Fashion: Englishwomen’s Dresses and Their Construction, c. 1860–1940. New York: Drama Book Specialists, 1972.

———. Patterns of Fashion: The Cut of Construction of Clothes for Men and Women, c. 1560–1620. New York: Drama Books, 1985.

Arnold, Janet, Jenny Tiramani, and Santina M. Levy. Patterns of Fashion 4: The Cut and Construction of Linen Shirts, Smocks, Neckwear, Headwear and Accessories for Men and Women, 1540–1660. Hollywood: Quite Specific Media Group, 2008.

Arnold, Janet, Jenny Tiramani, Luca Costigliolo, Sébastien Passot, Armelle Lucas, Johannes Pietsch. Patterns of Fashion 5: The Content, Cut, Construction and Context of Bodies, Stays, Hoops and Rumps c.1595–1795. London: School of Historical Dress, 2018.

Baumgarten, Linda. What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Through richly captioned pictures, Baumgarten analyzes and contextualizes garments in Colonial Williamsburg’s collection.

Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. “Confessions of a Costume Curator.” The Atlantic. August 18, 2017. Accessed June 13, 2023, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/08/confessions-of-a-costume-curator/536961/, archived October 8, 2017, at https://web.archive.org/web/20171008024356/https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/08/confessions-of-a-costume-curator/536961/.

Colonial Williamsburg. “Learning From Clothing.” Video, 5:13, July 29, 2022. Accessed June 10, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KfmKGwW9G_k, archived June 10, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230610223434/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KfmKGwW9G_k.

Colonial Williamsburg. “Studying Original Gowns.” Video, 4:08. March 21, 2023. Accessed June 10, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zruPCfbGffs, archived April 30, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230430010133/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zruPCfbGffs.

Cox, Abby. “I Bought the Most Incredible 1860s Woman’s Dress with TWO Bodices! 😭 | Antique Clothing Unboxing.” Video, 21:58. November 15, 2020. Accessed November 19, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2O4UvwN9aQ&list=PLAzJJkH_MerpZRPLBCueHwWLFL43Vzdu3, archived June 22, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230622112334/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2O4UvwN9aQ&list=PLAzJJkH_MerpZRPLBCueHwWLFL43Vzdu3.

Accessibility note: Abby Cox’s videos are professionally captioned on YouTube.

———. “People were *NOT* Smaller in the Past || Antique Victorian & Edwardian Clothing with 29+ inch Waists.” Video, 18:23. August 9, 2020. Accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-VR3ff0ZOHQ&pp=QAFIAQ%3D%3D, archived June 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230606000825/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-VR3ff0ZOHQ&pp=QAFIAQ%3D%3D.

Hart, Avril, and Susan North. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Fashion in Detail. New York: Rizzoli, 2000.

Hume, Sarah. Inside Out: Revealing Clothing’s Hidden Secrets. Accessed June 10, 2023, https://insideoutksum.wordpress.com/, archived June 11, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230601120340/https://insideoutksum.wordpress.com/

North, Susan, and Jenny Tiramani. Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns. London: V&A Pub., 2011.

History and Use

Montgomery, Florence. Textiles in America, 1650–1870: A Dictionary Based on Original Documents, Prints and Paintings, Commercial Records, American Merchants’ Papers, Shopkeepers’ Advertisements, And Pattern Books with Original Swatches of Cloth. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1984.

Montgomery provides details and context about the structure and histories of a multitude of fabric types. Additionally, if a fabric of known type is in the collection, this book can help determine the fabric’s potential material and properties.

Rutt, Richard. A History of Hand Knitting. Loveland, Colorado: Interweave Press, 1987.

Rutt’s book is one of the few comprehensive histories of knitting available. His collection of historical knitting manuals is available on The Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/victorianknittingmanuals.

Historical Fashion

The Barrington House. “Fashion Plates by Era.” Archived June 16, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20210616205132/http://bartoscollection.com/fashionplatesbyera.html.

Fukai, Akiko. Fashion: The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute — A History from the 18th to the 20th Century. Köln: Taschen, 2006.

See also the books under “Professionals Reading Garments” in the section “Textiles as Documents”.

Example Objects: Finding Additional Examples

Online Collections

Many museums include textiles in their online collections; these are some examples.

Augusta Auctions. “Search Past Sales.” Accessed June 11, 2023, https://augusta-auction.com/search-past-sales, archived June 4, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230604001455/https://augusta-auction.com/search-past-sales

Colonial Williamsburg. “Works – Costumes – The Collections – The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.” Accessed June 11, 2023, https://emuseum.history.org/groups/costumes/results, archived July 12, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220712061322/https://emuseum.history.org/groups/costumes/results

Fashion Institute of Technology. “The Museum at FIT.” Accessed June 20, 2023, https://fashionmuseum.fitnyc.edu/collections, archived June 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230606091730/https://fashionmuseum.fitnyc.edu/collections.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Search the Collection.” Accessed June 11, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search?showOnly=withImage&department=8%7C62, archived March 14, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230314222922/https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search?showOnly=withImage&department=8|62

The Ohio State University. “Fashion2Fiber.” The Historic Costume & Textiles Collection in the College of Education and Human Ecology at The Ohio State University. Accessed June 11, 2023, http://fashion2fiber.osu.edu/, archived May 28, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230528211815/http://fashion2fiber.osu.edu/.

Victoria & Albert Museum. “Explore the Collections: Textiles.” Accessed June 11, 2023, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/search/?id_category=THES48885, archived April 25, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230425084821/http://collections.vam.ac.uk/search/?id_category=THES48885

Find a Collection

The Costume Society of America maintains a list of institutions with costume collections, organized by region. Many other institutions, including small museums or local historical societies, may also have textiles in their collections.

Costume Society of America. “Collections.” Accessed June 11, 2023, https://costumesocietyamerica.com/resources/collections/, archived October 9, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20221009225023/https://costumesocietyamerica.com/resources/collections/

Handling Textiles

“Kathan L.” “Winterthur Museum, Care in Handling, Chapter 2, Textiles.” Video, 7:08. October 30, 2013. Accessed June 10, 2023, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNy6g9K1NAo, archived April 20, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230420100631/http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNy6g9K1NAo.

Reading Textiles

In addition to the sources suggested below, universities with programs on topics like textiles, fashion design, or home economics may have web resources dealing with the properties and uses of textiles.

Fiber: The Building Block and Fabric

Buchanan, Rita. A Weaver’s Garden. Loveland, Colorado: Interweave Press, 1987.

Buchanan discusses plant-based textiles and dyes.

Colton, Virginia, ed. Reader’s Digest Complete Guide to Needlework. Pleasantville, New York: Reader’s Digest Association, 1979. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://archive.org/details/readersdigestcom00colt/page/n7/mode/2up.

Craft encyclopedias like this one provide quick introductions to diverse crafts, offering insight on identifying fabric structures, stitching, and decorative techniques. Vintage encyclopedias can be especially useful for their inclusion of lesser-known crafts.

Monreagh Centre. “LINEN – Making Linen Fabric from Flax Seed – Demonstration Of How Linen Is Made” Video, 13:41. March 27, 2017. Accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TFuj7sXVnIU, archived April 5, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230405182417/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TFuj7sXVnIU.

Rudolph, Nicole. “Cotton Fabric 101: Supplies for Sewing.” Video, 34:46. July 18, 2021. Accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4DKwK1ohX8A, archived March 14, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230314162835/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4DKwK1ohX8A.

Accessibility note: Nicole Rudolph’s videos are professionally captioned on YouTube.

———. “Linen Fabric 101: Supplies for Sewing.” Video, 36:04 May 9, 2021. Accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUTA7L_LNFw, archived March 14, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230314162835/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUTA7L_LNFw.

———. “Silk Fabric 101: Supplies for Sewing.” Video, 35:08. March 28, 2021. Accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpiTld4rKfg, archived March 14, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230314163406/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpiTld4rKfg.

———. “Wool Fabric 101: Supplies for Sewing.” Video, 33:57. September 25, 2021. Accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Byu_Ry7ZVYE, archived March 14, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230314163436/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Byu_Ry7ZVYE.

Chemical Components: Dyes and Treatments

Brackman, Barbara. America’s Printed Fabrics: 1770–1890. Lafayette, California: C&T Publishing, 2004.

Dunbar, James. Smegmatalogia: Or the Art of Making Potashes and Soap and Bleaching of Linen. Edinburgh: 1736. Google Books. Accessed June 5, 2023, https://books.google.com/books?id=o0hiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false, archived June 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230606005007/https://books.google.com/books?id=o0hiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Ellis, Asa. The Country Dyer’s Assistant. Brookfield, Massachusetts: 1798. The Internet Archive. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://archive.org/details/countrydyersassi00elli/page/n7/mode/2up.

Marsh, J. T. An Introduction to Textile Finishing. London: Chapman & Hall Ltd., 1948. The Internet Archive. Accessed October 31, 2020. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.6810/page/n5/mode/2up.

This discusses a variety of treatments used to alter a fabric’s appearance or properties.

Slater, John William. The Manual of Colours and Dye Wares: Their Properties, Applications, Valuation, Impurities and Sophistications. For the Use of Dyers, Printers, Drysalters, Brokers, Etc. London, 1870. The Internet Archive. Accessed June 5, 2023. https://archive.org/details/manualcoloursan00slatgoog/page/n5/mode/2up.

Slater’s glossary-style work provides a bevy of information on the types of chemicals used to achieve various colors. This covers natural and synthetic dyes. It is a good resource for identifying contexts in which toxic substances may have been used.

Winterthur Library Digital Collections. “Textile Patterns and Designs.” Accessed June 17, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20181110015425/http://contentdm.winterthur.org/digital/collection/Textiles.

Winterthur’s digital collection includes swatch books and scrap books of fabric samples that can aid in understanding the evolution of fabric design.

Historical Use of Toxic Substances in Textiles

Museum of London. “Hazards in Collections”. Accessed November 17, 2023, https://hazardsincollections.org.uk/, archived January 29, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220129044039/https://hazardsincollections.org.uk/.

Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library. “Poison Book Project.” Accessed June 12, 2024, https://sites.udel.edu/poisonbookproject/, archived April 4, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240404120752/https://sites.udel.edu/poisonbookproject/.

Winterthur’s investigation provides additional avenues for discovering information about safety in working with potentially toxic collection items.

Shaping Up: Structural Elements and Padding

These case studies focus on structural undergarments (a famous example of structured textiles), but many other garments and textiles, like quilts and formal gowns, feature structural elements.

Arnold, Janet, Jenny Tiramani, Luca Costigliolo, Sébastien Passot, Armelle Lucas, and Johannes Pietsch. Patterns of Fashion 5: The Content, Cut, Construction and Context of Bodies, Stays, Hoops and Rumps c. 1595–1795. London: School of Historical Dress, 2018.

Banner, Bernadette. “Achieving That Classic Edwardian Shape: Reconstructing a 1902 Bust Bodice.” Video, 27:08. April 16, 2020. Accessed June 12, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CbzaBr4W4kk, archived March 14, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230314170020/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CbzaBr4W4kk.

Accessibility note: Bernadette Banner’s videos are professionally captioned on YouTube.

———. “What Did Victorian Corsets *Actually* Look Like? || Examining Corsets From the Symington Collection.” Video, 11:31. October 12, 2019. Accessed June 12, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5QUEf-8BKyE, archived March 21, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230321143454/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5QUEf-8BKyE.

Decorative Elements

Archaeological Resources

Textiles generally disintegrate in archaeological contexts, but archaeologists frequently recover and analyze robust textile-related artifacts like pins, buttons, and beads. Archaeological literature is thus a useful complement to textile studies.

Beaudry, Mary C. Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework and Sewing. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum. “Artifacts of Outlander.” Online exhibit, 2016. Accessed June 12, 2023, https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/outlander/index.html, archived September 18, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20210918163121/https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/outlander/index.html.

Ordoñez, Margaret T., and Linda Welters. “Textiles from the Seventeenth-Century Privy at the Cross Street Back Lot Site.” Historical Archaeology 32, no. 3 (1998): 81–90.

Cleaning Textiles

Conservation treatments should be undertaken by trained professionals, but these sources offer insight into the basic principles textile conservators employ, which may facilitate communication with a conservator.

American Institute for Conservation. “Find a Professional.” Accessed June 13, 2023, https://www.culturalheritage.org/about-conservation/find-a-conservator, archived June 11, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230601125635/https://www.culturalheritage.org/about-conservation/find-a-conservator.

Silvia, Kayla. “Washing Textiles: More Complicated than you Thought.” Textile Conservation: University of Glasgow. May 17, 2018. Accessed June 5, 2023, http://textileconservation.academicblogs.co.uk/washing-textiles-more-complicated-than-you-thought/, archived June 21, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220621060624/http://textileconservation.academicblogs.co.uk/washing-textiles-more-complicated-than-you-thought/.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “Cleaning Textiles.” Accessed June 5, 2023, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/c/cleaning-textiles/, archived September 24, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20210924065622/http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/c/cleaning-textiles/.

Storing Textiles

Minnesota Historical Society. “Rolling Textiles on a Tube – (Part 6 of 6) Conservation and Preservation of Heirloom Textiles.” Video, 11:57. December 9, 2009. Accessed November 17, 2023, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qiJz7-mzzxM, archived May 31, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230531124433/http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qiJz7-mzzxM

Accessibility note: All three of The Minnesota Historical Society videos cited in this section are professionally captioned on YouTube.

———. “Storage of Flat Textiles in Boxes – (Part 4 of 6) Conservation and Preservation of Heirloom Textiles.” Video, 6:24. December 9, 2009. Accessed November 17, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OYI5ExSdUHs, archived May 20, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230520095158/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OYI5ExSdUHs

———. “Storing Costumes in Boxes – (Part 3 of 6) Conservation and Preservation of Heirloom Textiles.” Video, 12:19. December 7, 2009. Accessed November 17, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4emRz2k296M, archived April 11, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230411041241/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4emRz2k296M.

Robinson, Jane, and Tuula Pardoe. An Illustrated Guide to the Care of Costume and Textile Collections. London: Museums and Galleries Commission, 2000. Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/sites/default/files/folders/documents/leisureandculture/museums/museumsresourcescentre/illustratedguidetocareofcostumeandtextiles.pdf, archived November 11, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20211103205104/https://www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/sites/default/files/folders/documents/leisureandculture/museums/museumsresourcescentre/illustratedguidetocareofcostumeandtextiles.pdf.

Robinson and Pardoe provide great step-by-step directions for safely storing and housing a variety of textiles and garments. They offer plenty of line drawings for guidance.

Wolf, Sara J. “A Simple Storage Mat For Textile Fragments.” National Park Service Conserve-O-Gram 16, no. 3 (September 2001). Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/mat16-3.pdf, archived March 27, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230327235124/https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/mat16-3.pdf.

Appendix 2. Examples of Textiles in Collections at Wright State University Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives

MS-1, Wright Brothers Collection: “Commemorative Bookmark – Flight of National Geographic-U.S. Army Air Corps stratosphere Balloon “Explorer II” (Bookmark made of balloon fabric)” (MS-1, Box 2A, Folder 10).

MS 37, Aeronautical Ephemera Collection I (Series III. Passes and Certificates): Scrap of wrecked balloon, silk press passes, silk armband (MS-37, Box 1, Folders 19 and 20).

MS-218, Josephine Schwarz Papers: “Honorary Doctoral Hood – University of Dayton,” “Child’s Ballet Shoes, Size 2 ½ C” (MS-218, Box 46, Folder 1; Box 48, Folder 2).

MS-223, William F. Yeager Aviation Collection: “Cloth Patches (Various),” “A[ir] F[orce] sewing kit”; “Road Map of West Africa (Cloth, Oct 1942),” (MS-223, Box 3; Box 3A).

SC-313, Albatross D. Va No. 7161/17 Fabric: Albatross aircraft fabric from 1917.

MS-432, Inland Children’s Chorus Collection: “Hair Ribbon and Dress Clipping from Alice Blue Gowns” (MS-432, Box 8, Folder 6).

MS-490, Ivan [&] The Sabers / The Lemon Pipers Collection: “Lemon Pipers T-Shirt” (MS-490, Box 2).

MS-636, George Barrett Family Papers: “Mary Evans Barrett’s cross-stitch watch case, marked “L L M,” “Mary Evans Barrett wedding dress and traveling dress fragments and note,” “Isaac M. Barrett Civil War Major Insignia and commission” (MS-636, Box 4, items 16-18).

Bibliography

Brackman, Barbara. America’s Printed Fabrics: 1770–1890. Lafayette, California: C&T Publishing, 2004.

Clarke, Rachel. “Preservation of Mixed-Format Archival Collections: A Case Study of the Ann Getty Fashion Collection at the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising.” The American Archivist 72, no. 1 (Spring-Summer 2009): 185–196.

Corbman, Bernard P. Textiles: Fiber to Fabric. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983.

Dunbar, James. Smegmatalogia: Or the Art of Making Potashes and Soap and Bleaching of Linen. Edinburgh: 1736. Google Books. Accessed June 5, 2023, https://books.google.com/books?id=o0hiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false, archived June 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230606005007/https://books.google.com/books?id=o0hiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Ellis, Asa. The Country Dyer’s Assistant. Brookfield, Massachusetts: 1798. The Internet Archive. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://archive.org/details/countrydyersassi00elli/page/n7/mode/2up.

Koelsch, Beth Ann, Kathelene McCarty Smith, and Jennifer Motszko. “Collecting Textiles: Is It Worth It?” Journal for the Society of North Carolina Archivists 3, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 2–17.

Museums and Galleries Commission. Standards in the Museum Care of Costume and Textile Collections. Leicester, UK: Museums & Galleries Commission. Accessed June 5, 2023, https://collectionstrust.org.uk/resource/standards-in-the-museum-care-of-costume-and-textile-collections/, archived April 21, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220421175809/https://collectionstrust.org.uk/resource/standards-in-the-museum-care-of-costume-and-textile-collections/.

National Park Service. “Buffered and Unbuffered Storage Materials.” Conserve-O-Gram 4, no. 9 (July 1995). Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/04-09.pdf, archived March 27, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230327234912/https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/04-09.pdf.

———. Museum Handbook (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service Museum Management Program, 2002). Appendix K. Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/mhi/appendix%20k.pdf, archived April 1, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230401193228/https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/mhi/appendix%20k.pdf.

Ordoñez, Margaret, and Linda Welters. “Textiles from the Seventeenth-Century Privy at the Cross Street Back Lot Site.” Historical Archaeology 32, no. 3 (Fall 1998): 81–90.

Palmer, Alexandra. “Creating Desire and Knowledge in Museum Costume and Textile Exhibitions.” Fashion Theory 12, no. 1 (2008): 31–64.

Peacock, Elizabeth. “The Effect of Internal Acidity on Textile Deterioration.” Paper presented at Art Conservation Training Programs Conference, University of Delaware, April 1980. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256581262_The_effect_of_internal_acidity_on_textile_deterioration.

Robinson, Jane, and Tuula Pardoe. An Illustrated Guide to the Care of Costume and Textile Collections. London: Museums and Galleries Commission, 2000. Accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/sites/default/files/folders/documents/leisureandculture/museums/museumsresourcescentre/illustratedguidetocareofcostumeandtextiles.pdf, archived November 2, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20211103205104/https://www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/sites/default/files/folders/documents/leisureandculture/museums/museumsresourcescentre/illustratedguidetocareofcostumeandtextiles.pdf.

Slater, John William. The Manual of Colours and Dye Wares: Their Properties, Applications, Valuation, Impurities and Sophistications. For the Use of Dyers, Printers, Drysalters, Brokers, Etc. London, 1870. The Internet Archive. Accessed June 7, 2023, https://archive.org/details/manualcoloursan00slatgoog/page/n5/mode/2up.

Textile Research Center. “Mercerisation.” TRC Leiden. Last modified April 26, 2017. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20230328121909/https://www.trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/tools/fibre-preparation/mercerisation.

University of Delaware. “Safer Handling & Storage Tips.” Poison Book Project. Accessed November 23, 2024, https://sites.udel.edu/poisonbookproject/handling-and-safety-tips/, archived November 15, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20241115202827/https://sites.udel.edu/poisonbookproject/handling-and-safety-tips/.

Utah State University Cooperative Extension. “From Fiber to Fabric: Acetate.” Utah State University Digital Commons. Accessed June 7, 2023, https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curall/1508/, archived May 6, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220506142353/https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curall/1508/.

Endnotes

[1] For one example of an early airplane made with fabric, see Orville Wright and Wilbur Wright, The 1903 Wright Flyer, inventory number A19610048000, 1903, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, accessed June 24, 2023, https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/1903-wright-flyer/nasm_A19610048000, archived June 16, 2020, at https://web.archive.org/web/20200616172958/https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/1903-wright-flyer/nasm_A19610048000.

[2] Rachel Clarke, “Preservation of Mixed-Format Archival Collections: A Case Study of the Ann Getty Fashion Collection at the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising,” The American Archivist 72, no. 1 (Spring-Summer 2009): 187; Beth Ann Koelsch, Kathelene McCarty Smith, and Jennifer Motszko, “Collecting Textiles: Is It Worth It?” Journal for the Society of North Carolina Archivists 3, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 5–6, 13–14.

[3] Koelsch, Smith, and Motszko, “Collecting Textiles,” 14–16.

[4] “Safer Handling & Storage Tips,” Poison Book Project, University of Delaware, accessed November 23, 2024, https://sites.udel.edu/poisonbookproject/handling-and-safety-tips/, archived November 15, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20241115202827/https://sites.udel.edu/poisonbookproject/handling-and-safety-tips/.

[5] Elizabeth Peacock, “The Effect of Internal Acidity on Textile Deterioration,” (paper presented at Art Conservation Training Programs Conference, University of Delaware, April 1980), 47, accessed October 31, 2020, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256581262_The_effect_of_internal_acidity_on_textile_deterioration; Bernard P. Corbman, Textiles: Fiber to Fabric (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983), 333.

[6] Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “rayon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed June 21, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/technology/rayon-textile-fibre, archived April 10, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230410011950/https://www.britannica.com/technology/rayon-textile-fibre; Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “nylon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed June 21, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/science/nylon, archived March 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230306022805/https://www.britannica.com/science/nylon; Utah State University Cooperative Extension, “From Fiber to Fabric: Acetate,” Utah State University Digital Commons, accessed June 7, 2023, https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curall/1508/, archived May 6, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220506142353/https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curall/1508/; Corbman, Textiles, 374. Note that polyester was patented in the 1940s, but commercially introduced in the 1950s.

[7] Henningklevjer~commonswiki, Weave.jpg, 2006, Wikimedia Commons, accessed March 22, 2022, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Weave.jpg, archived January 10, 2024 at, https://web.archive.org/web/20240110201052/https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Weave.jpg.

[8] Hobbsansak, Slätstickning.jpg, 2017, Wikimedia Commons, accessed April 13, 2022, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sl%C3%A4tstickning.jpg, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110201007/https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sl%C3%A4tstickning.jpg; Stilfehler, Strickmuster – Basismuster, links.JPG, 2015, Wikimedia Commons, accessed April 13, 2022, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Strickmuster_-_Basismuster,_links.JPG, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110201050/https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Strickmuster_-_Basismuster,_links.JPG.

[9] Franz van Duns, 2021-03-21 DSG0835 butterfly-shaped handiwork in tatting technique (high resolution).jpg, 2021, Wikimedia Commons, accessed April 13, 2022, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2021-03-21_DSG0835_butterfly-shaped_handiwork_in_tatting_technique_(high_resolution).jpg, archived May 25, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230525013645/https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2021-03-21_DSG0835_butterfly-shaped_handiwork_in_tatting_technique_(high_resolution).jpg.

[10] Asa Ellis, The Country Dyer’s Assistant (Brookfield, Massachusetts, 1798), 15–16, 68, The Internet Archive, accessed April 13, 2022, https://archive.org/details/countrydyersassi00elli/page/n7/mode/2up; John William Slater, The Manual of Colours and Dye Wares: Their Properties, Applications, Valuation, Impurities and Sophistications. For the Use of Dyers, Printers, Drysalters, Brokers, Etc. (London, 1870), 23, 61, 83–84, 178–179, 192, The Internet Archive, accessed June 7, 2023, https://archive.org/details/manualcoloursan00slatgoog/page/n5/mode/2up; Barbara Brackman, America’s Printed Fabrics: 1770–1890 (Lafayette, California: C&T Publishing, 2004), 101; James Dunbar, Smegmatalogia: Or the Art of Making Potashes and Soap and Bleaching of Linen (Edinburgh, 1736), 22–24, 26–29, 32–33, 38, The Internet Archive, accessed June 5, 2023, https://books.google.com/books?id=o0hiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false, archived June 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230606005007/https://books.google.com/books?id=o0hiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[11] Textile Research Center, “Mercerisation,” TRC Leiden, April 26, 2017, accessed June 7, 2023, https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/tools/fibre-preparation/mercerisation archived March 28, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230328121909/https://www.trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/tools/fibre-preparation/mercerisation.

[12] For analysis of a similar phenomenon, see Margaret Ordoñez and Linda Welters, “Textiles from the Seventeenth-Century Privy at the Cross Street Back Lot Site,” Historical Archaeology 32, no. 3 (Fall 1998), 87–88.

[13] “The Arsenic Waltz”, 1862, etching, in Punch, February 8, 1862, Wellcome Library, Wikimedia Commons, accessed March 29, 2022, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Two_skeletons_dressed_as_lady_and_gentleman._Etching,_1862._Wellcome_V0042226_(crop_and_cleaned_up).png, archived August 9, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240809170908/https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Two_skeletons_dressed_as_lady_and_gentleman._Etching,_1862._Wellcome_V0042226_(crop_and_cleaned_up).png. Original image appears at https://wellcomecollection.org/works/awbr7whm/items, archived December 8, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20221208202538/https://wellcomecollection.org/works/awbr7whm/items.

[14] Slater, The Manual of Colours and Dye Wares, 18, 26–27, 74, 99, 117–18, 121, 138, 196, 207; Museum of London, “Mercury and Its Compounds: Where Might You Find Them?” 2019, accessed March 29, 2022, https://hazardsincollections.org.uk/mercury-and-its-compounds/where-might-you-find-them, archived August 15, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220815070708/https://hazardsincollections.org.uk/mercury-and-its-compounds/where-might-you-find-them; Museums and Galleries Commission, Standards, 61.

[15] For an example of cording used in an extant garment, see the following petticoat in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Petticoat, accession number 1992.365, 1830s, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, accessed June 24, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/82076, archived December 25, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20211225121406/https:/www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/82076.

[16] For one example of a lacy embroidery technique, see this eyelet embroidery Petticoat, accession number 2009.300.3177, 1860-1865, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, accessed June 24, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158085, archived August 9, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240809180545/https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158085. For an example of printing in historical textiles, see this Handkerchief, accession number 1993–142, 1800–1811, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia, accessed June 24, 2023, https://emuseum.history.org/objects/2080/handkerchief, archived June 4, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230604000850/https:/emuseum.history.org/objects/2080/handkerchief. For a glimmering glimpse of the Roaring Twenties, see this heavily decorated Sequined & Beaded Dress, 1920s, August Auctions, Vermont, accessed June 24, 2023, https://augusta-auction.com/search-past-sales?view=lot&id=13538&auction_file_id=29, archived June 4, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230604001325/https:/augusta-auction.com/search-past-sales?view=lot&id=13538&auction_file_id=29.

[17] Jane Robinson and Tuula Pardoe, An Illustrated Guide to the Care of Costume and Textile Collections (London: Museums and Galleries Commission, 2000), 21.

[18] Peacock, “Internal Acidity,” 47, 49; Museums and Galleries Commission, Standards in the Museum:Care of Costume and Textile Collections (Leicester, UK: Museums & Galleries Commission), 36–37, section 7.22, accessed June 5, 2023, https://collectionstrust.org.uk/resource/standards-in-the-museum-care-of-costume-and-textile-collections/, archived April 1, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220421175809/https://collectionstrust.org.uk/resource/standards-in-the-museum-care-of-costume-and-textile-collections/.

[19] For readers working in Celsius, the United Kingdom’s Museums and Galleries Commission has suggested a temperature range of 18°C, +/- 2°. Museums and Galleries Commission, Standards, 36-37, section 7.18, 7.25; National Park Service, Museum Handbook (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service Museum Management Program, 2002), Appendix K, section D4, accessed April 16, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/mhi/appendix%20k.pdf, archived April 1, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230401193228/https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/mhi/appendix%20k.pdf; Alexandra Palmer, “Creating Desire and Knowledge in Museum Costume and Textile Exhibitions,” Fashion Theory 12, no. 1 (2008): 38, 40.

[20] Museums and Galleries Commission, Standards, 42, section 9.7.; National Park Service, “Buffered and Unbuffered Storage Materials,” Conserve-O-Gram 4, no 9 (July 1995), 4, accessed April 16, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/04-09.pdf, archived March 27, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230327234912/https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/04-09.pdf.

[21] Robinson and Pardoe, Care of Costume and Textile Collections, 25; Mary Ballard and Odile Madden, “General Guide to Plastics for Storage,” in Mary Ballard, Post to “Are Ziploc Bags okay for multi year object storage?,” January 13, 2022, Connecting to Collections Care Community, American Institute for Conservation, accessed June 22, 2023, https://community.culturalheritage.org/viewdocument/re-are-ziploc-bags-okay-for-multi, archived August 9, 2024, at https://community.culturalheritage.org/viewdocument/re-are-ziploc-bags-okay-for-multi?CommunityKey=efc8a209-1e74-4c1b-80d7-cb26db836184&tab=librarydocuments.

[22] Robinson and Pardoe, Care of Costume and Textile Collections, 18, 26, 30–31, fig. 28; Museums and Galleries Commission, Standard 43–44, section 9.14.

[23] Clarke, “Preservation of Mixed-Format Archival Collections,” 189; Museums and Galleries Commission, Standards, 26.

Media Attributions

- Private: Baby Bonnet © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Purse © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Embroidered Doily © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Black Gloves © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Quilt Block © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Detail of Snag on Silk Bonnet © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Tear in Purse © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Rotating Purse © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Interior of Purse © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Interior of Glove © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Weave.jpg © Henningklevjer~commonswiki is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Private: Slätstickning.jpg [Stockinette Stitch] © Hobbsansak

- Private: “Stricken: glatt rechts gestrickt, Links-Ansicht” [Knitting: stockinette stitch, purl view] © Stilfehler

- Private: Crocheted Edging © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: 2021-03-21 DSG0835 butterfly-shaped handiwork in tatting technique (high resolution).jpg © Franz van Duns

- Private: Damage on Quilt © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: A skeleton gentleman at a ball asks a skeleton lady to dance; representing the effect of arsenical dyes and pigments in clothing and accessories. Wood engraving, 1862. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection. © Wellcome Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Private: OConnor Img17-BonnetThreads © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: OConnor Img18-PurseRepair(1) © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Bonnet Piping © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Bonnet Batting © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Quilt Batting © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: OConnor Img24-EmbroideredMotif is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Glove Beading © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Fading on Bonnet © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Rusting Beads on Purse © Megan O'Connor is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license