Pedagogy

20 Online and Interactive: Bringing a Digitized Manuscript to (Virtual) Life

Miriam Intrator

Introduction

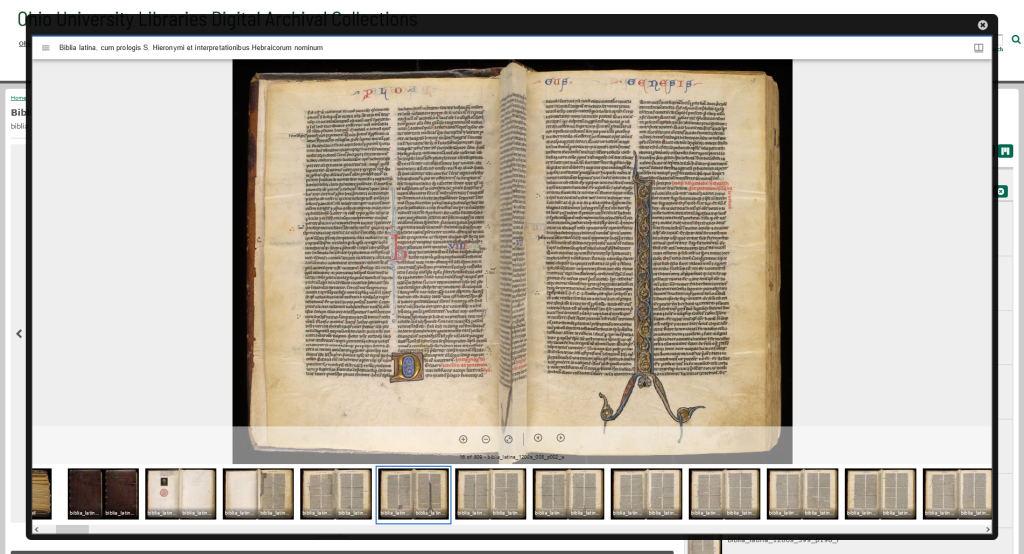

The signature item in the Rare Book Collection of Ohio University Libraries’ Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections is a late-thirteenth-century illuminated Latin manuscript Bible.[1] Created in Southern France and previously owned by nineteenth-century British designer, author, socialist activist, and bookmaker William Morris, the Bible was donated in 1979 in memory of Ohio University alumnus Carr Liggett. It was cataloged and celebrated as the millionth volume added to the Libraries’ collection.[2] The Bible is our only complete manuscript codex and is used extensively for instruction in a wide variety of classes to support the teaching of everything from book history and religious studies to Latin and art history.

Due to its central and frequent inclusion in course instruction, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdown revealed a crisis in access to the Bible, as it did to all collections materials. How could I continue to rely on the Bible for so much of my instruction if teaching was going to be remote for an indefinite period? As a newcomer to thinking about online instruction, my first challenge was getting over the notion that teaching primary source literacy requires physical interaction with the original primary sources. I am a strong proponent of digitization and of the increased access and discoverability that digital surrogates allow. However, I had never previously placed those front and center in my teaching. The pandemic left no choice.

This mental shift has proven to be critically important to my ability to maximally impact students, to meet students where they are, and to reach students who I would not reach otherwise. In addition, with digital tools available online that highlight materials from our collections like the Bible, there is potential for researchers, instructors, and librarians elsewhere to find them, use them, research with them, or be inspired by them. I know that I was utterly reliant on learning from pre-existing online content when building this tutorial and I hope that it, and this chapter, may be helpful to others in turn.

As a first step, I began conversations with my colleagues in Digital Initiatives who agreed to fast-track digitization of the Bible early during the summer of 2020. At over 800 bound pages recto and verso, this was no small undertaking. Digital Imaging Specialist Erin Wilson noted that “Working with the bible was different from other bound book photography due to the size, age, and materials.”[3] The results, however, are beautiful and incredibly useful high-resolution files.

Of particular interest here is that having the Bible fully digitized and available online enabled me, in advance of the fall 2020 remote semester, to make it the focus of an asynchronous, interactive tutorial using SpringShare’s LibWizard.[4]

In this chapter I will describe the tutorial, its creation process, my learning objectives when I teach with the Bible and how they evolved with the tutorial, tutorial usage, and student and faculty response. I will conclude with brief suggestions for anyone who may want to create a similar learning experience. Importantly, while SpringShare is a paid product that I am fortunate my library subscribes to, it is not required to embark upon similar projects.

How It Began

To take a step back, I want to explain my motivation for creating a tutorial around a single collection item. One of my biggest concerns and challenges as a rare book librarian is minimizing the intimidation factor that often surrounds rare books. Most university students have no prior experience visiting a special collections reading room or handling a rare book. The common perception among students is that neither the materials nor the space are for them. Instead, most imagine that special collections, and by extension those of us who work in these spaces, exist only to serve “important” and high-level researchers producing scholarly books or other major projects. My primary goal in any interaction with a student or other potential visitor is to make them feel welcome, that they belong, and free to express curiosity to see and learn more.

Almost nothing is equal parts as intimidating, alluring, and impactful as the experience of introducing students to our thirteenth-century manuscript Bible, which we refer to as the Biblia Latina. Regardless of whether students feel any religious or spiritual connection to the content, the Bible is familiar, and recognized as a text many consider sacred. This does create a tension between the reverence many inherently feel for a beautiful and very old Bible, and the need to diminish any sense of awe that impedes student comfort with seeing it as a learning object that is fully accessible to them. Letting students carefully examine and touch 800-year-old parchment, covered in what is to most a bafflingly miniscule, undecipherable script, and beautifully enhanced with colorful illuminations of fantastical creatures, generates questions and excitement. Historically, this introduction exclusively occurred during in-person, hands-on instructional sessions, guided by the following learning objectives:

- Students will be empowered to confidently, comfortably, and safely handle and interact with an original thirteenth-century illuminated manuscript codex;

- Students will become familiar with some basic terminology related to medieval manuscripts, including concepts and techniques such as the scriptorium, ruling, illumination, parchment, rubrication, manicule, and so on;

- Students will develop an initial understanding of archives and special collections, where they are located, the types of materials they contain, who I am, and how to contact me;

- Students will recognize that medieval manuscripts are not just kept behind glass in museums. They will make the distinction that anyone is welcome to visit our archives and special collections and request access to materials, including a unique item like the Bible.

Developing the Tutorial

In March 2020, when hands-on and in-person sessions became impossible, like so many of my fellow librarians I quickly pivoted to learning to create interactive asynchronous tutorials as a means to continue primary source literacy and special collections instruction sessions in the remote environment.[5] Within that context, I knew I wanted to develop an entire tutorial around the Biblia Latina. The central challenge was to create a meaningful interactive experience, without any of the traditional sensory elements that wowed students, that would still be impactful.

In developing the tutorial, my guiding consideration was how to translate my classroom learning objectives into the virtual environment. All but one required a total rewrite. The edited versions for online learning became:

- Students will be empowered to critically analyze and reflect on the making of medieval manuscripts;

- (remained exactly the same) Students will become familiar with some basic terminology related to medieval manuscripts, including concepts and techniques such as the scriptorium, ruling, illumination, parchment, rubrication, manicule, and so on;

- Students will develop a sense of curiosity about and desire to visit archives and special collections in person and feel comfortable getting in contact with me;

- Students will consider and articulate the value of information and will identify any barriers to equal access to information.

I also had to consider the content to include. An online tutorial breaks content up into small, digestible bits. This hopefully helps to keep students engaged while covering the maximum amount of material. I began by reflecting on the elements students were most interested in and curious about during in-class sessions. These became my main guiding categories: illumination, script, ruling, substrate, and marginalia. Once I knew the areas I wanted to focus on, I began selecting relevant images and writing text and questions. The next step was to try to liven up the content. Digitized images are flat on the screen and it is easy to lose the sense of paging through a book. I created short videos to explain some of the more complex elements and to try to insert a sense of movement and interaction. I added reflection questions and an option to draw and doodle. The final step was to share it with faculty from various departments who often teach with the Bible and incorporate their feedback into the final product.

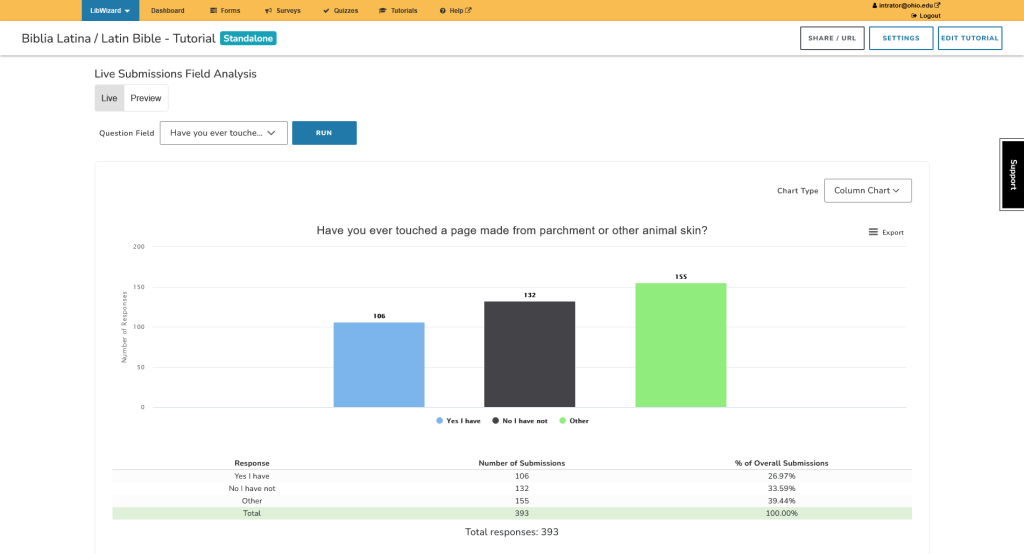

I continue to be open to new ideas and to consider ways in which I can improve the learning experience for students. The completed tutorial includes a combination of text, video, still images, links out, an invitation to draw, questions that students must answer correctly in order to move on, and opportunities to reflect. The drawing and phrasing of some of the questions is intended to insert some fun and to gauge student response. For example, the slide asking students if they have ever touched a page made of parchment offers three possible responses:

Option three, “No I have not, but now I really want to!”, and its expression of excitement and desire to learn more and experience the Bible in person, has been selected most often by students, receiving 39.44% of all responses. The other two, “Yes I have” and “No I have not”, received 26.97% and 33.59% respectively. It is not scientific, but it gives me a general sense of how students are learning and reacting.

Results and Assessment

Since going live in August 2020, the tutorial has been assigned to and completed by almost 400 students. Classes that regularly assign the tutorial include, from history: “Western Civilization: Antiquity to 1500” and “Life, Love, and Death in the Medieval World”; from Classics and Religious Studies: “Hebrew Bible” and “Beginning and Intermediate Latin”; and from English: “History of the Book and Printing.” The response has been overwhelmingly positive. The freedom to explore digitally and independently cannot be replicated in the classroom environment, no matter how friendly and inviting. In person, students are always constrained by time, their own comfort level (or lack thereof), and the need to take turns interacting with the physical Bible as a shared experience and under close supervision with regards to proper handling. In the classroom I am one person, standing at the front of the room with a single manuscript on the table in front of me. Students generally rotate, taking turns to view a few pages up close, but they are not all able to be in front of the Bible throughout the entire session. Online, they are one-on-one and face-to-face, so to speak, with the resource and able to explore it as deeply as they choose. Inviting students to dive into the digitized manuscript, aided along in their journey by the prompts provided by the progression of the tutorial, enhances their learning as they can study and consider the object in their own time and in the digital space in which most of them feel completely at home and empowered.

Since the return to in-person instruction, several faculty members still regularly assign the tutorial before bringing their classes in for instruction sessions. Completion of the tutorial demonstrably gets students excited about then getting to engage with the physical Bible in person. Because students now come to class already knowing something about the Biblia Latina, they are also more confident about interacting with it and asking me questions about specific elements that intrigued or confused them. Students who are surprised by the Bible in the classroom as a first introduction to it tend to be far more intimidated by its age and beauty. They are reluctant to touch it and very worried about somehow damaging it. I find that students are less hesitant to interact with the Biblia Latina after completing the tutorial. Having some background knowledge about it and having had the time and freedom to explore it digitally gives students more confidence in the classroom.

Assigning the tutorial ahead of meeting means there is less need for me to talk and explain, freeing up precious class time for student-led questioning, discussion, hands-on exploration, and, their favorite part, picture taking. The tutorial also enables students in classes too large for in-person sessions to still learn about and engage with the Bible, something that was impossible before it was digitized or featured in the tutorial. In this way I, and the Bible, are reaching more students than ever before. History professor Miriam Shadis, who teaches one of those large classes, assigns the tutorial for extra credit. She comments, “It was particularly wonderful during COVID, when there was no chance of sending students to the library to see the Bible, but even now, it’s really neat because I encourage students to go and see the “real thing” after they take the tutorial, and some of them actually have done it! They are always amazed that we have this beautiful book in the library, and that we can know so much about how it was made.”[6]

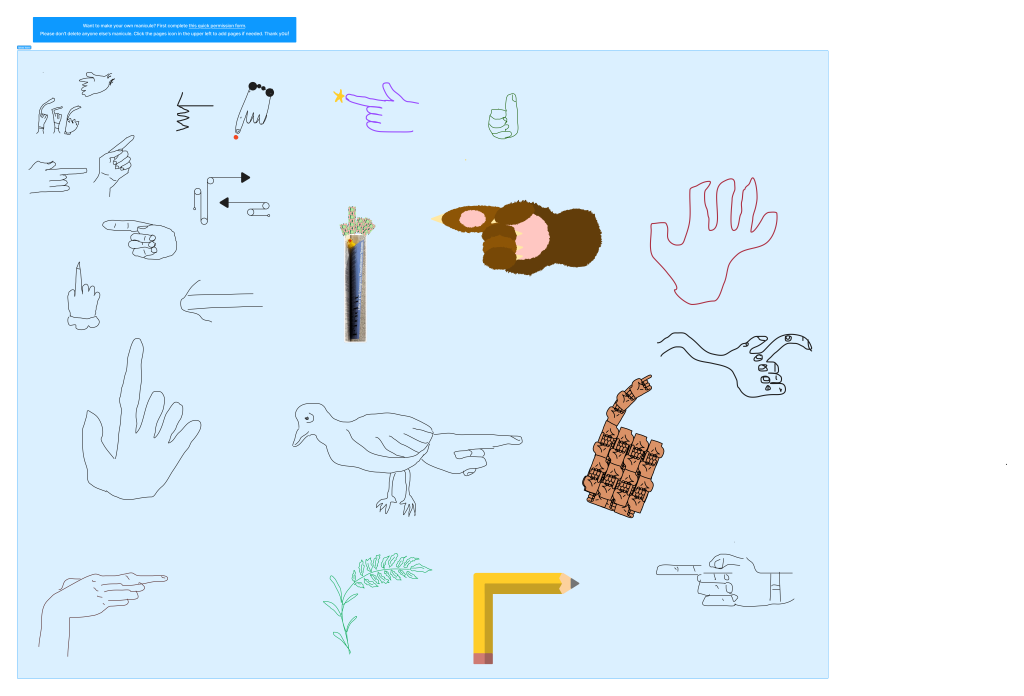

Two of my favorite parts of the tutorial, which I hope are also two of the most impactful, are, first, the reflection questions inspired by the Association of College and Research Libraries’ Framework for Information Literacy—in particular: Information has Value.[7] Second, inserting some fun and creativity into the learning experience. After learning what a manicule is and seeing many examples in the Biblia Latina, students are invited to draw their own using Google Jamboard.[8] This is the only optional element of the tutorial, but most students still give it a try and the results are delightful.[9]

Professor Shadis has also noticed how popular the manicules are. In an email she wrote that students “love the odd details, like all the manicules; in student written responses to the tutorial (I have them take the tutorial and write a brief paper on it), they almost always point these out.”[10]

The framework question is divided into two parts. Both are required and have space for open text response. I am regularly moved by how students respond to these questions. By how they are alert and sensitive to inequities in our society and how detrimental these are in the realm of education, information, and knowledge. Below I share a select few responses to demonstrate the critical thinking and engagement that occurs during the completion of this tutorial.

Part one of the question is: “We live in a very different time in which information is everywhere, but inequities in access still exist. Reflect on what the phrase ‘information has value’ means to you.” Select responses include:

After learning about the process of making this type of Bible, I think the phrase “information has value” implies that people with information are wealthy, at least during the era in which this was the standard practice of bookmaking. Nowadays, we might take information for granted because of how easily accessible it can be for most people.

To me, it seems related to the idea of knowledge is power. Access to information gives a person more knowledge. On the other hand, bad information feels useless, if not harmful. I suppose the value of information would depend on the information’s validity.

Education isn’t actually as common as we may think. It disadvantages us to forget that going to college is a privilege.

Information gives access to what has happened in the past and can guide what will happen in the future.

Part two of the framework question asks: “Now reflect on what you see as a barrier to equal access to information today.” Responses include:

I think a big barrier in access to information is not everyone can afford or go to college or have a high school diploma, as well as not having access to as many libraries or under funding for public schools, all of which especially [affects] minorities.

A huge barrier to accessible information today would be subscription to information services. This includes the cost of internet and the cost of sources such as the New York Times. Most information platforms are run on a subscription service thus gatekeeping information.

I think we’re all aware of the inequalities of access to information, like access to a decent education, access to internet, books, etc. But I think there’s also inequalities when it comes to knowing how to access information that you have access to. Like knowing how to properly research something, how to critically think, these aren’t things that everyone is taught, and that limits how much one can learn.

I think not having reliable access to internet, or having access but not knowing how to use it, can be a huge barrier to equal access to information in today’s world. I get most of my information from the internet, but my grandma, who doesn’t know how to use a computer or a smartphone, often is unaware of certain pieces of information that I think are common knowledge.

Just in these few responses I see evidence of critical thinking and of making connections between the Bible, the past it represents, and what students learned in the tutorial, with the present moment. As a teaching librarian, this feels like pedagogical success. It inspires me to consider other ways I can challenge myself to extend the reach of primary source literacy instruction and access to more and more items from the collections beyond the walls of the traditional classroom.

Recommendations & Conclusion

For anyone interested in developing a similar experience, whether to introduce students to medieval manuscripts or to anything else in your collections, LibWizard or other subscription or paid platforms are not required to create a successful tutorial. Similarly, for anyone who does not have materials physically or digitally available in your home institution, there are a huge and ever-growing number of free, open-access, digital materials available for use, study, research, and download from collections all over the world. Proper attribution is of course required, and asking for usage permission is strongly encouraged.

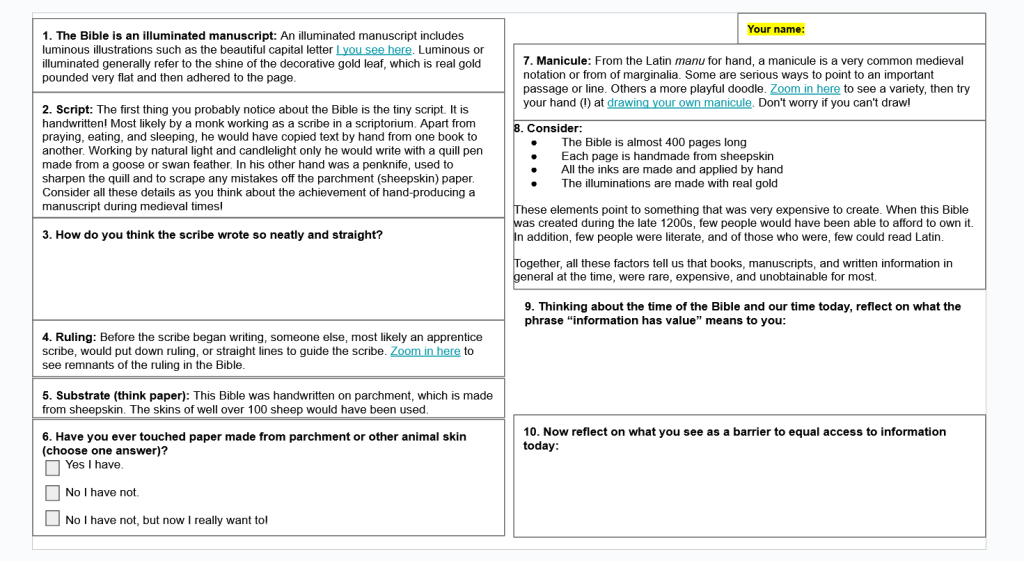

In terms of free platforms, my primary recommendation is Google Slides, as I use it for other instructional purposes.[11] On the slides, you can provide students with information, instructions, links. There is also space for their name and to answer questions.[12] I have created a sample adaptation of the Biblia Latina tutorial to demonstrate one possible approach:

Next, duplicate your template slide based on the number of students in a class. Each student completes their own slide. You and/or the instructor can review or grade them. Students can also see one another’s work, but it will be very obvious if they try to copy one another. Another perhaps more robust option is to use Google Forms to mimic the LibWizard quiz format a bit more closely.[13] Ultimately, you can use any tool or platform you like and that you have access to and support for. What matters is creating a means to achieve your learning objectives in a manner that is asynchronous and as interactive as possible.

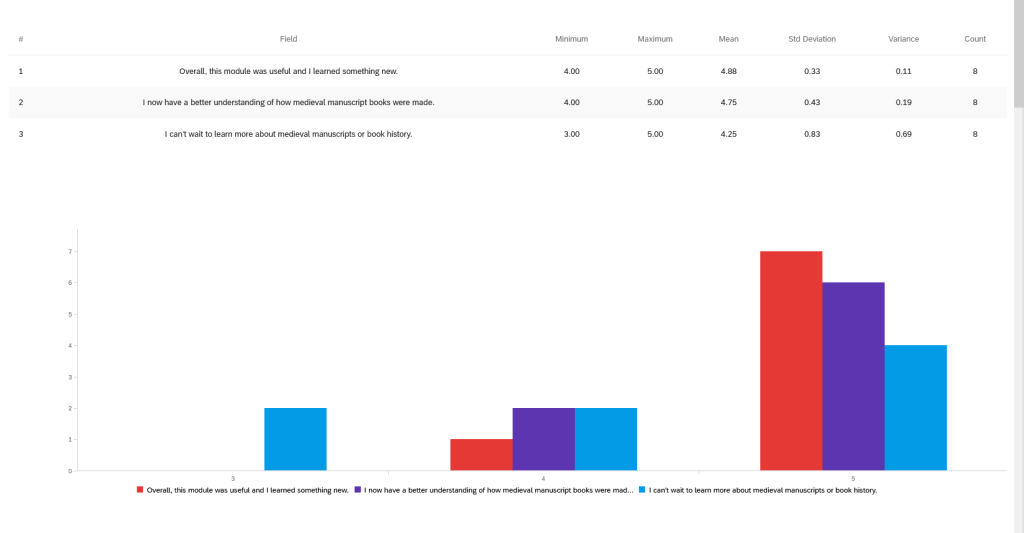

The final element of my tutorial is a link to a Qualtrics survey. Responses are anonymous and students are encouraged to provide honest feedback. The survey is not required and only about 25% of those who have completed the tutorial have also responded to the survey. Nonetheless, I value every response I receive and take any comments into serious consideration. Thus far the feedback has been very positive and encouraging.

One theme that is repeated is how much students appreciate and respond to the interactivity. One wrote, “It was interactive so it didn’t get boring.” From another, “It was interesting and also kept my attention.” A third comment reads, “It was helpful and interactive which helped me retain the information better than simply reading about it or watching a video.” Professor Shadis has also commented on this element, writing, “In my Western Civ class, which is a big lecture, and supplies a General Education credit to mostly non-majors, students consistently express appreciation for the interactive nature of the tutorial and simply to the exposure to the process of making medieval books.”[14] Given today’s short attention spans it is vital to find ways to engage students. This tutorial is achieving that goal, plus paving the way for deeper, more student-driven engagement in the classroom. As a result of its success, I intend to continue sharing the tutorial with faculty and working to edit and improve the content as needed for the foreseeable future.[15]

Endnotes

[1] Biblia Latina, France, late 13th century, Mahn Center for Archives & Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries, https://cdm15808.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/speccoll/id/1313/rec/2, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110195730/https://cdm15808.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/speccoll/id/1313/rec/2.

[2] Ohio University Libraries, The Millionth Volume, Athens, Ohio, 1979, Mahn Center for Archives & Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries, https://media.library.ohio.edu/digital/collection/archives/id/51420, archived January 12, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240112100411/https://media.library.ohio.edu/digital/collection/archives/id/51420 .

[3] Erin Wilson, email message to author, June 14, 2023.

[4] Miriam Intrator, “Biblia Latina / Latin Bible tutorial,” https://ohiou.libwizard.com/f/biblialatina, screenshot archived March 19, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250319191826/http://web.archive.org/screenshot/https://ohiou.libwizard.com/f/biblialatina.

[5] Select sources of guidance and inspiration early in the pandemic include, but are by no means limited to: RBMS virtual chat-TPS Community Call, Moving Archival and Special Collections Instruction Online, April 21, 2020; Dr. Jesse Strycker, “Creating and Using Instructional Videos, Screencasts, and Podcasts to Increase Instructor Presence, Increase Student Interaction, and Expedite Feedback in Online Courses,” Patton College of Education Remote Teaching Series, May 18, 2020; Teaching Strategies Virtual Workshop, Ohio State University, May 28, 2020; Dr. Jennifer Baumgartner, “Teaching Tools: Active Learning While Physically Distancing, Louisiana State University, July 15, 2020,” https://docs.google.com/document/d/15ZtTu2pmQRU_eC3gMccVhVwDR57PDs4uxlMB7Bs1os8/preview?pru=AAABcuIMyos*xO7bsUpf5LtQ5ZqoBky_tQ, archived June 15, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230615204755/https://docs.google.com/document/d/15ZtTu2pmQRU_eC3gMccVhVwDR57PDs4uxlMB7Bs1os8/preview?pru=AAABcuIMyos*xO7bsUpf5LtQ5ZqoBky_tQ.

[6] Miriam Shadis, email message to author, June 15, 2023.

[7] Association of College and Research Libraries, “Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education,” https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework, archived January 5, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240105080500/https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework.

[8] In late September 2023, Google announced that it will be sunsetting Jamboard by the end of 2024. Google is advising active users to migrate their content to one of their whiteboard partners, including FigJam, Lucidspart, and Miro. I will be doing so over summer 2023. Google, email to author, September 29, 2023.

[9] Miriam Intrator, “Manicule!,” https://www.figma.com/board/b9CHxIGLl6ItElE8kLc2OL/Manicules!?node-id=0-1&p=f&t=hAbVHdVL9yYmHkcH-0. The JamBoard created by students in the class was unable to be used because we needed permission from all of the students to use their designs. In its stead, the author asked colleagues to create manicules using the Figma FigJam whiteboard tool. Permission was obtained to use the new manicules.

[10] Miriam Shadis, email message to author, June 15, 2023.

[11] With thanks to Paul Campbell for the inspiration. Google Slides, https://www.google.com/slides/about/, archived April 30, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240430000624/https://www.google.com/slides/about/.

[12] Miriam Intrator, Biblia Latina / Latin Bible Google Slides tutorial adaptation sample, https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1ryW36tPrMhcZ_WOsFCt1KAWVSS4bBX5iOvvX_5y7HjM/edit?usp=sharing, screenshot archived March 28, 2025, at https://web.archive.org/web/20250328153502/http://web.archive.org/screenshot/https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1ryW36tPrMhcZ_WOsFCt1KAWVSS4bBX5iOvvX_5y7HjM.

[13] Google Forms, https://support.google.com/docs/answer/7032287?hl=en&visit_id=638173582308793184-248582401&rd=1#1.1, archived November 1, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231101160724/https://support.google.com/docs/answer/7032287?hl=en&visit_id=638173582308793184-248582401&rd=1#1.1.

[14] Miriam Shadis, email message to author, June 15, 2023.

[15] The tutorial is linked, along with others I and my colleagues created during the pandemic, on a LibGuide. Miriam Intrator, “Researching with Archival & Special Collections Primary Source Materials,” https://libguides.library.ohio.edu/archives-speccollections/forinstructors, archived June 25, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220625141744/https://libguides.library.ohio.edu/archives-speccollections/forinstructors.

Media Attributions

- Private: Document-1_Digitized-Bible-Spread © Ohio University Libraries is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Private: Document-2_Tutorial-Screenshot © Miriam Intrator is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Manicules! © Miriam Intrator is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Document-4_Google-Slide-Sample

- Private: Document-5_Qualtrics is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license