Lesson Plans

9 Imagined Libraries and Immersive Special Collections Instruction: A Visit to Enlightenment Britain

Laura Michelson and Allison Haack

Rethinking a special collections class visit for a History course on Enlightenment-era Britain sparked interest in a new approach to instruction in the Grinnell College Special Collections to create imagined libraries for students to explore. Considering the spaces and communities in which books were read, stored, and shared throughout the Eighteenth-century and collaboration with faculty led Special Collections instructors to reevaluate holdings used to represent the era and to create a new class structure. As an exercise in creative bibliography, ‘imagined libraries’ guided the creation of stations of books representative of historical libraries from the era. Over the course of a class session, students visited eight stations representing a circulating library, reading society, coffeehouse, private estate’s gentleman’s library, and scholarly libraries of science, botanical, and art societies. This immersive activity invited students to interact with books in imagined surrogates for the settings discussed in their coursework.

This chapter outlines an experimental hands-on session from its planning to implementation and takeaways. Through this approach of integrating rare books from the collection into imagined library spaces, students were invited to interact with and discover materials in a new way.

Special Collections at Grinnell College

Grinnell College is a private liberal arts college located in the small midwestern city of Grinnell. Home to approximately 1,750 students and with a student to faculty ratio of 9:1, the college is a rigorous and engaged community that is annually ranked as a top liberal arts and science college for academics and student body diversity. Grinnell College Special Collections and Archives holds a teaching collection totaling approximately 14,000 books and manuscripts; it is home to an impressive rare book collection, including the recently acquired Salisbury House Library Collection and rare holdings from the twelfth century to contemporary artist books. It also holds the college archives, which include materials documenting the people, events, and activities that have shaped the college since its founding in 1846. It is staffed by two full time positions—a Special Collections Librarian and Archivist of the College (Faculty line) and Library Special Collections and Archives Assistant (Staff line). A term faculty Project Archivist was a part of the SCA team from 2020-2024.

Special Collections and Archives (SCA) collaborates with faculty to host class visits and foster student learning using primary resources. Interest in integrating SCA visits and materials into the curriculum continues to grow at Grinnell. The number of class requests continues to grow, nearly doubling in 2022 from pre-COVID 2019. Typically, faculty reach out to SCA to schedule a class visit. Sometimes, this is in advance of the semester as they finalize their syllabus, but often this contact takes place as the semester is underway and the visit is an addition to the course. SCA staff also actively reach out to connect with faculty who visit with regularly offered courses and faculty teaching new courses for which SCA holds relevant materials.

The style of class visit varies and is tailored to class topic, student level, particular assignments and skill building, and staffing capacity—some class visits consist of a short (less than 30 minutes) drop-in to browse curated materials or a specific item; other courses attend for an entire class session (50 minutes or 110 minutes) and range in formats from ‘illustrated lecture’ led by their professor, embedded research sessions, show and tells, or other formats. The activity and format outlined in this chapter was the first of its kind at Grinnell.

Session Design and Set Up

In the fall of 2021, a History professor scheduled a Special Collections visit for their course HIS 235: Britain in the Age of Enlightenment. There were twenty-six enrolled students, making it one of the larger class sizes at Grinnell. Inspired by the course topic and pre-existing discussion on reading communities and learning spaces, we created eight stations representing a range of private and public libraries and spaces in which books were found and used in the era. An early concern was accommodating a class of this size with the desire for a more elaborate setup in limited space. To accommodate eight stations, we needed to expand beyond our Reading Room into the neighboring Print and Drawing Study Room (PDSR) space, connected through an adjoining door and with whom we frequently collaborate. Our Reading Room contains two tables, one with six chairs and one with eight. The shorter table was designated one station, while the larger table was split into two. We moved the reference desk into a corner and borrowed two narrow tables from the conference room across the hallway to create a fourth station in the Reading Room. The PDSR has a slightly larger space, with a large static table in the middle of the room, smaller mobile square tables, and a gallery wall. Each side of the long static table was designated as a station, the gallery wall was another station, and two square tables made up a third station in that room.

In the design of this approach, we were able to make creative use of not only our combined spaces and collections but also expertise and research interests. While none of our collections team are Enlightenment scholars, previous work and research helped inform this project. One of our team has worked extensively with a collection featuring the English Romantics, and another is knowledgeable about Victorian book culture. Having a cursory scope of the long eighteenth-century and familiarity with subgenres feeding or fed by this time was an asset, as was a united interest in collection history, historical book markets, and dedication to creating interactive and immersive pedagogy. Being curious and excited to research alongside this project was invaluable, everything from researching coffee shop history to browsing digitized records of historical libraries and locating historical illustrations of these spaces. A source that was instrumental in the design of this activity was William St Clair’s The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period1. Our collaborator in the Print, Drawing, and Study Room and her professional expertise in art history enriched this experience by pairing art with book materials. One apt discovery that helped meld collections was that William Hogarth—English satirist, engraver, and cartoonist whose art illustrated many scenes of life in Eighteenth-century England—spent years of his youth in his father’s unsuccessful coffee house, whose financial ruin led to imprisonment for debt.

Relying on the expertise of the professor teaching this course, our research and knowledge, and the review of our holdings, eight stations were created to bring Enlightenment-era libraries to life, framed as the Royal Society Library (a scientific society); Oxford Botanical Garden; Lloyd’s Coffeehouse; Lane’s Circulating Library (lending library); Temple of the Muses (bookshop); Burling Book Society (a reading society); the Royal Academy of Arts (arts society); and Alnwick Castle Library (country estate/private library).

Selecting materials proved to be a challenge in selection and exploration. While the long Eighteenth-century is well represented in existing holdings, no subject guide existed to guide selection. For cataloged materials, filtering by date range helped significantly to identify editions of particular authors or subjects. With a newly acquired collection being cataloged, a date audit created a list of works circa 1680-1835, totaling over 200 titles from which standout materials were highlighted and assigned to an appropriate ‘living library.’ Shelf reading was also helpful in locating appropriate materials. Factors in selection went beyond publication date and British origins—provenance, traces of past use, bookseller stickers, original price tags, fine or historical bindings, and other distinguishing features were taken into account. Some material at the imagined Temple of Muses bookshop station had original prices intact. At the Royal Society Library, we set out works by Charles Darwin, Isaac Newton, Archimedes, and Captain James Cook, representing scholars and explorers financed by the Society and earlier foundational scientific and mathematic texts. The lending library featured a variety of histories and popular literature, such as A Treatise on the Art of Dancing, Lara and Jacqueline, a Tale, and The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. Included in selections were books pre-dating the long eighteenth-century to encourage students to consider the various eras through which historical books have been read and survived, such as a medieval book of hours, which we imagined on the shelves of our estate library station and sixteenth century materia medica at the botanic society. Earlier texts were foundations for the Enlightenment, just as these texts influenced generations of books to come. Books or artwork were placed at each station, with selections based on the types of materials that would have been found in their real-life counterparts. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of materials utilized at each station.

The Classroom Session

When students arrive for a class session at Special Collections and Archives, they are asked to wash their hands and the group is given an introduction to usage policies and how to handle materials. For this class, we also gave an overview of the station layouts and instructed students to select a station to begin where they would spend the majority of their time. Because this class met for fifty minutes and the students had a large amount of material to examine in a short time, we decided to have students remain at one station for most of the class. We spent the last fifteen minutes on a group overview and then the students were free to explore the additional stations.

To differentiate the libraries and contextualize the selections, an informational sign was created for each station that included information about the historical location, its founding, address, mission or purpose, and the types of books, newspapers, or artworks. We asked the students to get to know the materials at their station and develop questions. Each station also included three reading questions and points for discussion.

READING QUESTIONS AND POINTS FOR DISCUSSION

- How would these books have been used in this space in the world of Enlightenment Britain? Who would be using them?

- How would you describe the types of books in this space? (Genre, content, intended use or audience, etc.)

- Can you think of other books (genre, authors, or titles) that would be appropriate additions to this library?

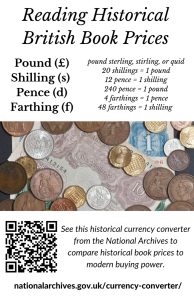

Students were asked to get to know the imagined library or collection, interact with classmates at their station, and then introduce their collection to the wider class during the group overview at the end of class. Cell phones and laptops were encouraged to look up book titles and authors. QR codes to online currency converters were also provided and were mainly used at the bookshop station to explore the modern cost of original book prices. Copies of the station sheets and conversion guides are included in Appendix 2 and 3.

Students were invited to make connections between books on an imagined library shelf in a new way, from the new books produced in the Enlightenment era to earlier tomes incorporated into the era’s libraries. At each station, a selection of books was laid out on book supports, some of the larger libraries including a shelfscape supported by bookends from which more books could be pulled and explored. Uniting books from Special Collections with related Grinnell Museum of Art materials from our neighbors in the Print and Drawing Study Room, books and art melded for aesthetic storytelling to provide historical context and touchpoints to class topics. Session deliverables came through students considering book use and readership, the historical cost of materials and the era’s book market, and the active communities of historical readers in a new light.

A longer class session or repetition of this visit would be ideal. After our condensed session, several students stayed after class for up to a half-hour close reading material. Investing preparation and creative design time into preparing for an immersive class session would be best suited for a longer or subsequent visit(s) and to be replicated and refined in years to come. We recommend considering the scope and scale of your need, focusing on one or two imagined libraries, creating a more directed activity or looking exercise with particular books, and bringing creative bibliography to your researchers.

Reflection and Future Implementation

Overall, this class visit successfully fostered an immersive experience with special collections holdings. It challenged students to engage with history and their class topics through a hands-on approach. It also served as a foray into our internal pedagogy and creative bibliography. Currently, we have no formal means of assessing instructional visits or documenting student or faculty feedback after a visit. However, we are cognizant of student engagement during a session. Students in this course were enthusiastic about handling materials and using the provided guides to interact with and contextualize book costs and dates. In discussion at the close of the session, students articulated connections between the stations they visited and individual items to course topics. Preparing for this course visit and discussion, we anticipated questions that were raised in discussion, affirming that students were thinking critically and that we were equipped to answer questions about book production and readership for the time period. At the close of the session, we invited students to stay longer if they would like to spend more time with the materials—a number of students stayed beyond the end of the session, one student staying nearly half an hour to finish reading a chapter in a novel at the Reading Society station. After the class, we received inquiries about student employment from a class attendee who has become an excellent addition to student staff! We also received positive feedback and appreciation from our faculty partner and interest in incorporating more immersive sessions into his courses. In future implementations, we plan to incorporate a formal assessment component into this and other instruction sessions.

This creative approach was implemented again in the Fall of 2023 as an example instruction session in a faculty pedagogy workshop hosted in SCA and in impacting the design and interactive sessions of a book history English course with work and learning embedded with SCA and recurring visits. Exploring and designing this immersive session has opened the door to new modes of practice and pedagogy and pushed our teaching team to be creative in implementing creative pedagogy in our work.

Consciously curating a selection of materials around an imagined library proves highly adaptable. While this course visit and reflection is grounded in a foray into the long eighteenth-century and Enlightenment Britain, this exercise in creative and experiential bibliography opens the door to explore collections through a new lens and craft a creative approach to forge new connections and ways to interact with the material to create immersive classroom experiences. In exploring books in the age of British Enlightenment, future stations to explore were also discovered. With our holdings, other settings for imagined libraries we look forward to exploring are exemplars from early printing, scholars’ libraries, and much more, as well as applying this practical approach to unite materials for interpretation in not only imagined libraries but also visualizing connections between materials from the same collector.

The imagined library structure is adaptable with infinite creative applications—to visualize not only imagined libraries, but collections from collectors in situ on a shelf or to collate materials inspired by fictional characters. It may be a tool for training for bibliographic practice, collection exploration, creative curation, and interpretation to conceive the connections between books on a library shelf, an object’s provenance and the previous environments they have inhabited, traces of past use, and the generations of hands they’ve passed through. As a longer project, this could be a flipped activity where students explore holdings and create their imagined libraries. This approach is well suited for creating a public event or open house beyond the classroom. Student experts could assist an event by introducing visitors to an imagined library they’ve studied or created and acting as a docent.

Provided in the appendices are examples of a pull list for this session, station sheets, and conversion resource sheets. The authors are pleased to connect and chat—contact us at archives@grinnell.edu.

APPENDIX 1

Imagined Libraries Titles Pull List | Grinnell College Special Collections

Royal Society Library

Archimedes. Opera nonnula. Venice: Aldine Press, 1558.

Darwin, Charles. On the origin of the species by means of natural selection : or, The preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: J Murray, 1859.

Grew, Nehemiah. Anatomy of Plants: With an idea of a philosophical history of plants. And several other lectures, read before the Royal Society. London: Printed by W. Rawlins, for the author, 1682.

Guthrie, William. A New System of Modern Geography. Philadelphia : M. Carey, 1786.

Newton, Isaac. Arithmetica universalis ; sive de compositione et resolutione arithmetica liber. London: Impensis Benj., 1722.

Royal Society. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London: W. Bowyer and J. Nichols for Lockyer Davis, printer to the Royal Society, 1779-1886.

Struys, Jan Janszoon. Les voyages de Jean Struys. Amsterdam: Chés la Veuve de Jacob van Meurs, 1681.

Walter, Richard. A Voyage round the world: in the years MDCCXL, I, II, III, IV. London: Printed for the author by John and Paul Knapton, 1748.

Alternative titles:

Archimedes, Eutocius. Archimedis opera non nulla. Venice: Apud Paulum Manutium, Aldine Press, 1558.

Britton, John. Beauties of Wiltshire, Displayed in Statistical, Historical, and Descriptive Sketches. London: Printed by J.D. Dewick for Vernor and Hood, 1801.

Cudworth, Ralph. True intellectual system of the Universe, second edition. London: printed for J. Walthoe, D. Midwinter, J. and J. Bonwick, W. Innys, R. Ware [and 17 others in London], 1743.

Newton, Isaac. Opticks, or, A treatise of the reflexions, refractions, inflexions and colours of light : also two treatises of the species and magnitude of curvilinear figures. London: Printed for Sam. Smith, and Benj. Walford, 1704.

Sale, George, George Psalmanazar, Archibald Bower, and Beilby Porteus. The modern part of an universal history from the earliest account of Time: Compiled from original writers. London: printed for S. Richardson, T. Osborne, C. Hitch, A. Millar, John Rivington, S. Crowder, P. Davey and B. Law, T. Longman, and C. Ware, 1759.

Botanical garden

Aiton, William. Hortus kewensis; or, a catalogue of the plants cultivated in the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew. London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1810-1813.

Darwin, Erasmus. The Botanical Garden: A poem, in two parts: Part I. Containing The economy of vegetation: Part II. The loves of the plants: With philosophical notes. London: J. Johnson, 1795.

Evelyn, John. Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest Trees. London: Printed by J. Martyn, and J. Allestry, printers to the Royal Society, 1664.

Lyte, Henry. A new Herball, or Historie of Plants. London: Edm. Bollifant, 1595.

Mattioli, Pietro Andrea, Des Jean Moulins, Guillaume Rouillé, and Dioscorides Pedanius. Commentaires. À Lyon: Par Guill. Roville, 1579.

Coffeehouse

Rare Pamphlets including The Beggar’s Opera; Dempster’s Original Ballad Soirees; The Moral Almanac, for the Year 1846; Thomas Hardy, Notes on His Life and Work; The Butler Collection I, II, and III; Colonel R.G. Ingersoll’s New Lecture: Voltaire; A Daring Adventure. London: assorted publishers, 1837-1847.

Hogarth, William and John Trusler. Hogarth Moralized, a Complete Edition of all the Most Capital and Admired Works of William Hogarth. London: Printed at the Shakespeare Press, by W. Nicol, for John Major, 1831.

Lee, Arthur, John Almon, William Smith Mason. Appeal to the Justice and Interests of the People of Great Britain. London: Printed for J. Almon, 1776.

Price, Richard. Observations on the nature of civil liberty : the principles of government, and the justice and policy of the war with America. London: Printed for T. Cadell, 1776.

Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. The Saturday Magazine, Volume 1 July – December 1832.

United States, Thomas Jefferson, George Hammond. Papers Relative to Great Britain. Philadelphia: Printed by Childs and Swaine, 1793.

Alternative titles:

Clarkson, Thomas. The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament. London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1808.

Great Britain, John Almon, George St. Amand. A Complete Collection of the Lords’ Protests. London: 1767.

An Original Issue of “The Spectator” (one original leaf modern text) | 1717 in 1939 publication.

Paired with Museum of Art collection materials on display including Hogarth and scenes of city life, public houses, etc.

Lending Library

Abelard, Peter and Heloise. Letters of Abelard and Heloise. London: Printed for Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1815.

Collier, Jane. An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting; with proper rules for the exercise of that amusing study. London: Millar, 1806.

Gallini, Giovanni-Andrea. A Treatise on the Art of Dancing. Printed for the author and sold by R. Dodsley, London, 1772.

Rogers, Samuel and John Davis Batchelder. Lara and Jacqueline, a Tale. London: Printed for J. Murray, 1814.

Russell, Rachel, Thomas Sellwood, William Russell. Letters of Lady Rachel Russell : from the manuscript in the library at Woburn Abbey. London: Printed J. M’Creery for J. Mawman, J. Walker, Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, Lackington, Allen and Co., Darton and Harvey, R. Lea, B. Crosby and Co., J. Booker, J. Murray, R. Scholey, and J. Cawthorn, London, 1809.

Williams, T. The Accomplished Housekeeper and universal cook. London: Printed for J. Scatcherd, 1797.

Ideas for future additions:

Contemporary novels, particularly gothic novels. Lesser known contemporary novels would be particularly appropriate because this era of reading saw a boom of fiction with small print runs, some never reprinted.

Bookshop

Bacon, Francis. History of Henry VII of England : written in the year 1616. Printed for the editor, at the Logographic Press, by The Literary Society, 1786.

Berkeley, George. A miscellany: containing several tracts on various subjects. London: Printed for J. and R. Tonson etc., 1752.

Combe, William. Third Tour of Doctor Syntax, in search of a Wife, a poem. London: Published at R. Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, 1821.

De Quincey, Thomas. Confessions of an opium-eater. London: Taylor and Hessey, 1822. [Notable for this item was inclusion of an original bookshop price tag and 19th century blue paper boards.]

Hood, Thomas. The Dream of Eugene Aram, the Murderer. London: Charles Tilt, 1831. Boundwith Robert Burns’ Address to the Devil and Tam O’Shanter and the Children of the Wood ballad.

Sterne, Laurence. A sentimental journey through France and Italy. London: Printed for T. Becket and P. A. De Hondt, 1768.

Ideas for future additions:

Novels published anonymously “By a Lady,” in particular gothic romances.

Reading Society

Brunton, Mary. Self Control: A Novel. Philadelphia: Farrand, Hopkins and Zantzingerr, 1811.

Edgeworth, Maria. Moral Tales for Young People. New York: W.B. Gilley, 1819.

Fletcher, John. The Test of a New Creature, or heads of examination of adult Christians. 1805

Gay, John. Fables, Moral and Political on Various Subjects. Dublin: Printed by William Porter, 1804.

Walker. Female Beauty, as preserved and improved by Regimen, Cleanliness and Dress. London: T. Hurst, 1837.

Mirth in ridicule or, a satyr against immoderate laughing. London: Printed: and sold by J. Morphew, 1708.

Thompson, James. Seasons [book of poems, edition lacking title page identification]. circa 1730-1820.

Gallery / Art Society

Ackerman, Rudolph (editor). The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufacturers, Fashions and Politics. Volumes 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 1810-1813.

James, John Thomas. Italian Schools of Painting with Observations on the Present State of Art. London: J. Murray, 1820.

Sutherland, George Granville Leveson-Gower and John Young. A Catalogue of the Collection of Pictures of the Most Noble the Marquess of Stafford at Cleveland House, London, containing an etching of every picture, and accompanied with historical and biographical notices. London: Hurst, Robinson, and Co., 1825.

Van Veen, Otto. Q. Horati Flacci Emblemata [hand tinted emblem book]. Antwerp: [1670].

Paired with art materials from the art collection: J.M.W. Turner and Turner school prints.

Country Estate / Private Library

15th century [illuminated book of hours], uncatalogued.

Egan, Pierce, Henry Thomas Alken, and Henry Ward. Real life in London, or, The rambles and adventures of Bob Tallyho, Esq. and his cousin, the Hon. Tom Dashall, through the metropolis: Exhibiting a living picture of fashionable characters, manners, and amusements in high and low life. London: Printed for Jones and Co., Warwick Square, Newgate Street, 1821.

Lamb, Charles. The Book of the ranks and dignities of British society : chiefly intended for the instruction of young persons. London: Printe for Tabart & Co., 1805.

Poynder, John and John Charles Dallas. A History of the Jesuits; to which is prefixed A reply to Mr. Dallas’s Defence of that Order. London: Printed for Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1816.

Topsell, Edward. The Historie of Foure-footed Beastes. London: Printed by William Iaggard, 1607.

Scott, Walter. Lay of the Last Minstrel., a poem. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1812.

Alternative titles:

Collins, Arthur. The Peerage of England Containing a Genealogical and Historical Account of all the Peers of England. London: printed for W. Innys and J. Richardson, T. Wotton and E. Withers, C. Hitch and L. Hawes, R. Manby, J. and J. Rivington, H.S. Cox, W. Johnston, P. Davey and B. Law, 1756.

Pomey. Francois. The Pantheon Representing the Fabulous Histories of the Heathen Gods, and Most Illustrious Heroes. London: printed for C. Bathurst, J. Rivington, L. Hawes and Co. S. Crowder, B. Law [and 4 others, 1774.

Sterne, Laurence. The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy, a Gentleman. London: Pall-Mall. 1760.

Corbould, Edward Henry. The Eglinton Tournament. London: Hodgson & Graves, 1840.

APPENDIX 2

Background Information and Questions for Each Station

Royal Society Library | Inspiration for a station hosting books of science, the natural world, and expeditions, including some books sponsored by this organization and influential works predating the long-Eighteenth century included. Inspiration from a digitized catalog available online including some donations from the Seventeenth/Eighteenth century but lacking the Mss and book lists. The original library is yet maintained today.

Library of the Oxford Botanic Garden | Inspired by the existing Oxford Physic (Botanic) Garden established in 1621, the Chelsea Physic Garden established in 1673, and other botanical societies at a height in the Enlightenment. This station includes books on botany, trees, flora, and herbals including some older volumes which would have been foundational reference texts.

Burling Book Society | A fictional book society created to represent a moralized community of books and readers, inspired by the Greenock Book Society, Chawton Book Society, and Ayr Library Society. Book list includes ‘moral’ fiction, religious texts, books on conduct and society.

Alnwick Castle Library | A representative estate or ‘gentleman’s library’–grand example of a privately owned library. Particularly fine bindings and special editions, medieval manuscripts, etc.

Lane’s Circulating Library | A lending library based on the historic Lane’s Circulating Library of London, established in 1774. A circulating library targeting middle class readers with popular books, particularly novels.

Temple of the Muses | Modeling the commerce of books and boom of bookstores during the long Eighteenth Century and the historic Temple of Muses, a London bookstore which opened in 1794. Materials at this section included original prices on title pages or spines.

Lloyd’s Coffee House | Inspired by the historical Tower Street coffee house which was frequented by merchants and maritime workers. This library station features newspapers and magazines as well as works illustrated by William Hogarth, whose art depicts many scenes of coffee houses and working-class England who frequented coffee houses as centers for discourse.

Royal Academy of the Arts Library | Representing art societies and schools of the era and inspired by the historic Royal Academy and galleries. Historic and contemporary art materials including catalog of art collections, artist reference texts, and a magazine of arts, fashion, and furnishings from the era.

Each station was illustrated with a historical image and the same reading question prompts:

Reading Questions Points for Discussion

Get to know selections from this library. What questions do you have about them?

- How would these books have been used in this space in the world of Enlightenment Britain? Who would be using them?

- How would you describe the types of books in this space? (Genre, content, intended use or audience, etc.)

- Can you think of other books (genre, authors, or titles) that would be appropriate additions to this library?

Station Descriptions

Full station sheets will be provided on request—email us at archives@grinnell.edu for file requests.

Welcome to the Royal Society Library.

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge was established in 1660. The eminent Royal Society’s fundamental purpose is to recognize, promote, and support excellence in science and to encourage the development and use of science for the benefit of humanity. Society motto: Nullius in verba (take nobody’s word for it). The London society has been housed in Somerset House since 1780; in 1781 artifacts of significance were acquired by the British Museum, providing space for the society to expand the growing library to two rooms, including a meeting space. (In 1857 the Society would move to a wing in Burlington House. Today the society exists in Carlton House Terrace.)

Welcome to the library of the Oxford Botanic Garden.

The Oxford Physic (later, Botanic) Garden was established in 1621, the oldest botanic garden in Britain. It was followed by others, including the Chelsea Physic Garden established in 1673. These gardens were originally spaces of teaching and experimentation, cornerstones of the scientific Enlightenment. In 1834 Charles Daubney, a Professor of Botany at Oxford, made extensive changes to the gardens and buildings, including proposing a new greenhouse, lecture room, space for dried plants collections, and a library to rehouse books from professor’s study spaces. (Today the majority of this botanical garden’s library along with further decades of botanical research made possible by this resource and teaching at Oxford now reside in Bodleian Libraries, Oxford.)

Welcome to the Burling Book Society.

Communities of reading were found in book clubs or reading societies, which were created as alternatives to lending libraries. The Greenock Book Society stated their mission “to save themselves the expense of purchasing many books, and to avert the fatal effects which are sometimes occasioned by circulating libraries”—many people were avoiding the risqué reputation of lending libraries and salacious novels. Formed by communities of friends or neighbors, many societies were named for a location such as the Chawton Book Society, where Jane Austen was a member; named for their founder like Mr. Ridge’s Book Society; or self-descriptive, such as the Eclectic Book Society.

Some groups sought to continually grow memberships and holdings with the goal of establishing a permanent library in their community; others were intended to remain small and exclusive clubs. Catering to the merchant class, clergy, gentry, and nobility with disposable income, membership included men and women. Typical reading societies had between a dozen and two dozen members, some gendered or a mixed membership.

They differed from lending libraries in the accumulation of books, fee structures, and engagement amongst a community of readers. Members shared in the financing of building a small library collection–likely at a discount from booksellers–and once titles had circulated to all interested members, may have been retained for a permanent library, sold back to a seller, or bought at a reduced price by a member. The readership of a group would determine what titles were purchased.

Established in 1762, a Scottish reading society, the Ayr Library Society, held fees of a 1 shilling entry fee and 7 shillings annual fee; a committee selected book purchases four times a year. An unidentified book club based in London in 1822 records that twelve members met at each other’s homes four times a year to select books and had an annual income of 360 shillings plus 160 shillings from the sale of books. The fees and records of many smaller clubs have been lost along with their book lists which ranged from a few dozen titles into the thousands.

Welcome to the Alnwick Castle Library.

Alnwick Castle has been the home to the Percy family since 1309; it is the second oldest inhabited castle in England. The family was elevated to Earls by Richard II and then elevated to Dukes by King George III in 1766. The castle is the residence of the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland and in the spring and summer is open for tours to the general public as well as researchers. The expansive library houses nearly 15,000 books and occupies the entire first floor of a tower added during a 19th century renovation. The castle is also home to a Percy family archive and collections of paintings, furniture, and ceramics, as well as extensive gardens including a Taihaku Cherry Orchard, a Poison Garden, and a Rose Garden. Some private estates libraries of the Enlightenment have survived intact in their original homes, while others have been acquired by institutional libraries, or dispersed by sale.

Welcome to Lane’s Circulating Library.

Circulating libraries became popular in the mid- to late 19th century because the high price of books kept them inaccessible to most people. The aspiring middle class and those of more modest means could pay a fee to a circulating library in order to rent the newest and popular books, pamphlets, and magazines. The first circulating library in England opened in 1728; by 1801 there were nearly 1,000 in operation. Women were the majority of customers, largely of novels. Lane’s Circulating Library was established in London around 1774 by bookseller William Lane. In around 1790, Lane also opened the Minerva Press. It was common for publishers or book shops to own circulation libraries, and the Press printed nearly a third of all books printed in London. It was particularly known for printing sentimental and Gothic works of fiction written by women. Lane’s was a particularly large circulating library, offering around 20,000 books, many published by the Minerva Press.

FROM ST. CLAIR, Appendix 10 Libraries and reading societies[1]

London, late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Minerva Library, Leandenhall Street, London, founded 1775, early nineteenth century rates (shillings)

Eighteen books in town or twenty four in country 84

Twelve books in town, eighteen in country 63

Six books in town, twelve in country 42

Four books in town, eight in country 31.5

Two novels at a time 16

Non-subscribers, per volume per week: 0.5 folio 0.3 8vo 0.25 12mo 0.16 single plays

Welcome to The Temple of the Muses.

In 1794, bookseller James Lackington opened a large bookstore, called The Temple of the Muses, in London’s Finsbury Square. Lackington advertised that the bookstore was “The Cheapest Bookstore in the World” and many of his business practices – such as not accepting credit – were radical for the time. He bought large volumes of books and then sold them cheaply for cash. Unlike earlier bookstores, browsing and reading were encouraged. The Temple of the Muses boasted four floors and a shop front 140 feet long. It is believed that at its height of popularity, the store housed 500,000 books. In 1810, the store sold 100,000 volumes. The bookstore burned down in 1841.

Historical Currency Converter

Find out about purchasing power in various decades:

UK National Archives Currency Converter website

1757 – A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful, 3 shillings 1782 – Cecilia, Memoirs of an Heiress (5 volumes), 15 shillings

1813 – Pride and Prejudice (3 volumes), 18 shillings

1822 – Confessions of an English Opium Eater, 5 shillings

Welcome to Lloyd’s Coffee House.

Coffeehouses of Enlightenment Britain were venues for pamphlets and books to circulate, some with formal lending and others through the exchange of the communities that gathered there. As meeting places, they were frequented by political and social groups to meet informally or gather for meetings.

Lloyd’s Coffee House was established in February of 1688 on Tower Street in London by Edward Lloyd. The Coffee House catered to sailors, merchants (particularly those involved in shipping) and ship owners. Popular topics of discussion were foreign trade, shipbroking, and maritime insurance. Over the years, different papers were published by the coffee House, including Lloyd’s News, Lloyd’s List, and New Lloyd’s List. In particular, Lloyd’s List focused on shipping intelligence. The Society for the Registry of Shipping was founded in 1760 and for a time met at Lloyd’s Coffee House.

Welcome to the Royal Academy of Arts library.

The Royal Academy of Arts was founded in 1768 to promote the creation, enjoyment, and appreciation for the arts. It originated from the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, a group which formed in the 1750s. The Royal Academy gained royal patronage and little financial support to create an academy of design and art; this allotted freedom of operation. Originally occupying rooms in Pall Mall, the Academy moved in 1771 to Somerset House, then Trafalgar Square in 1837, and to Burlington House in 1868. The first president of the Academy was painter Joshua Reynolds. A space for instruction, support of artists, exhibitions, and a venue for lectures and debate. The Academy in its first year of instruction enrolled 77 students; by 1830 over 1,500 students enrolled in programs. Students included prominent artists like JMW Turner and William Blake–in 1860, Laura Herford was the first enrolled woman to attend the Academy. Classes were free of charge to admitted students. Admission fees to galleries for exhibitions and lectures provided income. During the Enlightenment, the Royal Academy was home to artists from various schools, most notably neoclassical, Romanticism, and pre-Raphaelite. The Academy holdings includes original works of art in its permanent collection as well as a sizeable library; this is the oldest institutional fine arts library in the UK.

APPENDIX 3 | CONVERSION GUIDES

Media Attributions

- Roman Numeral converter © Authors

- Reading Historical British Book Prices © Authors

- St. Clair, William. The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period. Cambridge, U.K. ; Cambridge University Press, 2004. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/samples/cam041/2003060795.html. The Appendix 10 we are referencing is pp. 665-675. ↵