Reference

1 Engaging with Nineteenth-Century Literary Periodicals

Maggie Gallup Kopp

Introducing the Literary Periodical

Nineteenth-century English literature courses tend to focus on the work of major novelists like Melville or the Brontës, or major poetic works like Whitman’s Leaves of Grass or Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads. Yet bound novels and poetry books made up only a small portion of the print material consumed by readers in the nineteenth-century United States and Great Britain. Instead, readers most frequently engaged with the contents of the many periodicals circulating in these countries: newspapers, magazines, and journals of various lengths and sizes which were published at intervals (as frequently as daily or weekly or in longer periods, for example, monthly or annually). Like today, periodicals circulated such timely content as the latest news, current fashions, cultural criticism, and scientific discoveries, but in the nineteenth century, periodicals were also the predominant method of publishing literary works. Poetry, short fiction, and even serialized, full-length novels regularly appeared in the pages of a wide range of periodicals, from local newspapers to nationally circulated magazines.

The first printed newspapers and magazines appeared in Europe in the seventeenth century; the first newspaper in the British Isles, the Oxford Gazette, began circulation in 1665. Periodicals grew in popularity throughout Great Britain and its American colonies during the eighteenth century and began to dominate the publishing landscape in Britain and the United States in the nineteenth century. Demand for newspapers and magazines was fostered by major social changes during the period, especially the spread of literacy through the lower and middle classes in the United States and Europe. Richard Altick used English and Welsh census figures, from the 1840s to 1900, to chart the growth of literacy to near-universal levels among men and women by the end of the nineteenth century.[1] The development of a true mass reading public created a new market for low-cost reading material.

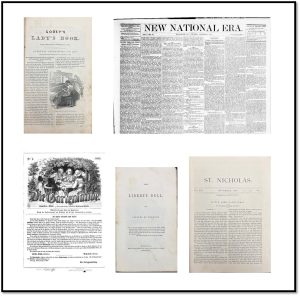

Figure 1 shows five American periodicals, showing a very small sample of the types of audiences for journals and newspapers. Clockwise from top right: New National Era, a weekly African-American newspaper owned by Frederick Douglass (image courtesy of Library of Congress; digitized volumes accessible at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026753/); St. Nicholas, a monthly children’s magazine (digitized volumes available at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000640805); The Liberty Bell, an annual abolitionist periodical (digitized volumes available at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008686573 or https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012242276); Die Gartenlaube, a German-language magazine for the immigrant community (image from Northwestern University via HathiTust; digitized volumes accessible at http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011920755); and the famous Godey’s Lady’s Book (digitized volumes accessible at https://archive.org/details/pub_godeys-magazine). All other images courtesy L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

In addition, the emergence of technologies like steam-powered printing presses (in the 1830s) and machine typesetting (in the 1880s) allowed print material to be produced quickly and cheaply.[2] Transportation innovations like the railroad facilitated a wider, faster distribution of print. Other time-saving technologies of the nineteenth century produced an increase in leisure time, particularly among the middle classes of British and American society, which in turn fed the ever-growing demand for reading material.[3]

Periodicals were usually cheap to produce, and cheap to buy. Books were too expensive for working- and middle-class readers to purchase regularly. British publishers in particular set prices for new literature quite high; for several decades of the nineteenth century, new novels cost a guinea and a half—more than the average working man’s weekly wage.[4] A newspaper or magazine, on the other hand, could be purchased for pennies.[5] As with modern periodicals, readers could subscribe to their favorite titles or purchase individual issues from retailers, including booksellers’ stalls in railway stations and coffee shops. It was also common for nineteenth-century readers to access periodicals through libraries (both public and private), and through association with groups like social clubs or mutual improvement societies, which stocked newspapers and magazines for members’ perusal.[6]

Publishers all over the US and Britain entered the market for periodicals, targeting readers of various social stations and catering to many interests. Periodicals were created specifically for women and children; for devotees of hobbies, sports, and other leisure pursuits; for various religious, political, geographical, or professional affiliations; and for members of specific economic classes or ethnicities (see Figure 1). Publishers and editors set the periodical’s tone and ideological stance, which might change perceptibly with the arrival of new proprietors or a decision to shift the periodical’s target market. One such change was evident when the American periodical Scribner’s Monthly Magazine was renamed The Century Magazine after being sold to a new owner in 1881.[7] Another example is the British monthly periodical The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, first published in 1852 .[8] It initially began life as a cheap publication for middle-class women, offering practical domestic instruction and information about current fashions. In 1865, the publisher shifted the magazine to a larger format, with colored fashion plates imported from Paris and a higher price point, directed at a more affluent readership (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 shows a side-by-side comparison of two volumes of The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, from 1854 (vol. 2) and 1873 (third series, vol. 14–15). Volumes at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University. Digitized copies of these volumes can be found at https://archive.org/details/pub_englishwomans-domestic-magazine.

The huge number of periodicals published on both sides of the Atlantic provided a fertile market for authors. While some writers chafed at the constraints of the periodical format as compared to the long form book format, journals and magazines offered authors the ability to produce content on timely topics, and provided more opportunities for women and amateur writers to publish poetry, fiction, and nonfiction.[9]

Fiction and poetry were published in many types of periodicals. Titles such as Scribner’s Monthly or the English periodical The Cornhill[10] maintained a sophisticated literary tone, predominantly featuring essays, short fiction, and serialized long form fiction. Other titles, like those run by religious or educational charities, specialized in more didactic or moralistic literature and numerous cheap publications—usually aimed at working class readers—specialized in lowbrow, sensational fare. Even newspapers, though focused on current affairs, published poems, lyrics, and fiction. Most periodicals intermingled literary pieces with journalistic or informational content. For example, the 1873 volume of the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine in Figure 2 contains a serialized novel along with articles dedicated to the latest fashions, biographies of famous women, household hints, and participatory reader correspondence columns, among other features.

Writers of short fiction might be paid by the page or by the piece, and typically did not retain copyright over their work. Poetry was less likely to be compensated, particularly the sorts of poems submitted to local newspapers, but some poets were able to leverage the popularity of their periodical poems into books. As writers became more established and popular, they could receive higher compensation,[11] and might receive requests for submissions from the editors of major periodicals. For example, Louisa May Alcott frequently submitted poems, travel sketches, and sensational stories to newspapers and magazines before achieving fame with her novel Little Women. One of her earliest stories, “The Rival Prima Donnas,” was sold for five dollars to the Saturday Evening Gazette in 1854.[12] Her later pseudonymous thrillers of the 1860s commanded as much as one hundred dollars.[13] After Little Women, editors of major American children’s magazines like Merry’s Museum, The Youth’s Companion, and St. Nicholas solicited short and serial fiction from Alcott, with proposals of much larger payments. The Youth’s Companion editor Daniel Ford offered her seven hundred dollars to write a temperance-themed tale for his magazine. Alcott obliged with “Silver Pitchers,” which appeared in six weekly installments in May–June 1875.[14]

Authors in various genres could also leverage their writing success into paid positions with journals and newspapers, including as a regular columnist, critic, or even as editor.[15] English author G. H. Lewes remarked in 1847 that “to periodical literature we owe the possibility of authorship as a profession.” In England, he explained,

It is by our reviews, magazines, and journals, that the vast majority of professional authors earn their bread; and the astonishing mass of talent and energy which is thus thrown into periodical literature is not only quite unexampled abroad, but is, of course, owing to the certainty of moderate yet, on the whole, sufficient remuneration.[16]

Using Nineteenth-Century Periodicals in the Classroom

Over the past decade, periodical studies have become a robust field of inquiry, particularly in the field of British literature. Given their ubiquitous but often overlooked place in the publishing landscape of the nineteenth century, periodicals are useful primary sources for students to engage with the period’s literature and culture in its original context. Nineteenth-century periodical literature is very accessible. Copies of popular titles like Godey’s Lady’s Book, The Atlantic, or Household Words can still be found in many academic library print collections. Digital surrogates of nineteenth-century periodicals can also be accessed through public domain digitization, such as the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America project (https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov), HathiTrust Digital Library (https://www.hathitrust.org), Internet Archive (https://archive.org), or through library subscription databases like Gale’s Nineteenth Century Collections package and ProQuest’s Historical Newspapers. The University of Pennsylvania Libraries’ Online Books Page (https://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/) also links to many free digitized periodical resources by title and volume. My current institution has a strong collection of physical sources which I use in hands-on primary source instruction, but I also opt to introduce digitized sources in order to support student learning activities or class assignments. Digital surrogates are often more accessible for students and may offer features like full-text searching which are advantageous for some assignments.

While students may be comfortable reading modern magazines in both analog and digital formats, instructors should be aware that nineteenth-century periodicals and their digital surrogates can pose a few stumbling blocks for novice users. Many copies preserved in institutional collections exist as bound volumes of collected issues, which usually lack wrappers and supplemental material such as loose plates and special inserts. Some of these volumes were created by publishers from six months’ or a year’s worth of extra sheets, given a table of contents, and sold as a collected volume. Other volumes were assembled from subscription copies, which might be missing issues, or might not be bound in the volume sequence established by the publisher. It can be difficult to notice when periodical content is missing or misbound, both in physical copies and in digital surrogates, without paying careful attention to page numbering, tables of contents, and the text of the periodicals.

Another challenge for students can be finding citation information in periodicals. In practice, some periodical publishers were inconsistent with volume and page numbering. A change in editor or format might prompt a publisher to begin a new series of volume numbering (in figure 2, the 1873 copy of Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine is labeled as a volume in the “third series” by the publisher, meaning the title had been reset to volume 1 more than once). Some titles might begin each new issue with page number 1; other titles might number all pages in a volume consecutively, beginning a new pagination sequence with a new volume. These paratextual features can be confusing for students, particularly when encountering periodicals in a digital form, since some platforms only present one page image at a time, or might only present the page snippet corresponding to a poem or article. Students may need to be instructed how to navigate a given platform to find volume, issue, and page number information needed for referencing in papers and other projects.

The following is a sample lesson plan, including an icebreaker activity, to introduce English and American literature students to nineteenth-century literary periodicals. It includes several discussion prompts and instructional activities which can be adapted to suit different learning objectives. In my own primary source instructional practice, I use original or digitized nineteenth-century periodicals with literary content to support several literature and humanities classes with different learning objectives, including:

- Examining canonical nineteenth-century texts and/or authors in their original publication context

- Recovering and studying middlebrow, non-canonical literature (short fiction, poetry, children’s literature)

- Analyzing the impact of illustration and advertising on nineteenth-century literature, mass media, fashion, or visual culture

- Studying the development of mass readership and issues of literary taste and reception

- Considering the impact of serialization on literary production and authorial practice

I typically start instruction sessions with an icebreaker, handing out loose issues of contemporary periodicals and asking students to share their observations. Students are used to judging the intended audience of modern magazines by examining both the contents and the physical characteristics of individual issues or volumes. For example, the typography, layout, page count, and paper quality may all provide clues about whether a particular periodical is a deluxe or cheap production; the presence, size, and quality of illustrations, photographs, and advertisements may also hint at a periodical’s editorial stance and target market. I then introduce nineteenth-century periodicals in bound volumes and loose issues and ask the students to analyze the older sources using the same methods.

Materials and lecture and discussion prompts in this sample lesson plan can be adapted to support course topics and learning goals. For a course studying nineteenth-century novels, I would select periodical titles which contain serialized novels by both well-known and lesser-known authors and would incorporate a discussion of seriality and serial publication into the class session. For a course focused on short fiction or poetry, I would likely discuss publishing strategies for authors, including anonymous publication, and I would select newspapers and magazines from different periods, regions, and price points to demonstrate the wide variety of periodicals available to nineteenth-century readers. For a class assignment to recover and/or edit content from nineteenth-century periodicals, I would shorten the lecture portion and spend more time demonstrating library catalog and database searching.

The sample lesson plan also describes two brief “case studies” of British literary works which were discernibly shaped by the process of being published in a periodical setting. These case studies are anecdotes I might share when discussing the process of publishing and editing material for periodicals, particularly how editorial intervention and the periodical format might shape the creation and interpretation of a text.

Sample Lesson Plan

Potential Lesson Objectives

- Students will be able to analyze textual and paratextual information embedded in nineteenth-century periodicals

- Students will be able to identify primary source texts in nineteenth-century periodicals

- Students will begin to formulate research questions about nineteenth-century periodicals as primary sources

- Students will be able to discover this material using library search tools and/or databases

Materials to Prepare

- Current periodical issues (select various titles and genres, including popular titles. One issue for each student or for a pair of students)

- Nineteenth-century periodical volumes/issues as available for each student or for pairs/small groups, or select digital sources in advance to show class on screen. For the accompanying case studies, prepare:

- Worksheets with discussion prompts and/or handouts with URLS and library resources, if desired

Lesson Components

- Opening activity: Distribute current periodicals. Give the students 2–3 minutes to browse.

Discussion prompt: Without looking at the text of the articles, what can you tell about the intended audience for the periodical? (Suggest such features as number of pages, paper quality, advertisements, use of color, illustrations or photographs, and graphic design elements.)

What else can you tell about this journal just from looking at the physical volume? (Point out genres, publishers, circulation, or anything else that might be relevant.)

- Lecture components (adapt as needed): The nineteenth century saw a huge increase in publishing periodicals, with rising literacy and leisure time and the development of mass readership. As is common today, periodicals were produced for different audiences and interests. Periodicals were highly affordable compared to novels and books of poetry; most readers were more likely to consume literary content through magazines and newspapers rather than monographs. What is a serial? How does seriality affect the composition, publication, and consumption of a text? Why might an author decide to publish in a given periodical?

- Activity and discussion: Distribute nineteenth-century periodical volumes (or help students navigate to digitized volumes). Potential discussion prompts:

- What can you tell about this journal just from looking at the physical/digital volume?

- What can you infer about the audience of this periodical based on textual or non-textual contents?

- What other content did you find besides literature? Does it relate to the literary content?

- What is your experience of consuming literature in these periodicals? How does it differ from reading a standalone novel, or content in your textbook?

- Library tools and finding periodicals in library collections and databases. Potential topics:

-

- Demonstrate how to read a serial record to identify coverage of titles

- Demonstrate library catalog genre search: “English literature periodicals.” “American literature periodicals.”

- Demonstrate library’s nineteenth-century periodical databases or other periodicals research resources

Case Studies

These case studies are short activities which were developed for use with undergraduate English classes covering the work of Mary Shelley or Elizabeth Gaskell, including an upper-level course on Romantic writers, and a nineteenth-century British literary survey course. They could be used as anecdotes (without spending much time on discussion) integrated into a broader presentation on nineteenth-century literature to describe the practice and effects of serialization and periodicals as publishing venues. They could also be used as a more in-depth activity with students to interrogate the relationship between editor and author and to contextualize texts within their original publication settings in periodicals.

Case Study 1: Mary Shelley’s “The Dream” and The Keepsake

One of the more popular periodical genres in both Great Britain and the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century was the “literary annual.” Issued once a year and marketed as Christmas and New Year’s presents, the typical literary annual was aimed at women readers. Publishers paired writing by popular authors with reproductions of contemporary art into an elegant package, perfect for gift giving. Contents were often selected to match themes associated with femininity, with images and text portraying sentimental or domestic scenes—though gothic tales were also quite popular.

The editors of literary annuals solicited new poems and stories from current authors, and also reprinted work from deceased authors like Byron. Such major writers as William Wordsworth, Sir Walter Scott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Ralph Waldo Emerson all contributed work to literary annuals. Writers could be asked to produce pieces that would be paired with a specific image. One example of how the publishing context of a periodical influenced a text is Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s short story “The Dream,” written for inclusion in a literary annual entitled The Keepsake for 1832. The editor of The Keepsake selected an image by painter Louisa Sharpe, which depicted a young woman seated outdoors, to illustrate Shelley’s story. To accommodate the image, Shelley had to change the setting of a key scene from the heroine’s dimly-lit private rooms to a “well-wooded park” on a sunny afternoon, potentially altering the reader’s understanding of the heroine’s feelings and motivations.[19]

Discussion questions:

- How do illustrations affect your interpretation of a literary text?

- Do the illustrations in the periodical you are examining seem directly tied to the textual contents? If not, why do you think they have been included?

Case Study 2: Elizabeth Gaskell and Household Words

Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford was not originally created as a novel. The text originated in a short story entitled “Our Society at Cranford” which appeared in the 13 December 1851 issue of Charles Dickens’ journal Household Words. Dickens had recruited Gaskell as a contributor based on the strength of her novel Mary Barton (1848), which resonated with Dickens’ interest in using Household Words to advocate for social reform. Dickens devised the title for the story since Gaskell sent him an untitled manuscript. As editor, he further made several changes, including editing out allusions to his own works. For example, at the end of the installment, he substituted the title of the poem “Miss Kilmansegg and her Golden Leg” for a reference to A Christmas Carol. He also added a final two-line paragraph, shown in Figure 3. Dickens’ correspondence indicates that Gaskell expressed concerns about these.[20]

Figure 3 shows detail of the final page (p. 274, column 2) of “Our Society at Cranford” in vol. 4 (1851–1852) of Household Words, showing two of Dickens’ editorial interventions. Image courtesy of Google Books.

Gaskell’s story was well received by readers of Household Words, and Dickens requested more sketches set in the fictional country town of Cranford. Gaskell composed eight further installments, which were published irregularly through May 1853. Dickens opted to place each sketch as the opening piece for the relevant issue, usually followed by journalistic content. The juxtaposition of Gaskell’s engaging tales with content on contemporary urban and social issues has been noted by modern critics such as Andrew Sanders, who notes, “By mid-1852 the Cranford stories were beginning to seem a little like light relief from the generally gloomy tone of the journal.”[21] The Cranford sketches were collected and published in a single volume by publisher Chapman and Hall in June 1853, with encouragement from Dickens.[22] The initial popularity of the Cranford sketches seems not to have carried over very strongly into the new format. Though further editions were published in the 1850s and 1860s, Recchio asserts that sales were not particularly high.[23]

Discussion questions:

- Consider individual issues of Household Words which contain an installment of Cranford. What content surrounds the sketch? What is your response to reading the sketch with its accompanying content?

- Do you see any thematic connections or fractures between the Cranford sketches and the other content in the issue you are examining?

- Compare and contrast the experience of reading Cranford in individual periodical numbers with the experience of reading Cranford in book format. How does your reading experience or interpretation of the text change?

- As an editor, would you prioritize the text of the periodical, the later nineteenth-century editions? How would you treat Dickens’ editorial changes?

Bibliography

Altick, Robert. The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957.

Lewes, G. H. “The Condition of Authors in England, Germany, and France.” Fraser’s Magazine 35, no. 207 (March 1847): 288–89.

Peterson, Linda H. “Writing for Periodicals.” In The Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers, edited by Andrew King, Alexis Easley, and John Morton. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Recchio, Thomas. Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford: A Publishing History. Burlington: Ashgate,

2009.

Reisen, Harriet. Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2009.

Rooney, Paul Raphael. “Readership and Distribution.” In The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, Volume 2: Expansion and Evolution, 1800–1900, edited by David Finkelstein, 127–50. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

Sanders, Andrew. “Serializing Gaskell: From Household Words to The Cornhill.” The Gaskell Society Journal 14 (2000): 45-58.

Shelley, Mary. Collected Tales and Stories with Original Engravings, edited by Charles E. Robinson. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

Stern, Madeleine. Louisa May Alcott. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950.

Williams, Helen S. “Production.” In The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, Volume 2: Expansion and Evolution, 1800–1900, edited by David Finkelstein, 65–83. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

Endnotes

[1] Robert Altick, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957), 170–71.

[2] Helen S. Williams, “Production,” in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, Volume 2: Expansion and Evolution, 1800–1900, ed. David Finkelstein (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 65–83.

[3] Altick, The English Common Reader, chapter 4; Paul Raphael Rooney, “Readership and Distribution,” in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, Volume 2: Expansion and Evolution, 1800–1900, ed. David Finkelstein (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), 131.

[4] Altick, The English Common Reader, 262–64.

[5] Altick details production costs and distribution of print material in nineteenth-century Britain in chapters 12–15 of The English Common Reader.

[6] Rooney, “Readership and Distribution,” 141-146.

[7] Partial digital archives of volumes under both titles can be found at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000544996.

[8] Partial digital archives are available at https://archive.org/details/pub_englishwomans-domestic-magazine.

[9] Linda H. Peterson, “Writing for Periodicals,” in The Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century

British Periodicals and Newspapers, eds. Andrew King, Alexis Easley, and John Morton (New York: Routledge, 2016), 79-80.

[10] Partial digital archives available at HathiTrust and Internet Archive, see https://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/serial?id=cornhill.

[11] Peterson, “Writing,” 83.

[12] Harriet Reisen, Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2009), 124.

[13] Reisen, Louisa May Alcott, 211.

[14] Madeleine Stern, Louisa May Alcott (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950), 239, 353.

[15] Peterson, “Writing for Periodicals,” 80-87 highlights the examples of well-known writers like George Eliot, Harriet Martineau; see also Marysa Demoor, “Editors and the Nineteenth-Century Press, in The Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers, eds. Andrew King, Alexis Easley, and John Morton (New York: Routledge, 2016), 89-101, which discusses Charles Dickens’ editorial work.

[16] G. H. Lewes, “The Condition of Authors in England, Germany, and France,” Fraser’s Magazine 35 (March): 288–89.

[17] Digitized copies of this volume are available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433074792049&seq=22 and https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_07MPqHbsy3EC/page/n17/mode/2up.

[18] A digitized copy of volume 4 is at: https://archive.org/details/householdwords04dicklond and volume 5 is at: https://archive.org/details/householdwords05dicklond.

[19] Mary Shelley, Collected Tales and Stories with Original Engravings, ed. Charles E. Robinson (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), 155, 383.

[20] Thomas Recchio, Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford: A Publishing History (Burlington: Ashgate, 2009),, 47.

[21] Andrew Sanders, “Serializing Gaskell: From Household Words to The Cornhill,” The Gaskell Society Journal 14 (2000): 49.

[22] Recchio, 63.

[23] Recchio, 66.

Media Attributions

- Private: Maggie_Kopp_Figure_1

- Private: Maggie_Kopp_Figure_2

- Private: Maggie_Kopp_Figure_3