Reference

6 Dictionaries for Archives and Primary Sources

Sara K. Kearns

This chapter delves into the dictionary as an essential tool when reading primary and archival sources. Language transforms over time, across geographical regions, and between cultural communities. Words are added or dropped from vocabularies, spellings change, and meanings evolve. The vagaries of handwriting add to the complications of correctly reading and transcribing a word. A researcher needs a quick, efficient source that will permit them to confirm the existence of a word or clarify the author’s meaning. A dictionary, particularly a dictionary that offers word histories, etymologies, and evidence of use, can be that resource. A dictionary can also offer routes to additional research. This chapter focuses on what have been termed “research dictionaries.” Research dictionaries are generally distinguished from other dictionaries by their inclusion of evidence to substantiate the definitions. The evidence is typically drawn from published texts[1] but may include oral or ethnographical evidence. This is not an absolute definition and, as will be discussed, there are dictionaries that can be relevant to research for other reasons, such as when and where they were created.

This chapter introduces the elements of research dictionaries including: the type of content that may be included in a dictionary, how dictionaries are created, and examples of how dictionaries support the research process. Four research dictionaries that are solid starting points for texts associated with North America and the United Kingdom are the foundation for this chapter: the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the English Dialect Dictionary (EDD), Merriam-Webster (M-W), and the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE). These were chosen because there is ample evidence regarding their creation and lexicographical practices to illustrate how dictionaries are created and maintained. Comparing four dictionaries affords an understanding of which features are standard and what might vary from dictionary to dictionary.[2] These are not the only dictionaries researchers can consult, and discussion is included about identifying other dictionaries.[3] Recognizing that purchasing or subscribing to dictionaries may not be affordable for all institutions or researchers, free or alternative access options are discussed in the “How to Access Dictionaries” section.

This chapter uses the terms “lexicographer,” “researcher,” and “text.” The term “text” encompasses any primary or archival source in which language is used. This includes but is not limited to manuscripts, books, lyrics, films, and social media posts. The term “researcher” is inclusive of anyone, of any age or educational level, who is asking questions of a text. The term “lexicographer” is used to describe both the editorial staff of a dictionary and those who create definitions and other content for a dictionary.

ELEMENTS OF A DICTIONARY

This section presents the kinds of information that may be found in a dictionary that are particularly relevant to reading archival and primary source texts. This is not an exhaustive list of every element that may appear in any dictionary. Each element listed does not appear in every dictionary. What each dictionary calls these elements can vary and so some entries include several possible labels. Finally, the order in which these elements appear varies between dictionaries.

About/ Introduction/Preface/Explanatory Notes: content that is analogous to the “research methods” section of other scholarly sources or a user manual. This is easily the most important information to read when consulting a dictionary for research purposes. If you have questions about reading an entry or the reliability of the information provided, look to these sections. The About section can include functional details like pronunciation and abbreviation charts, or an explanation of the order of information presented in each entry. Consult this section to learn about the lexicographical methods and editorial decisions guiding the types of sources lexicographers consulted, which elements beyond definitions are included, and the standards for inclusion or exclusion from the dictionary.

The 1988 Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary starts with forty-two pages of explanatory material including a chart dissecting the parts of an entry, a narrative of how lexicographers create an entry, a guide to pronunciation and symbols, a glossary of abbreviations used in the volume, and editorial changes from prior editions.[4] A good dictionary makes it easy for a researcher to find the information relevant to their question so no one is forced to read an entire About section, unless they are so inclined. One surprisingly useful piece of information found in the About sections, particularly for print dictionaries, is which alphabetization method is used. Some dictionaries alphabetize letter by letter, ignoring spaces and hyphens (money bags before moneyed), others treat spaces and hyphens as characters that are ordered after letters (moneyed before money bags.)[5]

In online and database-style dictionaries, look for this material under About or Help links. In print dictionaries this information is typically located at the beginning of a volume or set.

Main Entry/Headword: the word being defined, usually formatted in bold font or in all caps. The entry may include variations on the word, including different spellings, singular and plural versions, or the word in commonly used phrases or combinations.[6]

Develop the practice of reading an entire entry and looking at the words that appear before and after to ensure you are seeing all possible definitions and word variations. It is fairly easy to scan a page from a print dictionary to look for word variations. Online dictionaries often display a list of the words that alphabetically come before and after the main entry currently being viewed.

Etymology: akin to the resume of a word. This section shows the history of a word, which can include the different forms it has taken in English, how far back in English it can be found (e.g., Middle English, Old English), and whether it has roots in other languages (Latin, German, Haitian Creole).[7]

Geographical/Regional Labels: indicates the geographical areas associated with the word, either because it is commonly used in or originated in a particular community. Geographic labels can be as broad as a continent (Australia) or as small as a city (Chicago, IL). These labels are usually abbreviations, look in the About section to match location to abbreviation. There may also be maps available, which can be helpful if the regional label does not match current boundaries. A word may have multiple geographic labels and the meaning may vary in different regions.

Definition: an explanation of what the word means. As discussed later in “How Dictionaries are Created,” lexicographers do not prescribe what a word means. Instead, using citation files, lexicographers develop definitions that reflect “what the word means as it is actually used rather than what the definer or someone else thinks it ought to mean.”[8] A main entry may have one definition or many.

Dates/Quotations/Citations: associated with recorded (i.e., published) use of the headword. The quotations are provided as evidence of the meaning of the word and illustrate how a word’s meaning has changed over time. The dates serve both as part of the citation for these quotes and as a timeline of recorded use. A word is often in use in conversation and informally before it can be found in a published text.[9] Additionally, some research dictionaries actively seek new evidence of a word used earlier than currently reported. Therefore, the earliest date and quotation is often qualified as the first known use or first recorded use and may be updated based on further research.

HOW RESEARCH DICTIONARIES ARE CREATED

Understanding how a dictionary is created allows researchers to assess the reliability of the dictionary. Knowing how dictionaries are created also provides space for researchers to engage with and question the information and assess its reliability, as they do with other scholarly sources.

This section explores common practices in creating dictionaries, in particular how words are added to a dictionary. Four dictionaries illustrate the practices: the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the English Dialect Dictionary (EDD), Merriam-Webster (M-W), and the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE). More details about these dictionaries are provided in the Appendix of this chapter. Guidelines for removing, or dropping, words from the dictionary will also be described. For other dictionaries, refer to their About content to learn how they were created.

Scope

Each research dictionary has a scope that determines which words or types of words and definitions will be included. A dictionary intended for use by the general public will focus on words in popular or readily accessible texts like newspapers or novels. A medical dictionary will focus on words in articles and texts read by medical professionals. Editors decide if the dictionary will focus on defining a word’s meaning for a specific time period, usually the present (these are known as “synchronic” dictionaries), or if it will include definitions across time to illustrate how a word’s meaning evolved (known as “diachronic” or historical dictionaries).[10]

The editors of DARE are guided by two principles in framing the scope of their dialect dictionary:

1) Any word or phrase whose form or meaning is not used generally throughout the United States but only in part(s) of it, or by a particular social group; 2) Any word or phrase whose form or meaning is distinctively a folk usage, regardless of region. (By “folk usage,” we mean that which is learned from family and friends rather than from books or schooling.)[11]

The editors also established what would not be included, such as technical language or slang.[12]

Corpus

A corpus is the collection of materials that lexicographers read in order to identify words to be defined and to gather evidence about the meaning of those words. The corpus may be a list of specified publications or a more flexible formula that ensures that the breadth of coverage both meets the dictionary’s scope and can be updated as needed. It is common for the corpus to change over time.

When the OED was proposed, the editors focused on filling the lexicographical gaps left by the two standard dictionaries of the time compiled by Johnson[13] and Richardson.[14] They identified texts and authors that Johnson and Richardson did not cite in their dictionaries. That list of texts and authors became the initial corpus; it was quickly expanded to include “less-read authors of the 16th and 17th century,” and “all of the early English literature, from Robert of Gloucester down to the end of the seventeenth century,” and “chief classics of the present century… and the leading writers of the Victorian era.”[15] Eventually, the OED’s scope grew to become a record of the history of the English language. The corpus broadened to ensure that “contemporary English” is captured and added historical texts that reveal archaic words not already in the OED or earlier evidence of use. The corpus now includes: newspapers, magazines, novels, television scripts, social media, letters and diaries in archives, other historical dictionaries, and primary source databases such as Early English Books Online.[16]

DARE was built on “word lists” compiled for the American Dialect Society’s publication, Dialect Notes. Like the OED, the editors amassed and consulted a collection of texts, but their corpus was compiled from evidence of informal English in sources such as The Journal of American Folklore, small-town newspapers, and “records of local speech.”[17] Because the spoken word, particularly pronunciation, is fundamental to the study of dialects, the editors of DARE created a spoken word corpus by administering a questionnaire via in person interviews conducted from 1965–1970 to over 2700 people in over a thousand communities across the United States. The questionnaire prompted participants to answer questions posed in the format, “What would you call…” The participants were also recorded speaking casually and then reading a children’s story, “Arthur the Rat” to build a dataset of pronunciations.[18]

Few dictionaries start from nothing. Some dictionaries start with the contents of another dictionary, ideally through a formal agreement.[19] Today’s M-W is built on a lineage of dictionaries stretching back almost two hundred years to Noah Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language.[20] To introduce a new dictionary into the conversation, The Macquarie Dictionary was published in 1981 as the first dictionary to present “the use of English in Australia, and in which Australian English becomes the basis of comparison with other national varieties of English.”[21] Rather than creating the dictionary from scratch,

[W]e could not prepare a book of this size without having access to another good dictionary for use as a base. We were fortunate in have access to the Encyclopedic World Dictionary, published by Hamlyn in England in 1971. This dictionary was itself based on the well-known American College Dictionary, first published 1969.[22]

The editors removed entries irrelevant to Australian English, added terms from the Australian vocabulary that were identified in newspapers and other Australian publications, and modified definitions, as necessary, to reflect meanings particular to Australia.[23]

Citation Files & Slips

Citation files are the lifeblood of a research dictionary. They are a dictionary’s accumulated evidence of how words are used in the corpus. The method used at M-W in the 1980s is illustrative of the process described by other dictionaries. For context, M-W refers to this as “reading and marking.”

An editor who is reading and marking will, of course, be looking for examples of new words and for unusual applications of familiar words that suggest the possible emergence of a new meaning but will also be concerned to provide evidence of the current status of variant spellings, inflected forms, and the stylings of compound words, to collect examples that may be quotable as illustrations of typical use in the dictionary, and to record many other useful kinds of information. In each instance the reader will underline the word or phrase that is of interest and mark off as much context as is considered helpful in clarifying the meaning. This example of a word used in context is called a citation of the word…

These samples of words in bracketed context are put onto 3 x 5 slips of paper, and the citation slips are placed in alphabetical order in rows of filing cabinets. They will be used, as needed, by the editors in their roles as writers of definitions and certain other parts of dictionary entries. The editors engaged in this ninth edition of the Collegiate reviewed every one of the million and a half citations that had been gathered since the eighth edition was prepared in the early 1970s.[24]

The citations, originally handwritten on pieces of paper and referred to as “slips,” were easily created by any number of people. The EDD solicited slips from members of the public. An article in Pall Mall magazine soliciting volunteers provided formatting guidelines to ensure consistency and legibility.

In the left-hand corner of a half-sheet of note-paper, of the ordinary size, the word is written plainly; in the opposite corner the county in which it occurs, and underneath the meaning with, if possible, an example of its use, taken either from printed sources or the memory of the recorder. To write plainly, it may be added, most men need to print their words.[25]

When dictionaries relied on physical slips, they were organized alphabetically in pigeonholes and file cabinets. Today, citations are added to a spreadsheet or databases to be sorted and stored until needed.[26] An editor assigned a word starts with the file of accumulated citations rather researching the word from scratch. The OED notes that the benefit of a database is that every word in a citation is searchable, expanding the reach of one citation.[27]

The scale of the citation files is astounding, particularly when rendered in the form of paper slips. One of the “big” words for the EDD could have as many as 1,000 slips.[28] A lexicographer visiting the main workspace of the OED, known as The Scriptorium, in 1881 described the space with a particular focus on the slips,[29]

The Scriptorium itself is a modest building enough, consisting of a single long, low room adjoining the editor’s residence; but the walls of this room are literally lined with the bundles of written slips already sent in by readers; these are arranged in alphabetical order by trained helpers, as soon as practicable after their reception, and are then consigned to the pigeon-holes, which cover the whole available wall-space from the floor as high as the hand can reach.[30]

The OED and M-W allocate significant floor and shelf space in their offices to the thousands of slips created in earlier years because the slips are still consulted. M-W houses 15.7 million slips, the OED stores 450–550 boxes of slips.[31]

The accumulation of citations is essential for lexicographers making decisions about whether to add a word to a dictionary. The practice at the OED is to add a word, “if there is sufficient evidence that it is used. Typically, we’d expect to have evidence going back five years, but this is a guideline rather than a hard and fast rule.”[32] Lexicographers apply that flexibility when working with words used in what the OED refers to as “World Englishes,” that is, English-speaking countries outside the UK. This flexibility takes into account circumstances that constrain how much evidence exists, such recognizing that a country with a small population size like Bermuda is unlikely to produce as much content as a more populous country like the Philippines.[33] The lexicographers at M-W also monitor citation files for evidence that a word has been used over time and in a breadth of sources.[34]

Citations are also included as evidence of a word’s meaning in a research dictionary. A researcher consulting the OED may rely on the evidentiary quotations and their publication dates as much as a word’s definition to satisfy a research question; this is explored more in the Research Example 1 section of this chapter. Researchers consulting the EDD and DARE will find similar blocks of quotes and citations. M-W occasionally includes a cited quotation in an entry, but not often. However, the free Merriam-Webster.com site has a feature that automatically compiles examples from the web, offering researchers a snapshot of current use. Finally, DARE, EDD, and OED make some or all of their sources available as either a bibliography or a searchable feature.[35] Researchers can examine the sources to evaluate the scope of the dictionary’s coverage or identify the impact of specific authors or publications on the creation of the dictionary.

Readers, Correspondents, and Crowd-Sourcing

What might be most remarkable about the compilation of research dictionaries is the number of people from the general public who volunteered, and still volunteer, to help. The OED, EDD, and DARE were all initiated by scholarly organizations whose members committed to reading texts and crafting slips. The scope of each project quickly exceeded the capacity of the membership and the editors asked members of the public to be readers or correspondents.

Readers were anyone willing to read assigned texts and mail in slips. The EDD used a variety of readers, from those who created slips based on words found in the books or periodicals they read to volunteers who went through the Dialect Society’s published glossaries of regional dialects, cut out each entry, pasted it to the prerequisite slip of paper, and mailed the slips back to the EDD’s offices.[36] Volunteers could be very enthusiastic. A reader for the OED, Mrs. Moore, was slipping Grew’s Anatomy of Plants when,

she came upon an unusual word describing the seeds of a certain plant; to make the meaning perfectly clear, she took the trouble to procure some of the seeds, gummed them on the slip, and pasted a piece of transparent paper over them.[37]

Today the OED recruits voluntary and paid readers through their Reading Programmes.[38] Volunteers for DARE lent a hand by identifying “possible examples of regionalisms in more than two hundred American novels, short stories, plays, and poems.”[39] DARE also benefited from members of the public who answered the questionnaires and participated in interviews.

Correspondents answered questions because they had a subject expertise or were willing to conduct local research about words. Correspondents included authors contacted by an editor to clarify the use of a word in one of the author’s works. The OED’s editor, James Murray, wrote to the author George Eliot about her use of the word “adust.”[40] Other correspondents, particularly of the EDD, were asked to find evidence of whether a word was known or in use in a community. The staff at the EDD seemed to delight in these communications. Miss J. B. Partridge, a senior assistant, shared the story of how one correspondent answered their request,

We wanted to ascertain the survival of a word once used in the Lancashire mill districts. Our correspondent accordingly, on his way home from business, got into a railway carriage full of mill lasses, and put his question to one of them. She looked round the carriage and said: ‘Eh! any fool ‘ud know that!’ In the Dictionary, the word is described as ‘Still in current use’. We had got what we wanted.[41]

The OED continues to welcome help from the public via the “Contributing to the OED” portion of their website.[42] The OED also used Twitter, now known as “X,” to quickly identify regional differences, such as what item of clothing are referred to as “dungarees,” establish evidence of use for World Englishes, or to identify the earliest known modern meaning in print, such as if the term “mullet” referred to a hairstyle before 1994.[43]

Dropping Words

M-W, as a synchronic dictionary, actively removes, or drops, words from their dictionaries, particularly their print dictionaries.[44] Commercial dictionary companies need to sell copies to stay in business. A key selling point for new editions of commercial dictionaries is currency, that is, including the “newest” words in the dictionary. Currency means new words are added to the dictionary and, in the case of print dictionaries, those words take up space. At a certain point, it is not economically feasible to produce bigger dictionaries, so editors make decisions that maintain the size and costs. One decision is to remove words. Lexicographers at M-W note that, while space is one reason to remove words, they also remove words for lexicographical reasons, and often there is a cross-over between the economic and lexicographical decisions. Words are dropped from a dictionary because:

- The word is obsolete and obscure, as demonstrated by lack of use in publications. An exception is words that are no longer in common use but which appear in classical texts that are still read.

- The word was entered when it was a “new” technology, particularly compound words like “cell phone.” As the technology becomes common, the term becomes self-explanatory. While “cell phone” still appears in M-W, the ubiquity of these phones over landlines could lead to a future when “cell phone” is no longer a separate entry from “phone.”

- The dictionary changed its scope and removed words outside of that scope. For instance, some dictionaries included general facts in addition to definitions, like an encyclopedia. An editor may decide to remove words without definitions such as proper nouns like a person or a place if there is no meaning beyond who or what the person or location is.

- They were “ghost” or fake words that had been entered as a result of a typo, other error, or a joke.[45]

Words can be re-entered in a dictionary with evidence of use.[46]

The fact that words can be dropped from a dictionary illustrates how dictionaries are products of the time when they were created. Mismatches between when the dictionary was created and when the text being studied was created can result in an unproductive search or an incorrect conclusion.

Selecting a Dictionary

Most researchers can rely on whatever dictionary is handy. However, when the use of a term in the text doesn’t match the definition, the word isn’t in the dictionary, or a word’s meaning, etymology, or dates of use is pivotal to the research question, a different dictionary may be required. What follows are suggestions to match a text to a dictionary.

- Creation date(s): Try to match the date a text was created to the date a dictionary was compiled. A historical (diachronic) dictionary is useful because it tracks how a word’s meaning has changed over time. Reading an older text and don’t have access to a historical dictionary? Look for one published around the same time as the text because it has a higher likelihood of including the word and meaning in question.

- Geography: Where was the text created and/or where did the creators live? Try a standard English Dictionary for the country or region where the text originated or its creator lived in order to locate regional definitions or spellings. The Australian The Macquarie Dictionary, is a good example. Consult dialect dictionaries like DARE or the EDD to resolve confusion related to regionalisms.

- Scope: As will be illustrated below in Research Example: Language & Scope, some dictionaries are created to meet a specific need. When reading texts using jargon specific to a profession or activity, search for a dictionary in that field.

- Research need: If the meaning of a word affects your research path

look for a research dictionary that includes citations and other elements so you can track the lexicographers’ research methods.

RESEARCH EXAMPLES

What follows are two examples of how research dictionaries have been used by classes when reading archival material and how different elements of dictionaries can answer research questions.

Example 1: Date Text Was Created & Citations

A first-year university class was transcribing recipes from manuscript cookbooks held in Kansas State University’s Richard L. D. and Marjorie J. Morse Department of Special Collections. Students working with the Hall Family recipe book encountered a recipe for “gravel.” In fact, the Hall Family’s manuscript recipe book, compiled in England between 1750 and 1865, includes at least three recipes for “gravel.” The book’s authors recorded recipes for any concoction that they prepared, whether it was a food, ointment, or paint. Recipes include: chickens buttered, gripes [sic] in horses, ginger beer, green wash for rooms, and tincture for wounds. Due to the breadth of recipes and the challenges of transcribing handwriting, students and the librarian were not sure if the gravel recipe was for house or body, or if they were simply mis-reading the recipe.

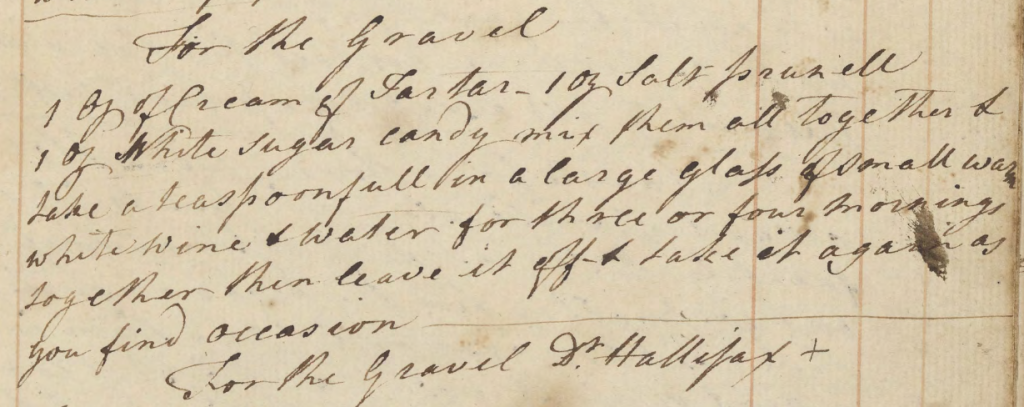

One of the recipes (Image A) reads:

For the Gravel

1 oz of cream of tartar – 1 oz salt-prunelle

1 oz white sugar candy mix them all together & take a teaspoonfull in a large glass of small warm white wine & water for three or four mornings together then leave it off & take it again as you find occasion.[47]

The class first consulted Wikipedia, a common choice when starting research in a field new to the researcher, not the least because the footnotes can lead to additional resources. In this instance, the explanation merely confirmed what the class knew, the term “gravel” as used in the United States today commonly refers to small rocks used for roads and driveways or in concrete.[48] The free Merriam-Webster.com dictionary proffered three definitions for “gravel” as a noun. The first was labeled as obsolete and related to “sand.” The second was the small rock meaning. The third was, “small calculi[49] in the kidneys and urinary bladder.”[50] Merriam-Webster.com offered additional meanings under a Medical Definition heading,

1 : a deposit of small calculous concretions in the kidneys and urinary bladder

compare microlith

2 : the condition that results from the presence of deposits of gravel.[51]

The definition of “gravel” as a medical condition made sense for a recipe drunk three mornings and then as needed (and three recipes in one book suggests it was a condition that at least one person in that family would have gladly stopped suffering).

For a first-year undergraduate student practicing transcribing, the definition in Merriam-Webster.com can be enough of a confirmation that “gravel” is used in a context that involves drinking a concoction. Someone researching the history of recipe books or the history of medicine may need additional evidence. For instance, was “gravel” used in a medical context when the recipe book was created? Can the ingredients in the recipe offer clues? Sugar and wine seem obvious, but what is “salt-prunelle”? A research dictionary that records the history of the English language, including dates and citations confirming when different meanings were ascribed to the word can be an efficient way to confirm an idea and keep working. In this case, the class was curious to learn more and consulted the online OED.

The OED provides seven definitions for “gravel” as a noun, including one related and rocks used on roads. One definition is medical, one is related to brewing:

- Pathology. A term applied to: aggregations of urinary crystals which can be recognized as masses by the naked eye (as distinguished from sand); (also) the disease of which these are characteristic. ‘Also popularly used to indicate pain or difficulty in passing urine with or without any deposit’.

- Brewing. Applied to yeast-cells swimming in beer with the appearance of fine gravel.[52]

Medicine and brewing fall within the range of recipes in this book, which was promising. The OED also provides examples of the word used in a sentence for context for each definition, along with the citation and date for the context sentence. For the medical meaning, one sample sentence is:

“1796 J. Morse Amer. Universal Geogr. (new ed.) II. 351 Those [waters] of St. Amand cure the gravel and obstructions.”

Other evidentiary sentences for the medical definition date between c1400 and 1874. There is only one sentence offered for the brewing definition:

“1882 tr. Thausing’s Beer ii. §2. ii. 596 It is a bad sign if the beer..is not transparent, when it has an appearance as if a veil was drawn over it, when no ‘gravel’ can be perceived.”[53]

While the citations do not provide an absolute answer, the connection between gravel and water for treatment seems to favor the medical definition.

Researching the ingredients also provides insight, particularly the mystery term, “salt-prunelle.” When looking up “salt-prunelle,” both Merriam-Webster.com and the OED refer the researcher to “sal prunella.” Merriam-Webster.com’s definition is brief, “potassium nitrate fused and cast in balls, cakes, or sticks.”[54] The OED’s entry is more expansive. While the definition itself is not enlightening, “Fused nitre cast into cakes or balls,” the other elements provide more evidence. These include alternative spellings, the note that “prunelle” was used in the 1800s, and several evidentiary sentences from the 17- and 1800s that describe using the substance in medicine, including one from the 1747 Primitive Physick by Wesley, “Take..two Tea-spoonfuls of Sal Prunellæ an hour before the fit.”[55]

In summary, the dates of use for a medical meaning correlate to the dates of the recipe book (1750–1865), while the earliest recorded evidence for brewing is seventeen years after the book was compiled. A key ingredient, “salt prunelle,” is defined as being used for medicinal purposes and held this meaning when the recipe book was compiled. This accumulation of evidence permits the researcher to move forward with the medical definition; they can also have potential research routes based on the sample quotations, including dates, other treatments, and sources of medical guidance.

Research Example 2: Language and Scope

This example explores using a dictionary because of when and why it was created. Students in an upper-level university French translation class were translating the manuscript diary of a French infantryman during World War I.[56] While competent in French, the researchers were translating not just the French of a hundred years ago but terms unique to the military and to how that specific war was fought. Additionally, because the soldier was writing for himself, he naturally used slang terms, “l’argot.”

The professor consulted the librarian with a request for sources to help students understand the WWI and military references. The usual French language and English-French bilingual dictionaries were not specific enough. Encyclopedias and histories provided context, but not concise explanations. The library held a few early-twentieth-century French dictionaries, although none with extensive military terms, but had access to the digital repository HathiTrust and its many digitized texts.[57]

The librarian searched HathiTrust for the terms dictionaries French in the Subject field. Limiting the results to those published between 1910 and 1920 returned dictionaries related to World War I. These included bilingual or multilingual dictionaries produced during the war, such as French-English or French-English-German lexicons that provided word lists in the main languages of the conflict. The professor and students found one dictionary particularly helpful, a French-Spanish volume, Dictionnaire des Termes Militaires et de l’argot Poilu.[58] The dictionary is comprised of the language, including slang (l’argot), used by French soldiers (poilu) during WWI. While the definitions are in Spanish, many entries are supplemented with songs and quotes in French, plus there are diagrams of airplanes, photos of weapons, and renderings of badges indicating rank and branch of service. Rather than digging through books or scholarly journals, the researchers in the class could reference the dictionary to quickly understand the meaning of a word. If they needed further information, they had more context to focus their searches.

When working with primary source materials that are historical, there are a surprising number of contemporaneous dictionaries. Even more pertinent, there are many dictionaries devoted to niche, and not so niche, disciplines. It is always worth a search in library catalogs, digital repositories, and WorldCat for these sources.

How to Access Dictionaries

Researchers are encouraged to contact a reference librarian or subject liaison librarian to find relevant dictionaries for their projects. Academic or public libraries are excellent resources for researchers who need to access dictionaries that require subscriptions, are esoteric, or are so extensive that they were published in multiple volumes. In the United States, many libraries at public universities permit members of the public to access their physical collections and subscription databases when in the library. If a local public library does not have the needed dictionary a library in larger community nearby might. Larger public libraries sometimes allow people from outside their immediate community to register for a library card and access their collections, including subscription databases. Depending on where a researcher lives, their state, county, or province may provide access to subscription databases. Finally, dictionaries may be available to borrow from other libraries using Interlibrary Loan. This service is usually offered for print books, particularly rare editions may be difficult to borrow. Additionally, ebooks are currently not easily loaned between libraries. WorldCat is a union, or collective, library catalog where researchers can search for dictionaries and learn whether a library nearby owns a copy. Researchers should ask a librarian about what resources are available to them.

Dictionaries that are no longer under copyright or are in the public domain can be found in digital repositories. These digitized dictionaries are free to use and frequently are keyword searchable, although the results vary depending on the quality of the scans. In addition to the previously discussed HathiTrust, digitized dictionaries can be found in large digital collections like:

Additionally, researchers can find an expansive list of open access or public domain dictionaries, organized by subject and language, at The University of Pennsylvania Library’s Online Books Page.[59]

This list is useful to browse and gain perspective on the breadth of dictionaries available.

Appendix: Dictionaries

This section looks closely at the four main dictionaries discussed in this chapter.

Dictionary: Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE)

Scope: DARE is a diachronic dictionary initiated by the American Dialect Society, which was formed in 1889 to study “the English dialects of America with regard to pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, phraseology, and geographical distribution.”[60] The DARE project is now hosted by the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Dates Covered: Colonial America to the present [61]

Geographic Focus: American English

Corpus/Sources Consulted: Word lists collected and in the society’s publication, Dialect Notes, a DARE questionnaire administered 1965–1970, and a corpus of “oral and written, published and unpublished materials” to identify words and their meanings.[62]

Etymology Provided: “DARE doesn’t try to trace every word back to its ultimate origin, but only to explain how it got into American English.”[63]

Date of First Recorded Use Provided: Yes. Quotation blocks for each word provide a date, an abbreviated citation, and a brief phrase, with citation, illustrating the word in context. The first entry is the first recorded use in the US.[64]

Additional Notes:

- The print edition is a six-volume set.

- When using the print volumes, refer to volumes I (1985) or VI (2013) for the maps and the abbreviations, particularly the abbreviations for regions in the US, indicated in the entries. Alternatively, the maps and lists of regional distribution labels are available online.

- The fifth volume contains the bibliography of sources referenced in the quotation blocks. The bibliography is also available online. The online bibliography also indicates how many entries cite a given source.

Access: DARE is available online by subscription.

DARE is available as a six-volume print set; print editions are available at academic and some public libraries. Search WorldCat for DARE to find editions in a library near you.

Fieldwork Recordings of the 1965–1970 interviews are available through the University of Wisconsin.

Early issues of Dialect Notes are available via HathiTrust.

Dictionary: English Dialect Dictionary (EDD)

Scope: The EDD is a historical dictionary that, according to its title page, covers “complete vocabulary of all dialect words still in use, or known to have been in use during the last two hundred years.”[65] Working under the auspices of the English Dialect Society, formed in 1873, the lexicographers’ mission was to record all English dialects in one dictionary before the dialects disappeared.[66]

Dates Covered: 1700–1903

Geographic Focus: British Isles including England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Additionally, “[i]t also includes American and Colonial dialect words which are still in use in Great Britain and Ireland, or which are to be found in early-printed dialect books and glossaries.”[67]

Corpus/Sources Consulted: The EDD’s foundation is a set of over seventy glossaries compiled by lexicographers, primarily members of the English Dialect Society, to record dialects in specific regions of the UK. Additional sources consulted include magazines, agricultural manuals, novels, reference materials such as plant identification guides, and members of the community who spoke or knew the dialect.[68]

Etymology Provided: The focus of the EDD is on identifying unique words and their meanings in different districts, rather than tracing the words to their historical sources.[69] Each entry indicates the county, or district, where the word or meaning has been identified to have been in use. When print evidence is not available, the “initials of the persons who supplied the information” are listed.[70] A list of these correspondents is provided at the start of volume I and in the backmatter of volume 6.

Date of First Recorded Use Provided: Because the EDD is a dialect dictionary, the emphasis is on the spoken word and the region where it was used.[71] When written evidence of the word and its dialectical meaning is available, an abbreviated citation with a date is offered.

Additional Notes:

- The most concise explanation of how to read an entry is:

In the first place, the article on each word will begin with a sort of geographical summary, from which may be learned the exact region in which it occurs, and, if necessary, those regions in which, contrary to what might be expected, it is not to be found. Then will follow an account of the divers shades of meaning with which the word is used in various localities, and of its varying forms. Examples will be quoted, and in all cases the authority for a meaning will be given.[72]

- Researchers who are unfamiliar with counties and districts in the UK will want a copy of the abbreviations on hand. These abbreviations appear in the front matter of volume I and as part of the back matter of volume VI.

- The lists of bibliographic references and correspondents are available at the online version created under the direction of Dr. Manfred Markus (link below). The list of correspondents is especially helpful as it matches the correspondents’ full names to their initials, which is how they are cited in the entries; the lists provided in the front matter of the printed volumes only identify correspondents by names and do not specify their initials.

Access: The EDD is available as a free, searchable database available under Creative Commons License CC-BY 4.0.

The print volumes are digitized at the Internet Archive:

Dictionary: Merriam-Webster.com (M-W/M-W.com) (free version)

Scope: M-W.com is a synchronic dictionary that focuses on current use; unlike the other three dictionaries, M-W will remove words no longer in use.[73]

Dates Covered: 1755–present. Since the Third International Dictionary, published in 1961, M-W follows the guideline that, “if a word was not still in common use by 1755, we would not enter it.”[74]

Geographic Focus: American English[75]

Corpus/Sources Consulted: M-W focuses on “published edited text” although they are expanding their sources to include social media like Twitter, now known as X.[76] Lexicographers at M-W have access to paper citation files collected from published works since the late 19th century through the 2010s, digital citation files from 1980s to the present, subscriptions to newspapers, magazines, plus a large library of books.[77]

Etymology Provided: For some, but not all words.

Date of First Recorded Use Provided: Sometimes. For some terms, a general time period is given, such as “before 12th century.” For others, a more specific date is given.

The definitions are typically, but not exclusively, listed in historical order, with the oldest first.[78]

Additional Notes:

M-W is a dictionary company that publishes many dictionaries for a variety of purposes. It is not considered to be a research dictionary in the way the other dictionaries in this chapter are. For instance, the entries do not systematically include source citations and dates. It was selected for this chapter because of the availability of details about the practices of the lexicographers and insight into a commercial, current dictionary.

Access: The free site, Merriam-Webster.com, provides access to definitions to over 200,000 words.

Merriam-Webster Unabridged, which expands on Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged, includes definitions for 490,000 terms and is available online for subscription. M-W Unabridged also includes access to the Collegiate Dictionary and the Medical Dictionary.

Many libraries have a copy of Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. Check WorldCat for a copy near you.

Dictionary: Oxford English Dictionary (OED)

Scope: The British Philological Society proposed the OED in 1857 with the intent to address “deficiencies” in the two standard dictionaries of the time by Johnson and Richardson.[79] The OED is a diachronic dictionary, “it not only defines the language of the present day, it also records its use at any period within the Dictionary’s coverage.”[80] Ultimately, the scope of the OED has expanded to record the history English language, to include writing definitions that track the development in meaning, as evidenced by published sources.[81]

Dates Covered: 1150–present [82]

Geographic Focus: English-speaking world[83]

Corpus/Sources Consulted: Given the breadth of the OED’s mission, almost anything printed in English in English-speaking countries is a potential source, from novels and newspapers to academic publications and dictionaries.[84] They also track online sources such as Twitter, now known as X, and a ‘“monitor corpus” of web pages totalling around 16 billion words, which is updated monthly.”[85] The OED welcomes suggestions from the public and used Twitter to poll the public in order to ascertain geographic/cultural variations in meaning.[86]

Etymology Provided: Yes. In the cases when it is unknown, it is indicated by the terms, “origin unknown” or similar.[87]

Date of First Recorded Use Provided: Yes.

Additional Notes:

The online version includes a publication note for each entry, indicating the date it was updated and whether the word appeared in earlier editions.

Access: The OED is available online by subscription.

Many academic and some public libraries subscribe to the OED online.

The second edition in print includes twenty volumes and is available at academic and some public libraries. Search WorldCat to find editions in a library near you.

The first edition of the OED is available for free via the Internet Archive under its original title, The New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (links below). This edition may prove suitable for researchers working with texts that pre-date its publication. Because the OED is continuously updated, it is possible that earlier evidence of a word’s meaning may have been found after the first edition.

Volume I. A and B. (1888)

Volume II. C. (1893)

Volume III. D and E. (1897)

Volume IV. F and G. (1901)

Volume V. H to K. (1901)

Volume VI. [part I] L. (1908)

Volume VI. [part II] M and N. (1908)

Volume VII. O, P. (1909)

Volume VIII. [part I] Q, R. (1914)

Volume VIII. [part II] S-Sh (1914)

Volume IX. Part I. Si-St. (1919)

Volume IX. Part II. Su-Th. (1919)

Volume X. Part I. Ti-U. (1926)

Volume X. Part II. V-Z. (1928)

References

Aubin Rieu-Vernet, J. L’argot Des Poilus, Ou, Le Langage Dans Les Tranchées. Madrid: Vernet, 1918. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008891125.

Bailey, Pippa. “How the English Language Is Made.” New Statesman, June 24-June 30, 2022. ProQuest Central.

Bailey, Richard W. “Research Dictionaries.” American Speech 44, no. 3 (1969): 166–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/454580.

Berg, Donna Lee. A Guide to the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Brewster, Emily, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski. “Corrections, Clarifications, and Grave Transgressions.” Produced by John Voci. Word Matters, May 3, 2022. Podcast, MP3 audio, 16:28. https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-87-corrections-clarifications-grave-transgressions, archived May 11, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230511212353/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-87-corrections-clarifications-grave-transgressions.

———. “How to Read a Dictionary Entry.” Produced by Adam Maid and John Voci. Word Matters, November 17, 2020. Podcast, MP3 audio, 18:04. https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-17-dictionary-entry, archived November 26, 2020, at https://web.archive.org/web/20201126052045/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-17-dictionary-entry.

———. “How Words Are Dropped from the Dictionary.” Produced by Adam Maid and John Voci. Word Matters, October 20, 2021. Podcast, MP3 audio, 16:00. https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-61-words-dropped-from-the-dictionary, archived archived May 14, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230514091837/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-61-words-dropped-from-the-dictionary.

———. “Inside Our Citation Files.” Produced by Adam Maid and John Voci. Word Matters, January 18, 2022. Podcast, MP3 audio, 22:10. https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-72-citation-files, archived June 9, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230609163556/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-72-citation-files.

———. “Skunked Words.” Produced by Emily Brewser and John Voci. Word Matters, June 21, 2022. Podcast, MP3 audio, 20:35. https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-94-skunked-words, archived May 19, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230519221213/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-94-skunked-words.

———. “The Newest Words in the Dictionary.” Produced by Adam Maid and John Voci. Word Matters, January 4, 2022. Podcast, MP3 audio, 28:30. https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-70-newest-words, archived June 9, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230609191421/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-70-newest-words.

———. “When Dictionaries Drop Words.” Produced by John Voci. Word Matters, June 14, 2022. Podcast, MP3 audio, 25:38. https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-93-when-dictionaries-drop-words, archived June 9, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230609162802/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-93-when-dictionaries-drop-words.

Cassidy, Frederic G., Joan Houston Hall, and Luanne Von Schneidemesser, eds. “Acknowledgements.” In Dictionary of American Regional English, Vol. I: Introduction and A–C. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985.

———. Dictionary of American Regional English. Vol. IV: P–SK. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002.

———. “Introduction.” In Dictionary of American Regional English, Vol. I: Introduction and A–C. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985.

Cook, Albert S. “The Philological Society’s English Dictionary.” The American Journal of Philology 2, no. 8 (1881): 550. https://doi.org/10.2307/287130.

“Definition of Calculi.” In Merriam-Webster.com, June 24, 2023. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/calculi, archived December 3, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20221203071328/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/calculi.

“Definition of Gravel.” In Merriam-Webster.com, June 23, 2023. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gravel, archived June 29, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230629152317/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gravel.

“Definition of Sal Prunella.” In Merriam-Webster.com. Accessed July 1, 2023. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sal+prunella, archived January 11, 2024 at https://web.archive.org/web/20240111132725/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sal%20prunella.

Delbridge, Arthur, ed. The Macquarie Dictionary. [1st edition]. St. Leonards, N.S.W: Macquarie Library, 1981.

Dent, Jonathan. “What Do ‘dungarees’ Mean to You? Crowdsourcing an Answer from Twitter.” Oxford English Dictionary (blog), March 29, 2019. https://public.oed.com/blog/what-do-dungarees-mean-to-you-crowdsourcing-an-answer-from-twitter/, archived February 5, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230205224719/https://public.oed.com/blog/what-do-dungarees-mean-to-you-crowdsourcing-an-answer-from-twitter/.

Dictionary of American Regional English. “FAQ: Getting Started.” Accessed June 10, 2023. https://www.daredictionary.com/page/23, archived July 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230706014730/https://www.daredictionary.com/page/23.

———. “Introduction to DARE Volumes in Print.” Accessed June 29, 2023. https://www.daredictionary.com/page/95, archived July 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230706014223/https://www.daredictionary.com/page/95.

———. “What Is DARE?” Accessed July 2, 2023. https://dare.wisc.edu/about/what-is-dare/, archived November 1, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231101174720/https://dare.wisc.edu/about/what-is-dare/.

Eliot, George. “Letter 791205A: George Eliot to James Augustus Henry Murray,” December 5, 1879. Murray Scriptorium. https://www.murrayscriptorium.org/id/Letter791205A, archived August 16, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220816102313/https://www.murrayscriptorium.org/id/Letter791205A.

“Gravel.” In Wikipedia, June 24, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gravel&oldid=1161764647, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110202739/https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gravel&oldid=1161764647.

“Gravel, n.” In OED Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed June 28, 2023.

Hall Family Recipe Book. Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, England, 1750. https://findingaids.lib.k-state.edu/item-30-hall-family-n-a, archived January 12, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240112065949/https://findingaids.lib.k-state.edu/downloads/manuscript-cookbook-collection.pdf.

Jain, Nalini. “Evolution of the English Dictionary, 1600–1960.” India International Centre Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1984): 207–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23001660.

Johnson, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from Their Originals, and Illustrated in Their Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers: To Which Are Prefixed, a History of the Language, and an English Grammar. London: J. F. and C. Rivington [etc.], 1785. http://archive.org/details/dictionaryofengl01johnuoft.

Markus, Manfred. “OED and EDD: Comparison of the Printed and Online Versions.” Lexicographica 37, no. 1 (November 12, 2021): 261–80. https://doi.org/10.1515/lex-2021-0014.

McPherson, Fiona. “Meet the Editors: New Words.” Oxford English Dictionary (blog), July 28, 2021. https://public.oed.com/blog/meet-the-editors-new-words/, archived June 9, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230609180928/https://public.oed.com/blog/meet-the-editors-new-words/.

Merriam-Webster. “Help: Etymology.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/explanatory-notes/dict-etymology, archived July 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230706025606/https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/explanatory-notes/dict-etymology.

———. “How Does a Word Get into a Merriam-Webster Dictionary?” Accessed July 5, 2023. https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/faq-words-into-dictionary, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110172417/https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/faq-words-into-dictionary.

Oxford English Dictionary. “Collecting the Evidence.” Accessed July 5, 2023. https://public.oed.com/history/rewriting-the-oed/collecting-the-evidence/, archived May 4, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230504081915/https://public.oed.com/history/rewriting-the-oed/collecting-the-evidence/.

———. “Contributing to the OED.” Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.oed.com/information/using-the-oed/contributing-to-the-oed/, archived January 4, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240104164140/https://www.oed.com/information/using-the-oed/contributing-to-the-oed/.

———. “Language Research Programme.” Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.oed.com/information/about-the-oed/language-research-programme/, archived January 11, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240111134514/https://www.oed.com/information/about-the-oed/language-research-programme/?tl=true

———. “OED Terminology.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.oed.com/information/understanding-entries/oed-terminology/, archived July 24, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230724152201/https://www.oed.com/information/understanding-entries/oed-terminology/.

———. “Reading Programme : Oxford English Dictionary.” Accessed July 5, 2023. https://www.oed.com/page/reading/Reading$0020Programme, archived October 3, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20221003111827/https://www.oed.com/page/reading/Reading$0020Programme.

Pall Mall Gazette. “The English Dialect Dictionary.” December 6, 1894. British Library Newspapers.

Paskin, Willa. “The Mystery of the Mullet.” Produced by Benjamin Frisch and Willa Paskin. Decoder Ring, August 14, 2020. Podcast. MP3 audio, 50:34. https://slate.com/podcasts/decoder-ring/2020/08/the-history-of-the-mullet, archived December 4, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231204194540/https://slate.com/podcasts/decoder-ring/2020/08/the-history-of-the-mullet.

Pearsall, Judy. “Diachronic and Synchronic English Dictionaries.” In The Cambridge Companion to English Dictionaries, edited by Sarah Ogilvie, 31–44. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Richardson, Charles. A New Dictionary of the English Language. London: W. Pickering, 1836. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011725791.

“Sal-Prunella, n.” In OED Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed June 28, 2023.

Sheldon, E.S. “First Year of the Society.” Dialect Notes. 1 (1890): 1–12. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008324447.

Svensén, Bo. Practical Lexicography: Principles and Methods of Dictionary-Making. Oxford England: Oxford University Press, 1993.

“The Making of the Dictionary.” The Periodical 13, no. 143 (February 1928): 3–32. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000682112.

Trench, R. Chenevix, Furnivall, F. J., and Coleridge, Herbert. “Proposal,” Philological Society July 1857. https://global.oup.com/uk/archives/pdf/Major%20Projects/OED%20Proposal%201857.pdf, archived February 1 2023 at https://web.archive.org/web/20230201084951/https://global.oup.com/uk/archives/pdf/Major%20Projects/OED%20Proposal%201857.pdf

Urdang, Laurence, and Robert Burchfield. “To Plagiarise, Purloin, or Borrow.” Encounter, December 1984. https://www.unz.com/print/Encounter-1984dec-00071/archived April 22, 2021, at https://web.archive.org/web/20210422230459/https://www.unz.com/print/Encounter-1984dec-00071/.

Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield, Mass: Merriam-Webster Inc., 1988.

Wright, Elizabeth Mary. The Life of Joseph Wright. London: Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1932.

Wright, Joseph. The English Dialect Dictionary, Being the Complete Vocabulary of All Dialect Words Still in Use, or Known to Have Been in Use during the Last Two Hundred Years; Vol. Volume I: A–C. New York, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1898. http://archive.org/details/englishdialectdi01wrig.

———. The English Dialect Dictionary, Being the Complete Vocabulary of All Dialect Words Still in Use, or Known to Have Been in Use during the Last Two Hundred Years; Volume II. H–L. New York, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905. http://archive.org/details/englishdialectdi03wrig.

Endnotes

[1] Richard W. Bailey, “Research Dictionaries,” American Speech 44, no. 3 (1969): 166–72, https://doi.org/10.2307/454580.

[2] Appendix B breaks down the unique elements of each dictionary.

[3] The author recognizes that this chapter’s scope is constrained and hopes that other authors will contribute chapters that address dictionary use in additional languages and English-speaking cultures.

[4]Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary (Springfield, Mass: Merriam-Webster Inc, 1988).

[5] The author learned this as the “something before nothing rule” during her first library job shelving books: a letter (something) is ordered before nothing (a space).

[6] Donna Lee Berg, A Guide to the Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 11-27.

[7] “OED Terminology,” Oxford English Dictionary, accessed October 31, 2023, https://www.oed.com/information/understanding-entries/oed-terminology/ archived July 24, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230724152201/https://www.oed.com/information/understanding-entries/oed-terminology/ ; Merriam-Webster, “Help: Etymology,” Merriam-Webster.com, accessed October 31, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/explanatory-notes/dict-etymology, archived July 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230706025606/https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/explanatory-notes/dict-etymology; Berg, A Guide to the Oxford English Dictionary.

[8]Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, 29.

[9] Pippa Bailey, “How the English Language Is Made,” New Statesman, June 24 –June 30, 2022, 32, ProQuest Central; Fiona McPherson, “Meet the Editors: New Words,” Oxford English Dictionary (blog), July 28, 2021, https://public.oed.com/blog/meet-the-editors-new-words/, archived June 9, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230609180928/https://public.oed.com/blog/meet-the-editors-new-words/.

[10] Bo Svensén, Practical Lexicography: Principles and Methods of Dictionary-Making (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1993); Judy Pearsall, “Diachronic and Synchronic English Dictionaries,” in The Cambridge Companion to English Dictionaries, ed. Sarah Ogilvie, Cambridge Companions to Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 31–44; Emily Brewster, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, “How Words Are Dropped from the Dictionary,” October 20, 2021, in Word Matters, produced by Adam Maid and John Voci, podcast, MP3 audio, 16:00, https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-61-words-dropped-from-the-dictionary, archived May 14, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230514091837/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-61-words-dropped-from-the-dictionary.

[11] “FAQ: Getting Started,” Dictionary of American Regional English, accessed June 10, 2023, https://www.daredictionary.com/page/23, archived July 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230706014730/https://www.daredictionary.com/page/23.

[12] “FAQ,” DARE.

[13] Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from Their Originals, and Illustrated in Their Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers: To Which Are Prefixed, a History of the Language, and an English Grammar (London: J. F. And C. Rivington [etc.], 1785), http://archive.org/details/dictionaryofengl01johnuoft.

[14] Charles Richardson, A New Dictionary of the English Language (London: W. Pickering, 1836), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011725791.

[15] R. Chenivix Trench, F. J. Furnivall, and Herbert Coleridge, “Proposal” (Philological Society, July 1857), https://global.oup.com/uk/archives/pdf/Major%20Projects/OED%20Proposal%201857.pdf, archived February 1, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230201084951/https://global.oup.com/uk/archives/pdf/Major%20Projects/OED%20Proposal%201857.pdf.

[16] “Collecting the Evidence,” Oxford English Dictionary, accessed July 5, 2023, https://public.oed.com/history/rewriting-the-oed/collecting-the-evidence/, archived May 4, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230504081915/https://public.oed.com/history/rewriting-the-oed/collecting-the-evidence/.

[17] Frederic G. Cassidy, Joan Houston Hall, and Luanne Von Schneidemesser, eds., “Introduction,” in Dictionary of American Regional English, vol. I: Introduction and A-C (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985), xv.

[18] Cassidy, Hall, and Von Schneidemesser, “Introduction.”

[19] Laurence Urdang and Robert Burchfield, “To Plagiarise, Purloin, or Borrow,” Encounter, December 1984, https://www.unz.com/print/Encounter-1984dec-00071/, archived April 22, 2021 at, https://web.archive.org/web/20210422230459/https://www.unz.com/print/Encounter-1984dec-00071/.

[20] Nalini Jain, “Evolution of the English Dictionary, 1600–1960,” India International Centre Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1984): 207–18, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23001660.

[21] Arthur Delbridge, ed., The Macquarie Dictionary, 1st edition (St. Leonards, N.S.W: Macquarie Library, 1981), 12.

[22] Delbridge, The Macquarie Dictionary, 13.

[23] Delbridge, 13-14.

[24]Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, 28.

[25] “The English Dialect Dictionary,” Pall Mall Gazette, December 6, 1894, British Library Newspapers.

[26] Fiona McPherson, “Meet the Editors”; Emily Brewster, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, “Inside Our Citation Files,” January 18, 2022, in Word Matters, produced by Adam Maid and John Voci, podcast, MP3 audio, 22:10, https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-72-citation-files, archived June 9, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230609163556/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-72-citation-files.

[27] “Language Research Programme,” Oxford English Dictionary, accessed November 2, 2023, https://www.oed.com/information/about-the-oed/language-research-programme/, archived January 11, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240111134514/https://www.oed.com/information/about-the-oed/language-research-programme/?tl=true.

[28] Elizabeth Mary Wright, The Life of Joseph Wright (London: Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1932), 387.

[29] Samples of slips submitted by readers to the OED can be viewed on the OED’s history page about contributors, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20230603113843/https://public.oed.com/history/oed-editions/contributors/ on June 3, 2023. Reading these samples illustrates the necessity of the request from EDD editors for good handwriting.

[30] Albert S. Cook, “The Philological Society’s English Dictionary,” The American Journal of Philology 2, no. 8 (1881): 550, https://doi.org/10.2307/287130.

[31] Pippa Bailey, “How the English Language Is Made,” 28-33; “How Does a Word Get into a Merriam-Webster Dictionary?,” accessed July 5, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/faq-words-into-dictionary, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110172417/https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/faq-words-into-dictionary.

[32] Fiona McPherson, “Meet the Editors.”

[33] Bailey, “How the English Language Is Made.”

[34] “How Does a Word Get into a Merriam-Webster Dictionary?”; Emily Brewster, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, “The Newest Words in the Dictionary,” January 4, 2022, in Word Matters, produced by Adam Maid and John Voci, podcast, MP3 audio, 28:30, https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-70-newest-words, archived June 9, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230609191421/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-70-newest-words.

[35] See Appendix B for more details about finding these bibliographies.

[36] “The English Dialect Dictionary.”

[37] “The Making of the Dictionary,” The Periodical 13, no. 143 (February 1928): 9–10, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000682112.

[38] “Reading Programme,” Oxford English Dictionary, accessed July 5, 2023, https://www.oed.com/page/reading/Reading$0020Programme, archived October 3, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20221003111827/https://www.oed.com/page/reading/Reading$0020Programme.

[39] Frederic G. Cassidy, Joan Houston Hall, and Luanne Von Schneidemesser, eds., “Acknowledgements,” in Dictionary of American Regional English, vol. I: Introduction and A-C (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985), ix.

[40] George Eliot, “Letter 791205A: George Eliot to James Augustus Henry Murray,” December 5, 1879, Murray Scriptorium, https://www.murrayscriptorium.org/id/Letter791205A, archived August 16, 2022, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220816102313/https://www.murrayscriptorium.org/id/Letter791205A.

[41] Wright, The Life of Joseph Wright, 385.

[42] “Contributing to the OED,” Oxford English Dictionary, accessed November 2, 2023, https://www.oed.com/information/using-the-oed/contributing-to-the-oed/, archived January 4, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240104164140/https://www.oed.com/information/using-the-oed/contributing-to-the-oed/.

[43] Jonathan Dent, “What Do ‘dungarees’ Mean to You? Crowdsourcing an Answer from Twitter,” Oxford English Dictionary (blog), March 29, 2019, https://public.oed.com/blog/what-do-dungarees-mean-to-you-crowdsourcing-an-answer-from-twitter/, archived February 5, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230205224719/https://public.oed.com/blog/what-do-dungarees-mean-to-you-crowdsourcing-an-answer-from-twitter/; Willa Paskin, “The Mystery of the Mullet,” August 14, 2020, in Decoder Ring, produced by Benjamin Frisch and Willa Paskin, podcast, MP3 audio, 50:34, https://slate.com/podcasts/decoder-ring/2020/08/the-history-of-the-mullet, archived December 4, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231204194540/https://slate.com/podcasts/decoder-ring/2020/08/the-history-of-the-mullet; Bailey, “How the English Language Is Made.”

[44] Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “How Words Are Dropped from the Dictionary.”

[45] Emily Brewster, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, “Corrections, Clarifications, and Grave Transgressions,” May 3, 2022, in Word Matters, produced by John Voci, podcast, MP3 audio, 16:28, https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-87-corrections-clarifications-grave-transgressions, archived May 11, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230511212353/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-87-corrections-clarifications-grave-transgressions; Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “How Words Are Dropped from the Dictionary”; Emily Brewster, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, “When Dictionaries Drop Words,” June 14, 2022, in Word Matters, podcast, MP3 audio, 25:38, https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-93-when-dictionaries-drop-words, archived June 9, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230609162802/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-93-when-dictionaries-drop-words.

[46] Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “When Dictionaries Drop Words”; Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “How Words Are Dropped from the Dictionary”; Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “Corrections, Clarifications, and Grave Transgressions.”

[47][Hall Family Recipe Book] (Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, England, 1750), 143, https://findingaids.lib.k-state.edu/item-30-hall-family-n-a, archived January 12, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240112065949/https://findingaids.lib.k-state.edu/downloads/manuscript-cookbook-collection.pdf.

[48] “Gravel,” Wikipedia, June 24, 2023, 17:22, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gravel&oldid=1161764647, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110202739/https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gravel&oldid=1161764647.

[49] “Calculi,” for the curious, is defined as, “a concretion usually of mineral salts around organic material found especially in hollow organs or ducts” “Definition of Calculi,” Merriam-Webster.Com, June 24, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/calculi, archived December 3, 2022 at https://web.archive.org/web/20221203071328/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/calculi.

[50] “Definition of Gravel,” Merriam-Webster.Com, June 23, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gravel, archived June 29, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230629152317/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gravel.

[51] “Definition of Gravel.”

[52] “Gravel, n.,” in OED Online (Oxford University Press), accessed June 28, 2023, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/81006.

[53] “Gravel, n.”

[54] “Definition of Sal Prunella,” Merriam-Webster.Com, accessed July 1, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sal+prunella, archived January 11, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240111132725/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sal%20prunella.

[55] “Sal-Prunella, n.,” OED Online (Oxford University Press), accessed June 28, 2023.

[56] This class is discussed in more detail in the chapter in this text, “Translating Archives,” by Kathleen Antonioli.

[57] HathiTrust is a collection of digitized books and periodicals. Any user can access material in the public domain. Some materials in the collection are still under copyright and cannot be viewed. See the HathiTrust Help Center for more information: https://hathitrust.atlassian.net/servicedesk/customer/portals

[58] J. Aubin Rieu-Vernet, L’argot Des Poilus, Ou, Le Langage Dans Les Tranchées (Madrid: Vernet, 1918), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008891125.

[59] Archived at: https://web.archive.org/web/20221209071358/https://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/browse?type=lcsubc&key=Dictionaries

[60] E. S. Sheldon, “First Year of the Society,” Dialect Notes 1 (1890): 1–12, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008324447.

[61] “What Is DARE?,” Dictionary of American Regional English, accessed July 2, 2023, https://dare.wisc.edu/about/what-is-dare/, archived November 1, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231101174720/https://dare.wisc.edu/about/what-is-dare/.

[62] “Introduction to DARE Volumes in Print,” Dictionary of American Regional English, accessed June 29, 2023, https://www.daredictionary.com/page/95, archived July 6, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230706014223/https://www.daredictionary.com/page/95.

[63] Frederic G. Cassidy, Joan Houston Hall, and Luanne Von Schneidemesser, Dictionary of American Regional English, vol. IV: P-SK (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002), xi.

[64] Cassidy, Hall, and Von Schneidemesser, IV: P-SK:xi.

[65] Joseph Wright, The English Dialect Dictionary, Being the Complete Vocabulary of All Dialect Words Still in Use, or Known to Have Been in Use during the Last Two Hundred Years; Volume II. H-L (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), http://archive.org/details/englishdialectdi03wrig.

[66] “The English Dialect Dictionary.”

[67] Joseph Wright, The English Dialect Dictionary, Being the Complete Vocabulary of All Dialect Words Still in Use, or Known to Have Been in Use during the Last Two Hundred Years;vol. Volume I: A-C (New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1898), v, http://archive.org/details/englishdialectdi01wrig.

[68] “The English Dialect Dictionary”; Wright, The Life of Joseph Wright.

[69] Manfred Markus, “OED and EDD: Comparison of the Printed and Online Versions,” Lexicographica 37, no. 1 (November 12, 2021): 261–80, https://doi.org/10.1515/lex-2021-0014.

[70] Wright, The English Dialect Dictionary, Volume I: A-C:vi.

[71] Markus, “OED and EDD.”

[72] “The English Dialect Dictionary.”

[73] Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “How Words Are Dropped from the Dictionary.”

[74] Emily Brewster, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, “How to Read a Dictionary Entry,” November 17, 2020, in Word Matters, produced by Adam Maid and John Voci, podcast, MP3 audio, 18:04, https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-17-dictionary-entry, archived November 26, 2020, at https://web.archive.org/web/20201126052045/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-17-dictionary-entry.

[75] Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “How Words Are Dropped from the Dictionary.”

[76] Brewster Emily, Ammon Shea, and Peter Sokolowski, “Skunked Words,” June 21, 2022, in Word Matters, produced by Emily Brewster and John Voci, podcast, MP3 audio, 20:35, https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-94-skunked-words, archived May 19, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230519221213/https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-94-skunked-words.

[77] Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “Inside Our Citation Files.”

[78] Brewster, Shea, and Sokolowski, “How to Read a Dictionary Entry.”

[79] Samuel Johnson, 1785, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from Their Originals, and Illustrated in Their Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers: To Which Are Prefixed, a History of the Language, and an English Grammar, London: J. F. And C. Rivington [etc.], http://archive.org/details/dictionaryofengl01johnuoft; Charles Richardson, 1836, A New Dictionary of the English Language, London: W. Pickering, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011725791; Philological Society, “Proposal.”

[80] Berg, A Guide to the Oxford English Dictionary, 3.

[81] Markus, “OED and EDD”; “The Making of the Dictionary.”

[82] Berg, A Guide to the Oxford English Dictionary.

[83] Berg.

[84] “Collecting the Evidence.”

[85] Bailey, “How the English Language Is Made,” 32.

[86] Fiona McPherson, “Meet the Editors”; Jonathan Dent, “What Do ‘dungarees’ Mean to You?”

[87] Berg, A Guide to the Oxford English Dictionary, 22.