Pedagogy

21 Connecting Primary and Secondary Sources with Annotation and Historical Narrative Introduction

Blake Spitz

Introduction

Advanced lessons concerning primary and secondary sources should not only help students label sources correctly, but also push them to actively participate in the processes of analysis and meaning-making that occur iteratively during both research and secondary content creation. This chapter will outline teaching activities that help students engage with historical narratives and storytelling via the “annotation” of secondary sources with primary sources.

Students often have more experience working with secondary sources in an academic context, encountering information in sources such as textbooks and academic articles, or in popular sources, such as websites like Wikipedia. Scaffolding primary source analysis onto activities that begin with secondary sources can be an effective way to help students see the connections between and unique features of these various source types. As described in this chapter, “annotating” with primary sources involves using the information, emotion, and various meanings gleaned from primary sources to further flesh out and expand information, perspective, and context in narratives first presented in secondary sources.

Annotating historical narratives with primary sources is also useful for instructors concerned about generative artificial intelligence, like ChatGPT. Asking students to work with unique, non-published materials and write or create from that primary source content can potentially prevent some pitfalls of relying only on well-known secondary sources. Generative artificial intelligence may actually be a useful source for initial narratives that students then annotate with their primary sources.

Activity Details

These annotation activities work well for in-person classrooms and are also adaptable for synchronous and asynchronous virtual instruction. All involve presenting students with a secondary source historical narrative or biography, and then using selected primary sources to expand upon and/or question that narrative. The basic activity begins with a short biography or description of an event or group, ideally found through a source accessible and known to students. These sources can be analyzed as secondary sources, and discussed as the types of documents and information students might typically use during research. They should be selected with the age, abilities, and accessibility needs of the class in mind.

As an example, such an activity might begin with a short biography of Albert Einstein, available in the students’ textbooks, or excerpts from Wikipedia[1] or the Nobel Prize Foundation.[2] This source should be read and discussed as a secondary source, and students would then be told that they were going to use primary sources to learn more about Einstein and add to, or annotate, the secondary source. I suggest sources related to Einstein’s interest in and advocacy of civil rights, particularly for Black people in the United States. Possible sources include:

- Einstein’s statement of endorsement for the NAACP journal, The Crisis[3]

- Einstein’s support[4] of Black writer and activist, W. E. B. Du Bois[5]

- Photographs of Einstein’s visit to and lecture at HBCU Lincoln University[6]

- Einstein’s 1946 essay in Pageant magazine, “A Message to my Adopted Country”[7]

- I recommend using an excerpt of the first part of the essay, ending “only by speaking out.” (See Appendix A: “einstein_pageant_1946”)

This activity can be conducted by students alone, in small groups, or even as a whole class. Age-appropriate handouts can be used, if desired, to prompt primary source analysis and to help annotate. Students, again in groups or as a whole class, would then work to annotate the secondary source with information, or open questions, from their primary source analysis. In this example they may add new information to the Einstein biography regarding his concerns with civil rights, his engagement with the Black community, or even perhaps tie these concerns to Einstein’s experiences as a Jewish person fleeing Nazi Germany.

Students should be prompted to focus especially on new details, perspectives, and contextual information presented in the primary sources, and asked to weave that new information and context into the larger narrative of Einstein’s life, either in writing, orally, or some combination of the two. Telling the newer, fuller narrative as a class with students making suggestions and the instructor narrating might be more appropriate for secondary school students, whereas independent or small group work to create new narratives might better fit undergraduate abilities. Students may ask, or be asked, how this new annotated historical narrative about Einstein informs their understanding of his history, of the role of scientists and public intellectuals, or of the act of researching historical figures and writing about them.

Activity Alternatives

Other well-known historical actors or events make excellent topics for annotation with primary sources, either from a local collection or via digitized archival collections from other institutions. Local stories are also a great fit for this activity if schools have collections related to local people or school history. Students enjoy this narrative-building process, gaining access to new ways of seeing a topic or person from the “source” itself, and this can be especially true when getting to rewrite the story of someone they know from popular culture or history, or when given the opportunity to retell a local myth or story.

In the example above, advanced students or classes might question on their own why Einstein’s civil rights activism is less well known, or why it is not a part of his main biography as presented in many secondary sources. The activity itself can also be structured to note this, and prompt discussions about searching thoroughly for sources during research, and especially what it means to annotate with primary sources that highlight intersections with historically marginalized peoples or present their experiences. Doing the latter can be discussed as annotation with a critical purpose, to use primary sources to expand the type and content of historical narratives we tell.

If this emphasis on the critical information literacy components of annotating with primary source activities is of interest as a main learning outcome, activities can be planned around a controversial or complex topic, and with primary sources that provide different or even contradictory perspectives. If student groups, for example, are all given sources that provide quite different annotations to a narrative originally encountered through a shared secondary source, they can begin to see firsthand the subjective nature of primary sources and the necessary attention to issues of bias and intended audience during analysis. Such an activity can expose the power inherent in deciding which sources to search for, reference, and then use during research and content creation, both in students’ own work and in the secondary sources they encounter.

Detailed Example: Du Bois vs Stoddard Debates

In closing, I offer a full “annotating with primary sources” activity that I use often when teaching with the papers of W. E. B. Du Bois.[8] This activity is appropriate for college students or other classes where discussions of racism and historical language can occur. I have used this activity in-person and both synchronously and asynchronously in virtual classes.

In 2019, The New Yorker published an article about two debates between Du Bois and a white supremacist named Lathrop Stoddard.[9] I present students with a heavily excerpted version of the article, stripped down to mostly factual details about these events, one debate in September 1927 on the radio, and one in March 1929, live on stage in Chicago, both sponsored by the Chicago Forum Council (See Appendix B2: “dubois-stoddard_debate_newyorker_excerpt”). The activity prompts students to pretend they are the writer of the full article, and to imagine being a journalist using primary sources from the Du Bois Papers to tell this historical story.

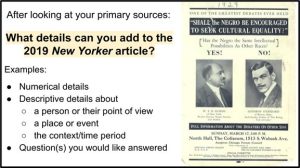

We discuss how the excerpt will be our scaffolding, or skeleton, for building a fuller, more substantial version of this story based on their primary source analysis. The slide below emphasizes the ask of the activity, for them to provide additional details for the narrative story of the debates. I model this work with an example letter from Du Bois to his wife, Nina, where we learn about Du Bois’s busy travel schedule, the number of attendees and large interest in the 1929 debate, and that Du Bois thought it was a success.[10]

Logistically, this activity involves sharing one to two primary sources with five groups of students, and then allowing them time to first read and then discuss their sources and analysis. Sources include correspondence seeking advice from Du Bois about Stoddard four years before the 1927 debate, correspondence between Du Bois and the Chicago Forum Council in 1927 and 1928, an advertisement for the live debate, and correspondence received by Du Bois after the final debate in 1929. The activity then continues as each group, in chronological order of sources, shares out loud with the rest of the class the details they can add to the story of the debates that the class is annotating, and building, together.

In pretending to be journalists doing primary source research for their story, students see how much just a small number of archival sources add to this narrative, especially as the sources offer greater detail into the ideas of Du Bois in relation to Stoddard, and his motivations and work as a public intellectual and activist. Students additionally witness in class the importance of source selection, and therefore of research, to telling a historical story, and also experience the sometimes frustrating lesson that primary sources cannot fully recreate the past, often leaving us with questions or things unknown. However, using their analytical skills and historical imaginations they see in this lesson that primary sources make possible rich narratives about the past, full of details, contrasting truths, and resonant personal reflections and emotions.

For expanded details about this activity and all sources used, see Appendix C.

(See Appendix C: “dubois-stoddard_debate_activity.”)

Conclusion

Primary sources are material or digital evidence of the lived experiences of whole complex human beings, in all their situated contexts. This fact is powerful in instructional settings, where a connection to the past is emphasized via contact with an item from that time period. This is often in contrast to students’ more frequent exposure to and work with secondary sources. Combining these sources with the pedagogical work of annotating secondary source narratives with primary source analysis not only helps students differentiate between these source types, but also has them become familiar, via their own work and practice, with the uses (and limitations) of primary sources in researching and telling full, expansive narratives about past places, events, and people.

Bibliography

1946 Photos of Albert Einstein at Lincoln University. Langston Hughes Memorial Library Special Collections, Lincoln University, PA. https://hbcudigitallibrary.auctr.edu/digital/collection/lupa/id/2211, archived September 24, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230924172512/https://hbcudigitallibrary.auctr.edu/digital/collection/lupa/id/2211/.

“Albert Einstein.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Last modified October 23, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Einstein, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110081614/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Einstein.

“Albert Einstein – Biographical.” NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach. Accessed October 30, 2023. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1921/einstein/biographical/, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110142655/https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1921/einstein/biographical/.

Einstein, Albert. “A Message to my Adopted Country.” Pageant 1, no. 12 (1946): 36–37.

Frazier, Ian. “When W. E. B. Du Bois Made a Laughingstock of a White Supremacist.” New Yorker 95, no. 24 (August 2019).

- E. B. Du Bois Papers. Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/collection/mums312, archived November 27, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231127020634/https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/collection/mums312.

Appendices and Documents

Appendix A: Einstein’s 1946 Pageant essay “A Message to my Adopted Country”

Appendix C: Full class group activity with example primary sources, annotations, and instructor commentary

Document 1 – Visual presentation slide used in class

Endnotes

[1] “Albert Einstein,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified October 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Einstein, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110081614/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Einstein.

[2] “Albert Einstein – Biographical,” NobelPrize.org, Nobel Prize Outreach, accessed October 30, 2023, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1921/einstein/biographical/, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110142655/https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1921/einstein/biographical/.

[3] Albert Einstein, “Statement in congratulation of the Crisis,” ca. October 1931, Box 188, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b188-i447, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110202001/https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b188-i447.

[4] W. E. B. Du Bois Testimonial Dinner Committee, “W. E. B. Du Bois Testimonial Dinner Committee press release,” February 3, 1951, Box 132, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b132-i052, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110201854/https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b132-i052.

[5] W. E. B. Du Bois, “Letter from W. E. B. Du Bois to Albert Einstein,” November 29, 1951, Box 132, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b132-i087, archived April 5, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230405013616/https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b132-i087.

[6] Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, “1946 Photos of Albert Einstein at Lincoln University,” May 3, 1946, Lincoln University Records, Langston Hughes Memorial Library Special Collections, Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, https://hbcudigitallibrary.auctr.edu/digital/collection/lupa/id/2211, archived September 24, 2023 at https://web.archive.org/web/20230924172512/https://hbcudigitallibrary.auctr.edu/digital/collection/lupa/id/2211/.

[7] Albert Einstein, “A Message to my Adopted Country,” Pageant 1, no. 12 (1946): 36–37.

[8] W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/collection/mums312, archived November 27, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231127020634/https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/collection/mums312.

[9] Ian Frazier, “When W. E. B. Du Bois Made a Laughingstock of a White Supremacist,” New Yorker 95, no. 24 (August 2019), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/08/26/when-w-e-b-du-bois-made-a-laughingstock-of-a-white-supremacist, archived June 7, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230607204426/https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/08/26/when-w-e-b-du-bois-made-a-laughingstock-of-a-white-supremacist. See also Appendix B1: “dubois-stoddard_debate_newyorker_full.”

[10] W. E. B. Du Bois, “Letter from W. E. B. Du Bois to Nina Du Bois,” March 26, 1929, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b048-i164, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110201918/https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b048-i164.

Media Attributions

- dubois-stoddard_debate_slide