Reference

5 Exploring Historic Photographs in an Academic Setting: A Framework

Elizabeth Rivera and Sylvia Hernandez

Learning to interpret visual forms of communication is essential in historical research. However, interpreting historical photographs poses various challenges. Because photography is a specific form of communication, it is essential to examine its most basic forms; investigate its meaning, interpret its nuance, and analyze its details. Without descriptive words and directive theses, how do you determine the photograph’s meaning and purpose? This article provides a prescriptive framework to learn the iterative and cyclical process of observing, identifying, interpreting, and analyzing a historic photograph. Simply put, this article teaches how to understand photographs. You will be able to transition from simply seeing a photo to practicing critical analysis and interpretation of photographs.

Photographs have a complex relationship with the written word. In the beginning, a childlike approach is sometimes helpful: forget what you think your audience wants you to see and instead examine the photograph for what it shows. See the entire photograph and engage directly with it. When you learn to understand photographs, you start with the basics and examine what you see, learning to deconstruct the photograph for its content, meaning, and nuance, and applying critical analysis and interpretation.

After completing an initial overview of the photograph, break the photograph into four quadrants. Perhaps even pull out a magnifying glass and see what you may have overlooked. Then describe what you see within each quadrant. Slow down, observe, and describe what is visible within the photograph. You can do this out loud and even with a partner. Take the time to write down your observations. Identify objects and terms that you know, and then describe materials that may be unfamiliar to you. The simplicity of the initial observation makes it tempting to rush through or even skip it, but the practice of breaking the photograph into quadrants and describing what you see allows the mind’s eye to engage in the practice of seeing with the physical eye.

Use the links provided to view images as you work through the framework.

General Tire and Rubber Co., 1951[2]

Protestant Life in Poland, Evangelical bookshop in Cieszyn[3]

Baylor Bear Mascot Placed in Protective Custody, 1946[4]

Or discover more historical photos within the Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections[5]

or in The Texas Collection’s Flickr site[6].

Implementing the Framework

- Observe: A cursory glance at a photo will introduce you to the photo’s purpose. Mentally break the image into sections, or four quadrants. As you make your way through each portion, take note of what you see. Sky, buildings, cars, people, landscapes, are all easy to pick out on an initial pass. See the “big picture.” Specifically, observe the principal subject of the photograph.

- Identify: Determine all potentially useful information embedded within the photograph. Look at the front and back to identify useful clues. When there is writing on the back, it can offer concrete facts about the photo. Unfortunately, the back is often left blank, omitting any written description. Regardless, the front of the photograph provides the context for the larger part of the story. As you observe, make note of any identifying information on the front or back. Dates, names, locations, and events can sometimes be present helping to further the investigation. The photo could have clues as well, signs, banners, photographers’ marks, even the look of the clothes and cars can help. Dating these items is much easier than you think. Consider the types of shows currently on television or that you have seen before. Shows such as Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Downton Abbey, and 1883 are all good reference points to begin narrowing down dates. Use what you are already familiar with to look at something new, especially as you begin building your interpretation.

- Describe: As you continue to look, notice whether the components are static or in motion. Is the photo in black and white, or is it color? As you look more closely at the photograph ask yourself basic descriptive questions, specifically, the “W” questions. Who? What? Where? When? Why? What is happening in the image? Is this a recent picture? If not, when do you think it was taken? Do you see anything specific that seems more important than other things? Keep these ideas in mind as you begin to ask further questions.

- Who is in the photograph?

- What is visible in the photograph? What is happening? What are they doing?

- Where was the photograph taken? Where are they?

- When did this take place?

- Why are they together? The antecedent of they can refer to the people or the materials in the photograph.

As you ask these questions, you will begin to create a story that may or may not be true. Further research will support and confirm that story or expose an alternative.

- Analyze: Dig a little deeper. Determine what is known; examine what can be known and decide what can be deduced or inferred from the photograph. Place the photograph in its most appropriate context of time and place. Why do you think the photograph was taken? Who do you think was the originally intended audience? What era, event, or theme does the photograph illustrate? What style of photography is depicted? Is it journalistic, amateur, or artistic?

Photographs document an assortment of occasions and are taken for various reasons, including portraits, general snapshots, street photography, architecture, publicity, and more. What does the subject seem to say in the photograph? The photograph is a representation of the real world that was available to the eye of the camera at a specific point in time. For example, portrait photography indicates how individuals want to be seen. Consider social media and other online platforms that allow people to share curated albums of themselves including “Photoshopped” and polished or airbrushed photographs. As you determine the purpose of the photo, it will reveal the unfolding story.

- Interpret: Look beyond the immediate subject matter of the photograph and examine the background. What does the minor subject matter tell you? In addition to what you see, also consider what you do not see. Analyze what is included, and what is omitted. For example, photos have reference points we often overlook. Consider who might be doing physical labor versus those who are observing, driving, and even carrying materials. The clothes individuals wear can also be indicative of status, such as laborer, manager, or owner. Social hierarchy is on display.

- Analyze Further: What do you think the purpose and motive of the photographer is? How is this the same as or different from your observations? These two questions are foundational to put the photograph in its proper context regarding time and place. How does this photo fit into what you already know? How does it fit into the collection it came from? How does it fit into a greater story?

As you work through the framework, you will answer these questions and potentially discover more specific questions related to the research. Be open to your interpretation of the historical photograph, knowing that your assertions are informed by your experiences and your ability to “read-between-the-lines” of the photograph. The framework provides a fluid structure so that you can move back and forth among the iterative steps for better analysis (see the chart below.) Interpreting historical images is a process in which you learn to identify factual details within the photograph.

While historic photographs are the immediate focus of this framework, it should be noted that it can be adapted to encourage the interpretation of other primary source documents as well. The Library of Congress[7] and National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)[8] have produced similar frameworks for primary source interpretation. Baylor University archive has a wealth of primary source material available online that other schools can also access for this and other similar exercises.

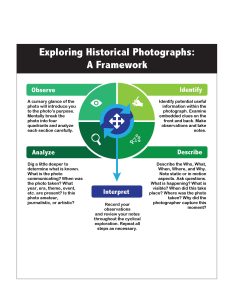

Iterative Steps of Historic Photograph Analysis: A Visual Guide

Use this infographic as an accessible guide to remind you of the iterative steps involved in historic photograph analysis within a structured framework.

Exploring Historical Photographs: A Framework

endnotes

[1] Fred Gildersleeve, Galveston Hurricane, Aug, 16-17, 1915 (2)–Seventeenth and Sea Wall, 1915, photograph, General photo files of The Texas Collection: General–Galveston, Texas, The Texas Collection, Baylor University, https://www.flickr.com/photos/texascollectionbaylor/20272243996/in/album-72157656838463821/, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110213818/https://www.flickr.com/photos/texascollectionbaylor/20272243996/in/album-72157656838463821/ and https://web.archive.org/web/20240110213818im_/https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/20272243996_c289e7393a.jpg.

[2] Fred Marlar, General Tire and Rubber, Co., Waco, TX, 1951, 1951, photograph, General photo files of The Texas Collection: Waco–Businesses–Tire And Rubber Companies–General Tire And Rubber Company, The Texas Collection, Baylor University, https://www.flickr.com/photos/texascollectionbaylor/24817584985/in/album-72157664118569372/, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110213911/https://www.flickr.com/photos/texascollectionbaylor/24817584985/in/album-72157664118569372/ and https://web.archive.org/web/20240110213911im_/https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/24817584985_951874cc6c.jpg.

[3] Hans-Joachim Nollse, Evangelical Bookshop in Cieszyn: Photographs of Protestant Life in Poland, 1983, photograph, Baylor University – Keston Center – Keston Digital Archive, https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/photographs-of-protestant-life-in-poland/1134340?item=1134341, archived July 3, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240703190600/https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/photographs-of-protestant-life-in-poland/1134340?item=1134341.

[4] Jimmie Wilis, Baylor Bear Mascot Chita Goes to Jail: 1946, 1946, photograph, Jimmie Willis Photographic collection, Baylor University-The Texas Collection, https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/baylor-bear-mascot-chita-goes-to-jail-1946/206189, archived July 11, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240711173239/https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/baylor-bear-mascot-chita-goes-to-jail-1946/206189.

[5] “Baylor University Libraries – Digital Collections,” accessed July 11, 2024, https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110151445/https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/.

[6] “The Texas Collection, Baylor University’s Albums,” Flickr, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.flickr.com/photos/texascollectionbaylor/albums/, archived January 10, 2024, at https://web.archive.org/web/20240110214153/https://www.flickr.com/photos/texascollectionbaylor/albums.

[7] “Primary Source Analysis Tool,” Getting Started with Primary Sources, Library of Congress, accessed December 5, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/programs/teachers/getting-started-with-primary-sources/guides/, archived November 11, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231111162144/https://www.loc.gov/programs/teachers/getting-started-with-primary-sources/guides/.

[8] “Analyze a Photograph,” Educator Resources, National Archives and Records Administration, accessed December 5, 2023, https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/worksheets/analyze-a-photograph-intermediate, archived December 17, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20231217232352/https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/worksheets/analyze-a-photograph-intermediate.

Media Attributions

- Private: Rivera Hernandez Historic Photograph Framework