Lesson Plans

15 Analyzing Houston Hip Hop: A Lesson Plan

Julie Grob

As librarians Dave Ellenwood and Alyssa Berger write, “Hip hop is an important frame of reference for many college students because it is such a popular music genre, and for some it is one of their most important sites of identity development.”[1] Students who are introduced to hip-hop-related materials in the primary source classroom often demonstrate high levels of curiosity and engagement and may be able to draw on personal knowledge of hip hop music and culture to better interpret what they are seeing.

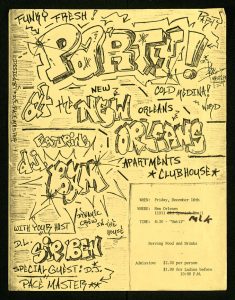

This lesson plan introduces students to the Houston Hip Hop Research Collection at the University of Houston Libraries and teaches them to analyze one of its objects, a party flyer from the Carlos “DJ Styles” Garza Papers. Through this activity, students will synthesize their observations of the primary source with prior knowledge[2] of hip hop music and culture which they may have gained through lived experiences. They will also learn about concepts such as the mediation of collections and the existence of archival silences.[3]

Now a global phenomenon, hip hop first emerged among marginalized Black and Puerto Rican youth in the Bronx in the 1970s. Hip hop is said to be made up of four elements: MC-ing (rapping), DJ-ing, graffiti writing, and b-boying (break dancing).[4] According to author Maco L. Faniel, the popularity of the song “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979 and other developments in the early 1980s helped to spread hip hop culture beyond New York City to other parts of the country, including those that were considered by some to be less sophisticated: “Young people across the country wanted to be hip-hoppers, including the country kids in Houston, Texas.”[5]

Over time, Houston became a significant site for hip hop, producing trailblazers like Geto Boys and DJ Screw and contemporary artists such as Megan thee Stallion and Tobe Nwigwe. During the eighties and nineties, with major record labels focusing on artists from the East Coast and the West Coast, Houston developed a distinctive independent scene. Key contributions to this scene were the Black-owned independent label Rap-A-Lot and its many artists, and the spread of DJ Screw’s chopped and screwed mixtapes.

One longtime member of the city’s music scene is producer Carlos Garza. Originally from Mexico, Garza grew up in Houston, where he became interested in hip hop through watching movies such as Breakin’ (1984) and Krush Groove (1985). Inspired, he started the B-boy group Dynamic Crew with some friends.[6] At the time, he called himself Pace Master.[7] From there, he transitioned to DJ-ing, eventually going by the name DJ Styles.[8] In 1994, he served as one of the producers on the acclaimed Houston album Fadanuf Fa Erybody!! by Odd Squad.[9] Garza continues to produce to this day.

In recent years, a number of institutions have begun documenting hip hop through collecting archival materials.[10] The Houston Hip Hop Research Collection was founded in 2010 to document the unique music and culture of Houston, and reflects both the university’s diverse student body and the area in which it is located. As of this writing, it contains ten archival collections related to local rappers, DJs, and businesses as well as the DJ Screw Sound Recordings collection, which is comprised of over 1600 vinyl records. In addition to institutional collecting, the hip hop community archives its own history, and many materials remain under the care of artists, family members, and private collectors, or community-based archives and museums.[11]

Materials in the Houston Hip Hop Research Collection include audio and video recordings, photographs, rhyme books (lyric books), T-shirts, memorabilia, and ephemera such as concert flyers. Hip hop flyers were originally produced on paper and photocopied in order to both advertise upcoming concerts and “convey the ethos of the show.”[12] Like the flyer associated with this assignment, many of them borrowed their visual style from graffiti.[13] This particular flyer is from Garza’s early b-boying and DJ-ing days, which may make it particularly appealing to college students in their teens and twenties.

This type of material lends itself to the “problem-posing” approach to education articulated by Paulo Freire in which both students and the instructor are in dialogue with each other and learning from one another, and students draw upon their previous knowledge when thinking critically about an object.[14]

As part of the instruction session detailed in the lesson plan below, instructors may wish to play or share examples of some of the predominantly New York City-based hip hop tracks that Garza played as a DJ around the time that the flyer was created.[15] A playlist developed by Garza in 2023 to accompany this lesson plan is attached as Appendix 1. Please note that some of the songs on the playlist contain strong language, sexual imagery, and/or violent imagery. Depending on the audience, instructors may wish to consult the lyrics to unfamiliar songs on lyric websites before introducing them into the classroom.

- Lesson Plan

- Title: Analyzing Houston Hip Hop

- Introduction

- This lesson plan introduces students to the Houston Hip Hop Research Collection at the University of Houston Libraries and teaches them to analyze one of its objects, incorporating their own personal experiences or observations. It could be incorporated into courses in African American Studies, English, or Music, or into high school classes. The lesson plan could be modified for use with another type of primary source object.

- Time Needed: This lesson plan would work in an 80–90 minute class, or could be compressed to work with a 50–60 minute class.

- Objectives

- At the end of the class session, students will be able to analyze an unfamiliar primary source object from the Houston Hip Hop Research Collection.

- At the end of the class session, students will be able to bring their own personal experiences or observations to the analysis of a primary source object.

- PSL Guidelines Learning Objectives Addressed

2A. Identify the possible locations of primary sources.

2D. Understand that historical records may never have existed, may not have survived, or may not be collected and/or publicly accessible. Existing records may have been shaped by the selectivity and mediation of individuals such as collectors, archivists, librarians, donors, and/or publishers, potentially limiting the sources available for research.

3A. Examine a primary source, which may require the ability to read a particular script, font, or language, to understand or operate a particular technology, or to comprehend vocabulary, syntax, and communication norms of the time period and location where the source was created.

3B. Identify and communicate information found in primary sources, including summarizing the content of the source and identifying and reporting key components such as how it was created, by whom, when, and what it is.

4C. Situate a primary source in context by applying knowledge about the time and culture in which it was created; the author or creator; its format, genre, publication history; or related materials in a collection.

4D. As part of the analysis of available resources, identify, interrogate, and consider the reasons for silences, gaps, contradictions, or evidence of power relationships in the documentary record and how they impact the research process.

- Assessment

- Conduct an assessment using a handout which asks the following questions:

- What can a person learn about hip hop through examining a primary source object?

- How confident would you feel in analyzing another primary source object from the Houston Hip Hop Research Collection?

- Format of material used

- Flyer

- Procedure

- Introduce yourself and your positionality, especially as it pertains to hip hop.

- Describe the founding of the Houston Hip Hop Research Collection at the University of Houston Libraries in 2010 as an approach for preserving the music and culture of Houston hip hop. Discuss the concept of archival silences and ask why hip hop might not have been collected in institutional archives until the 2000s. Ask students which people might influence how hip hop is collected, described, and made accessible in archives, and discuss mediation by donors, collectors, and archivists. Introduce the alternative of community-driven hip hop archives and museums.

- Conduct an assessment using a handout which asks the following questions:

- (Optional) Invite the class to brainstorm terms that relate to hip hop (examples of responses might be: underground, mainstream, political, feminist, conscious, gangsta, Afrocentric).

- Ask students to analyze a flyer from the Carlos “DJ Styles” Garza Papers using the following prompts provided in a worksheet. Ideally, students will work with a physical printout of one of the flyers, but the session would also work with a digital image of a flyer projected in the classroom or accessible on a computer. Consider putting students in pairs or small groups for this activity.

- What is the object you are examining? Who is the creator? Where and when was it created?

- Who is the intended audience for the object?

- Describe the physical characteristics of the object. Is it handwritten? Typed? What kind of paper is it on?

- Does it have visual design elements? How do they relate to the rest of the object?

- Does the object convey a particular stance or image to the audience?

- (Optional) Choose a few of the previously brainstormed terms that best describe the object.

- Describe how your own personal experiences or observations of hip hop help you (or do not help you) to understand the object.

- Ask a sample of the students or groups to present their analyses to the rest of the class.

- Lead students in a wrap-up discussion of the following questions:

- Hip hop is still a fairly new thing to be found in an archive. Do you think hip hop music and culture belongs in an archive? Why or why not?

- What else could be collected in an archive other than hip hop that would document the contemporary Black experience or the contemporary Latinx experience?

Appendix 1. Playlist Created by Carlos Garza

LL Cool J, “Rock the Bells,” track 7 on Radio, Def Jam Recordings, Columbia Records, 1985, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/4F4neui0edP1ozygvFiCi7.

Whodini, “Friends,” track 6 on Escape, Jive Records, 1984, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/2GLDYbNCRgsZTBhrBqhdm0.

Rob Base & DJ E-Z Rock, “It Takes Two,” track 1 on It Takes Two, Profile Records, 1988, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/0gFB5H3pHN13ERt2FyMuWi.

MC Shan, “The Bridge,” Down by Law, Cold Chillin’, 1987, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/7pb9gOx7XsGQwpZlU5p6LF.

Run DMC, “Run’s House,” track 1 on Tougher than Leather, Profile Records, 1988, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/42kFZZo0w4UeAJVt5N9yTw.

EPMD, “You Gots to Chill,” track 4 on Strictly Business, Fresh/Sleeping Bag Records, 1988, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/0f1yzIIGD8k32DNVeEn6jb.

Mantronix, “Fresh is the Word,” track 7 on The Album, Sleeping Bag Records, 1985, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/2l4ePynIXB1ZfsbMHjYA3a.

Stetsasonic, “Sally,” track 12 on In Full Gear, Tommy Boy, 1988, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/1uaMmbCmOKkI1dg4yjosH6.

Eric B. and Rakim, “Eric B. is President,” track 9 on Paid in Full, 4th & B’way Records, 1987, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/3a8r3EYOFZB7cT1OkK4zXF.

Salt-N-Pepa, “Push It,” track 1 on Hot, Cool & Vicious, Next Plateau, 1986, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/6sT9MWlJManry3EQwf4V80.

Public Enemy, “Rebel Without a Pause,” track 14 on It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, Def Jam Recordings; 1988, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/5lWwAQUep9RKuwtSJY41ab.

Rodney O & Joe Cooley, “Ever Lasting Bass,” track 10 on Me and Joe, Egyptian Empire, 1995, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/7ELrZXew8UFNWyCHZF47ED.

Big Daddy Kane, “Ain’t No Half Steppin’,” track 6 on Long Live the Kane, Cold Chillin’ Records, 1988, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/0dNiLb9FEHrRK7VFDJctiR.

Biz Markie, “Make the Music with your Mouth, Biz” track 1 on Make the Music with your Mouth, Biz, Prism Records, 1986, MP3. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/track/7LJrtz3AXHb1G1BM1YevO5.

Endnotes

[1] Dave Ellenwood and Alyssa Berger, “Fresh Techniques: Hip Hop and Library Research,” in Critical Library Pedagogy Handbook: Lesson Plans, eds. Nicole Pagowsky and Kelly McElroy (Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries, 2016), 197–205.

[2] Cheryl Lederle, “Core Strategies for Working with Primary Sources: Primary Source Analysis,” accessed February 8, 2023, https://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/2020/04/core-strategies-for-working-with-primary-sources-primary-source-analysis/, archived December 8, 2023 at https://web.archive.org/web/20230608110914/https://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/2020/04/core-strategies-for-working-with-primary-sources-primary-source-analysis/.

[3] “Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy” ACRL RBMS-SAA Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/standards/Primary%20Source%20Literacy2018.pdf, archived September 30, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230930012216/https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/standards/Primary%20Source%20Literacy2018.pdf.

[4] Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1994): 193, Kindle; Felicia M. Miyakawa, “Hip Hop,” Grove Music Online, 10 July 2012, accessed 30 June 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2224578

[Grove Music Online is only available by subscription. It may be available through academic or other research libraries].

[5] Maco L. Faniel, Hip-Hop in Houston: The Origin & the Legacy (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013), 37–40.

[6] Faniel, Hip-Hop in Houston, 85.

[7] Carlos “DJ Styles” Garza, interview with Donnie Houston, The Donnie Houston Podcast, podcast audio, 2020, https://soundcloud.com/thedonniehoustonpodcast/episode-80-soundwaves-feat-carlos-dj-styles-garza.

[8] Faniel, Hip-Hop in Houston, 85.

[9] Lance Scott Walker, Houston Rap Tapes: An Oral History of Bayou City Hip-Hop (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 129.

[10] Katherine A. Reagan, “The Cornell Hip Hop Collection: An Example of an Archival Repository,” Global Hip Hop Studies 1, no. 1 (June 2020): 149–50, https://doi.org/10.1386/ghhs_00009_1.

[11] Reagan, “Cornell Hip Hop Collection,” 153.

[12] Amanda Lalonde, “Buddy Esquire and the Early Hip Hop Flyer,” Popular Music 33, no. 1 (2014): 19, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143013000512.

[13] Jeff Chang, “Flipping the Script: Beyond the Four Elements,” in Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip Hop, ed. J. Chang (New York: BasicCivitas Books), 55.

[14] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Thirtieth Anniversary Edition (New York: Continuum, 2000), 79–81.

[15] Carlos Garza, text message to the author, November 21, 2023.