12 Health Equity

Elizabeth B. Pearce; Amy Huskey; Jessica N. Hampton; Hannah Morelos; Alexis Castaneda-Perez; and Joyce Baptist

Health in the United States is a complex topic. On the one hand, as one of the wealthiest nations, the United States fares well in some health comparisons with the rest of the world. “However, in 2023, Americans had a life expectancy of 78.4 years, compared to an average of 82.5 among peer countries. This chart collection examines deaths in the U.S. and comparable countries through 2021, by age group and cause, to highlight factors that contribute to this life expectancy gap. ” [1]

What drives differences in life expectancy between the U.S. and comparable countries?

The overall comparative picture is more grim. The United States spends a great deal more public, private, and out-of pocket funds per capita on health care[2] but also lags behind almost every industrialized country in terms of providing basic health and health care to all of its citizens.

“Many adults face barriers accessing medical care. High cost-sharing and expenses not covered by insurance leave some with expensive medical bills. Many adults face additional barriers accessing needed healthcare. Long appointment wait times, difficulty finding in-network providers and challenges traveling to providers at convenient times may lead some to delay or skip care.” [3]

Beyond cost, what barriers to health care do consumers face?

But these charts do not tell the entire story. Within the United States, groups are affected disproportionately in terms of access to health and health outcomes. These disparities are described next.

Disparities

Health disparities are preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations [4]. These populations are often defined by race, ethnicity, gender, education, income, disability, geographic location, or sexual orientation. Health disparities are inequitable and stem from both historical and ongoing unequal distribution of social, political, economic, and environmental resources [5].

Current research highlights that health disparities result from a complex interplay of factors, including:

- Poverty

- Environmental threats

- Inadequate access to health care

- Individual and behavioral factors

- Educational inequalities [6].

Education remains a critical determinant of health. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, individuals with higher levels of education tend to live longer, earn more, and are better equipped to understand and act on health information [7]. Conversely, dropping out of school is associated with increased risks of obesity, substance abuse, and injury. These risks are more prevalent among individuals with lower educational attainment, reinforcing cycles of disadvantage [8].

Moreover, academic success and health are mutually reinforcing. The CDC reports that students who engage in protective health behaviors—such as regular physical activity, healthy eating, and avoiding substance use—tend to earn higher grades and have better attendance. In contrast, health risks like teenage pregnancy, poor nutrition, emotional abuse, and gang involvement significantly impair academic performance and long-term educational outcomes [9].

These findings underscore the importance of integrated approaches to health and education. Addressing health disparities requires not only improving access to care but also investing in education, community support, and policies that promote equity across all domains of life.

Health by Race and Ethnicity

When examining the social epidemiology of the United States, racial disparities in health outcomes remain stark. Although overall life expectancy has improved for both Black and White Americans over the past several decades, significant gaps persist. A comprehensive 70-year study found that while life expectancy for Black Americans rose from 60.5 years in the 1950s to 76 years in the 2010s, and for White Americans from 69 to 79.3 years, Black adults still face an 18% higher mortality rate [10] .

The disparity is even more pronounced in infant mortality. In 2022, the infant mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black infants was 10.9 per 1,000 live births, compared to 4.5 for non-Hispanic White infants, making Black infants 2.4 times more likely to die in their first year [11].

Causes of death such as low birthweight, sudden infant death syndrome, and maternal complications were significantly more prevalent among Black infants. These disparities are compounded by systemic issues such as delayed prenatal care, which Black mothers were more than twice as likely to experience compared to White mothers [12].

Ethnic minorities—including Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander populations—also experience higher rates of chronic diseases and mortality. For example, AIAN individuals had a life expectancy of 67.9 years in 2022, compared to 77.5 years for White individuals[13].

Lisa Berkman, a leading social epidemiologist, notes that while the racial health gap narrowed during the Civil Rights movement, it began widening again in the 1980s due to structural inequalities in healthcare access and quality [14]. Even after adjusting for insurance status, racial and ethnic minorities consistently receive lower quality care and have less access to healthcare services than White Americans.

Recent data show:

- Black, Native American, and Alaskan Native patients received inferior care compared to White patients for approximately 40% of healthcare measures.

- Asian American patients received inferior care for about 20% of measures.

- Hispanic White patients received 60% inferior care compared to non-Hispanic Whites

[15].

These disparities in both access and quality of care reflect deeply entrenched systemic inequities. Addressing them requires not only policy reform but also a commitment to equity in healthcare delivery, education, and community support.

Health by Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Discussions of health by race and ethnicity often overlap with those of socioeconomic status (SES), as the two are deeply intertwined in the United States. According to the JAMA Health Forum, racial and ethnic minorities are significantly more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to experience poverty, limited access to healthcare, and environmental disadvantages—all of which contribute to poorer health outcomes [16]. These overlapping disadvantages are central to understanding persistent health disparities.

Research continues to affirm that socioeconomic status is one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of morbidity and mortality. A recent study using four nationally representative datasets confirmed that individuals with lower income and education levels consistently reported worse health outcomes across all racial and ethnic groups [17]. These disparities persist across the lifespan and are evident in both self-rated health and objective measures such as obesity and chronic disease prevalence.

Importantly, education plays a critical role in shaping health outcomes. Phelan and Link’s fundamental cause theory explains that SES influences health not just through material resources, but through access to flexible resources like knowledge, power, and social connections that can be used to avoid disease or mitigate its effects [18]. For example, when new health information becomes available—such as the link between smoking and lung cancer—higher SES groups are more likely to adopt protective behaviors, leading to widening health gaps over time.

This pattern is evident in diseases like coronary artery disease and HIV/AIDS, where early public health messaging and interventions were more effectively adopted by higher SES populations. As a result, these diseases have declined in those groups while remaining prevalent in lower SES communities, illustrating how health education and access to information are not equally distributed [19].These findings underscore the importance of addressing both economic and educational inequalities in public health strategies. Without targeted interventions that account for the structural barriers faced by marginalized communities, health disparities will continue to persist—even as medical knowledge and technology advance.

Health by Gender

Women continue to face systemic barriers in the U.S. healthcare system, including unequal access and institutionalized sexism. Recent data show that 15.6% of women aged 18 and older report being in fair or poor health, and 7.7% of women under 65 remain uninsured, despite policy efforts to expand coverage [20]. These disparities are even more pronounced among women of color, with Black women experiencing maternal mortality rates over three times higher than white women (50.3 vs. 14.5 deaths per 100,000 live births) [21].

Intersectionality theory, developed by feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins, provides a critical lens for understanding how overlapping identities—such as race, gender, class, and sexual orientation—compound disadvantage [22]. This framework helps explain why low-income women are significantly more likely to express concerns about healthcare quality, as multiple layers of marginalization shape their experiences.

Institutionalized sexism is also evident in mental health diagnoses. Women are disproportionately diagnosed with certain disorders, such as Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), which affects women at a rate of 75% of all cases. Recent data show that adult females are 1.8 times more likely than males to be diagnosed with depression and 2.5 times more likely to report symptoms of major depressive episodes in youth [23]. Critics argue that these patterns reflect gender bias in diagnostic criteria and clinical practice, often tion and pregnancy to menopause and aging—remains a significant concern. A 2025 qualitative study found that both physicians and women view medicalization as driven by societal beauty standards, media influence, and institutional norms. Women reported feeling pressured into unnecessary medical interventions, especially during childbirth and aesthetic procedures [24]. The study also highlighted that social support during childbirth was as effective as medical intervention in reducing pain and postpartum depression, yet access to such support varies widely by socioeconomic status.

Efforts to address these disparities must include inclusive healthcare environments, ongoing provider education, and policies that reflect the lived experiences of women with intersecting marginalized identities. A 2025 study emphasized the importance of affirming care for LGBTQ+ individuals, noting that discrimination in healthcare settings leads to delayed treatment, mistrust, and poorer health outcomes. [25].

Interrelationship of Mental and Physical Health

Mental and physical health have been socially constructed in the Western world to be viewed as separate, with mental disorders being stigmatized. Often mental illnesses such as depression or anxiety have been seen as something that a person should and could “get over” as opposed to a physical ailment such as a sprained ankle or strep throat that merits medical attention and assistance. Even physical illnesses such as fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome, which are experienced by many more women than men, can be seen as “in the patient’s head” leading to the potential miss of physical illnesses that need medical intervention. This leaves the patient with not only the physical symptoms, but also a potential lack of understanding amongst peers, family members, medical professionals, and co-workers.

Eastern and Native cultures have long seen the connection between the mind and body and indeed, this connection is better understood in the United States and among other Western countries today. Cancer, heart and respiratory disease death rates are all higher in people with mental illness. In addition, it is better understood how physical lifestyle choices such as exercise, diet, and drug use affect mental health and visa versa.[26] To read more about the relationship between physical and mental health, PsychCentral has a brief article here.

Stigma

An example of the relationship between mental health and stigma includes a person struggling with depression which results in a physical symptom of weight gain or weight loss due to a lack of appetite or excessive hunger. Obesity and excessive thinness are both stigmatized in our culture, while the underlying mental or physical health condition may be ignored. Mental health disorders are treated and looked at differently than health struggles on a more physical level. Although we have seen a shift in media about mental illness from known celebrities coming forward, there is still a social stigma against mental health. Oftentimes when someone is diagnosed with a physical illness such as cancer or heart disease we see communities and families coming together. Unfortunately, we rarely see mental illness struggles come to the surface without holding a place of shame or guilt; individuals, families and communities are often more reluctant to talk about and come together in the same way.

When we speak about stigma we speak of there being two different types: the first stigma is the social stigma meaning the prejudiced attitudes others have around mental illness and the treatment of mental illness. The second one being self-perceived stigma which is an internalized stigma that the individual who suffers from the mental illness has. Not only does the stigma around mental illness create painful emotions and a sense of invalidation for the individual, it can result in a reluctance to seek treatment, social rejection, avoidance, isolation, and direct harm to psychological well-being. The socially and self-perceived stigma attached to mental illness can be reinforced by common cultural misconceptions, social stereotypes, popular media representations, political leaders, and even some medical professionals and health care institutions.

Health Insurance Coverage and Legislation

Like all other health care in the United States, access to mental health care remains closely tied to access to health insurance. Historically, mental health support has not been recognized or prioritized to the same extent as physical health, leading insurance companies and government programs to exclude or limit mental health coverage in ways that physical health coverage was not.

This disparity began to shift with two major legislative acts: the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010. MHPAEA required that if mental health services were offered, they must be provided on par with physical health services. However, it did not mandate that insurers offer mental health coverage at all, leaving significant gaps in access depending on state laws and individual insurance plans.

The ACA made more substantial strides by requiring insurers to cover mental health and substance use disorder services as one of ten essential health benefits, and by prohibiting denial of coverage due to pre-existing conditions. These changes expanded access, but disparities persisted.

In September 2024, the Biden administration finalized new rules under MHPAEA to further strengthen parity between mental health/substance use disorder (MH/SUD) benefits and medical/surgical (M/S) benefits. These rules prohibit discriminatory practices in insurance design, require insurers to evaluate and correct disparities in access, and mandate comparative analyses to ensure mental health benefits are not more restrictive than physical health benefits. They also expand coverage requirements to include previously exempt non-federal government health plans, affecting over 120,000 additional consumers [27].

Despite these improvements, access remains uneven. According to the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 23.4% of U.S. adults experienced a mental illness, yet only a fraction received adequate treatment. Among the 52.6 million individuals who needed substance use treatment, only 10.2 million received it [28]. Barriers include stigma, cost, lack of provider availability, and insufficient insurance coverage.

These reforms mark progress, but they primarily benefit families with access to qualifying insurance plans. Many Americans—especially those in marginalized communities—still face significant obstacles to receiving timely, affordable, and culturally competent mental health care.

In Focus: Sleep, Discrimination and Intersectionality

Let’s focus on how these various disparities overlap with everyday behavior. A biological need that is fundamental to human health is sleep, yet the medical community still has much to understand and learn about its exact mechanisms. Sleep is a vital part of our daily routine, and we spend about one-third of our time doing it. Quality sleep, and getting enough of it at the right times, is as essential to survival as food and water. In rats, death results from no sleep at 32 days.[29] Research has not observed human death as a result of prolonged sleep deprivation, but paranoia and hallucinations can begin happening in as little as 24 hours without sleep.[30]

Without sleep you can’t form or maintain the pathways in your brain that let you learn and create new memories, and it’s harder to concentrate and respond quickly. Sleep is important to a number of brain functions, including how nerve cells communicate with each other. In fact, our brains and bodies stay remarkably active while we sleep. Recent findings suggest that sleep plays a housekeeping role that removes toxins in our brains that build when we are awake.

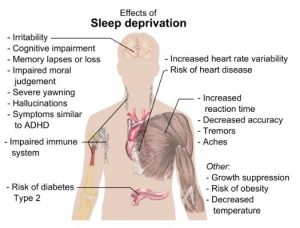

Sleep affects almost every type of tissue and system in the body, from the brain, heart, and lungs to metabolism, immune function, mood, and disease resistance. Research shows that a chronic lack of sleep, or getting poor quality sleep, increases the risk of disorders including high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, and obesity. All of these conditions would likely have a noticeable effect on multiple dimensions of family life and how it impacts the well being of a family as a whole.

For some surprising and specific health effects of sleep view this TED Talk:

In 2025, research continues to affirm that sleep disparities in the United States are strongly associated with race, ethnicity, poverty, and other social determinants of health. A recent study published in JAMA Network Open found that individuals from racially minoritized and socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds experience significantly worse sleep trajectories, which are linked to increased mortality risk [31]. These disparities are not merely biological but are shaped by structural inequities such as neighborhood conditions, chronic stress, and limited access to health care.

A comprehensive review in Current Sleep Medicine Reports emphasized that sleep disparities are driven by multi-level social determinants, including discrimination, environmental stressors, and economic instability[32]. For example, individuals living in noisy or unsafe neighborhoods, working irregular shifts, or experiencing systemic racism are more likely to suffer from poor sleep quality. These factors often intersect—particularly for low-income families and communities of color—compounding the effects on sleep and overall health.

The National Sleep Foundation’s 2025 Sleep in America Poll further supports the bidirectional relationship between sleep and health. Adults with poor sleep health reported significantly lower levels of happiness, productivity, and social fulfillment. The poll found that 39% of adults with poor sleep health felt their social lives were unfulfilling, compared to only 17% of those with good sleep health [33]). This illustrates how sleep quality not only reflects health status but also influences emotional well-being and family dynamics.

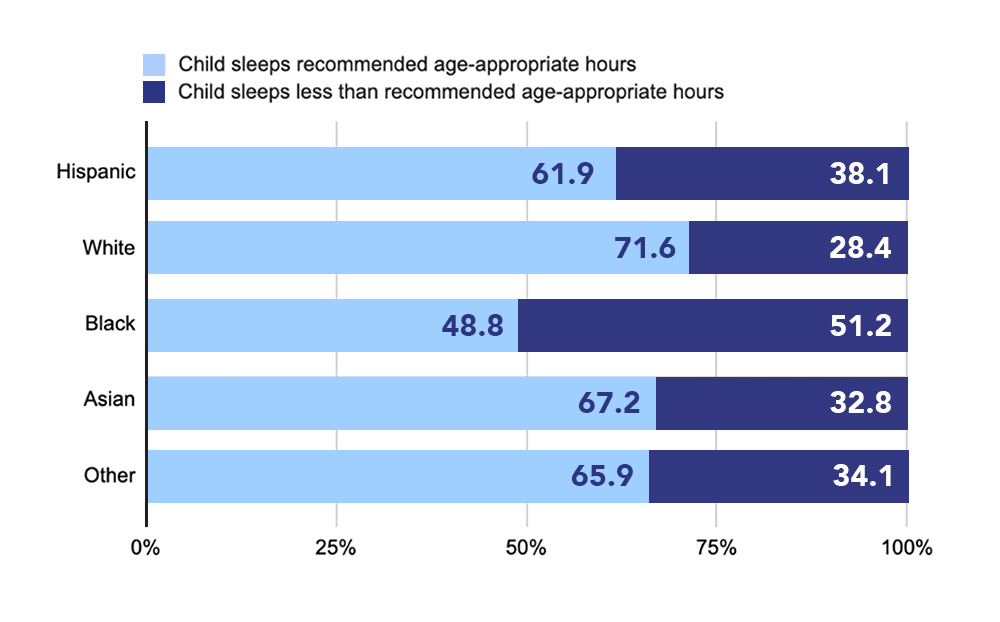

Importantly, the relationship between sleep and health is bidirectional and parallel—poor health increases the likelihood of poor sleep, and poor sleep exacerbates health conditions. These findings underscore the need to address sleep disparities as part of broader efforts to promote health equity. Less than half (48.8 percent) of Black children sleep the recommended age-appropriate hours, whereas 71.6 percent of White children sleep the recommended amount (National Survey of Children’s Health, 2022-2023).

Figure 3.5 Sleep Inequity by Race

Similarly discrimination, and intersectional discrimination in particular, appear to influence sleep, mental, and physical health. The relationship between discrimination amongst populations such as women, racial and ethnic minorities, and members of the LGBTQ+ groups with poorer mental and physical health has been established. For instance, discrimination can harm wellbeing, increase distress and mental illness symptoms, elevate risk for a wide variety of physical illnesses and conditions, and undermine general indicators of health.[34][35] Recently, the lack of sleep and less functionality during the daytime have been identified as integral aspects of the cycle of discrimination, stress, and overall mental and physical health.[36]

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Disparities” is adapted from “Health Disparities” by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public domain. [Adaptation: ?]

“Health by Race and Ethnicity,” “Healthy by Socioeconomic Status,” and “Healthy by Gender” are adapted from “Health in the United States” in Introduction to Sociology 2e. License: CC BY 4.0. [Adaptation: ?]

“In Focus: Sleep, Discrimination and Intersectionality” is adapted from “Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep” by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke / National Institute of Health. Public domain. Adaptations: Changed just a few words and changed some hyphens to commas.

Figure 3.3. “Right on” by LizSpikol. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 3.4. “Main health effects of sleep deprivation” by Mikael Häggström. CC0.

Figure 3.5. “Sleep Inequity by Race.” Source: The Data Behind Childhood Bed Poverty is Dire.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Sleep is your superpower” (c) TED Talks. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

- Shanosky, N., McDermott, D., & Kurani, N. (2020, August 12). What drives differences in life expectancy between the U.S. and comparable countries? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. ↵

- Tikkanen, R. & Abrams, M.K. (2020, January 30). U.S. health care from a global perspective, 2019: Higher spending, worse outcomes? The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019 ↵

- Telesford, I., Winger, A., & Rae, M. (2024, August 22). Beyond cost, what barriers to health care do consumers face? Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2022). Resolution on poverty and socioeconomic status. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/poverty-resolution ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2025). APA policy statement on the benefits of inclusivity to psychology and higher education. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/benefits-inclusivity-higher-education.pdf ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2022). Resolution on poverty and socioeconomic status. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/poverty-resolution ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2025). APA policy statement on the benefits of inclusivity to psychology and higher education. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/benefits-inclusivity-higher-education.pdf ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2022). Resolution on poverty and socioeconomic status. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/poverty-resolution ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, July 18). Health and academics. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/healthy-schools/health-academics/index.html ↵

- Paternina-Caicedo, A., Espinosa, O., Sheth, S., Hupert, N., & Saghafian, S. (2025). Excess mortality rate in Black children since 1950 in the United States: A 70-year population-based study of racial inequalities. Annals of Internal Medicine, 178(4), 490–497. https://tinyurl.com/2czazhso ↵

- CDC, 2024. Infant Mortality in the United States, 2022: Data from the Period Linked Birth/Infant Death File. National Vital Statistics Reports, vol. 73 ↵

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2024, October 25). Racial disparities in maternal and infant health: Current status and efforts to address them. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/ ↵

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2024). What is driving widening racial disparities in life expectancy? Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/what-is-driving-widening-racial-disparities-in-life-expectancy/ ↵

- Berkman, L. F. (2000). Social support, social networks, social cohesion and health. Social Work in Health Care, 31(2), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1300/J010v31n02_02 ↵

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2024). What is driving widening racial disparities in life expectancy? Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/what-is-driving-widening-racial-disparities-in-life-expectancy/ ↵

- Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., & Davis, B. A. (2023). Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. JAMA Health Forum, 4(1), e225430. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.5430 ↵

- Zajacova, A., Montez, J. K., & Hummer, R. A. (2023). Education and health disparities in the United States: Patterns and explanations. Annual Review of Public Health, 44, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-100018 ↵

- Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2015). Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305 ↵

- Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2015). Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305 ↵

- The Global Statistics (2025) – U.S. Women’s Health Statistics ↵

- The Global Statistics (2025) – U.S. Women’s Health Statistics ↵

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality (2nd ed.). Polity Press. ↵

- America’s Health Rankings (2025) – Gender disparities in mental health diagnoses ↵

- Kırlı & Kaya (2025) – BMC Health Services Research on medicalization of female life stages. ↵

- Singh et al. (2025) – BMC Health Services Research on affirming care for LGBTQ+ individuals. ↵

- Mental Health Foundation. (2020). Physical health and mental health. Retrieved July 3, 2020, from https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/p/physical-health-and-mental-health ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2024, September 10). APA Services pushed for new rule strengthening mental health care access. https://www.apa.org/news/apa/2024/mental-health-parity-rule ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2025). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP25‑07‑007, NSDUH Series H‑60). https://library.samhsa.gov/product/2024-nsduh-report/pep25-07-007 ↵

- Palmer, B. (2009, May 11). Can you die from lack of sleep? Slate. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2009/05/can-you-die-from-lack-of-sleep.html ↵

- Waters, F., Chiu, V., Atkinson, A., & Blom, J. D. (2018). Severe sleep deprivation causes hallucinations and a gradual progression toward psychosis with increasing time awake. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 303. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.003 ↵

- Johnson, D. A., et al. (2025). Racial and socioeconomic differences in sleep duration trajectories and mortality risk. JAMA Network Open, 8(2), e2462127. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2830791 ↵

- White, K. M., et al. (2025). Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance sleep health equity in the United States: A blueprint for research, practice, and policy. Current Sleep Medicine Reports, 11, Article 30. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40675-025-00339-7 ↵

- National Sleep Foundation. (2025). Sleep in America Poll. https://www.thensf.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/NSF_SIA_2025-Report_final.pdf ↵

- Brown, T. T., Partanen, J., Chuong, L., Villaverde, V., Chantal Griffin, A., & Mendelson, A. (2018). Discrimination hurts: The effect of discrimination on the development of chronic pain. Social Science & Medicine, 204, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.03.015 ↵

- Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921–948. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035754 ↵

- Hisler, G. C., & Brenner, R. E. (2019). Does sleep partially mediate the effect of everyday discrimination on future mental and physical health? Social Science & Medicine, 221, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.002 ↵