13 Health and Health Insurance

Elizabeth B. Pearce; Jessica N. Hampton; Christopher Byers; and Joyce Baptist

Industrial nations throughout the world, with the notable exception of the United States, provide their citizens with some form of national health care and national health insurance.[1] Although their health-care systems differ in several respects, their governments pay all or most of the costs for health care, drugs, and other health needs. In Denmark, for example, the government provides free medical care and hospitalization for the entire population and pays for some medications and some dental care. In France, the government pays for some of the medical, hospitalization, and medication costs for most people and all these expenses for the poor, unemployed, and children under the age of ten. In Great Britain, the National Health Service pays most medical costs for the population, including medical care, hospitalization, prescriptions, dental care, and eyeglasses. In Canada, the National Health Insurance system also pays for most medical costs. Patients do not even receive bills from their physicians, who instead are paid by the government. These national health insurance programs are commonly credited with reducing infant mortality, extending life expectancy, and, more generally, for enabling their citizenries to have relatively good health. Their populations are generally healthier than Americans, even though health-care spending is much higher per capita in the United States than in these other nations. In all these respects, these national health insurance systems offer several advantages over the health-care model found in the United States.[2]

The Role of Health Insurance in the United States

Medicine in the United States is big business. Expenditures for health care, health research, and other health items and services have risen sharply in recent decades, having increased tenfold since 1980, and projected to spend $5.96 trillion on healthcare in 2027. [3] This translates to the largest figure per capita in the industrial world.

Access to Health Care Coverage and Insurance

There are many insurance options in America, and they continue to disproportionately benefit some and disadvantage others based on factors like sex, income, geographical location, and ethnicity. As of 2024, private insurance remains the dominant form of coverage, protecting 65.4% of Americans under age 65, while public insurance programs such as Medicaid, Medicare, and CHIP serve 26.6% of the same population. [4] Despite improvements, 27.2 million Americans—or 8.2% of the population—remain uninsured, with Hispanic adults experiencing the highest uninsured rate at 24.6%, followed by Black adults (10.5%), White adults (7.9%), and Asian adults (5.4%).

Recent legislation, such as the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Act, is expected to significantly reshape access to health insurance. The law introduces new eligibility requirements and spending cuts, including a federal work requirement for Medicaid recipients starting in 2027, which may result in up to 15 million more people losing coverage by 2034. [5]

To learn more about how people accessed health insurance coverage, and who remained uncovered watch this seven-minute video provided by the United States Census Bureau.

Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), enacted in 2010, marked a historic expansion of civil rights protections in healthcare by prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, and disability in any health program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. This provision was further strengthened by the 2016 Final Rule, which clarified enforcement mechanisms and extended protections to include gender identity and sex stereotyping

The updated rule also addresses intersectional discrimination, recognizing that individuals may face compounded biases based on multiple protected characteristics, such as race and disability or gender identity and age. [8] It mandates that covered entities—such as hospitals, insurers, and clinics—implement policies and training to ensure compliance, including the appointment of a Section 1557 Coordinator and the publication of nondiscrimination notices by November 2, 2024 [9] These entities must also ensure accessibility in telehealth services and the use of artificial intelligence tools in clinical decision-making, preventing discriminatory outcomes .

Insurance for Lower Income Families

Lower-income families and individuals across the United States commonly access health insurance through government programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Medicaid is jointly funded by federal and state governments but administered by individual states, which have flexibility in determining eligibility criteria and benefits. While most states focus on covering low-income individuals, children, pregnant women, and people with disabilities, eligibility and coverage details vary by state [10] CHIP complements Medicaid by providing coverage to children in families with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to afford private insurance.

Following the Affordable Care Act (ACA) expansion in 2014, states were given the option to expand Medicaid to cover nearly all adults earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level. As of 2025, 41 states and the District of Columbia have adopted Medicaid expansion, while 10 states have not [11] Additionally, recent federal policies have strengthened CHIP coverage, requiring all states to implement 12-month continuous eligibility for children starting in 2024, and encouraging multi-year eligibility through Section 1115 waivers [12] States have also taken steps to eliminate premiums and reduce enrollment barriers, with several expanding coverage to immigrant children regardless of status

For detailed, up-to-date information on Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and expansion status in each state, consult the Kaiser Family Foundation’s interactive map and state fact sheets, consult this Kaiser Family Foundation interactive map and narrative.

Figure 3.6 Coverage Gap for Adults

The variance in Medicaid eligibility creates great inequity for low-income families based on location. Those in states that have not expanded Medicaid face a much larger “coverage gap” meaning that many more families do not have access to health care insurance.

Insurance for Older Adults

Individuals aged 65 and older are eligible for Medicare, a federally funded health insurance program that covers a wide range of healthcare services. While Medicare provides essential coverage, it typically pays for about 50–60% of total healthcare expenses for enrollees. [13]. To manage out-of-pocket costs, many beneficiaries opt for supplemental coverage, which may include Medicare Advantage (Part C) plans, Medigap policies, or employer-sponsored retiree insurance. [14] Medicare Advantage plans often offer additional benefits such as dental, vision, and wellness services, and their enrollment continues to grow nationwide [15]

For those not enrolled in Medicare Advantage, Medicare Part D helps cover prescription drug costs, though many still face significant cost-sharing responsibilities. As healthcare needs increase with age, retirees who can afford to do so often purchase private insurance or supplemental plans to fill coverage gaps and reduce financial risk.[16]

Case of Medical Induced Bankruptcy:

Who is Left Out?

Fig. 3.7. The patchwork of insurance, government programs and laws, and private payments inequitably affects lower income peopleAs of 2023, most uninsured individuals in the United States are working-age adults between 19 and 64 years old, accounting for the vast majority of the uninsured population [17] Despite women outnumbering men in the general population, men remain overrepresented among the uninsured, with working-age men having higher uninsured rates than women in over 60% of U.S. counties.

Socioeconomic factors—including occupation, education level, and chronic poverty—play a major role in determining access to healthcare. Populations such as children, older adults, and people of color are disproportionately affected by gaps in coverage and care. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) continues to document disparities in healthcare access and outcomes, noting that individuals from lower-income households and marginalized racial and ethnic groups experience higher rates of being uninsured and face greater barriers to care [21]

A recent analysis of health insurance coverage in the United States shows that racial and ethnic disparities persist despite improvements following the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Before the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in 2014, uninsured rates were significantly higher among communities of color—approximately 41% of Hispanics, 26% of Black Americans, and 15% of White Americans lacked coverage [22] Post-expansion, these rates declined, but gaps remain. In 2023, the uninsured rate for Hispanic individuals was 17.7%, compared to 9.3% for Black individuals and 5.7% for White, non-Hispanic individuals [23] These disparities are compounded by geographic inequities: eligibility for Medicaid varies widely by state, with income thresholds ranging from 40% to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), meaning a family poor enough to qualify in one state may not be eligible in another [24]

Socioeconomic status—including education, occupation, and chronic poverty—continues to influence access to healthcare. Even among individuals with higher educational attainment, racial disparities in insurance coverage persist. For example, non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native adults with a college degree had uninsured rates more than three times higher than their White counterparts [25]

The consequences of being uninsured are severe. Individuals without health insurance are less likely to receive preventive care, such as cancer screenings, and more likely to be diagnosed at later stages of illness. This delay in diagnosis contributes to worse health outcomes and higher mortality rates. Prior research has shown that uninsured adults aged 17 to 64 face a 25% higher risk of death compared to those with private insurance [26]

Research and Drug Access

Pharmaceutical research and sales remain a massive industry in the United States, with the cost of developing a single new drug now estimated to exceed $2.3 billion, factoring in both direct R&D expenses and the cost of failures along the way

While private pharmaceutical companies fund much of the late-stage development and commercialization, early-stage discovery research is still heavily supported by federal agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), as well as philanthropic organizations

Later stage development is typically funded by pharmaceutical companies, which can be for for-profit companies or nonprofit companies. For-profit companies may be funded by venture capitalists or as a part of larger corporations. Funding for nonprofit companies is a bit trickier; gaining access to federal and foundation funding takes staff time and expertise. The unequal and inequitable funding opportunities put not-for-profits at a disadvantage, because they have to invest more time in writing requests for grants and funding from government corporations.

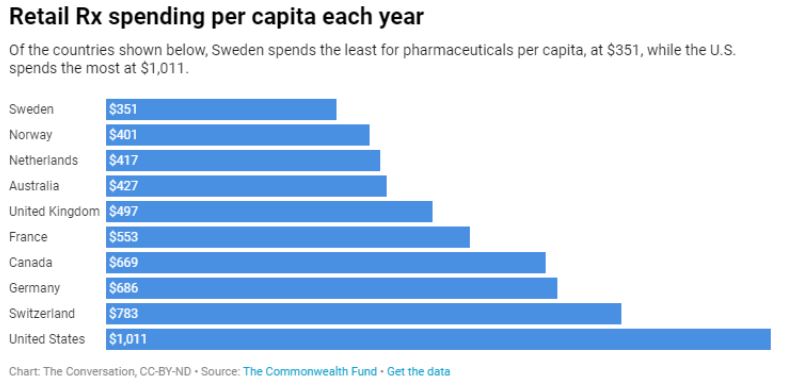

The cost of drugs in the United States increased dramatically starting in the 1990s. It is important to note that American families are not accessing more medications than people in comparative countries. In fact, Americans use fewer prescription drugs and are more likely to use less expensive generic prescriptions. It really comes down to price per pill; they simply cost more in the United States than in other countries.[31]

For-profit pharmaceutical companies continue to wield significant influence over drug distribution, pricing, and research priorities in the United States. While these companies play a crucial role in late-stage development and commercialization, their profit-driven models can create ethical tensions—particularly when shareholder interests conflict with public health needs. This dynamic raises concerns when life-saving medications are priced beyond the reach of those who need them most. Unlike many other high-income countries, the U.S. does not impose direct price controls or negotiate national drug prices for most medications. In contrast, countries such as France, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom maintain tighter government oversight and often negotiate state contracts with pharmaceutical firms to keep costs low and ensure equitable access [32]

The U.S. model relies heavily on market forces, which can lead to high launch prices for new drugs and limited affordability for uninsured or underinsured populations. Although recent legislation—such as the Inflation Reduction Act—has introduced Medicare drug price negotiations, broader systemic reforms are still needed to balance innovation incentives with public health equity [33]

In Focus: The Opioid Epidemic

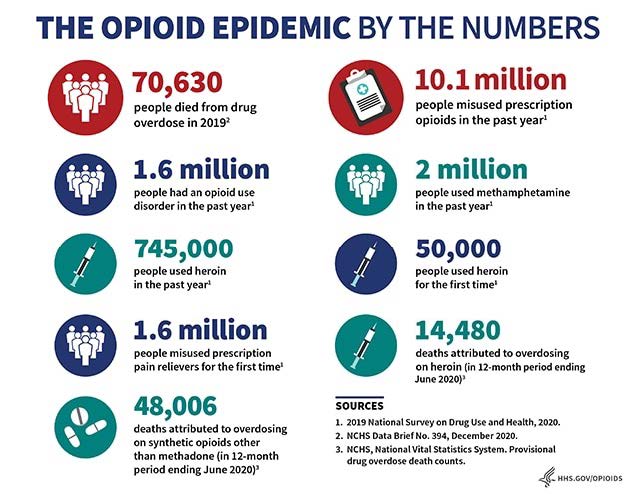

Families across the United States continue to struggle with access to effective and safe pain management, and for many, opioids have been a widely used—though often problematic—solution. The liberal prescribing of opioid medications began in the mid-20th century and escalated dramatically in the 1990s, when pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed these drugs and assured healthcare providers that they posed minimal risk of addiction [34] This misinformation contributed to a surge in prescriptions for both acute and chronic pain, often without adequate oversight or patient education.

It is now well-established that opioid addiction frequently begins with prescription medications. Many individuals who become dependent on opioids start with legally prescribed drugs and, over time, may transition to illicit substances such as heroin or fentanyl if their access is restricted or their tolerance increases [35] The opioid epidemic has evolved into a complex public health crisis, prompting federal and state agencies to implement prevention, treatment, and harm-reduction strategies. Despite these efforts, overdose deaths—particularly those involving synthetic opioids—remain alarmingly high, underscoring the need for continued reform in prescribing practices, pain management alternatives, and addiction treatment access.

Figure 3.11 Opioid Epidemic

Legal and governmental actions against pharmaceutical companies in connection with the opioid epidemic began gaining momentum in the early 2000s and have intensified over the past decade. Investigations revealed that several companies failed to comply with federal regulations, including neglecting to monitor and report suspicious orders of opioid medications. Both brand-name manufacturers, such as Purdue Pharma (maker of OxyContin), and generic producers were implicated, with generic manufacturers often facing less scrutiny in the early stages of the crisis [36]

These companies generated billions in profits while contributing to widespread addiction and overdose deaths. In response, the federal government, numerous states, Native American tribes, and local municipalities launched lawsuits targeting deceptive marketing practices, fraud, and lax oversight. These legal actions focus not only on individual harm but also on systemic failures that exacerbated the public health crisis. Allegations include oversaturation of the market, misleading claims about addiction risk, and failure to implement safeguards against misuse [37]

Recent settlements—some reaching into the billions—have begun to fund opioid recovery programs, treatment services, and public health initiatives. While these outcomes offer some accountability, experts argue that broader reforms in pharmaceutical regulation and corporate accountability are still needed to prevent future public health disasters.

The ripple effects on families and communities are difficult to quantify. While overdoses and deaths can be counted, loss and grief is immeasurable. Diminished parenting, loss of employment, loss of housing, and broken relationships affect families, friends and work places. The effects of drug addiction and trauma are generational; we will not know how many families have been affected by this epidemic that has crossed centuries until well into the future.

Keeping our Families Healthy

If you were to spend a few minutes brainstorming a list, what would you include as the most important requirements to keeping your family healthy? While this chapter has focused on health care and health insurance as important aspects of health management, these authors would like to emphasize that health care starts with access and decision-making related to exercise, diet, relationships, work, sleep, intellectual stimulation, addictive substances, education, and social life. This is our list; perhaps you have other aspects to add!

Importantly, those individual and family decisions are directly impacted by the social institutions and processes at the core of the United States. Past and present laws, policies, practices, and biases that create and reinforce inequities mean that families live with vastly different access to resources including food, safe and stimulating outdoor environments, time, work environments, social life, and health care.

For example, many families live without easy access to recreational trails and playgrounds. The Housing Now chapter of this text details the ways in which laws, regulations, and lending corporations have actively participated in pushing minoritized racial-ethnic groups into these areas. We must pay attention to these past practices and the ways that they impact present families’ health. During the current (2020) COVID-19 Pandemic it is becoming clear that the virus is transmitted more easily in crowded spaces indoors than in the outdoors. There is a disproportionate number of coronavirus cases and deaths amongst minoritized populations in the United States[38] and it is possible that lack of access to outdoor spaces plays a role. So at the same time that this lack of resources makes it more difficult to maintain everyday physical and mental health, it may also contribute to illness, hospitalization, loss of employment, and even death during the pandemic.

This video from the American Medical Association features an interview with Doctor Aletha Maybank and explains how funding, data collection and the overlap with structural discrimination affect the rates of the virus.

Institutionalized inequities have been amplified during the pandemic. Crowded work environments such as meat-packing facilities; food deserts; less health insurance, less access to health care and virus testing as measured by geography and transportation options; and greater likelihood to experience discrimination, stress, and lack of sleep, are some of the factors that contribute to greater numbers of Black, Native, and Latinx families being affected by the COVID-10 virus.[39] These overlapping factors are discussed throughout this text.

It is important to recognize the role of activism in alleviating all social problems, including the problem experienced by so many families in the United States: poor health that could be improved by adequate health care. There is hope; there are many countries that have differing successful models of health care that give all citizens access. In this country there are multiple groups, many led by physicians or other medical professionals, that are working to create and/or modify systems so that all individuals and families can access the basic health care that they need. Two organizations that are prominent are Health Care for ALL Oregon and Physicians for a National Health Program.

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 25 identifies health as a human right.

Article 25.

(1) Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

(2) Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.[40]

Some non-industrialized nations and all industrialized nations, with the United States as the notable exception, have adopted some form of universal health-care system since the 1948 adoption of this Declaration. The irony is that the framework for the human rights declaration came from the United States and the work of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his wife and Statesperson Eleanor Roosevelt.[41] The United States does not have an actual health care system, but rather multiple systems of health insurance accessed: via employment, via family configuration as defined by government structures, state-funded block programs, and federal programs for specific groups such as people who are indigent, disabled, or older. In other words, not all families.

While families in the United States strive to make the best choices for themselves, they are limited by the existing access to resources needed to be as healthy as possible. Some of these inequities were created by past laws and practices. But those, and others, can be adjusted and changed. The societal and governmental commitment to the standards of health and well-being as identified in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights is a way to begin.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Health Care and Health Insurance: A Comparison” is adapted from “Global Aspects of Health and Health Care” in Social Problems by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptation: edited for clarity and accuracy.

Figure 3.6. “Coverage Gap for Adults. Based on data from Statistical Abstracts/U.S. Census.

Figure 3.7. “Chicago, 2012” by gregorywass. License: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 3.9. “Money Behind Health Care” by Truthout. License: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 3.10. “Retail RX spending per capita each year” by The Conversation. License: CC BY-ND 4.0. Based on data from The Commonwealth Fund.

Figure 3.11. “The Opioid Epidemic by the Numbers” by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Public domain.

Figure 3.13. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” by the United Nations. License: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Income, Poverty and Health Insurance – Health Insurance Presentation” by US Census Bureau. Public domain.

Open Content, Original

Figure 3.8. Image by Katie Niemeyer. License: CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.12. “COVID-19: Physical Distancing in Public Parks and Trails” (c) National Recreation and Park Association. Image used with permission.

“COVID-19 Update for April 21, 2020” (c) American Medical Association. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

- Russell, J. W. (2018). Double standard: Social policy in Europe and the United States (Fourth edition). Rowman & Littlefield. ↵

- Reid, T. R. (2010). The healing of America: A global quest for better, cheaper, and fairer health care. Penguin Books. ↵

- Murad, Y. (2019, February 20). CMS estimates annual U.S. health care spending to hit $5.96 trillion by 2027. Morning Consult. ↵

- The Global Statistics. (2024, May 15). Health insurance coverage in the U.S. 2025 | Stats & facts ↵

- Rosen, A. (2025, July 30). The changes coming to the ACA, Medicaid, and Medicare. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2024, May 6). Nondiscrimination in health programs and activities: Final rule. Federal Register, 89(88), 37522–37660. ↵

- Martinez, L., Smith, G. R., & Jule, C. (2024, May 16). Final rule released for Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act. National Law Review. ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2024, May 6). Nondiscrimination in health programs and activities: Final rule. Federal Register, 89(88), 37522–37660. ↵

- Martinez, L., Smith, G. R., & Jule, C. (2024, May 16). Final rule released for Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act. National Law Review. ↵

- Diana, A., Tolbert, J., & Mudumala, A. (2024, October 29). Medicaid and CHIP eligibility expansions and coverage changes for children since the start of the pandemic. KFF. ↵

- Diana, A., Tolbert, J., & Mudumala, A. (2024, October 29). Medicaid and CHIP eligibility expansions and coverage changes for children since the start of the pandemic. KFF. ↵

- Brooks, T., Tolbert, J., Mudumala, A., Diana, A., Gardner, A., Osorio, A., & Preuss, S. (2025, April 1). Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies as states resume routine operations following the unwinding of the pandemic-era continuous enrollment provision. KFF. ↵

- Ochieng, N., Cubanski, J., & Neuman, T. (2024, September 23). A snapshot of sources of coverage among Medicare beneficiaries. KFF. ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2025). Medicare Advantage/Part D contract and enrollment data. CMS.gov. ↵

- Cubanski, J., & Damico, A. (2025, July 16). Key facts about Medicare Part D enrollment, premiums, and cost sharing in 2025. ↵

- Ochieng, N., Cubanski, J., & Neuman, T. (2024, September 23). A snapshot of sources of coverage among Medicare beneficiaries. KFF. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2024, September). Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2023. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2023, November). Uninsured rates by gender and county: 2022. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2024, September). Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2023. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2023, November). Uninsured rates by gender and county: 2022. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2024, September). Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2023. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2024, September). Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2023. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2023, November). Uninsured rates by gender and county: 2022. ↵

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2023, August). Disparities in healthcare access among nonelderly adults: Findings from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. ↵

- Halpern, M. T., Ward, E. M., Pavluck, A. L., Schrag, N. M., Bian, J., & Chen, A. Y. (2008). Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: A retrospective analysis. The Lancet Oncology, 9(3), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70032-9. ↵

- Wilper, A. P., Woolhandler, S., Lasser, K. E., McCormick, D., Bor, D. H., & Himmelstein, D. U. (2009). Health insurance and mortality in US adults. American Journal of Public Health, 99(12), 2289–2295. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.157685. ↵

- Wouters, O. J., McKee, M., & Luyten, J. (2020). Estimated research and development investment needed to bring a new medicine to market, 2009–2018. JAMA, 323(9), 844–853. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1166. ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (2023). NIH research funding supports early-stage drug discovery. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-research-funding-supports-early-stage-drug-discovery. ↵

- Wouters, O. J., McKee, M., & Luyten, J. (2020). Estimated research and development investment needed to bring a new medicine to market, 2009–2018. JAMA, 323(9), 844–853. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1166. ↵

- Congressional Research Service. (2023, December 8). Medicare drug price negotiation under the Inflation Reduction Act: Industry responses and potential effects (CRS Report No. R47872). https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47872. ↵

- Haeder, S. F. (2019, February 7). Why the US has higher drug prices than other countries. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-the-us-has-higher-drug-prices-than-other-countries-111256 ↵

- Kang, S.-Y., DiStefano, M. J., Socal, M. P., & Anderson, G. F. (2019). Using external reference pricing in Medicare Part D to reduce drug price differentials with other countries. Health Affairs, 38(5), 804–811. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05207. ↵

- Hickey, K. J., Rogers, H.-A., & Wreschnig, L. A. (2023, December 8). Medicare drug price negotiation under the Inflation Reduction Act: Industry responses and potential effects (CRS Report No. R47872). Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47872 ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023, October). The opioid crisis: Understanding the epidemic and federal response. ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023, October). The opioid crisis: Understanding the epidemic and federal response. ↵

- Haffajee, R. L., & Mello, M. M. (2017). Drug companies’ liability for the opioid epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(24), 2301–2305. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1710756. ↵

- Haffajee, R. L., & Mello, M. M. (2017). Drug companies’ liability for the opioid epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(24), 2301–2305. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1710756. ↵

- Godoy, M. and Wood, D. (2020, May 30). Growing data show Black And Latino Americans bear the brunt. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/05/30/865413079/what-do-coronavirus-racial-disparities-look-like-state-by-state ↵

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, June 25). COVID-19 in racial and ethnic minority groups. Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html ↵

- United Nations. (1948, December 10). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ ↵

- Gerisch, M. (n.d.). Health care as a human right. Human Rights Magazine, 43(3). Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/the-state-of-healthcare-in-the-united-states/health-care-as-a-human-right/ ↵

Unfair access or treatment, usually systemic in nature.