15 Housing Now!

Elizabeth B. Pearce; Katherine Hemlock; Carla Medel; and Joyce Baptist

Housing is another word for the place that families go each night to find shelter not only from the physical elements, but also to find enough emotional safety that they can become centered, rejuvenated, and sleep securely. In the best scenarios it provides not only security, but a place for families to love and nurture the self and one another.

Cardi B, a famous rapper (born as Belcalis Almanzar), describes being able to move out of her abusive boyfriend’s home with money earned from her work stripping in a club. “There were two pit bulls in that house, and I had asthma. There were bed bugs, too,” she told Vibe. “On top of that, I felt like my ex-boyfriend was cheating on me, but it was like even if he was cheating on me, I still can’t leave because—where was I gonna go?”[1]

In Cardi B’s case, she had safety from the outside physical world. But she was not safe inside her home. This is just one example of the complexities of housing, and specifically the ways that inequities play out in the United States.

Income is the primary determining factor in housing access. Price, availability, location, and macroeconomics all play a role, but a family’s annual income is the main determinant in housing affordability.[2] Therefore, inequities in income distribution directly affect housing access, and the capability of families to be safe, secure, and able to function to their maximum potential.

Cardi B grew up living between two different Bronx neighborhoods in New York City. When she describes her parents, she says, “I have real good parents, they poor. They have regular, poor jobs and what not,” she said in an interview with Global Grind. “They real good people and what not, I was just raised in a bad society”[3]. It is common in the U.S. for families to have multiple wage-earners, with multiple jobs, and still be unable to afford adequate housing.

Part-time and temporary jobs frequently come with lower pay and fewer benefits such as health care, sick leave, and other paid and unpaid leaves. This makes it harder to budget for regular expenses such as food and housing. These jobs are unequally distributed by sex, immigration status, and ethnic groups. Affordable housing is defined as housing that can be accessed and maintained while paying for and meeting other basic needs such as food, transportation, access to work and school, clothing, and health care. Diverse income levels, reinforced by governmental and lending practices that discriminate based on racial-ethnic groups, immigration status, and socioeconomic status, widen the gap between those who are housing secure, housing insecure, and homeless.

Homelessness

As of January 2024, homelessness in the United States reached a record high, with 771,480 individuals experiencing homelessness on a single night—an 18% increase from the previous year. This surge is attributed to the affordable housing crisis, inflation, stagnating wages, and the expiration of pandemic-era support programs [4] Families with children were particularly affected, with homelessness among this group rising by 39%, totaling 259,473 people. Nearly 150,000 children under the age of 18 were homeless on a single night in 2024, marking a 33% increase from 2023 [5] . Additionally, over 1 million public school students were identified as homeless during the 2021–2022 school year, representing 2.2% of all students nationwide [6] These students face significant educational barriers, including chronic absenteeism and lower graduation rates.

Unaccompanied youth also represent a substantial portion of the homeless population. In 2025, an estimated 700,000 youth were experiencing homelessness without a parent or guardian, with approximately 34,120 of them under age 25 living unsheltered [7] Youth aged 18 to 24 comprise about 8% of the total homeless population. Demographic disparities remain stark: youth of color are 83% more likely to experience homelessness than their white peers, and LGBTQ+ youth face a 120% higher risk, often following family rejection [8] Black Americans are also disproportionately affected, comprising 32% of the homeless population despite representing only 12% of the U.S. population [9]

Homelessness and College Students

Figure 9.3 Statistics on college students facing housing insecurity

Homelessness among college students in the United States is a growing and deeply concerning issue. According to the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:20), approximately 8% of undergraduate students and 5% of graduate students reported experiencing homelessness during the 2019–2020 academic year, translating to over 1.5 million students nationwide [10] These students often lack stable housing and may live in shelters, cars, hotels, or temporarily with friends or family. The rates of homelessness are similar across two-year and four-year institutions, with 14% of students at both types of colleges reporting homelessness [11] Additionally, housing insecurity—a condition where students face unstable or unaffordable living situations—affects 52% of students at two-year colleges and 43% at four-year institutions.

The issue disproportionately affects marginalized groups, including students of color, LGBTQ+ students, parenting students, and those with disabilities [12] Many homeless college students are not visibly unsheltered but instead engage in “couch surfing” or live in temporary accommodations, making them harder to identify and support. The lack of affordable housing near campuses, insufficient financial aid, and limited access to support services contribute to this crisis. Addressing student homelessness requires coordinated efforts across higher education, housing policy, and social services to ensure that all students have access to safe, stable housing while pursuing their education.

Forms of Homelessness

Living in tents, couch surfing, and sleeping in cars are all recognized forms of homelessness. In response to rising housing costs and limited shelter capacity, formal encampments known as “tent cities” have emerged across the United States. These encampments offer a semblance of stability and community for people experiencing homelessness, though most remain unsanctioned and vulnerable to eviction. One notable exception is Dignity Village in Portland, Oregon—a city-sanctioned, self-governed community founded over 20 years ago. Residents pay a modest monthly fee, contribute work hours, and abide by community rules, creating a rare model of autonomy and stability for unhoused individuals. [13]

Despite their role in providing temporary shelter, tent cities are increasingly under legal threat. As of 2023, more than 100 jurisdictions across the U.S. have enacted laws banning camping in public spaces, making it illegal to live in tents or vehicles. [14] These policies often result in forced evictions or “sweeps,” displacing residents and exacerbating the instability they already face. The number of tent cities has surged in recent years, with a 1,342% increase in reported encampments between 2007 and 2017. By mid-2017, 255 encampments were documented, with 75% deemed illegal, 20% silently sanctioned, and only 4% officially legal. [15]

Tent cities have become a visible response to the shortage of shelter beds and the lack of affordable housing. While some cities have begun experimenting with sanctioned encampments, many continue to criminalize unsheltered homelessness, leaving thousands of people with few safe options. The debate continues over whether tent cities should be treated as temporary solutions or integrated into broader housing strategies.

The socially constructed ideas of “normal” or “acceptable” identities are barriers to many people in accessing shelter, housing and other services. In homeless shelters transgender women may be refused admittance by the women’s shelter and at risk of violence at the men’s shelter. More progress must be made to provide security for all, regardless of identity.[16]

Another barrier some women with children face in seeking shelter from domestic violence is the shelter rules themselves. Early curfews and overly strict rules can compromise the empowerment of residents. Many women fleeing domestic violence find themselves facing punitive and inflexible environments that mimic the patterns of control they are trying to escape. The Washington State coalition against domestic violence called Building Dignity “explores design strategies for domestic violence emergency housing. Thoughtful design dignifies survivors by meeting their needs for self-determination, security and connection. The idea here is to reflect a commitment to creating welcoming accessible environments that help to empower survivors and their children.”[17]

Housing Insecurity

Housing insecurity is less transparent than homelessness. People who are homeless are somewhat visible, but we may be less likely to know whether or not someone is housing insecure. That’s because it is an umbrella term that encompasses many characteristics and conditions. Signs of housing insecurity include missing a rent or utility payment, having a place to live but not having certainty about meeting basic needs, experiencing formal or informal evictions, foreclosures, couch surfing, and frequent moves.[18] It can also include being exposed to health and safety risks such as mold, vermin, and lead, overcrowding, and personal safety fears such as abuse.[19] Cardi B’s living situation, which she describes as “practically homeless,” illustrates housing insecurity.

Housing insecurity remains a pressing social issue in the United States, affecting a significant portion of the population. As of 2023, approximately 32.8% of all U.S. households—or 41.8 million households—were considered cost-burdened, meaning they spent more than 30% of their income on housing

Somewhere In-Between

A well-established housing system that is often left out of the ‘standard’ talks regarding housing is immigrant housing. There are many immigrants who come to the United States as part of a guestworker program, which dates back to 1942 with the Bracero Program and continues through the hiring today of H2-A workers. Although these folks are called “guest workers,” they are not treated in the way that we imagine treating honored guests when it comes to living spaces.

The protections provided to these guest workers vary depending on the program they are under, so the quality of living varies widely but is often low quality. The housing vicinities lack basic necessities and are often in areas considered to be dangerous. Many guest workers find themselves living in one-room containers that later may be split up between many workers. Other guest workers find themselves living in what are called ‘Tent Cities,’ placed right next to the field where they are picking crops. One tent is provided to fit multiple guest workers or an entire family.

These living spaces are often in very rural locations, which isolate these workers and make them totally reliant on their employers. Many employers forbid them from bringing visitors, which reinforces the guest workers’ dependence on the employer and limits the likelihood of reports about the poor living conditions or other violations.[23]

The Influence of Institutions:

Governments and Lending Institutions

Federal, state, and local governments all influence housing access via laws, zoning rules, permitting processes, and regulations. In addition, the government has the power to regulate the way that most Americans access home ownership, which is a loan agreement between an individual or couple and a lending institution such as a bank or credit union. In fact, it is the lending institution who owns any home, until the individual or couple completely pays the mortgage, which is a combination of the home’s original price and the interest that is charged, typically over a 15-, 20-, or 30-year loan.

Together, government and lending institutions control who can borrow money, where they can access housing, the down payment required, and the interest rate that each family pays. These regulations do not treat all families equally: socioeconomic status, racial-ethnic identity, marriage and sexuality, and immigrant and documentation status have all played a role in lending policies over time in the United States. Immigrants and individuals with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status have difficulty securing loans due to ambiguous federal legislation affecting their status. People who do not have a social security number are eligible for loans, but these typically require a higher down payment and higher interest rates.

Home foreclosures added to the economic disparity following the housing market crash of 2008. Over half of US States were affected by prior predatory lending practices and lack of oversight of the banking system. Uninsured, private market subprime loans were made available with looser requirements, quickly driving up the price of homes so that some people owed more on their house than it was worth. Many were considered “underwater in their loans” or “upside-down” in their home value and defaulted on payments. Banks took back homes and many families were forced into shelters, into living in their cars, or into the homes of family members increasing the numbers of cost-burdened, housing insecure, and homeless families.

Where Families Live

Considering the location of families in the United States, we will briefly look at three factors: geography; household size; and types of locations, which commonly include urban, suburban, and rural communities. Exurbs, a relatively new term, describes areas just outside of suburban communities which typically feature low density housing and large homes. These may overlap into farm or forested areas, but are not considered rural.

Geography

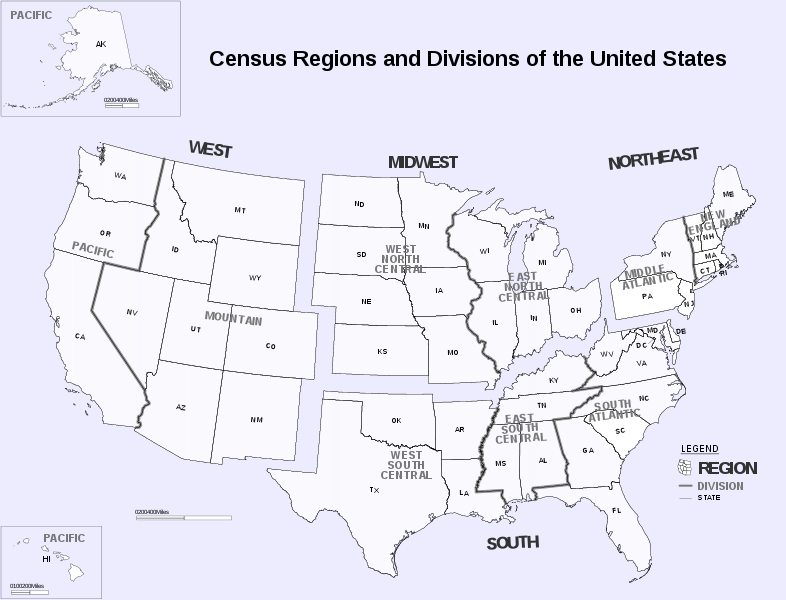

Population distribution is divided into four main regions by the U.S. Census Bureau in order to register the population: the Northeast, Midwest, South, and West; see the map below for divisions within regions.

Population distribution across the United States remains uneven, with the highest densities concentrated in the Northeast and Southern regions, followed by notable clusters in the East North Central division of the Midwest and the Pacific division of the West, which includes Oregon

Communities

Where families live can also be examined related to living in urban, suburban, rural, and exurban areas. Over the second half of the 20th century and the first part of the 21st century, families generally moved away from urban centers and into the suburbs. But the recession of 2008-2015 reversed that trend and urban areas made some growth, while suburbs and exurbs declined. Since 2016, the overall trend has again shifted, increasing family growth in suburbs and metropolitan areas (as opposed to urban cores), with Midwestern metro areas seeing the most growth.[28] To understand the demographics of who lives in which kind of community, read this article from the Pew Research Center: What Unites and Divides Urban, Suburban and Rural Communities. Values, racial-ethnic groups, and education are all factors in family location.

Environments and locations have differing health advantages and risks. Air quality, access to green spaces, clean water, and places to recreate are often described as “quality of life” factors. But a greater emphasis is critical as these are considered to be as important to overall health as are genetics and lifestyle.[29] Air and water will be discussed more in depth in the Food, Water, and Air chapter of this text. With the advent of shelter-at-home restrictions related to the pandemic of COVID-19, home environments have become even greater a factor in our overall health. For more on how to assess your environment and its importance to health, watch this TEDMED TALK with Bill Davenhall.

Household Size

The average household size in the United States has shown a modest increase in recent years, reversing a centuries-long decline. From an average of 5.79 people per household in 1790, the number dropped to 2.58 in 2010, but has since risen slightly to 2.55 in 2024. [30] This shift is influenced by several factors, including economic pressures that have led families to “double up” in shared housing arrangements. The lingering effects of the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic have made independent living less attainable for many, especially young adults. In fact, more than half of Gen Z adults aged 18 to 24 now live with their parents, citing high rent, inflation, and student debt as key reasons . [31]

Another contributor to the rise in household size is the growth of multigenerational households, which now account for 18% of the U.S. population [32]. These arrangements are particularly common among Asian (24%), Black (26%), and Hispanic (26%) families, compared to 13% of non-Hispanic White families. Economic and cultural factors both play a role, with multigenerational living offering financial stability and caregiving support. Additionally, economic expansions and downturns have a direct impact on household composition. Research shows that unemployment and inflation reduce real household income, prompting more individuals to consolidate living arrangements for financial survival [33].

This trend toward larger households has implications for housing demand and the broader economy. While it may reduce the need for new housing units, it also affects consumer behavior—such as spending on utilities, furnishings, and digital services. If the trend continues, it could reshape housing policy and urban planning in the years ahead.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 9.1. “Cardi B live auf dem Openair Frauenfeld 2019″ by License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.2. “home sweet home” by Libor Gabrhel. License: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 9.4. “Statistics on college students facing housing insecurity.” Source: 2021 #RealCollege Report

Figure 9.5. Photo by Pxfuel. License: Pxfuel terms of use.

Figure 9.6. “Census Regions and Division of the United States” by US Census Bureau. Public domain.

Figure 9.7. “2010 Population Distribution in the United States and Puerto Rico” by US Census Bureau. Public domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.3. “Comparison of Basic Needs Insecurity Rates” (c) The Hope Center. Used with permission.

- Akhtar, A. (2017, September 27). How Cardi B escaped poverty to become the first female rapper in 19 years to top the charts. http://money.com/how-cardi-b-escaped-poverty-to-become-the-first-female-rapper-in-19-years-to-top-the-charts/ ↵

- Tilly, C. (2006). The economic environment of housing: Income inequality and insecurity. In R. G. Bratt, M. E. Stone, and C. Hartman, A right to housing: Foundation for a new social agenda (pp. 20-35). Temple University Press. ↵

- Shamsian, J. & Singh, O. (2019, October 10). How Cardi B went from a stripper to a chart-topping rapper. Business Insider. https://www.insider.com/who-is-cardi-b-bodak-yellow-2017-9 ↵

- (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD], 2024). The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress: Part 1 – Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. ↵

- (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD], 2024). The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress: Part 1 – Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. ↵

- (National Center for Homeless Education [NCHE], 2023). Student homelessness in America: School years 2019–20 to 2021–22. https://nche.ed.gov/data-and-stats/. ↵

- (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2025). 2025 homelessness data dashboards. https://endhomelessness.org/resources/toolkits-and-training-materials/2025-homelessness-data-dashboards/. ↵

- Covenant House. (n.d.). Young people of color facing homelessness. Retrieved from https://www.covenanthouse.org/homeless-issues/people-of-color. ↵

- (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD], 2024). The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress: Part 1 – Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2025, May 7). Hungry for knowledge: Food insecurity and how it affects college students. https://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/psychology-teacher-network/introductory-psychology/food-insecurity. ↵

- Bipartisan Policy Center. (2023, August 15). Housing insecurity and homelessness among college students. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/housing-insecurity-and-homelessness-among-college-students/. ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2025, May 7). Hungry for knowledge: Food insecurity and how it affects college students. https://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/psychology-teacher-network/introductory-psychology/food-insecurity. ↵

- Next City. (2023, October 17). In Portland’s self-governed Dignity Village, the unhoused make their own rules. https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/portland-dignity-village-homeless-self-governed. ↵

- USA Today. (2023, November 2). Homeless in the US: Tent cities banned as more people lose their homes. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2023/11/02/homeless-tent-cities-banned/71839200007/. ↵

- Invisible People. (n.d.). Tent cities in America. https://invisiblepeople.tv/tent-cities-in-america/. ↵

- National Center for Transgender Equality. (2019, June 9). The Equality Act: What transgender people need to know. https://transequality.org/blog/the-equality-act-what-transgender-people-need-to-know ↵

- Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.). Building dignity: Design strategies for domestic violence shelter. https://buildingdignity.wscadv.org/ ↵

- Office of Policy Development and Research. US Department of Housing and Urban Development. (n.d.). Measuring housing insecurity in the American housing survey. PD&R Edge Magazine. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-frm-asst-sec-111918.html ↵

- Health People 2020. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Housing instability. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/housing-instability ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Resolution on ending homelessness. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/resolution-ending-homelessness.pdf ↵

- National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. (2018). Tent City, USA: The growth of America’s homeless encampments and how communities are responding. https://www.homelesslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Tent_City_USA_2017.pdf. ↵

- Sullivan, L. (2012). Tent cities in America: A report on homeless encampments in the United States. Journal of Housing and Community Development, 69(3), 22–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23018618. ↵

- Southern Poverty Law Center. (n.d.). Guest worker rights. Retrieved February 20, 2020, from https://www.splcenter.org/issues/immigrant-justice/guest-workers ↵

- United States Census Bureau. (2024, December 21). State population totals and components of change: 2020–2024. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html. ↵

- United States Census Bureau. (2024, December 21). Annual estimates of the resident population for the United States, regions, states, and Puerto Rico. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2024/popest-nation.html. ↵

- Portland State University Population Research Center. (2024, November 15). Preliminary Oregon population estimates. https://www.pdx.edu/population-research/population-estimates. ↵

- World Population Review. (2024). US states by population growth rate. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/state-population-growth-rate. ↵

- Frey, W. H. (2018, March 26). US population disperses to suburbs, exurbs, rural areas, and “middle of the country” metroes. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/03/26/us-population-disperses-to-suburbs-exurbs-rural-areas-and-middle-of-the-country-metros/ ↵

- Office of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2019, May 14). Healthy homes reports and publications. Retrieved May 14, 2020, from https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/healthy-homes/index.html ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2024, December 19). Vintage 2024 national and state population estimates. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2024/national-state-population-estimates.html. ↵

- Population Research Center, Portland State University. (2024, November 18). Oregon migration population data update. Common Sense Institute. https://www.commonsenseinstituteus.org/oregon/research/housing-and-our-community/population-data-update. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2024, December 19). Population change by region. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2024/comm/population-change-by-region.html. ↵

- Ball, L., Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. (2025, June). The ups and downs of household income. https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/el2025-06.pdf ↵

Unfair access or treatment, usually systemic in nature.

Housing that can be accessed and maintained while paying for and meeting other basic needs such as food, transportation, access to work and school, clothing, and health care