1 Literacy Essentials

Section 1: Literacy Essentials

Welcome to the world of literacy! However, literacy is hardly something new in your life. Literacy has become an essential part of all of our lives. This text is designed to help you along your journey to be confident in teaching literacy skills that complement the teaching of your content area.

We start with the focus of the entire course–getting your students to read. The following video shares some students’ ideas on why they read.

But, first, we must determine just how we define literacy and what types of literacy and texts students will experience in your classroom.

The days of the traditional role of reading have been overtaken by a 21st Century version that involves a wide array of skills and “texts.” We are going to examine how we define literacy today and the theory and research that support approaches to helping students acquire the necessary skills to meet their literacy needs in the classroom and beyond.

Think for a minute–did you read anything today? Did you grab a favorite book, slouch into a comfortable chair and read? OK, maybe you didn’t do that, but did you…read an article on the Internet? Read a stoplight on your way to class? Or maybe you read the ingredients on the label of your morning beverage or breakfast bar? Or maybe you just continually “read” the clock to see when a class would be over?

It’s amazing when you think of all the times you use your literacy skills–almost automatically, in some instances–through the day.

So, as part of our challenge, we need to convince our students (some more than others) that literacy is an important element of their lives…and for their future.

If we truly want our students to learn our content–and to succeed beyond our classrooms, then we need to help them understand that improving their literacy skills is essential.

Section 2: Defining Literacy

In the 1960s, the term was simply “reading.”

Elementary students were divided into ability-leveled groups with clever names such as Bluebirds and Cardinals–which teachers (somewhat erroneously) believed masked the fact that the Cardinals were the superior readers, while the Bluebirds were all students who struggled to read.

They spent time reading aloud from their Dick and Jane textbooks, having the teacher correct their errors, and then repeating it correctly to show that they were “learning to read.”

Today, we have moved beyond a simplistic definition of reading. Like so many developments in education during the past few years, “it’s complicated.”

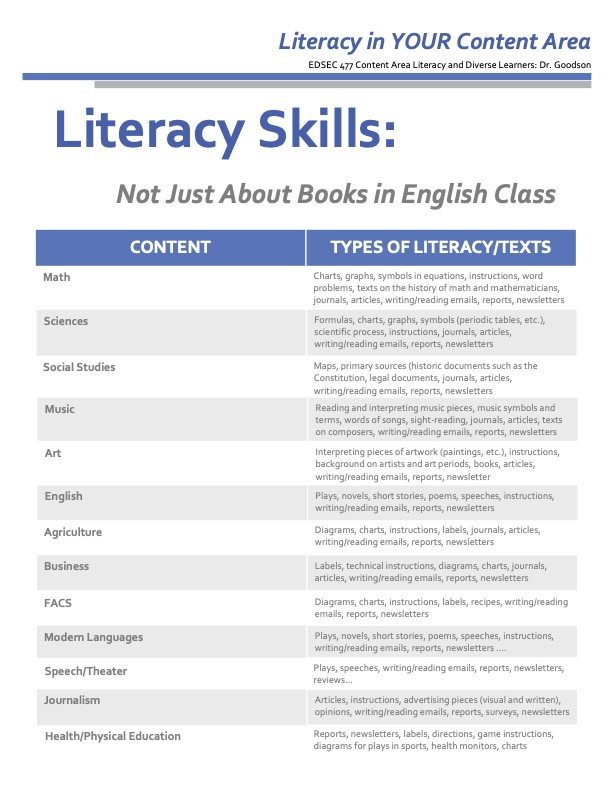

We now have established a much broader view of literacy. Instead of seeing reading as a skill used solely to decipher a chapter in a traditional textbook, we are opening it up to a wide, all-encompassing collection of “texts.” And, thanks in part to technology, the list keeps growing. Consider these possibilities:

- Music scores

- Mathematical equations

- Scientific formulas

- Historic documents such as the Declaration of Independence

- Favorite cookie recipes

- Maps

- Nutrition labels

- Livestock feed bags

- Graphs

- Blueprints

- Menu

- Press releases

- Blogs

- Lab directions or reports

The list, as you can tell, could go on and on. We “read” every day–sometimes for entertainment, sometimes for safety, sometimes for instructions, sometimes for awareness.

Every day we read street signs, text messages, blogs on the Internet, instructions, and so much more. All of these require our ability to see images, symbols, or letters, and interpret them (sometimes while we’re driving 75 miles an hour (or faster?) on an Interstate highway as we zip by a road sign to determine meaning.

When you consider the quantity of opportunities for us to “read” each day, it becomes apparent just how impactful our literacy skills can be to our lives.

Definitions

First, let’s examine the definition of literacy. Check out: NCTE Literacy Definition

Now read the United National Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s definition here: UNESCO

Does one definition make more sense than the others? Does one seem to connect more with your own content area?

Likewise, each content area has its own specific literacy needs. We’ll address those in more detail later in this chapter.

Section 3: Good Readers

It is important that we know what abilities and attitudes good readers seem to have in common–so we can help those who struggle learn to be successful.

You’ve probably heard it said–about yourself or a classmate: “He’s just such a good reader; he reads book after book.” Or…the opposite, “She’s never been a good reader–she hates books and just struggles all the time.”

So what is a good reader?

First, let’s think of your own reading experiences.

- What do you remember as your “first” book as a child? How many times did you read it/have it read to you?

- As you entered elementary school, what kind of reading did you do? Were you placed in a reading book? If so, why?

- Moving into middle school, what kind of reader were you?

- And high school? Did you enjoy reading? Did you become a better reader? Why or why not?

- What influenced you to become the kind/level of reader you are today? Who’s to blame–or who gets credit?

In the preceding video clip, Cris Tovani, a nationally recognized middle-school teacher, discusses how good readers approach a book. Tovani, who has written several books on reading and presents nationally on the subject, is talking to her reader workshop class about some of the approaches good readers use when tackling a text. Tovani provides teacher-friendly approaches to helping get students engaged in reading.

As a reader, did you:

- Fake a teacher out so he or she would think you were reading?

- Effectively draw conclusions for what you were reading?

- Or take everything you read literally?

- What “signals” did you use to recognize you were “stuck” in the text?

- How did you try to get “unstuck”? What did you do? Were you successful? Or…did you simply get frustrated and stop reading?

- How will you help your own students when they experience similar problems while reading a text in your classroom?

Section 4: Research–The Deep End of the Pool

Theoretical Framework and Key Research

Many years ago as a teenager, I babysat to earn extra money–upon reflection of my success at that job, it possibly served as a guiding experience for choosing secondary education instead of elementary.

Career choices, aside, not so many years ago, I ran into one of the children I had babysat–only she was now grown up and a mother of two. She reminded me of two things: 1) how old I had become and 2) my babysitting days and how I’d once tried to teach her to read.

“You just said the words louder and louder,” she said with a laugh. And that, at age 13, was my approach to teaching reading: Shout the words to the “student” until the student “gets it.”

Not so successful.

I have changed my approach quite a bit over the past years, mostly because I’ve done my own reading–of the research. That allows me to make better decisions for teaching students.

Once we understand the importance of literacy to our content area, we need to know some of the theory behind it. It’s important that we know the possibilities and the research behind them to support the decisions we make–regarding literacy as well as all those other decisions we make each and every day. So, let’s look at some of the background research that has formed the framework for literacy education.

An article by Alexander and Fox (International Reading Association, 2004), “A Historical Perspective on Research and Practice,” provides an extensive look at the education profession’s journey toward teaching reading and other literacy skills.

Let’s read some of that to get a clearer idea of our approaches:

The authors give details of a half century of reading research. It’s important to see where we’ve been regarding literacy education–from our beginnings (in my case, my “shouting” approach) through today’s emphasis on student engagement.

In the classrooms you’ve visited for your various field experiences and other opportunities, have you seen:

- A focus on engagement?

- Pieces of approaches from previous eras in learning?

- What has been the most effective?

- And, possibly most important, where do we go from here?

The National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) provides a policy research brief on the topic of adolescent literacy. Read it here, especially research-based recommendations for teachers on page 6: Adolescent Literacy Research Brief.

The brief lists several qualities that teachers need to help students achieve.

- Of those listed, what are your strengths as an educator?

- What areas do you need to work on to help meet your students’ literacy needs?

Meanwhile, here is a link to the International Literacy Association, formerly the International Reading Association, where the organization provides its position statement on adolescent literacy: ILA Position Statement.

The following is a TEDx Talk on literate life, by Professor Seth Lerer, Dean of Arts and Humanities and Distinguished Professor at the University of California at San Diego. With humor, he discusses language–from early days of books to today’s emails.

Section 5: Disciplinary Literacy

In most educational systems, students move from the general to the more specific; they are in general classes during their elementary years, then take more specifically focused courses as they move into middle and high school. They choose, for lack of a better term, a track–the Advanced Placement courses, the standard classes, and electives that often are more targeted toward their interests.

As we examine literacy in schools, we see a similar movement toward specialization. In students’ early school years, the focus in their literacy work is usually fairly general–as students begin building the base of their vocabulary and understanding. At the secondary level, however, their more advanced classes in specific content areas require a more specific approach to the language and literacy.

Consider, for example, the reading you would do in a math class vs. a literature class. While the vocabulary may not be more difficult in one class over the other, we “read” differently in each of the classes.

In math, we’re making sense of terms such as obtuse, dimension, and congruent. In a literature class, we’re focusing on terms such as foreshadowing, rhyme, and, a personal favorite, onomatopoeia. Teachers and students alike have to approach this specific disciplinary literacy in a unique way. In the following video, ideas are shared on the importance of disciplinary literacy in your own classroom.