Introduction

What Is English 200: Expository Writing II?

English 200 (“Expository Writing II”) will introduce you to persuasive writing. Often when we think about persuasion, we think about winning an argument. Yet, as you’ll see in this textbook, theories and practices of persuasion are much broader than that. In fact, throughout the semester you’ll work to think of persuasion in terms of moving a reader in a number of different ways: helping a reader more fully understand a complex issue, making it easier for a reader to better hear you and your perspective, encouraging a reader to consider a different viewpoint, and asking a reader to take a particular action. You will also learn how to analyze and build different kinds of arguments, using some of the most useful and common tools of the trade, including rhetorical appeals, the Toulmin model, and Rogerian communication. Throughout all of these processes, we’ll ask you to pay particular attention to your audience, continually keeping an audience’s values, beliefs, and needs in mind.

Indeed, if there is a key phrase in English 200, it is “audience-based reasoning.” Focusing on your readers will allow you to make decisions about what evidence to choose, what organizational patterns to employ, and what tone and style to use. Importantly, this course enhances your ability to imagine the needs and values of your readers and to understand the reasons for why they might hold differing viewpoints. In doing so, you will also be asked to consider the sources of your own knowledge, examining your own values, beliefs, and needs to determine how to best build bridges between you and your readers. This will require what rhetorical theorist Krista Ratcliffe calls “rhetorical listening.” Instead of simply listening to other perspectives to find a way to respond, or even to understand the content of what someone is saying—although both of those are important skills—Ratcliffe encourages people to approach listening with understanding, with the intent to understand other perspectives and to better understand the people who hold differing viewpoints.[1]

We believe that the ability to understand a variety of perspectives and then add your educated voice to that conversation is essential to being an engaged and productive citizen. In order to do that, you will need to do quite a bit of research. Before crafting an argument, you must determine your primary research question(s); learn as much as possible about the multiple aspects of your topic; research the values, concerns, and beliefs of your audience; and determine how best to respond. The process of research will often cause you to change your own opinion on a topic; being open to change in the face of new research is a valuable part of the learning process and a critical skill in and of itself.

Finally, we want to note that this is one of the most practical and useful courses you are likely to take during your college career. The very act of writing regularly, of engaging in writing as a practice, will help you improve. Doing this practice with the guidance of your instructor, your peers, and this textbook will further strengthen your ability to express yourself on the page—a requirement for many classes throughout the university. Additionally, employers in nearly all fields consistently report that one of the primary qualifications they look for in employees is good written communication skills. The skills you learn in ENGL 200, then, can literally help you get (and keep) a good job.

ENGL 200 Course Objectives

By the end of the semester, students should have completed at least 20 pages of revised and edited prose. Below, you will find the English 200 course objectives. By the end of the course, you should be able to do the following:

- Adopt effective process writing strategies, including invention, drafting, analyzing your own draft and those of others, revising, and editing.

- Construct an argumentative claim and develop and adequately support audience-based reasons.

- Demonstrate ability to respond thoughtfully to peers’ drafts.

- Identify and apply the core concepts of an explicit argument: claims and audience-based reasons, evidence, assumptions/warrants, credibility, conditions of rebuttal, as well as ethos, pathos, and logos.

- Anticipate and rebut counterarguments to your claims, reasons, warrants, or use of evidence.

- Locate and evaluate appropriate outside research sources and effectively integrate and cite them in your arguments.

- Analyze specific audiences.

- Produce a broad range of arguments for various contexts and audiences: evaluations, proposals, letters to the editor, etc.

Undergraduate Student Learning Outcomes[2]

Kansas State University strives to create an atmosphere of intellectual curiosity and growth, one in which academic freedom, breadth of thought and action, and individual empowerment are valued and flourish. We endeavor to prepare citizens who will continue to learn and will contribute to societies in which they live and work.

Students share in the responsibility for a successful university educational experience. Upon completion of their degree and regardless of disciplinary major, undergraduates are expected to demonstrate ability in at least five essential areas.

Knowledge

Students will demonstrate a depth of knowledge and apply the methods of inquiry in a discipline of their choosing, and they will demonstrate a breadth of knowledge across their choice of varied disciplines.

Critical thinking

Students will demonstrate the ability to access and interpret information, respond and adapt to changing situations, make complex decisions, solve problems, and evaluate actions.

Communication

Students will demonstrate the ability to communicate clearly and effectively.

Diversity

Students will demonstrate awareness and understanding of the skills necessary to live and work in a diverse world.

Academic and professional integrity

Students will demonstrate awareness and understanding of the ethical standards of their academic discipline and/or profession.

Principles of Community[3]

Kansas State University is a land-grant, public research university, committed to teaching and learning, research, and service to the people of Kansas, the nation, and the world. Our collective mission is best accomplished when every member of the university community acknowledges and practices the following principles:

We affirm the inherent dignity and value of every person and strive to maintain an atmosphere of justice based on respect for each other.

We affirm the right of each person to freely express thoughts and opinions in a spirit of civility and decency. We believe that diversity of views enriches our learning environment and we promote open expression within a climate of courtesy, sensitivity, and mutual respect.

We affirm the value of human diversity for community. We confront and reject all forms of prejudice and discrimination, including those based on race, ethnicity, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation, religious or political beliefs, economic status, or any other differences that have led to misunderstandings, hostility, and injustice.

We acknowledge that we are a part of the larger Kansas community and that we have an obligation to be engaged in a positive way with our civic partners.

We recognize our individual obligations to the university community and to the principles that sustain it. We will each strive to contribute to a positive spirit that affirms learning and growth for all members of the community.

Your Role as a Student in an Academic Community

Now that you have joined Kansas State University as a student, you are part of a larger

intellectual community: students, instructors, and professors are researching, creating, and

sharing knowledge and ideas. For instructors and professors, ideas are their livelihood. In a

university environment—also known as academia—ideas are considered intellectual property. Therefore, as members of this academic community you need to be respectful and responsible with another’s ideas and give credit where credit is due. To help you respectfully work with outside ideas in your papers, we will be learning how to cite sources in this course. In addition, in an intellectual community, you need to make sure that all of the work you do for all of your classes is your own. You can review the Kansas State University Honor Code in the Student Life Handbook.

A Word on Plagiarism…

The Council of Writing Program Administrators defines plagiarism as something that “occurs when a writer deliberately uses someone else’s language, ideas, or other original (not common-knowledge) material without acknowledging its source.”

Your Student Life Handbook also includes definitions of plagiarism and gives you advice for when you need to provide appropriate citations:

- Whenever you quote another person’s actual words

- Whenever you use another person’s idea, opinion, or theory, even it if is completely

paraphrased in your own words - Whenever you borrow facts, statistics, or other illustrative material—unless the

information is common knowledge (William W. Watt, An American Rhetoric 8)

Talk to your instructor if you have any questions on how to cite properly. Please also check K-State’s Honor & Integrity System website for more information: www.k-state.edu/honor.

If it is proven that you have deliberately plagiarized a paper in an Expository Writing class, the Honor Council will be notified. Consequences could be severe, including failure of the class, required enrollment in a Development and Integrity course, or, in particularly severe offenses, expulsion from the university.

Expository Writing Program Generative AI Policy

The use of generative AI and LLMs (such as, but not limited to, ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot, and the Generative AI function in Grammarly) on any aspect of any assignment in this class is strictly and expressly prohibited. This includes but is not limited to idea generation, research, note-taking, outlining, summarizing, drafting, revising, editing, responding, and workshopping. Any use of generative AI on any aspect of any assignment is considered plagiarism / academic dishonesty and will be treated as such. You do not have permission to input any class materials, including assignment prompts or lectures, into a generative AI program. The program does not agree to allow its work to be used to train AI programs.

If your instructor suspects AI use on any assignment, they will contact you to discuss this issue and, based on that conversation, determine next steps. If your instructor suspects a second use of AI, they will file an Honor Code violation with the Honor & Integrity Council. If your instructor suspects AI use on the final essay assignment, because it is the end of the semester, you will earn a 0 on that assignment. If you would like to challenge that grade, please contact your instructor so they can submit the essay to the Honor & Integrity Council as a suspected Honor Code violation. You will then be able to present evidence at the subsequent Honor & Integrity Council hearing.

Introductory Assignment

The start of the semester, before the major assignments begin, is a useful time to get to know each other a little better through a brief writing assignment. The purpose of this activity is to demonstrate your awareness of argumentation while also introducing yourself as a writer to your instructor and to the rest of your writing community (your classmates). While this assignment is ungraded, you should view it as an opportunity to showcase your critical thinking and writing skills before the graded work of the semester begins.

To complete the activity, write a 600-900 word (typed, double-spaced) essay that explores a situation in which you either were or were not successful in persuading an audience (a parent, a friend, a co-worker, etc.) to act upon, agree with, or believe a particular idea. Or perhaps you convinced someone to simply consider the validity of a viewpoint that they’ve generally resisted. You should think of your essay as an argument, too: you’re making and supporting a claim that you were or not successful in the situation you describe. Remember to include clear evidence that illustrates your main claim.

Here are some invention ideas to help you get started:

- What formal and informal groups/organizations/communities do you belong to?

- What controversies/disagreements/issues exist within these groups?

- What were/are your ideas about these issues? Did you participate in any discussions

about them? What opinions, facts, and/or other reasons did you offer in those

discussions? - Whom did you try to persuade?

- Were these attempts formal (addressed to governing bodies, for example) or informal,

addressed to family, friends, or colleagues? - Were you successful in your argument? Why or why not?

What is Argumentation?

In this textbook and throughout ENGL 200, we are going to challenge the definitions of this meme by Peace Maker’s Life:

We are not going to separate discussion from argument or define argument as only a way of sorting out winners—“who is right”—from losers. Instead, we hope to present a view of argumentation that is a process of discussion, research, and inquiry.

In ENGL 200, we focus on the audience, our readers. Instead of expressive, informative, or imaginative writing, our main purpose will be argumentative writing. In short, you will be making argumentative claims and supporting them with reasons and evidence to shape the thinking of your readers and, quite possibly, move them to action.

As you progress through ENGL 200, you will become aware of all of the arguments that saturate your everyday life. Companies, government entities, non-profits, educational institutions, advertisers, websites, social media sites, and public citizens—not to mention your own friends and family members—will be vying to get your attention, trying to get you to agree with them, to change your mind, to identify with them and their causes, and to move you to act (e.g., to vote in a certain way or to donate money).

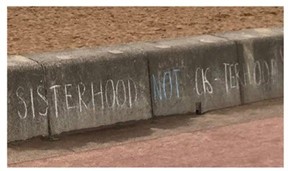

In the following three images, you will find examples of grassroots arguments that point to issues important to large communities and audiences. Each of these arguments, moreover, have a larger social and cultural context.

What are the characteristics of these three arguments? The authors in all three have a persuasive purpose. Instead of simply expressing themselves, informing their readers, or making a literary contribution, they are attempting to persuade their audiences. That is, they want to persuade their readers to pay more attention to an issue (e.g. the refugee crisis in Europe), to change their minds, or to move them into action.

These arguments are also attempting to initiate a conversation; they are not combative and angry. They are also reaching out to a public audience, which could be supportive (they agree with the position), neutral (they are undecided about the issue), or resistant (they hold an alternative position). Importantly, these arguments refer to larger social contexts that these public audiences will be invested in. However, this is not to say that all people will respond to or care about these arguments. The “Policy & Change” yard sign, for example, restricts itself to adult audiences in the United States and may attempt to provoke a religious-based audience. “The Sisterhood, Not Cis-terhood” argument invokes those with particular interests in gender identity rights, feminist and transgender studies, and LGBTQ issues.

To clarify this discussion, let’s list the four main features that reflect how argumentation will be defined in this textbook:

Persuasion & Dialogue

Argumentation consists of a rich interplay between persuasion and dialogue. On the one hand, your purpose is to shape the thinking of your readers, to change their minds, and to move them into action. The “authors” of the “Policy & Change” yard sign, for example, are hoping that their audiences will consider gun reform legislation. On the other hand, you should use argumentation as a way to learn more about your issue, your message, the writing strategies available to you, and your audience’s needs and values. In short, instead of a “fight” or a pro/con debate, you are encouraged to regard argumentation as a dialogue with your readers and as a process of truth seeking. You should work toward a fuller understanding of the issues you are addressing and be willing to change your mind about them and consider alternative claims and reasons.

Explicit Claims and Reasons

As you work on arguments in this class, you will offer explicit claims and reasons. Unlike the authors of the three arguments that we discussed above, you will be asked to highlight your main claim for your readers—this is the position that you are supporting about the issue. You will then support this main claim with reasons—statements that support and justify (explain “why?”) your position. Instead of “Refugees Welcome,” therefore, your argument would more clearly specify your claim and reasons:

Claim: We should welcome all refugees to Italy.

Reason #1: Because they are human beings deserving of a better life.

Reason #2: Because we need to create a world that is more sustainable and equitable for all.

Reason #3: Because Europe has the wealth and capacity to care for all refugees.

When you make your argument explicit, you are trying to make it as easy as possible for your readers to understand your position and the reasons why you have taken that position. Here are some more examples of explicit arguments:

- K-State Libraries should not feature a café in its first-floor space because it makes the library appear too much like a place for shopping and entertainment.

- The online class I took last semester was a disaster because the instructor stopped communicating with everyone halfway through the semester.

In both of these examples, the writers have clearly indicating what they were arguing, a proposal not to do something in the first case or a negative evaluation in the second; the writers have then supported and justified their positions with an obvious reason.

Public Audiences

Your arguments should have a “public” audience—that is, there needs to be a reasonably large public community or communities that are invested in the issue and are interested in exploring it. The issue should not require a great deal of technical knowledge or expertise for members of these public communities to participate in it. Similarly, the issue should not be of interest only to one small community that is not connected to the larger interests of public life.

Issues surrounding parenting are a good example of public arguments. Not only do many people become parents, and thus find themselves having to confront these issues, but all people as children will be affected by these arguments. Here are several parenting issues that are commonplace: parenting styles, breastfeeding, types of punishment, use of television and digital devices, and homeschooling. Similarly, the issues related to vaccinations and “anti-vaxxer” parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated are now frequent arguments with many consequences for healthcare and schooling.

Unfortunately, there are some audiences for which it is impossible to generate a persuasive, successful, and ethical argument. These are audiences who may resist your attempts at creating a dialogue and searching for the truth and good solutions. Here are three audiences to avoid:

- Polarized audiences: When writers attempt to appeal to audiences who may be resistant or openly hostile, they may encounter rhetorical situations in which effective argumentation becomes impossible. In these cases, the polarized audiences reject the assumptions and values held by those with alternative perspectives and, in effect, refuse to listen to reasoned arguments. Issues related to abortion, gun rights, and conspiracy theories may include highly polarized audiences.

- Audiences who do not want to change: If your readers refuse to consider the possibility of changing their minds or agreeing to compromise, then the conditions of successful argumentation are no longer possible. Similarly, as the writer and arguer, you must also open yourself up to the possibility of changing your mind about the issue.

- Audiences who hold no basis of agreement with the writer. If the writer and their audiences refuse to grant their reasons and evidence any validity, then there is also no basis for successful argumentation. For example, writers who craft arguments based upon conspiracy theories or readers who disregard all evidence as “fake news” will not be able to participate in argumentation in the ways in which it has been defined here.

Controversial Issue

The issue you choose to explore should be “controversial,” which, in this case, means a topic that includes at least two perspectives or two ways of thinking about it. In other words, you need to conceive of at least two groups of readers who would hold alternative views about the issue and position themselves differently.

When we discuss controversial issues, it is important to distinguish between issues—topics on which at least two groups of people disagree or have different perspectives—and informational questions, those research questions and answers that most (reasonable) people will agree with. In other words, you won’t be arguing about informational questions, such as the following:

- When has the warmest temperature been recorded in Antarctica?

- What percentage of high-school students in the United States have reported eating disorders?

- According to voter data in 2025, how many voters identify themselves as “white nationalists”?

- What are the differences in standardized language test scores between different demographic groups?

Instead, as you approach arguments, you’ll be thinking in terms of issues:

- Why has the U.S. government been slower than Scandinavian countries in recognizing the relationship of climate change and rising temperatures in Antarctica?

- What role does the fashion media have to play in eating disorders among adolescent girl and women in the United States?

- Why do so many young white men now call themselves “white nationalists”?

- How can we help support the lower test scores of young males when it comes to language development?

Activity: Defining Argumentation

Discuss whether these following argumentation scenarios meet the ways in which argumentation is defined in ENGL 200. If they are not arguments that fit the specific contexts of ENGL 200, consider how you would revise them to better reflect the approach to argument we’ve been outlining.

- In this Unit 3 persuasive research paper, I am going to finally prove to all that the 9-11 attacks on the Twin Towers were part of a right-wing conspiracy to entangle the United States in the Middle East for decades and make owners of oil fields and weapons factories wealthier.

- In the Midwest of the United States, temperatures in the wintertime have been increasing over the past ten years.

- The Obama-era restrictions on lunches in public schools need to be modified to help offset food waste.

- Nothing will ever get me to change my mind that the United States is a nation of immigrants, and all immigrants—no matter how they arrived in the country—should have the chance of becoming citizens.

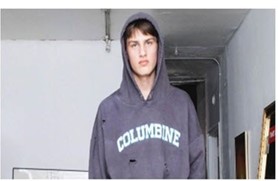

Activity: Example Bstroy Hoodie Argument

Based upon this discussion on argumentation, look at this list of tweets that respond to a new clothing line by Bstroy, in which hoodies show the names of schools involved in mass shootings and include “bullet holes.” Choose three of the tweets and present the argument that they make in your own words. Then, discuss whether these tweets meet the definition of a viable argument for ENGL 200.

- Dragon Poo @StarkAssNaked: Creativity can (and should) be original, sometimes brash, and sometimes controversial. #bstroy school shootings hoodies are none of those…just a selfish gimmick from a couple of hacks better suited to selling fake Rolexes in Times Square.

- John Harvey @digitallywired: Despicable. Designers of ‘Sandy Hook’ and ‘Columbine’ hoodies made an awful blunder (Opinion).

- Julia Mayhem @pipzt3r: If #Bstroy said “hey all of these funds are going toward supporting the victims, family of victims, and communities affected by these tragedies,” I’d be so down because these images, and art in general, can be used to send a powerful message.

- Reina Sanchez @ReinaSa43116912: Trying to make a “statement” in the hopes of achieving a pay day using the souls of innocents is truly despicable. Your brand turns my stomach and shows the worst of humanity. #bstroy

- CSMingus @CSMingus #mediawhorespotlight: And how much money is being made? Their T-shirts sell for $135. Their hoodies range from $180 to $410 each. Proof that “fashion” is overrated and a complete joke.

Activity: Local Arguments

Find and photograph as many arguments that you see in your immediate “linguistic landscape,” the public space in the local area that you interact with and walk through every day. While doing so, make sure that you are paying attention to all of the possible genres in this landscape: bumper stickers, T-Shirts, pins and badges, sidewalk chalk art, flyers, billboards, graffiti, yard signs, company signs, and other possibilities. Be prepared to talk about the claims and reasons that appear in these arguments and whether they fit the ways in which argumentation has been defined above.

Here are two examples of local arguments:

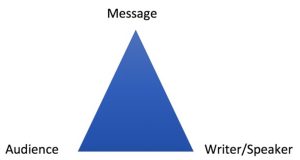

Rhetorical Situation of an Argument

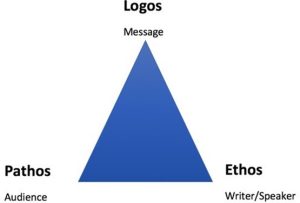

The basic rhetorical situation of an argument consists of three major components: the writer/arguer, the message/text, and the reader/audience. The writer crafts an argumentative message that they want to get across to the audience. The relationship of these three interlocking terms is often visualized as a triangle, sometimes called the “rhetorical situation triangle.”

To show the rhetorical situation in action, consider the ubiquitous example of the warning or safety sign. This is a highly visible argument—one that you come across a lot. In this case, the individual or institution that installs the sign becomes the “writer” of the argument: even though they may not have produced the sign itself, they are the ones who are taking responsibility for its message. For example, here is a sign found on a public path by a field of horses:

The message of the sign is simple: passersby should not feed the horses, because doing so could harm them. Indeed, we might almost want to consider this an informative statement: the writer is informing their audience about the dangerous consequences of feeding horses unapproved and unauthorized food. Yet, this claim is nonetheless an argumentative one, one that seeks to persuade its audience to change their behavior.

Who is the audience for this sign? It is tempting to think of the audience as all possible readers who may see this sign, yet it’s often more useful to consider the intended rhetorical audiences: the readers who were imagined when the sign was created and, of course, when the sign was installed. The question you have to ask yourself is whether the writer primarily conceived of their audience as resistant—passersby who enjoy feeding the horses without permission—or if the writer has in mind a supportive audience (people who would already affirm the sign’s message). Of course, the writer may be holding both of these audiences in mind at the same time.

As we analyze this apparently straightforward message, it is also important to recognize the issues that surround its argument, including expectations for public behavior, attention to animal welfare, and the reasons why people might choose to feed an animal that they do not own.

Unpacking Rhetoric

The issues and approaches we’ve been detailing so far fall within the realm of rhetoric. In fact, ENGL 200 is, at heart, a class in rhetoric; in other words, it is a class devoted to having you consider the ways in which you—and others—are purposefully using language and other symbols to influence readers, viewers, and listeners. Researchers in rhetoric study a wide variety of things: from tattoos to speeches, building design to Reddit threads, and clothing to sidewalk chalk. For example, some rhetorical scholars study how museums and memorials affect participants by analyzing architectural forms, messages, digital instillations, display objects and artifacts, and images. Researchers in technical communication and rhetoric may examine how medical instructions and packaging downplay the risks for consumers. Likewise, other scholars in the field may examine how architecture students learn to enact the values of architecture through design proposal assignments.

Rhetoric in Action: Word Choice and Filtering/Emphasis

One important dimension of rhetoric is the way that people use language to shape the world for themselves and for others. Read this following scenario:

A high-school teacher receives an angry email from a parent who accuses the teacher of “confronting” her son in the hallway after class and “scolding” him on the quality of his recent homework assignment.

Confronted? Scolded? Although the teacher recalls briefly meeting with the student after class and suggesting that the student revise his homework to enhance his semester grade, she is worried about how her interaction has been represented. It definitely does not fit into the model of teaching and teacher-student interactions that she has tried to foster throughout the semester.

What is going on here? Well, rhetoric is going on. The mother—and student (after all, we need to know more about how and why the student depicted this event to his mother)—held a different model or schema in their heads about how teachers and students typically interact with each other; in this case, they held an adversarial model, in which teachers “confront” students (not “approached” or “engaged in a brief conversation with,” etc.) and “scold” students (not “remind” or “suggest” or “encourage”). In this case, according to the mother’s email, the teacher has taken over the role of the authoritarian parent. In her email, the mother has chosen particular words, perhaps unconsciously, in order to emphasize certain aspects of the teacher-student interaction and to filter or shape the reality of what happened for the teacher and, presumably, others.

Rhetoric as Manipulation?

Unfortunately, rhetoric has a popular (mis)understanding as an unethical form of persuasion, in which the rhetor (or arguer) is interested in manipulating audiences, using such strategies as lying, obfuscation, ad hominem attacks, exaggeration, and appeals to conspiracy theories, among other possibilities. Whenever anyone claims that something is just “rhetoric,” they are pointing to this narrow popular definition, which means something similar to “spin,” “propaganda,” and ornate words covering untruths. Although it is important to be mindful of these ways of defining rhetoric, you should also be aware that rhetoric has a long history of engaging writers and speakers with ethical ways to present themselves, contribute to their communities, and to use language intentionally to help shape their audience’s beliefs and actions.

Rhetorical Appeals

Traditionally, those who study rhetoric sometimes do so within the framework of the three major rhetorical appeals, drawn from the rhetorical situation: the writer/speaker, message, and audience. These are the three main ways in which writers can make themselves appear persuasive to their readers. They can appeal through their ethos—their ability to present themselves as credible and trustworthy for their readers; or, they can emphasize their logos, the reasonability of their message, their use of evidence, as well as the coherence of their overall argument; finally, they can be persuasive by appealing to pathos, the emotions and imagination of the readers. We discuss each of these appeals in more detail in the following sections.

Below, we can see the ways that the rhetorical appeals align with the three points of the rhetorical situation to help us complete what’s sometimes known as the “rhetorical triangle”:

Ethos

The “ethos” of the argument points to the writer, speaker, rhetor, or designer. When it comes to a successful ethos-based argument, the audience is sympathetic towards it because they find the writer to be credible, likeable, friendly, smart, impressive, or any other of a long list of qualities.

Writers can present their ethos by having credentials that audiences will respect. If the writer is arguing about a medical issue, for example, readers may respond well if the writer has identified themselves as a medical doctor. When trying to figure out whether to vote for an increase in the local education budget, some voters might appreciate hearing from teachers as opposed to politicians.

Writers can enhance their ethos by appearing to be open-minded, well-organized, and knowledgeable. In fact, writing teachers may be judging their own students’ ethos or credibility when they come across typos, formatting problems, citation glitches, faulty paraphrasing, and sloppy citation or references sections. These problems will certainly diminish the ethos of the student writer. Other writers may choose to enhance their ethos by demonstrating their knowledge of the issue and showing that they understand the different sides of the argument. They will need to do this by reading and listening, conducting research, and talking with peers and experts, among other possibilities.

Writers, through their use of language, can also shape the ways in which their readers accept them as credible, trustworthy, and even likeable people. Writers may

- Use inclusive pronouns (e.g., “we”) or other linguistic devices, to make it seem like the writer is including the reader in their argument

- Create a “bridge” between themselves and their readers; for example, if a university athletic director was arguing to cut a sports program, she might create more sympathy for her position by talking about her experiences as a student athlete

- Use specifics and concrete details to show that they have “done their homework”

- Show that they are willing to compromise and listen

Interestingly enough, in contemporary politics across the globe, ethos has become regarded as the most important rhetorical appeal. In the United States, the United Kingdom, and many other countries, citizens are voting for candidates who they like, admire, and respect—yet with very little thought about what these candidates are actually saying or doing.

Logos

Logos points to the soundness of the rhetorical message: What is the core argument that the writer is offering? What is the main claim? What are the ways that they support and justify the main claim with reasons? What are the ways in which the reasons logically relate to the claim? What assumptions, values, and beliefs does the audience have to hold in order to accept the core argument?

In short, logos is the reasonableness of the argument. Will it make sense to the readers? Will they accept it? Will they be able to follow it? Will they grant it as acceptable, appropriate, and logical?

Evidence also makes up a component of logos. To what extent does the writer support their main points or reasons? How satisfying will the readers find this evidence and the ways in which it is used?

Though we will discuss the different components of logos in more detail below, take a quick look at two examples of a core argument. Many readers will accept the logos of the first example.

However, most readers will not accept the logos of the second example.

Example #1: “We should buy a Subaru Outback because it has high safety ratings.” Claim: We should buy a Subaru Outback.

Reason: Because it has high safety ratings.

Assumption: Safety is an important concern.

Example #2: “He’s Brazilian; of course, he’s going to be good at soccer.” Claim: He is going to be good at soccer.

Reason: Because he is Brazilian.

Assumption: All Brazilians are good soccer players.

In Example #1, this argument makes intrinsic sense because of the fact that safety is an important value and concern for many possible audiences (of course, you might find particular audiences in which safety would be less desirable than other qualities about cars, such as speed and sportiness). In Example #2, the logos is based upon a stereotype. Almost all readers would hesitate to accept the logic of this argument.

Pathos

Pathos points to the audience and, in particular, the feelings, sympathies, and imagination of the audience. Oftentimes, we can consider pathos as the “heart” of the argument, as we are interested in how readers feel because of what the writer or speaker is doing rhetorically.

Writers may use heart-wrenching stories to appeal to the sympathies and emotions of the readers. They may, conversely, use statistics and images to stoke the fears of audience members.

Obvious examples of pathos are easy to find, especially in the images used by non-profits or charitable organizations.

Kairos

Though not a part of the traditional rhetorical appeals, kairos refers to the timeliness of the argument. In other words, to what extent will readers consider the argument or issue to be timely and relevant to them?

There are many examples of people with important claims to make who were not listened to because the “advocacy window” (see also the “Overton window”) or the time was not the appropriate one. For example, many environmentalists have been trying to get politicians and the mass public galvanized around issues of plastics and carbon usage since the 1970s. Yet, they found themselves with few audiences who cared because the effects of climate change were not quite yet part of the everyday experiences of people.

On the other hand, seatbelt safety campaigns in the United States are no longer considered to be urgent or necessary. Attitudes towards seatbelt usage have changed dramatically in the past three decades, especially among young men. Because most people in the U.S. now regularly wear their seatbelts, there is little reason to make arguments urging people to do so. In other words, it is no longer the kairotic moment for such arguments.

As a writer, you can enhance your argument by considering kairos and making clear its urgency and immediate importance. In proposals, for example, you may find yourself writing a “Call to Action” section, in which you are highlighting the reasons why your audience needs to act immediately on your proposal to solve the solution. You would be combining both kairos and pathos, as you may be trying to worry your reader about the negative consequences that could happen if they fail to act in a timely manner.

The list below summarizes the three main rhetorical appeals and kairos.

Ethos

- Writer/speaker

- (“character”; credibility)

- Appeal to the trustworthiness and credibility of the writer.

Logos

- Message/Argument

- (“word”; logic, discourse)

- Appeal to the logic and reasonability of the argument, the consistency of the reasons, and the convincing use of support.

Pathos

- Audience

- (“suffering”; emotion)

- Appeal to the imagination, emotions, and sympathies of your readers.

Kairos

- (“time”; timeliness)

- Appeal to the timeliness and relevance of the argument for the audience.

Figure 12. Summary of Rhetorical Appeals

Even though these rhetorical appeals appear in separate columns in Figure 10, please be aware that in practice they can blend together; moreover, when analyzing a specific feature of an argument, you might be able to explain it by referring to more than one of the appeals. For example, consider the use of statistics. During the Covid-19 outbreak, Anthony Fauci, one of the most visible of the scientific advisors in the Trump administration, used the statistic of 240,000 potential coronavirus deaths to galvanize the political action needed to enforce social distancing and isolation policies. As ethos, the use of this statistic shows that Fauci was aware of the scientific data and the modeling that had been conducted; as logos, Fauci used this statistic as evidence to support his claim (social distancing and isolation policies are necessary) and his reason (because they will save lives); finally, as pathos, this frightening statistic affected audiences emotionally; they were persuaded out of fear.

Using the concepts of the rhetorical appeals, examine the following sign. In terms of the rhetorical appeals, how is it different from the “Spot! Please Don’t Feed the Horses” warning sign?

Ethos: What can you say about how this warning sign represents its “writer” as well as the relationship between the “writer” and the “readers”?

Logos: What is the explicit claim of the message? The reason? What is the unstated assumption that readers have to hold to make the connection between the claim and the reason understandable and reasonable?

Pathos: Who is the intended or target audience of this sign? How do you know? How are members of the intended audience meant to feel? What particular details can you select to show how pathos is working?

A Brief Note on Conspiracy Theory Thinking

Although conspiracy theories certainly predate the arrival of Facebook, YouTube, and other social media platforms, as a particular form of argumentation and public discourse, conspiracy theory thinking—what former President Obama has referred to as “truth decay”[4]—has become quite powerful, even commonplace and mainstream. Elite lizard people running the United States? Top Democratic Party representatives involved in a global child sex-trafficking ring? Bill Gates inventing Covid-19 to enable him to implant computer chips into people? 5G Networks sending out signals to sicken or enslave the population? [5] Internment camps underneath the Denver Airport?[6]

Admittedly, the examples above have been chosen because they appear so ludicrous, yet we cannot forget that even these beliefs have real effects. In December 2016, a man opened fire at a pizzeria in Washington D.C., one of the supposed centers of the sex-trafficking ring.[7] 5G towers have been burnt down in Great Britain by “truth seeking” activists. Closer to home, in Manhattan, Kansas, drivers with painted QAnon symbols on their vehicles challenged bystanders after the 2020 presidential election.[8] Another example: traumatized parents of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting have been accused of faking the massacre as a way to sway public opinion against gun rights.[9]

Conspiracy theory thinking has spread as a way to shape the reality—and to resist government policies and official explanations—of traditional political processes such as elections, well-established medical procedures, and public policies, including that of mandating masks during the coronavirus epidemic. Additionally, we should be troubled by the similarities that many conspiracy theories, in particular QAnon, have with anti-Semitic discourse.[10]

A conspiracy theory argument consists of the same elements as the public arguments that we will be exploring in ENGL 200. It consists of ethos—in this case, appeals to an “insider” who has special knowledge (e.g., QAnon) or who may possess academic credentials (e.g., Vanessa Beeley[11]). It is also framed within an audience-focused pathos, using such emotions as fear and disgust, and, more importantly, providing readers and listeners with the satisfying feeling that they are in the presence of the truth and can empower themselves by having the meaning of the world unlocked for them. Finally, conspiracy theory thinking is a form of logos, yet an internal, pseudo-sort of logos: conspiracy theorists do make claims and use evidence to support their reasons, yet they cannot defend their evidence, find credible and external sources of information, objectively examine their own views, and consider other possibilities or alternatives. In fact, it becomes impossible to argue with conspiracy theory thinking. Your criticisms, challenges, and appeals to more credible sources are immediately used to strengthen their claims. British writer James Meek, when he attempted to discuss his concerns with a conspiracy theorist, made this discovery: “I was reminded of one of the reasons it’s so difficult to argue with conspiracy theorists: you’re faced with a choice between challenging limitless errors one by one, or denouncing an entire edifice of belief, which usually means calling the conspiracy theorist mad [i.e., insane] or stupid, at which point conspiracy theory has won” (21).[12]

How can you help to challenge the growing power of conspiracy theory thinking? As a student of argumentation and persuasion, keep on honing your ability to distinguish between fact and fiction and to make judgements about the credibility of evidence; seek out opportunities to share ideas with those who may disagree with you—but who will do so reasonably, productively, and civilly; recognize that the world is far more complicated than these simple conspiracy theories may lead you believe; understand that you nor anyone else holds 100% of the truth—yet at the same time that you can make judgements without falling into the trap of denying everything and claiming everything is “fake news”; support legislation to regulate social media; and, among other strategies, pay attention to the labels, symbols, rhetorical appeals, and other components of arguments that you encounter.

More on Logos: Introduction to the Toulmin Model

ENGL 200 uses the Toulmin Model, named after the British philosopher, Stephen Toulmin, who was interested in showing how logic could become a powerful way for people to unpack issues, argue, and make decisions. The Toulmin Model was popularized in one of the most successful writing textbooks, Writing Arguments.

The Toulmin Model consists of these following terms, some of which we’ve been using already:

Claim

Your main thesis or point; the message you are focusing on.

- Vapes should be banned immediately!

- The iPhone 16 is the best cell phone ever.

Reason

A statement or point that supports, backs up, and justifies your claim.

- Because they have harmed the health of many adolescents.

- Because it includes the most powerful camera with the fastest processing speeds.

Assumptions

These are the beliefs, values, or philosophical positions that logically connect the claim and the reason; although the speaker/writer may not explicitly state the assumption, the readers need to accept this assumption in order for the claim and reason to make sense and sound reasonable.

- Products that harm the health of adolescents should be banned.

- The most important criteria of a cell phone are the camera and processing speed.

When we consider an argument to be sound and valid, it is because we share the same assumptions as the person who is making the argument. In the two examples above, many readers would accept the first claim and reason (though, consumers and producers of vapes may dispute how dangerous these products are). Many readers, when looking at the second example, would dispute this claim and reason; instead, they would assume that other criteria are more important, such as digital security, size, and cost.

Evidence

Evidence includes all of the types of research sources that you are familiar with: academic articles, statistical reports, interview data, testimonies by trustworthy people, stories and anecdotes, and test data, among many other possibilities.

In the Toulmin Model, we can support and develop the claim and reason with evidence, which Toulmin called “grounds.” In the example above about the dangers of vapes, the writer might provide evidence of hospital visits of teenagers that were reported in newspaper articles and in editorials. The writer might also include a personal story from a victim or an important testimony from a respected doctor as evidence that the claims and reasons are true.

Evidence can also be used to support and develop the assumption, which Toulmin called “backing.” In the iPhone example, the writer may support the criteria about the camera and processing speed by finding user reports on the Internet or by finding statistics that show that most consumers use the photography option of cell phones most often. In short, the writer is looking for whatever evidence there is to support the importance that has been placed upon cell phone cameras and processing speed. This writer might benefit from searching the Internet and finding such articles as Chase Buckle’s “Which Smartphone Features Really Matter to Consumers?”

The Toulmin Model can be used to analyze your own arguments and those of others. Read the following article; afterwards, you will find a “reverse outline,” one way of putting this argument into the Toulmin Model.

Toulmin Outline Practice

Please take a look at this following advocacy letter, which is a template produced by the American Veterinary Medical Association. Veterinarians are asked to send in this letter to local governments that may be considering Breed-Specific Legislation as a way to reduce the risk of dog bites; in short, the American Veterinary Medical Association is against banning certain types of dogs—such as pitbulls—from communities.[13] They are hoping to use the credibility of local veterinarians to help counter this type of legislation.

Breed-Specific Legislation Sample Letter from Veterinarian

To Whom It May Concern:

I am writing in opposition to the breed-specific legislation currently under consideration by the <insert agency> as a proposed strategy to prevent dog bites. Policies that target specific dog breeds for increased regulation or outright bans have proven ineffective in improving public safety. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) is opposed to breed-specific legislation and instead advocates for specific strategies that have proven effectiveness in reducing the incidence of dog bites.

While breed-specific laws may look good on the surface, they are an overly simplistic approach to a complex social problem. There are several major problems with breed-specific legislation:

Breed-specific laws can be difficult to enforce, especially when a dog’s breed can’t easily be determined or if it is of mixed breed. It is extremely difficult to determine a dog’s breed or breed mix simply by looking at it. Studies show that even people very familiar with dog breeds cannot reliably determine the primary breed of a mutt. Because of this, breed-specific legislation frequently focuses on dogs with a certain appearance or physical characteristics, instead of an actual breed, making the laws inherently vague and difficult to enforce.

Breed-specific legislation is discriminatory against responsible owners and their dogs. Breed bans assume all dogs of a specific breed are likely to bite, instead of acknowledging that most dogs are not a problem. Breed-specific laws can lead to the euthanasia of innocent dogs that fit a certain “look,” and to responsible pet owners being forced to move or give up dogs that have never bitten or threatened to bite. Furthermore, breed-specific ordinances may be in violation of a dog owner’s right to equal protection.

Breed bans do not address the social issue of irresponsible pet ownership. Any dog can bite, regardless of breed. Dogs are more likely to become aggressive when they are unsupervised, unneutered, and not socially conditioned to live closely with people or other dogs. But breed bans rarely assign appropriate responsibilities to dog owners. Breed-specific legislation deemphasizes the importance of responsible pet ownership, and diverts attention and resources away from proven solutions, such as socialization and training, and licensing and leash laws.

It is not possible to calculate a bite rate for a breed or to compare rates between breeds because the data is often inconsistent or incomplete. Statistics on injuries caused by dogs are often used to demonstrate the “dangerousness” of particular breeds. However such arguments are seriously flawed because: 1) the breed of a biting dog is often not known or is inaccurately reported; 2) the actual number of bites that occur in a community is not known, especially if they did not result in serious injury; 3) the number of dogs of a particular breed or combination of breeds in a community is not known because it is rare for all dogs in a community to be licensed; 4) statistics often do not consider multiple incidents caused by a single animal; and 5) breed popularity changes over time, making comparison of breed-specific bite rates unreliable.

Governmental policies aimed at reducing the incidence of dog bites need to look far beyond breed to identify effective solutions. The AVMA recommends the following strategies:

- Enforcement of generic, non-breed-specific dangerous dog laws, with an emphasis on chronically irresponsible owners

- Enforcement of animal control ordinances such as leash laws, by trained animal care and control officers

- Prohibition of dog fighting

- Encouraging neutering for dogs not intended for breeding

- School-based and adult education programs that teach pet selection strategies, pet care and responsibility, and bite prevention

Please feel free to contact me if you’d like additional information about dog bite prevention or breed-specific legislation.

Sincerely,

Veterinarian

Toulmin Outline

The following outline shows one way of rendering “Breed-Specific Legislation Sample Letter from Veterinarian” in the Toulmin Model, which is a letter rich in logos. This outline only addresses the main reason highlighted in the template letter.

Claim: The local government should not consider breed-specific legislation as a strategy to make citizens safer from dog bites.

Reason: Because these breed-specific policies are not effective.

Assumption: It is important for lawmakers to base their policies on effectiveness.

Evidence for Reason:

- States that effectiveness is a problem because it is difficult to determine the breed of dogs; cites research stating that even experts may find it difficult to determine the primary breed of a dog.

- Provides support that these policies are ineffective because they can be regarded as discriminatory, against both dog owners and the dogs themselves.

- Claims that effectiveness is a problem because it does not get to the heart of the problem—the responsibility of owners.

- Argues that effectiveness is also challenged because it is difficult to generalize a “bite rate” based upon the specific type of dog.

Evidence for Assumption:

- The writers of the AMVA template letter for veterinarians do not develop or justify the assumption, as they will consider “effectiveness” to be a commonsensical belief that their government audience will accept. The AMVA writers are careful to point out that Breed-Specific Legislation and the safety of citizens are complicated issues.

Conclusion: Summary of Key Rhetorical Concepts

Assumption: The belief, value, or philosophical principle that the audience needs to hold in order for the argument to be reasonable and persuasive. Also known as a “warrant.”

Claim: The main stance or message of the writer or speaker; their thesis, perspective, or opinion on an issue.

Controversial: A quality of an issue in which at least two reasonable people disagree and have differing and opposing or alternative perspectives.

Ethos: The ways that writers demonstrate their own credibility and character to persuade readers.

Logos: The logical structure of the argument, including the claim, reasons, assumptions, and evidence.

Evidence: The strategies and sources in which writers support their claims, reasons, and assumptions.

Pathos: The ways in which writers appeal to the feelings and emotions of readers to be persuasive.

Kairos: A persuasive quality of an argument, depending on how timely the issue is for the audience.

Public Audience: Readers and listeners (and viewers and users, etc.) who participate in a broad range of issues and communities.

Reason: A statement that supports or justifies the claim; it explains why the writer holds the claim.

Rhetoric: The intentional use of language and symbols to communicate something.

Rhetorical Situation: The context of the argument, which includes the writer, their readers, the writer’s message and purpose, the genre (the type of writing), and other social and cultural factors.

- Ratcliffe, Krista. Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2005. ↵

- From Kansas State University <https://www.k-state.edu/assessment/reporting/institutional-learning/undergradobj.html> ↵

- From Kansas State University www.k-state.edu/about/community. ↵

- Budryk, Zack. “Obama: Trump has Accelerated ‘Truth Decay.’” The Hill, 16 Nov. 2020, https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/526097- obama-trump-has-accelerated-truth-decay. ↵

- Tiffany, Kaitlyn. “Something in the Air.” The Atlantic, 13 May 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2020/05/great-5g- conspiracy/611317/. ↵

- Bailey, Cameron. “Denver International Airport Conspiracy Theories and the Surrounding Facts.” Uncover Colorado, 19 April 2020, https://www.uncovercolorado.com/conspiracy-theories-denver-international-airport/. ↵

- Sebastian, Michael, and Gabrille Bruney. “Years After Being Debunked, Interest in Pizzagate Is Rising—Again.” Esquire, 24 July, 2020, https://www.esquire.com/news politics/news/a51268/ what-is-pizzagate/. ↵

- Moser, Megan. “Man Who Knelt Said He ‘Had to Do Something’ when he saw QAnon Symbols in Parade.” News Break, 15 Nov. 2020, https://www.newsbreak.com/kansas/ manhattan/news/2103041818240/man-who-knelt-said-he-had-to-do-something-when-he-saw-qanon- symbols-in-parade. ↵

- “This Sandy Hook Father Lives In Hiding Because of Conspiracy Theories Fueled By Alex Jones.” Frontline. PBS, 28 July 2020, https://www.pbs. org/wgbh/frontline/ article/ this-sandy-hook-father-lives-in-hiding-because-of-conspiracy-theories-fueled-by-alex-jones/. ↵

- Greenspan, Rachel. E. “QAnon Builds on Centuries of Anti-Semitic Conspiracy Theories that Put Jewish People at Risk.” The Insider, 24 Oct. 2020, https://www.insider.com/qanon-conspiracy-theory-anti-semitism-jewish-racist-believe-save-children-2020-10. ↵

- Solon, Olivia. “How Syria's White Helmets Became Victims of an Online Propaganda Machine.” The Guardian, 18 Dec. 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/ world/ 2017/ dec/18/syria-white-helmets-conspiracy-theories. ↵

- Meek, James. “Red Pill, Blue Pill.” London Review of Books, vol. 42, no. 20. 22 Oct. 2020, pp. 19-23. ↵

- American Veterinary Medical Association. “BSL Sample Letter from Veterinarian.” AVMA Member Toolkit, 2021. https://www.avma.org/resources/pet-owners/why-breed-specific-legislation-not-answer. ↵