3 Writing Persuasive Research Essays or Open Letters

The purpose of the persuasive research essay is to focus on a controversial issue and then write a multisided argument that attempts to persuade a resistant, or at least highly skeptical, audience to consider accepting your claim. Why will your argument be multisided rather than just one that reflects only your point of view? As a member of a diverse society, you’ll often encounter moments of disagreement and misunderstanding. It’s crucial in these moments that you’re able not only to simply voice your opinion, but also to understand the viewpoints of those who do not agree with you. Doing so helps us avoid unproductive disagreements. At a more structural level, those in power (whether a supervisor at job site, the head of a local governing committee, or even the president of the United States) must listen to a number of credible points of view in order to make the most just and fair decisions about policies and procedures.

On all levels, a multisided argument is simply more persuasive for a resistant audience than a one-sided argument is. One-sided arguments are good at rallying support for those who already agree; multisided arguments, and especially delayed-thesis arguments, are much better at persuading those who hold different views than the rhetor. Multisided arguments often work toward consensus and compromise, focusing on being partners in dialogue with those who hold alternative views, seeking common ground that lessens the risk (or threat) of disagreement. This assignment provides a platform to explore a compelling social or political issue that matters to you and to gain experience in a type of persuasive writing that likely will have practical benefits to your professional and civic life.

While this chapter will take you through more detailed steps to help you write your persuasive research essay, here are a few guidelines to consider at this beginning stage:

Audience—Make sure that you identify an audience that is resistant to, or at the very least skeptical of, the claim you are making about a controversial issue. You may want to imagine that you are writing to an organization or community group that has something at stake with the issue you are raising so that you are able to hold a specific and vivid impression of them as you write. We’ll ask, too, that you list your resistant audience at the top of your research essay submission.

Significance and Focus—Controversial topics are ones that present complex issues that hold more than a “yes” or “no,” or “right” or “wrong,” response, and ones whose outcomes matter deeply to your audience (and to you). You will need to narrow your issue, though, to an angle that is manageable for a short research paper. Huge topics, such as “American Foreign Policy” or “Technology,” are much too broad for the scope of this essay. However, finding a manageable angle to explore, like “America’s use of diplomacy in Iran” or “driverless cars and highway safety,” might work.

Rebuttal Strategies and Audience-Based Reasoning—Because your audience is resistant, you will need to work harder than in previous assignments to demonstrate that you understand their position, and to anticipate what their objections might be to your claim, reasons, assumptions, and source use. You’ll need to make sure you’re using audience-based reasoning throughout your essay in order to most effectively persuade your resistant/skeptical reader.

Research and Documentation—Your outside sources will be important for building your own ethos and for helping to control the development of your argument. So, just as you have been doing in the previous essays, carefully evaluate the credibility of your sources and integrate them into your essay. You should be prepared to undergo an extensive research process since you’ll be working to understand your issue from many perspectives. While your instructor will set their own requirements about the number and type of sources, it’s hard to imagine being successful in this assignment with fewer than five credible outside sources; indeed, you might be required to include far more.

It might be helpful here to consider some examples of a multisided argument. Here’s one from the professional academic world: Katherine Hayhoe, a professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas Tech, hopes to persuade conservative, evangelical groups that climate change is real and that action needs to be taken immediately. Hayhoe reports that approximately 65% of the evangelical audience that she is trying to persuade does not believe in climate change. In order to start to persuade this skeptical audience, Hayhoe emphasizes the need to take care of the planet—what she calls the “stewardship message”—as well as the values she holds in common with them: “We all want a better world for our children, we all think it’s good to conserve our natural resources and not be wasteful, we all want to be able to invest in our economy and not be held hostage to foreign oil.” These values will act as the starting points for her to create reasons that her resistant audience will be willing to listen to.

Another example is from an ENGL 200 class. A student writing an essay for a local restaurant association hopes to persuade restaurant owners to require that nutritional information be added to their restaurant menus. Several members of the restaurant association may be skeptical or resistant about this idea because it means more work for them, including the need to redesign their menus, and they also may be worried about a drop in profits if customers are aware of how unhealthy certain popular menu items are. The writer, therefore, needs to find reasons that will allow for some common ground between him and the skeptical members of the restaurant association. As he formulates his reasons, he decides that his audience will be interested in presenting an image of healthy and wholesome food for customers as that will demonstrate care for their patrons. His persuasive research essay will argue that the restaurant association will not lose money because they will be able to attract more customers with the transparency of their menus’ nutritional information.

As you think about potential audiences and topics, keep in mind that your persuasive research essay will be between 1500-2000 words (the equivalent of 5-7 double-spaced pages, in standard 12-point font). Additionally, we’ll encourage you to use a delayed-thesis structure for this multisided argument, as this form is typically the most effective for persuading a resistant audience. Finally, as you may be asked to write a formal proposal later, in which you ask an audience member to take a particular action, for this assignment, while you might include a brief call to action at the end of your essay, your focus should be broader than that of a specific problem for a workplace or local community; your purpose, moreover, will be more focused on changing minds at the policy level.

When you submit your persuasive research essay, it is a good idea to identify your intended audience explicitly for your readers (e.g., by writing your intended audience down at the top of the first page); identifying your intended audience will not only help your instructor and colleagues evaluate the effectiveness of your audience-based reasoning but will also serve as a good reminder to you that you are reaching out to your resistant and skeptical audience and negotiating differences in values and beliefs.

The Open Letter

Alternatively, your instructor may ask you to write an open letter, an intriguing way to deliver your persuasive research goals to a skeptical audience. The open letter can be especially effective in that you are imagining that you are writing to only one reader or a small group of readers, which allows you to become more personal and interactive. At the same time, an open letter, even though it may be addressed to only one reader, is designed to be read by the larger public. Famous open letters like Émile Zola’s famous “J’Accuse..!” (accusing the French government of anti-Semitism and corruption in the 1890s) or Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” (emphasizing the need for nonviolent action) helped shape public attitudes and political debates. More recently, CEOs of large American corporations, such as Steve Ells of Chipotle and John Schnatter of Papa John's, have taken to the open letter to mollify angry customers and defuse company crises (these corporate open letters can also serve as elegant forms of advertising).

When writing an open letter, find a stakeholder audience, someone who is prominently connected to an issue and who presents a skeptical or resistant position to yours. While writing to this specific reader, you will then imagine that you are also writing to many more readers who you will need to persuade. For example, if you are hoping to reduce the influence of the National Football League, given the violence of the game, you might address Roger Goodell, the NFL Commissioner, but you must also consider football fans across the nation as you craft your argument. If you are writing about the need to regulate social media companies to deal with cyber-bullying among adolescents, you might consider Mark Zuckerberg, the co-founder of Facebook, but must also keep in mind all those users of Facebook, as well as people who do not believe in these forms of regulation.

Objectives

By the end of this unit, your Persuasive Research essay will be able to:

- Explore multiple perspectives of a controversial issue

- Summarize fairly a resistant audience’s perspective on a controversial issue

- Provide common ground between the writer’s views and the audience’s

- Develop persuasive claims with reasons, assumptions, and evidence/research

- Identify, evaluate, and integrate credible research sources

- Document and consistently cite research sources

Beware of these common Persuasive Research essay weaknesses:

- The writer chooses an issue or topic that is not controversial, or that is too broad for the scope of the assignment, or that is not significant to either the writer or reader.

- The writer chooses an issue or topic that is too controversial and therefore will be unable to find common ground or persuade the resistant audience.

- The writer does not demonstrate understanding of the intended audience, and therefore does not anticipate how that audience will resist the essay’s claims.

- The writer uses reasons and evidence/research that are not based on the values and interests of the resistant audience.

Writing to Persuade Skeptical or Resistant Audiences

Writing for audiences already in agreement with you is a relatively easy task: you can rely on one-sided arguments, choose research that your audience already expects and respects, and easily accommodate the beliefs and values of your readers or listeners. In many ways, you are not actually arguing but stoking your audience’s enthusiasm for the issue and your position.

However, if you are thrown into a rhetorical situation in which you have to consider skeptical or resistant audiences, you’ll need to contend with many significant rhetorical constraints. To start off with, you need to grapple with the various perspectives on the issue (multisided argumentation); understand your audience’s positions, beliefs, and values; consider research that counters your position and find ways to respond to that information; shape your ethos to make you a more trustworthy and sympathetic writer for your readers; find moments of common ground and compromise; and imagine ways to use pathos-based appeals to reach your readers.

The difficulty of addressing skeptical and resistant audiences can be found in popular adages or sayings. If we are “preaching to the choir” in one-side arguments (with audiences that are in accord with our positions), what are the similar sayings for dialogical arguments?

A few have negative connotations of the audience: “Casting pearls to swine” (imagining your arguments as “pearls” and your audience as “swine” may not be the best way to plan for persuading them); similarly, “Talking to a fence post” and “Banging your head against a wall” may depict opposing audiences in ways that are not useful for you. “Leading a horse to water” is a good possibility, as it shows that good persuasion is similar to good teaching. “Winning hearts and minds,” meanwhile, summarizes pathos- and logos-based persuasive strategies. All of these phrases make clear, though, that persuading a resistant audience is more difficult than addressing an audience who already agrees with you.

Here is one recent example of an attempt to approach skeptical readers. Alarmed by the competition of plant-based meat substitutes, meat producers have been grappling with ways to reach resistant consumers through appeals to organic and natural values: in short, eating meat is more “natural” than eating plant-based meat alternatives. The conservative consumer organization, The Center for Consumer Freedom, addresses readers who may be tempted by these plant-based substitutes:

Are the chemicals in fake meat harmful? Probably not. But many people want to avoid them anyway. So if fake meat companies or their marketing surrogates tell you fake meat is natural and healthy for you and your family—make up your own mind about whether that’s true.[1]

In this example, The Center for Consumer Freedom is reaching out to, quite possibly, more liberal consumers and parents, those who may be looking for meat alternatives for environmental reasons; these very same readers, though, will be interested in healthy, “natural,” and “organic” alternatives; they may find the focus on “chemicals” a good rationale for steering away from plant-based substitutes.

Depending upon the level of resistance of your audience, you may decide that persuasive strategies will not be useful. For especially hostile audiences, you can only hope to make them more open for persuasion in the future. Therefore, instead of offering an argument that they will immediately reject, you might use a dialogical or invitational approach: you pose questions, tell stories, and try to get them to reflect on their own values and beliefs and to at least better understand alternative viewpoints, even if they don’t agree with them.

And, here’s some bad news. According to Ezra Klein in Why We’re Polarized (2020), Americans are getting more and more entrenched in their own views and becoming more unwilling to listen to views and opinions that are different from their own. Consequently, the rhetorical strategies of this chapter and in ENGL 200 are extremely important for you to consider. Learning how to communicate across difference is a crucial skill, not only in college, but in the workplace and in society more broadly.

Invention Activity: Finding a Topic

Let’s begin with how this assignment relates to you. With your classmates, think about everything you know about controversial issues in the world on the local, state, national, and global level, and generate a class list.

Using that class list as a reference, think about each topic from an individual level (as a student, as an employee, etc.). What are some topics that you relate more to on an individual level? Which do you want to find out more about? What are some potential angles of vision you might bring to those topics?

Then, with that same list, think about each topic from the public level (as a citizen, as a political activist, etc.). What are some topics that you relate more to on a public level?Which do you want to find out more about? What are some potential angles of vision you might bring to those topics?

What two topics do you most want to find out more about? Write them down. Then, use the four following questions to challenge these topics. If you answer negatively to any of these questions, then you should strongly consider revising or changing your issue.

- As the writer, would you be willing to change your mind about your position?

- Is your issue a controversial one? Does a skeptical or resistant audience exist?

- Is there the possibility to establish some common ground between your position and that of your skeptical readers?

- Does the argument have significance for a larger public audience?

Invention Activity: Exploring and Narrowing an Issue through Research

Once you have decided upon your potential issues, you’ll want to read a variety of credible sources to help familiarize yourself with the issues more comprehensively. Keep careful notes, such as in a reading log, and try to find ways to find connections or patterns in these sources and, ultimately, put them into conversation with each other.

While you are researching, track the ways that you see different researchers agreeing and disagreeing with each other. Based upon what we already know about logos, your sources may

- agree or disagree about the facts, definitions, statistics—anything about the "reality" of the issue

- agree or disagree about the underlying values, beliefs, and assumptions of the issue

Use your research notes to track these moments of agreement and disagreement and to clarify your understanding of the issue as a whole. Be sure to record your research citations as you will be expected to cite your sources later in the writing process.

While you are taking notes on your research, these are questions you can ask yourself:

- What would writer A say to writer B? To C? D?

- After I read writer A, I thought _____; however, after I read writer B, my thinking on this issue has changed in these ways: .

- To what extent do writer A and writer B disagree about facts and interpretations of facts? Writer C and D? Or C and B? D and A?

- To what extent do writer A and writer B disagree about underlying beliefs, assumptions, and values? Writer A and C? B and D?

- Can I find any areas of agreement, including shared values and beliefs, between writer A and B (and C and D and E)?

- What new, significant questions do these texts raise for me?

- After I have wrestled with the ideas in these texts, what are my current views on this issue?

As you explore your issue, you may find it useful to discuss your findings and ideas with other people. Such discussions often reveal insights of your own and provide access to new information and suggestions.

Reviewing your research notes will help prepare you to introduce your issue, define/describe it, and explain why you find it a significant matter. Your classmates, instructor, tutors, and others are good people to dialogue with.

Invention Activity: Choosing and Analyzing Your Audience

Once you have settled on a topic, you must identify a specific resistant audience for your essay. This audience might be one who has a prominent voice in your issue’s conversation and whom you would like to engage directly (similar to Chapter 2) or it might be a collective set of readers who belong to an organization representative of your opposing view (PETA members, for example, would be a resistant audience for someone advocating luxury furs). While you likely already have that reader in mind from your initial research—maybe a particular text or author from your bibliography, or a key organization or group that your research has already revealed—take a minute to reflect and make sure that it is a person engaged in your issue who holds a sharply different perspective than you but one with which you believe you can find some common ground. Then, conduct any additional research on this audience so that you can find enough information to answer these questions:

- What does your audience have at stake when it comes to your issue? Why is it important to them? Why would they be interested, therefore, in reading what you have to say?

- What position does your audience hold regarding this issue? How is this position different from yours? Why do you think they hold this position? That is, what reasons do they have, or what values or assumptions do you need to be aware of? (Note: if possible, you may want to find a mission statement or some evidence of what your audience values.)

- List at least two reasons with which your audience supports their main viewpoint about this issue. How can you respond to these reasons? How will your audience accept your rebuttals?

- What assumptions underlie the audience’s own argument regarding this issue? What evidence does the audience rely on to support those assumptions? What are points of agreement, or areas of common ground, that you share with your audience? (Note: if you hold nothing in common, your essay will be impossible to construct.)

- What type of research and outside sources do you think your audience expects and respects?

Audience Analysis

These questions will help you analyze your audience and enable you to plan your persuasive draft more effectively. Take notes on the following questions to get a better sense of your readers:

- What is the exact purpose of my argument?

- What is my audience’s purpose in reading my argument?

- Am I writing to a single or multiple audience?

- Exactly who are my readers?

- Do my readers belong to any definable groups: age, sex, race; socioeconomic or educational level; geographic, religious, occupational, or political background?

- What identifiable characteristics or values do my readers share?

- Which of these group memberships, characteristics, or values are relevant to the purpose of my argument?

- What is the extent of my readers’ knowledge about my subject?

- Given my readers’ level of expertise, what information must I include and what should I withhold?

- What are readers’ likely beliefs about my subject?

- What are the likely causes of these beliefs?

- Must my communication reinforce or counter these beliefs?

- With what predictable expectations are my readers likely to approach my argument?

- Are these expectations positive or negative, and what allowances must I make for these expectations in my argument?

- How credible am I likely to appear to my readers?

- Must I make a special effort to improve my credibility?

- What are my readers’ precise interests?

- How can I best write to my readers’ interest in order to achieve my purpose?

- What rhetorical and organizational choices must I make based on this information about my audience?

Logos: Audience-Based Reasoning

The most important rhetorical strategy in this chapter is to understand your skeptical or resistant audience:

- Why do they think differently from you?

- What reasons do they find persuasive, and why?

- What assumptions do they make—what values, beliefs, principles, and attitudes do they hold that you need to be aware of?

- What kind of evidence and sources do they find appealing and trustworthy?

For example, imagine that you watched Joaquin Phoenix in Joker, and you thought it was one of the best films that you’ve ever seen. Yet, when you look at some of the reviews online, you discover that many viewers hated this film. If you were going to try to persuade them to think again about Joker and recognize its greatness, you would need first to consider what drew them to this negative evaluation of the film. Just conceiving of your audience as “people who didn’t like Joker” won’t be helpful for you.

Instead, you’ll want to read and listen for their reasons and assumptions for why they evaluated this film so negatively, which could be:

- Joker glorified violence

- Joker made a direct correlation between mental health and criminality, which is an unethical position

- Joker was marketed as part of the DC Comics franchise, yet it had little to do with the comic book series and the previous versions of Batman

You then may come up against three different types of audiences, each of whom are resistant to your positive evaluation of Joker for different reasons—and, these audiences may each hold far different values and beliefs. For example, the skeptical readers who felt that Joker was not treated enough as a comic book villain may have no qualms about comic-book violence or about the depiction of characters with mental health problems. You’d therefore need to construct your argument—your reasons, your evidence, your assumptions—differently for each audience.

Activity: Matching Claims with Resistant Audiences

When you are conceiving of your skeptical or resistant audience, try to fully understand who this audience might be comprised of.

Example Claim: Video games can make teenagers violent and aggressive.

Who would be a skeptical or resistant audience for this typical argument? In short, who would question or dispute whether video games have this connection to violence and aggression?

- Programmers and video game company executives (obviously)

- The video-game-playing teenagers themselves?

- Many parents and sociologists who claim that the sources of violence and aggression are much more complicated and deep-seated

- Academic researchers who dispute the link between video games and violent behavior; indeed, they may claim that video games actually make a society safer— as they keep young males off of the streets.

For these following issues and claims, try to come up with a few skeptical or resistant audiences. Then, justify your choices. Who are these people, what are their values, and what organizations or communities might they belong to?

Issue: Community bans on certain breeds of dogs

Claim: We should allow all breeds of dogs (e.g., pit bulls) into our community.

Skeptical or Resistant Audiences:

Issue: Public school lunches

Claim: Though well intentioned, the Obama-era regulations on public school lunches need to be loosened to lower costs and reduce food waste.

Skeptical or Resistant Audiences:

Issue: Diversity and inclusivity training

Claim: All K-State students should be required to take at least one three-credit-hour course on raising their awareness to diversity and inclusivity.

Skeptical or Resistant Audiences:

Audience-based Reasoning & Assumptions

Again, a powerful component of attempting to persuade skeptical or resistant audiences is that you may be confronting different values, beliefs, attitudes, and worldviews. In order to open your audience for the possibility of persuasion, you may need to target some of these assumptions. In other words, you need to find common ground, the ways in which you and your skeptical audience agree—the values that you hold together.

According to the Toulmin Model, the assumptions—what Toulmin calls “warrants”—are those values or beliefs that serve as a “bridge,” linking the reason and the claim together. Oftentimes, these assumptions are left unstated; that is, readers will accept them because they are commonsensical—they see the link between the claim and the reason to be a natural and reasonable one:

Claim & Reason: I have started knitting to reduce stress because it was suggested to me by my doctor.

Assumption? In this case, the assumption is that personal doctors are a credible source of information regarding health-related concerns. (Hint: Try fitting in substitutes for “my doctor” to identify some assumptions that may not be so reasonable and commonsensical.)

Claim & Reason: Give your nine-year-old child a smart phone because all of their friends already have one.

Assumption? Many readers may not find this argument to be convincing or reasonable because they will not share the assumption, which is that parents should make parenting decisions based upon their children’s friends’ practices.

Claim & Reason: Don’t read American Dirt because its author isn’t Mexican, and she doesn’t know anything about the immigrant experience!

Assumption? As you will discover, complicated arguments may have more than one assumption; that is, different sets of beliefs and values come into play for readers to make sense of the argument. In this case, one prominent assumption may be that books should be valued according to whether they fit the life experiences and social identity of the author. Whether you hold this assumption or not—and many people are divided on this issue—will dictate the degree to which you will accept this claim and reason.

Finally, take a look at this visual argument, in which an activist is protesting mandatory mask policies by holding up this sign, which reads, "My Body, My Choice" and includes this symbol:

Claim & Reason: Governments should not impose mandatory mask policies because mask wearing should be an individual choice.

Assumption? A libertarian, individual-focused belief system links together this claim and reason. According to this belief system, the desires and rights of individuals should be promoted above anything else, even the public good. Many readers would not agree with this position, and they would promote the role of medical science above these libertarian views; in this case, mask wearing is not an individual choice because the spread of diseases such as Covid-19 has consequences for others beyond individuals themselves.

Activity: Unpacking Claims, Reasons, and Assumptions

In the following statements, try to distinguish the claim from the reason. Then, supply the assumption that the audience would need to hold in order for the claim and reason to make sense. If you feel there is more than one assumption, please include those as well.

The movie version of The Reluctant Fundamentalist was awful; it had nothing to do with the book.

Claim:

Reason:

Assumption(s):

I can tell that she is not a very good student because she says nothing in class.

Claim:

Reason:

Assumption(s):

I certainly don’t agree with the alt right, but I just don’t feel comfortable tearing down all those Confederate statues. Aren’t we erasing history when we do that?

Claim:

Reason:

Assumption(s):

The expository writing program should offer more online classes because they are easier to fit into students’ busy schedules.

Claim:

Reason:

Assumption(s):

For these examples, who might represent a skeptical or resistant audience? Would they hold these assumptions? If not, how can the claim and reason be modified to make it more reasonable and convincing for these skeptical readers?

Logos: Claim Types

As you explore your issue, different claims and reasons, as well as tentative skeptical or resistant audiences, consider the rhetorical strategy of “claim types” to help you. It provides you with several different categories to place your own argument. You might find it useful to focus your argument and consider the ways in which you and your skeptical readers differ.

Here is a brief description of the different claim types:

Claims about the reality of your world

Definitional or Categorical: You are arguing that something fits into a particular definition or category.

Star Wars is more than just a science-fiction movie; it is actually a Western.

The debate about gun control really has nothing to do with the constitution.

Resemblance: You are arguing that something is similar to something else.

The Percy Jackson series shares the same motifs and themes as the Harry Potter books.

Millionaire teenage TikTok stars are similar in many ways to gold miners from the nineteenth century: they have made a lot of money, yet with little talent to show for it.

Causal: You are arguing that something will cause something else to happen—which may or may not be beneficial for the audience.

In my opinion, reducing the size of the menu and simplifying the number of ingredients will bring in more customers.

I am going to argue in this presentation that the Harry Potter series helped stimulate interest in reading by diverse young people throughout the first decade of this century.

Claims about policy

Proposal: You are arguing that your readers should do something because it will be good for them and/or will help solve a problem. In this case, you are implying a value judgement about what your audience should do.

As teachers, we should consider making our grading practices more rigorous.

In order to stop the phenomenon of towns dying out in Western Kansas, we should stimulate new growth in organic farming.

Claims about values or judgments

Evaluation or Ethical: You are arguing that something is good (or bad), or, similarly, that it is ethically right (or ethically wrong). Unlike definitional/categorical, resemblance, or causal claims, you are not arguing about the “truth” or “reality” of something; instead, you are implying a judgement, basing your decision of what is “good” or “bad” on criteria that you have assumed to be important.

France has the best cuisine in the world.

Eating meat is wrong.

Activity: Identifying Claim Types

In the list below, figure out the type of each claim:

- Even though many viewers may see it as yet another comic book or Superheroes adaptation, Joker actually fits in the movie genre of the 1970s drama because…

- Eating meat harms the environment because…

- You should become a vegetarian because…

- Not allowing transgender people to use the bathrooms of their gender identity is similar to laws that instituted segregated bathrooms based upon race because…

- Cheerleading is the same as gymnastics because…

- Eating meat is the same thing as abusing animals because…

- Waterboarding is a form of torture because…

- Allowing guns on campus will increase the suicide rate of young men because…

- Guns should not be banned on campus because the right to bear weapons is enshrined in the constitution.

Invention Activity: Using Different Claim Types

One strategy to analyze the logos of your persuasive research essay is to identify the type of claim you are making and then consider other possible claim types. Here is an example based around the issue of cheerleading:

| Definitional: | Cheerleading is a sport because… |

| Resemblance: | Cheerleading is similar to gymnastics because… |

| Causal: | Cheerleading causes body image problems in young women and men. |

| Evaluation:

|

Cheerleading is a good extracurricular activity for young women because… (your reason will be based upon what features makes up a “good extracurricular activity for young women”) |

| Proposal: | Cheerleading should become a recognized college sport because… |

You can use the claim types strategy to clarify audience-based reasons and to consider the differences between your claim and those of your skeptical readers. Looking through these differences may allow you to figure out a point of common ground.

Here is another example based on the issue of whether all expository writing classes should be offered online.

| Your position | Your skeptical reader's position | |

|---|---|---|

| Definitional | Online learning is a type of education. | Online learning is a form of training, not education. |

| Resemblance | For students, taking online expository writing classes is similar to how they use social media. | Online learning is the same as correspondence courses from the 1960s. |

| Causal | Online expository classes will enhance students’ twenty-first- century digital literacy skills. |

Online classes will lead to more plagiarism. |

| Evaluation | Making all expository writing classes online is a good policy for K-State. | Making all expository writing classes online is a bad policy for K- State. |

| Proposal | We should make all expository writing classes go online, | We should reserve expository writing classes only for students who are not local. |

The student writer, when looking at this chart, may be able to consider ways to qualify their argument and make it more persuasive for their skeptical reader. For example, they may concede the importance of establishing teaching policies that offset plagiarism; they may also consider finding common ground in the particular type of students who should be allowed to take these courses and, moreover, the types of classes that may best utilize online learning.

Use a chart like the one below and fill out your own claim types as well as those of a skeptical reader. Then, look for ways to clarify your own position and the common ground.

Your Issue:

| Claim Types | Your position | Your skeptical reader's postion |

|---|---|---|

| Definitional | ||

| Resemblance | ||

| Causal | ||

| Evaluation | ||

| Porposal |

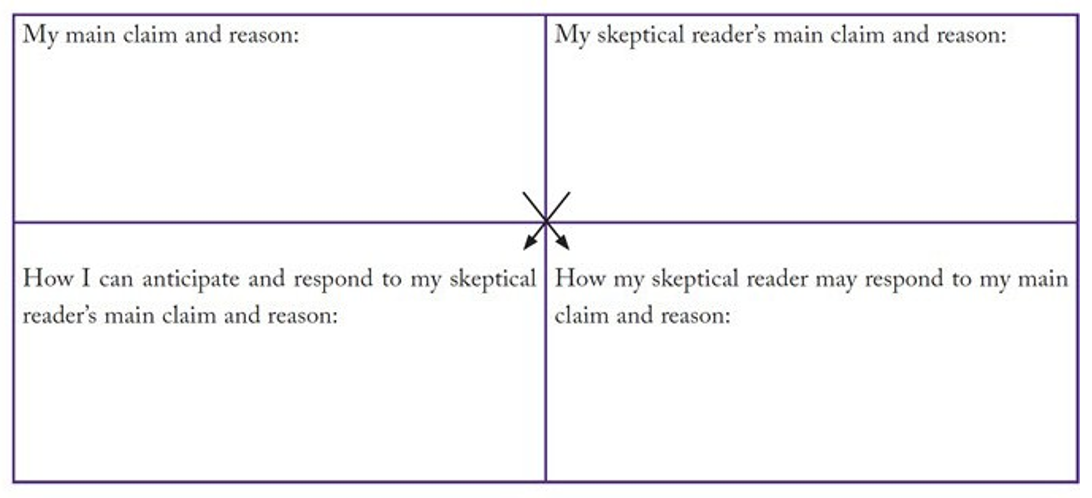

After you have a good grasp on your position and that of your audience, fill out this following table. It may enable you to help create a strategy to write for your skeptical audience and anticipate their concerns.

Dialogical and Invitational Strategies

You have several rhetorical strategies that you can experiment with to craft your message to make sure that your skeptical or resistant readers keep on listening to you and keep themselves open for persuasion. You can think of these strategies as “dialogical,” as many of them ask you to engage your readers as if you are having a dialogue with each other; in this case, you may provide questions, enabling readers to respond and include themselves in the conversation. You can also think of these strategies as “invitational,”[2] as you are inviting your readers to consider the issue with you and trying to find common ground with them. Finally, some researchers may call these approaches “nonthreatening” or “nontraditional,” as you are being empathetic with your readers, trying to understand their point of view and not necessarily trying to win. Overall, you are establishing trust and common ground and attempting to understand what separates your values from those of your audience.

As Carl Rogers suggests, though, these types of dialogical, nonthreatening approaches can be unsettling for writers:

If you really understand another person in this way, if you are willing to enter [their] private world and see the way life appears to [them], without any attempt to make evaluative judgments, you run the risk of being changed yourself. You might see things [their] way; you might find that [they] have influenced your attitudes or your personality.[3]

Remember the challenge of this rhetorical situation: if you hope that your readers will consider changing their mind on the issue, then you as well have to be willing to change and compromise.

In this section, you will encounter several strategies to help you promote this dialogical approach. Here is one example, from the University of Oklahoma, in which the former university president, David Boren, informs his readers, OU students, that he is going to have to raise their tuition. Though only the first six paragraphs have been included, you will be able to detect several strategies Boren uses to connect to his resistant audience.

Dear OU Students:

I am writing to bring you up to date on the status of our University budget and on the recommendations which I will make in regard to tuition to the University of Oklahoma Board of Regents. As a family, I believe that we should have candid and frank discussions of our financial situation.

As you have read, the national recession has forced budget cuts in more than 40 states across the nation this year. Oklahoma is in that number. The Oklahoma state government revenues declined this year by more than $300 million from last year.

The bad news is that to make up for the shortfall the budgets of state agencies have to be cut. The good news is that the governor and the Legislature have placed a priority on support for education and are cutting education even less than other units of state government.

At OU our operating budget has already been cut by about $4 million. In addition to these cuts, we will also have approximately $6 million-$8 million in increased costs which we cannot control. These include items like the rising cost of health care, books and periodicals at the library, and carryover payments for faculty and staff salary increases which took place last year. It is now clear that the Legislature will have no additional funds to help us pay for these added costs. In short, our budget has been hit by a problem in the neighborhood of $10 million-$12 million.

It is also now clear that we cannot solve this financial problem without raising tuition. To try to close the deficit solely with more cuts would harm the quality of education at the University. It would force us to compromise the standard of excellence our students have a right to expect. Even with tuition increases, we will not be able to provide raises for our faculty and staff. All of us will be sharing in the effort to keep up our high standards during this tough budget year.

I have waited as long as I can wait in conscience to make this difficult decision. Other universities in Oklahoma including OSU have already announced increases. I wanted to raise our tuition as little as possible and have been working at the State Capitol to try to find other sources of funds.

What are some of these strategies?

- Boren provides a “buffer”; instead of delivering the bad news about the tuition increase directly, he first builds a rapport with his resistant readers, provides background, and makes it appear that they are a part of this decision-making process.

- Boren delays his main thesis until the fifth paragraph, easing readers into the bad news.

- Boren uses pronouns such as “we” and “our,” emphasizing the fact that he and the students are in this together.

- Boren uses a family analogy, with himself as the father and the students as children that he cares about.

- Boren avoids explicitly stating who is making this tuition increase decision.

As you draft and revise your persuasive research argument, consider the following strategies. They will be organized in three groups:

- Ethos- or Pathos-based Strategies

- Research Strategies

- Organization Strategies

Ethos- or Pathos-Based Strategies

Connect to your readers by building a relationship with them (ethos) or appealing to their emotions (pathos):

- Consider using pronouns, such as “we” and “you,” that help connect you to your readers.

- Flatter your resistant readers and show that you are working hard to understand their side.

- Narrate a vivid story, one that highlights the issue and that appeals to your readers emotionally; in other words, make your readers care about the people in the story and less about their own claims, reasons, and assumptions.

- Make the issue personal for your resistant readers, again possibly through a story or an anecdote.

- Pose questions and show your desire to interact with your readers and get their input.

- Show your humility (another understated type of ethos); share a story of how your thinking on the issue has changed: “I used to feel just like you until…”

- Accurately and fairly summarize your audience’s position and values to show that you respect them.

- Gently show the risks for your audience if they maintain their position.

- Use humor when appropriate; try to get your resistant readers to laugh.

Rhetorical Research Strategies

Rebecca Moore Howard, in her The Citation Project (see http://www.citationproject.net/), reported several concerns about how college student writers used research. For example, students cited material from the first page of their research sources 46% of the time, suggesting that they were not reading these sources carefully and comprehensively. Of their sources, 56% of them were cited only once in their drafts. Furthermore, 52% of the sources involved “patchwriting” in some way—an indication that student writers were paraphrasing and/or quoting these sources in ways that would concern their instructors.

Another concern that students show in their research is their tendency to only choose sources that confirm their ideas and perspectives. In short, these are sources that their skeptical readers may not find persuasive and credible. As a 2014 PEW Research study on political polarization shows, these student writers are acting similar to Americans in general: they prefer to read or view media sources that confirm their worldviews. For example, the PEW study found that 47% of conservative viewers watch a single news source, Fox News.

As this chapter asks you to consider argumentation as taking on risks—after all, you are making yourself vulnerable and allowing for the possibility that your ideas about the issue will change—you should also look for research sources that your own skeptical or resistant readers will find persuasive. In other words, you want to make sure you’re using research rhetorically: with consideration for your audience, message, and persuasive purpose.

We will look at these three strategies for using research rhetorically:

- Consider the credibility and bias of your research sources

- Use different types of research that your skeptical readers will find credible and persuasive

- Shape your research sources to fit your skeptical readers’ assumptions and values

Consider the Credibility and Bias of Your Research Sources

As you choose sources, you’ll want to determine how credible they will be for your readers. Use criteria such as the following to judge how credible your sources are:

- Currency: How recent are your research sources? (Be mindful that certain audiences will expect far more recent research than others.)

- Authority: How easy is it to determine who the author or sponsoring organization is of the source? (If you are using a website, domain names indicated by .gov, .org, or .edu may have more credibility.)

- Comprehensiveness: Does the source include evidence and information that is complete and satisfying for your readers?

- Accuracy: Does the information and evidence in the source appear to be accurate?

In addition to these criteria, you should also be aware of the ideological slant or bias of the source you are considering. You can get an idea about the bias of your sources by going to a website such as AllSides (allsides.com/media-bias), which categorizes many media sites according to a “left” (liberal), center, and “right” (conservative) continuum. For example, the following figure shows how a few well-known media sources are categorized:

| Left | Left-Leaning | Center | Right-Leaning | Right |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Huffington Post

Mother Jones MSNBC The New Yorker The Daily Beast |

The Atlantic

BuzzFeed News The New York Times The Washington Post |

USA Today

Bloomberg Reuters AP |

The Wall Street Journal

The Washington Times |

Breitbart

National Review The New York Post |

Though you don’t necessarily need to stay away from media sources that have an ideological bias—all sources in some way will favor a particular ideology or worldview—you do have to be aware of these ideological and political sources, especially when you are using them for evidence to persuade your own readers.

To get better at examining sources, you might want to develop your strategy of “lateral reading.” Unlike “vertical reading,” in which you literally read closely through a single source, lateral reading asks you to jump to different online media sources to quickly determine what they are saying about the site you are interested in. The author of the online text, Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers, Michael A. Caulfield, describes the process of lateral reading:

When presented with a new site that needs to be evaluated, professional fact-checkers don’t spend much time on the site itself. Instead they get off the page and see what other authoritative sources have said about the site. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the site they’re investigating.[4]

In other words, twenty-first century reading requires intensive and careful reading of sources and, at the same time, scanning of similar sources to figure out how one source fits into a larger network of sources.

For example, imagine you find a source from this organization, the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal (www.jamesgmartin.center)? How will you know if this organization has a strong ideological bias or not? How can you tell if your readers will consider it to be credible?

You can find a little bit about this organization’s political position if you go to its “About Us” page on its website. Here is the statement of the organizational goals:

Our goals are to improve colleges and universities, especially in North Carolina. We want to:

- Increase the diversity of ideas taught, debated, and discussed on campus

- Encourage respect for the institutions that underlie economic prosperity and freedom of action and conscience

- Increase the quality of teaching and students’ commitment to learning so that they graduate with strong literacy and fundamental knowledge

- Encourage cost-effective administration and governance

These are goals that many groups, regardless of ideological conviction, may champion, yet two phrases stand out: “diversity of ideas” and “economic prosperity.” These are concepts that more conservative groups will often be committed to.

By searching about this organization and looking at what other sources say about it, you can begin to get a better portrait of the politics of this organization. You will find that it is linked to the National Review, a traditionally conservative publication, and to the National Association of Scholars, a conservative academic think tank. SourceWatch, a website curated by the Center for Media and Democracy, defines this organization as a “right-wing 501(c)3 nonprofit and associate member of the State Policy Network,” itself a “web of right-wing ‘think tanks’ and tax-exempt organizations.”

Use Different Types of Research That Your Skeptical Readers Will Find Credible and Persuasive

As you conduct library- and Internet-based research, consider the types of research that your audience will value. Although you want to avoid stereotyping your audience, you can make some good educated guesses regarding, for instance, whether your readers will gravitate towards personal stories or towards statistics. Other audiences will be more accepting of information sources such as company blogs, whereas others will expect peer-reviewed academic research articles.

Here is a list of some possible research sources, which is far from complete:

- Primary research sources, including field research, observations, interviews, and surveys

- Peer-reviewed articles from library databases

- Statistics

- Government white papers

- Editorials and commentary

- Human-interest stories or examples from newspaper or Internet sources

- Internet blogs

- Social media sources, including user comments and chat room transcripts

- Personal stories or anecdotes

- Textbooks and class notes

One research strategy, coming from the social sciences, is that of “triangulation”—to find different types of research sources to satisfy your readers. For example, you might find yourself blending several different types of research sources together to enhance your persuasiveness, such as starting off your introduction with a personal story related to the issue, then reviewing alternative perspectives by using library-based research, and then supporting your own position with an interview of a professor, statistics that come from a textbook, and a statement from a company press release.

Shape Your Research Sources to Fit Your Skeptical Readers’ Assumptions and Values

Your research will take on several different purposes. Among many possibilities, it will

- Support your main reasons

- Support your assumptions

- Show your understanding of alternative perspectives

- Reach your audience emotionally

- Emphasize strengths in your argument and subordinate weaknesses

- Rebut the reasons, assumptions, or evidence of alternative or oppositional sources

- Provide an example of the issue

- Demonstrate your commitment to the issue

You should use readerly cues and explain your use of the research to help guide your readers and shape their reading experience. (If you look up “Transitional Devices” on the Purdue Online Writing Lab, you’ll find a substantial list of these readerly cues.) In fact, rhetorically researching and using research rhetorically implies that you are thinking about your readers and how they will be interacting with the information, and, hopefully, being persuaded by how you are using the research.

Here is one example of how Kelsey Reith uses research rhetorically in her essay, “Bathroom (In)Security” (please see the Student Example in the back of this chapter):

Next, safety is not only a concern for those that would support the strict sex- assignment use of public restrooms; safety is a huge issue for the transgender community. Imagine a woman, who would for all intents and purposes appears to be woman, but perhaps her birth certificate says otherwise. What might happen to her if she were to follow her sex-assignment, and walk into the men’s bathroom? This is the reason that harassment is frequently reported by the transgender community. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey found that in the past year 59% of those surveyed had avoided the bathroom out of fear of conflict, 12% had been verbally harassed, and 1% had been physically and sexually harassed while using public restrooms (Barnett). The way transgender people are politically and socially treated in bathrooms is an issue of discrimination. This treatment has been shown in several studies to lead to violence, poverty, and isolation. Which puts transgender people’s quality of life at risk. Between 2003 and 2016, there has only been 1 case of a transgender individual committing sexual assault in a public restroom, while there have been 19 cases of cis-gender men pretending to be transgender in order to enter women’s bathrooms and commit sexual assault. There has been no evidence to suggest a connection between laws that permit transgender people to use their preferred bathrooms and an increase in cases of assault by cis-gender men disguised as transgender women (Barnett). What this means is that predators have been committing sexual assault under the guise of the transgender identity for a significant time and there hasn’t been a rise of these occurrences in areas where restroom facility policy is favorable to the transgender community. When it comes to sexual assault in bathroom, laws that allow transgender people to use their preferred restroom are not the problem, and not allowing them to do so is not the solution to the behavior of cis-gender predators.

Importantly, although Reith is only using one research source here, she is paraphrasing the statistics from this source and introducing, contextualizing, and explaining her use of the sources (the chunks that have been underlined). She asks her readers interactive questions, and she explicitly tells them what the research is doing or showing:

- “This treatment has been shown in several studies to lead to violence, poverty, and isolation.”

- “What this means is that predators have been committing sexual assault under the guise of the transgender identity for a significant time…”

Finally, shaping your research sources might also entail having to explain or qualify your use of them. For example, what should you do if you have found the “perfect research source,” yet it’s one that you are fearful will not meet the ideological worldview of your readers? In this case, instead of hiding the ideological angle of the source, admit it and then qualify your use of the source:

- Although the United States Interior Secretary David Bernhardt is well connected to the petroleum industry, we shouldn’t immediately discount his rejection of environmental regulations.

- Undoubtedly, many conservative readers will wonder why I have cited statistics from a study that PETA sponsored. Although, like you, I do not accept some of the advocacy work that PETA does, I think we can all agree that dangerous conditions of farm animals need to be looked at—to increase the safety of meat consumers and relieve the suffering of animals.

Organizational Strategies

Importantly, your organizational decisions—the order in which you arrange your reasons as well as those that represent the alternative positions—are powerful ways to interact with your readers.

A "traditional" or classical approach to organization tends to include an introduction in which you identify the issue and explicitly state your main claim and reasons; the body of the essay in which you summarize the major alternative or oppositional positions and then attempt to rebut or concede them, providing your own reasons and support; and finally, a conclusion in which you restate your main claim and reasons. However, we encourage you to use a delayed-thesis or dialogic approach to this assignment, as it tends to reduce threat in your resistant or skeptical reader. However, you if you choose a more traditional organizational approach, you’ll need to be very mindful that your explicit claim, so early in the argument, is likely to make your skeptical readers even more resistant and defensive. You will want to use some of the strategies from this chapter to invite these readers to understand your own views and values.

Delayed-Thesis Approach

One way around highlighting your position early on in your persuasive research essay—and, consequently, running the risk of losing your audience at the start—is to delay your claim until later in the essay. Like the dialogic approach that we will explore next, you can show sympathy towards your readers’ views, create common ground, and use questions or other strategies before then contributing your own position on the argument. Hopefully, by that point, you will have created a good relationship with your readers, and they will be more willing to listen to your side.

The Dialogic Approach

The dialogic approach to multisided arguments draws attention to the give-and-take nature of discussions on complex topics. It is similar to the psychological therapy models developed by Carl Rogers, who emphasized value-neutral conversations and empathic listening to understand alternative or opposing ideas. In other words, as the writer, you do not pass judgments on your readers’ views—especially if they are different than yours; instead, you demonstrate that you are listening to your readers’ perspectives, values, and concerns. Your main aim is to build common ground between you and your readers with the ultimate goal that you are going to lower their resistance and open themselves up to persuasion.

Those using this strategy take pains to illustrate that they understand the varied positions on a topic and have considered others’ perspectives. Writers will use the delayed-thesis approach, as it allows the writer to connect to their resistant readers before acknowledging their own position. Dialogic argument approaches commonly follow this outline:

Introduction

Dialogic Discussion

Delayed Thesis and Support

Conclusion

Maxine Hairston[5] offers another way of organizing dialogic arguments:

- An introduction that fairly, honestly, and objectively identifies the issue.

- An explanation of the positions that oppose that of the writer. In this section, the writer is demonstrating they understand the alternative positions and the values and beliefs of skeptical or resistant readers.

- An explanation of the position that the writer holds.

- An attempt to clarify the common ground between the writer’s position and the alternative positions. For example, what are the key beliefs or assumptions that the writer shares with their skeptical readers?

- An attempt to find a way to resolve the issue that attempts at a compromise between the writer’s position and those of their skeptical readers.

Note: A challenge of the dialogical approach is that because it undercuts the differences between the writer and alternative or oppositional perspectives, many writers end up writing exploratory, informative, or non-persuasive texts. If you choose this approach, you should still acknowledge that you do hold a position on the issue, even though you are attempting to build common ground and maintain a good rapport with your readers.

![]()

Drafting Activities

Summarizing Your Audience’s Views

Using the summarizing skills we’ve been practicing, write a fair and objective summary of your reader’s views on the topic you’ve chosen. You’ll want to think here about what it means to write a general summary over a larger topic rather than a specific summary over one text: What is the main problem behind your issue? What is your audience’s stance on that problem?

Remember, you need to summarize the reader’s views in a way that your resistant audience would read it and say “yes, that’s what I believe.” You’ll also need to maintain a respectful and professional tone.

Establishing the Conversation

Once you feel as though you have a clear sense of the overall conversation, as well as the views of your resistant reader, you can begin drafting the early parts of your research essay where you explain the issue more broadly as well as the multiple viewpoints present in response to the topic. Remember, for this essay we’re asking you to experiment with a delayed-thesis argument. That means that your thesis statement—your own position—will not be located at the beginning of the essay. Instead, it’s likely to be either near the middle of the essay (if you’re using a version of a dialogic argument structure) or closer to the end of the essay, if you’re using a more traditionally delayed-thesis structure.

As you think about drafting the earlier parts of your essay, then, you might find that it looks somewhat different than the kinds of research essays you’ve been asked to do in the past. You’ll find an organizational plan for both a delayed-thesis argument and a dialogic argument in the Organizational Strategies section above. These plans can help you structure your research essay in a way that will be most effective for your resistant/skeptical audience.

In each case, you’ll notice that the first few paragraphs of your essay will focus on establishing the broader context for the topic itself and summarizing other viewpoints. With that in mind, and given what you now know from your research about the topic and about alternative viewpoints on this issue, begin drafting the early parts of your essay. How do you want to establish the conversation? What kind of context for the issue is immediately required for your reader?

Your instructor might then ask you to share these drafts with your peers, checking for objectivity and accuracy in the summaries, clarity and thoroughness of establishing the conversation, professional and respectful tone, and overall purpose and structure.

What Is Your Position?

By this stage of the writing process, you should be well on your way to a thorough understanding of your issue; you have written a complete summary of your audience’s perspective on the topic, and you’ve begun to establish the larger conversation around the issue. You should have read a lot of credible sources about your topic and considered multiple viewpoints. You’re now likely ready to begin building your own claim.

Consider the ways that your thinking on the issue has changed as you have research and have analyzed your resistant audience. Then, freewrite your own stance or position on the issue; eventually, this will become the main claim that you will offer to your readers.

Here are a few examples that appear in the student examples at the end of this chapter:

- I understand why one might feel that letting transgender people use the bathroom of their gender identity would create more problems than solutions. Nonetheless, I have to disagree with this stance. I believe transgender people should be able to use which ever bathroom they feel best reflects their gender identity. For me the issues of human rights, safety, and the evolution of bathroom policies make it clear how the transgender community should be treated when it comes to public facilities. (Kelsey Reith, "Bathroom (In)Security")

- It is important to recognize that the moral concerns about encouraging drug use, as well as the safety concerns of needle-stick accidents and increased crime rates are valid. However, Needle Exchange Programs are used because they have benefits as well. While critics and proponents of NEPs disagree on whether or not they should be used, both groups are concerned with the safety and health of their communities. (MacKenzie Gwinner, "Should the U.S. Use Needle Exchange Programs?")

- I am excited about these initiatives and am eager to see what the planning groups develop. I am writing, however, to propose that the overall Visionary Plan could be strengthened and that present financial and enrollment challenges could better be addressed by drawing these initiatives together with a common purpose that is aligned with K-State’s mission, vision, and values: addressing climate change. (Sarah Inskeep, "Sustainability & K-State: A Letter to President Myers")

In each of these three claims, you will find that they start from the perspectives of their resistant audience and then shift to the position of the writer.

Connecting Your Position to Your Audience

To help you plan and develop the audience-based reasons that will make your persuasive research essay effective, use this activity to test whether your reasons, assumptions, and research will be persuasive for your intended resistant/skeptical audience (and repeat for as many reasons as you have):

Claim:

Reason:

Evidence or research to support the reason:

What type of source would have this information?

Assumption(s):

Which assumptions might the audience resist?

Evidence or research needed to support resisted assumptions: What types of sources would have this information?

Outlining & Freewriting Opportunities

As you continue drafting your persuasive argument, experiment with several of these outlining and freewriting strategies. Because of the sophistication and complexity of the persuasive research argument, you'll want to break it down into distinct drafting opportunities or sections.

Outlining

Consider these following organizational components below and create a more specific outline for your argument to help guide you and break up your drafting goals. You'll need to think about where you are going to place your main claim—without challenging your resistant readers too early—how you are going to deal with your readers' opposing views, and in what order you are going to organize your own reasons that support your main claim. Here are some generic organizational components you can use:

- Introducing your issue

- Inviting your audience to the conversation

- Summarizing opposing views

- Countering or conceding to opposing views

- Establishing your main clam

- Finding common ground with your resistant readers

- Supporting your main reasons

- Concluding your argument

Freewriting

Use several of these following questions to help you generate more ideas. When you are finished, you will want to go back, reread, and then revise and shape these early freewrites.

Establishing the Conversation

- What are the most important positions that make up this issue?

- Why do people care about this issue? How is it significant for the public?

- Why do people disagree about this issue? What is at the heart of this disagreement?

Resistant Readers' Perspectives

- What is your resistant readers' most persuasive reason? Why is it persuasive or challenging for you? How will your rebut or concede this point?

Common Ground

- At the heart of the issue, with what do you and your audience both agree?

Your Claim & Reason

- What is your most important reason? Why? How will your readers react to this reason? To what extent will this main claim and reason satisfy their beliefs, assumptions, and values?

- What specific research, personal experience, examples, statistics, expert testimonies, and other types of evidence will your audience find the most compelling? Why?

Your Conclusion

- What main idea do you want to leave your readers with? How do you want to make them feel?

- What is the "bigger picture" of your argument? What other larger issues or concerns can you connect your audience to?

- How can you reaffirm your common ground and your positive relationship with your resistant readers?

Revision: Avoiding Dropped-In Quotations

A common usage concern in papers that use the outside voices of secondary sources is the “dropped-in quotation,” sometimes called a “dropped quote,” in which the quotation is inserted into the paragraph without enough of an introduction or context. Readers will find the quotation to be too abrupt, and, additionally, they will require more explanation to understand why the quotation is being used. Readers will also be worried that the secondary voice of the quotation is dominating the paragraph—doing the work that the writer should be doing.

Here is an example of a dropped-in quotation:

Another reason that Manhattan High School should develop a vaping awareness program for students is because vaping companies have been directly marketing teenagers. “As recently as 2017, as evidence grew that high school students were flocking to its sleek devices and flavored nicotine pods, the company refused to sign a pledge not to market to teenagers as part of a lawsuit settlement” (Cresswell and Kaplan). Companies like Juul should not be allowed to market directly to high-school students.

To avoid the dropped-in quotation usage problem, experiment with these strategies:

Introduce the quotation

In the underlined passage below, the writer has provided some more context and directly introduced the quotation:

Another reason that Manhattan High School should develop a vaping awareness program for students is because vaping companies have been directly marketing teenagers. For example, one company that has attracted a lot of attention has been Juul, which has been marketing to teenagers for several years. According to a New York Times article, “As recently as 2017, as evidence grew that high school students were flocking to its sleek devices and flavored nicotine pods, the company refused to sign a pledge not to market to teenagers as part of a lawsuit settlement” (Cresswell and Kaplan). Companies like Juul should not be allowed to market directly to high-school students.

After the quotation, provide a summary or explanation in your own words

This strategy further develops the use of the quotation, emphasizing to readers why the quotation was used and how it meets the persuasive goals of the writer.

Another reason that Manhattan High School should develop a vaping awareness program for students is because vaping companies have been directly marketing teenagers. For example, one company that has attracted a lot of attention has been Juul, which has been marketing to teenagers for several years. According to a New York Times article, “As recently as 2017, as evidence grew that high school students were flocking to its sleek devices and flavored nicotine pods, the company refused to sign a pledge not to market to teenagers as part of a lawsuit settlement” (Cresswell and Kaplan). In other words, Juul has not been doing what cigarette companies have been doing for decades. Juul has not been telling young consumers the health risks associated with vaping. Companies like Juul should not be allowed to market directly to high-school students.

Tell your reader why you used the quotation or why the quotation is important

Similarly, this strategy asks you to directly respond to the “So What?” question. Why did the writer actually decide to use this quotation?

Another reason that Manhattan High School should develop a vaping awareness program for students is because vaping companies have been directly marketing teenagers. For example, one company that has attracted a lot of attention has been Juul, which has been marketing to teenagers for several years. According to a New York Times article, “As recently as 2017, as evidence grew that high school students were flocking to its sleek devices and flavored nicotine pods, the company refused to sign a pledge not to market to teenagers as part of a lawsuit settlement” (Cresswell and Kaplan). In other words, Juul has not been doing what cigarette companies have been doing for decades. Juul has not been telling young consumers the health risks associated with vaping. This quotation shows that Juul’s main marketing strategy has been to market to young consumers. Companies like Juul should not be allowed to market directly to high-school students.

Shift the quotation to a paraphrase and/or use a fragment of the quotation in your paraphrase

A final strategy asks writers to decide whether they actually need the full quotation; they may opt instead for a paraphrase, which they cite, or for a fragment of the quotation. The benefit of this approach is that it allows writers to more smoothly connect their position to that of the secondary source.

Another reason that Manhattan High School should develop a vaping awareness program for students is because vaping companies have been directly marketing teenagers. For example, one company that has attracted a lot of attention has been Juul, which has been marketing to teenagers for several years. According to a New York Times article, from 2017, lawmakers have learned that high school teenagers have been attracted by Juul’s “sleek devices and flavored nicotine pods,” but Juul refused to acknowledge the importance of teenage consumers in its overall marketing plan (Cresswell and Kaplan). In other words, Juul has not been doing what cigarette companies have been doing for decades. Juul has not been telling young consumers the health risks associated with vaping. In fact, as Cresswell and Kaplan have pointed out, Juul’s main marketing strategy has been to market to young consumers. Companies like Juul should not be allowed to market directly to high-school students.

Workshop Option #1: Peer Review

Use these workshop questions to evaluate your own persuasive research argument or a classmate’s argument:

Focus/Purpose

- Where has the writer clearly identified the topic/issue/problem? How do they explain why that topic is controversial and timely?

- Who is the resistant audience? What does the writer do to engage that audience with their argument?

Development

- What are the various perspectives on the issue? Does the writer represent those perspectives fairly?

- Where does the writer invite the audience to consider with them other viewpoints?

- How well does the writer integrate research sources and explain how that evidence supports their overall claim?

Organization

- Is the writer using a delayed-thesis or Rogerian organizational structure in order to best persuade the resistant audience? Which structure does the writer seem to be using? Is it effective?

- Is the presentation of the argument consistent with its thesis and general organizational approach?

- Where does the writer utilize topic sentences, transitions, and/or other writing choices that help guide the reader from one idea to the next (both within individual paragraphs and within the essay as a whole)? Where are these necessary “signposts” missing in the draft?

Tone/Style (and Focus)

- Evaluate the essay’s overall rhetorical effect by assessing its use of logos, pathos, ethos, and kairos.

- What is that overall effect and what comments/suggestions would you offer the writer to strengthen how those appeals work for the resistant audience?

Workshop Option #2: Peer Review Using Role Play

For this workshop, work in small groups and take on one or more of these following workshop roles. Each role will be responsible for examining a different aspect of your classmate’s persuasive research essay draft. Make sure you jot down useful notes for your classmate.

1. Controversy Pulse Checker and Opposing View Finder

Make sure that the writer has actually chosen a multisided controversial issue that’s manageable for this assignment’s length. If the topic seems more informative than persuasive, or too broad, alert the writer and brainstorm ways to create a more controversial or tighter claim.

Also, make sure the writer has summarized the possible alternative/opposing views and then rebutted those views to strengthen their argument.

2. Significance and Source-Control Detector

Look for the significance of the issue, the “so what?” factor: why is this topic important for the writer, the public, or the audience? If the significance is not clear throughout the essay, ask the writer why they are invested in the issue and why it is an important one for the audience.

Check, too, that the writer is not simply stringing sources together. Point out places where the writer does not integrate, or loses control of, their sources. Note places, too, where the writer is making clear and explicit connections between points and sources.

3. Claim Confirmer and Support Supporter

Underline the sentence(s) that provide(s) the writer’s claim. If you cannot find a clear claim, let the writer know that they need to be more explicit. (Remember, the claim is likely to come in the middle or at the end of the essay).

Additionally, examine the writer’s “because” reasons that support the claim. Each of these reasons should be developed by specific examples and other types of evidence and explanation. If there is little support, indicate the places where more support and explanation is needed.

4. Audience Analyzer and Organizational Engineer