2 Chapter 2: Critically Reflecting on Student Biographies

Critically Reflecting on Student Biographies

Across the United States, the tapestry of the K-12 student population has changed dramatically over the last twenty years and is continuing to evolve. For example, today, one in four children in the United States arrives at school from an immigrant family and live in households where a language other than English is spoken at home (Samson & Collins, 2012). As a future teacher, it is important to think about the student population you will be working with in your classroom. This chapter will explore key issues related to getting to know your students biographies. This exploration of student biographies begins with an understanding of our own Autobiographical Narratives. We will build on our Autobiographical Narratives by learning more about ourselves as learners and how our own learning styles might influence our future instructional practices. Finally, this chapter will explore how our sociocultural background or “knapsack” influences our perceptions.

Section I: Autobiographical narratives

2.1 Essential Questions

At the end of Section I, the following questions should be answered:

- What is an Autobiographical Narrative?

- What is the role of an Autobiographical Narrative in the classroom?

- What information is most important to include in an Autobiographical Narrative? Why?

- How might you adapt Autobiographical Narratives if you wanted to apply them with K-12 students?

- What did you learn about your peers as a result of sharing your Autobiographical Narratives with each other?

Autobiographcial Narratives

Every student brings unique talents and skills to the classroom. As educators, it is our job to find out what these talents are so that we can build upon them within the classroom. According to Herrera (2016), “understanding the core aspects of each student is essential to the process of identifying the skills and knowledge that he or she brings to the classroom” (p. 7). Autobiographical narratives are one of the key tools that educators can use to learn about the core aspects of each individual student biography.

Autobiographical narratives pull from research on Biography Driven Instruction (BDI). Biography-Driven Instruction (Herrera, 2016) is a communicative method of teaching and learning the helps teachers understand and maximize assets of the student biography to provide a more culturally responsive approach to teaching. For more information on BDI, please read the following article titled: Approximating Cultural Responsiveness: Teacher Readiness for Accommodative, Biography-Driven Instruction.

2.2 A Closer Look

The following article provides an in depth look at the following four key dimensions of Biography-Driven Instruction: sociocultural, linguistic, academic and cognitive. As you read the article, please consider the following questions:

- How does CRTP promote an asset-based perspective on teaching and learning?

- What is the purpose of each of the following phases of BDI: activation phase, connection phase, and affirmation phase?

- Which level of the ARS do you think is most important? Why?

- Which of the five themes in participants’ perceptions of BDI processes and outcomes did you find most powerful? Why?

Approximating Cultural Responsiveness: Teacher Readiness for Accommodative, Biography-Driven Instruction [https]

Creating Autobiographical Narratives

When creating autobiographical narratives, it is essential to consider the student population for whom you wish to apply the narratives as this will largely influence the design of your narrative. For example, students at the Kindergarten level will need a much different autobiographical narrative than students in 12th grade. In addition, you will want to think about how much information you would like to gather directly from the students. Depending on the age, needs, and even language proficiency levels of your students, some autobiographical narratives can be added to/completed by parents or primary caregivers.

Once you have established these basic parameters, you will want to determine what information you would like to gather. This information can range from very general to very specific. A good recommendation is that you try to gather information about each of the following four dimensions of the students biography:

- Sociocultural (SC)

- Who are the people in their family?

- Where were they born?

- Where were they raised?

- Who are the most important people in their lives?

- Linguistic (LG)

- What is their first language?

- What is their second language?

- What do they consider their strengths/weaknesses to be when it comes to language?

- Academic (AC)

- Where did they go to school?

- What special programs were they involved in at school?

- Did they participate in any sports?

- What did they like most/least about school?

- Cognitive (COG)

- What is the students learning style?

- What do they consider their strengths when it comes to learning?

- What do they struggle with when it comes to studying?

As part of this course, you are going to be asked to complete your own Autobiographical Narrative. When creating your Autobiographical Narrative, please keep these four dimensions in mind. Each dimension plays a critical role in defining who you are as an individual and future teacher.

I have included a sample of my Autobiographical Narrative below. You will also find a link to this narrative in the Module tab titled: Meet your Professor and GradCats: Autobiographical Narratives.

2.3 An Example in Practice

Applying Autobiographical Narratives

Using insights gleaned from students autobiographical narratives, teachers have the knowledge they need to make critical adaptations to their instructional practices to better meet the needs of their student populations. A few of these adaptations have been identified below based on the potential information that could have been learned about the four dimensions of the student biography.

- Sociocultural (SC)

- Invite family members in to share information about their cultural background.

- Ask a family member to share expertise related to their professional practices.

- Have the student share information about another city, state, or country they may have lived in and/or traveled to at some point in their lives.

- Linguistic (LG)

- Have students use their first language to promote development/transfer as they acquire English.

- Provide specific interventions for students to help them address areas where they may be struggling.

- Capitalize on students “strengths” and make them language models for the class.

- Academic (AC)

- Build on prior academic experiences to support new learning in the classroom.

- Promote active engagement in school activities, sports, and/or other programs.

- Cognitive (COG)

- Incorporate multiple learning styles.

- Provide learning strategies to support students in and outside the classroom setting.

These are just a few ways you can apply the information learned from autobiographical narratives in the classroom.

Individually brainstorms some additional ways you might use the information from autobiographical narratives done with students in the classroom. Write down at least three ideas down on a separate sheet of paper.

Section II: Multiple Intelligences

2.4 Essential Questions

At the end of Section II, the following questions should be answered:

- What are the multiple intelligences?

- How did they evolve?

- What are my intelligences?

- Why are they important to know?

- How does knowing my intelligences impact me as a future teacher?

Multiple Intelligences

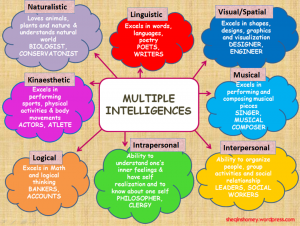

The theory of multiple intelligences was developed in 1983 by Dr. Howard Gardner, professor of education at Harvard University. The theory suggests that the traditional notion of intelligence, based on I.Q. testing, is far too limited. Instead, Dr. Gardner proposed eight different intelligences to account for a broader range of human potential in children and adults. These intelligences are:

- Linguistic intelligence (“word smart”)

- Logical-mathematical intelligence (“number/reasoning smart)

- Spatial intelligence (“picture smart”)

- Bodily-Kinesthetic intelligence (“body smart”)

- Musical intelligence (“music smart”)

- Interpersonal intelligence (“people smart”)

- Intrapersonal intelligence (“self smart”)

- Naturalist intelligence (“nature smart”)

Dr. Gardner did not randomly identify these intelligences. He established the following criteria for identification of each unique intelligence:

- It should be seen in relative isolation in prodigies, autistic savants, stroke victims or other exceptional populations. In other words, certain individuals should demonstrate particularly high or low levels of a particular capacity in contrast to other capacities.

- It should have a distinct neural representation—that is, its neural structure and functioning should be distinguishable from that of other major human faculties.

- It should have a distinct developmental trajectory. That is, different intelligences should develop at different rates, and along paths which are distinctive.

- It should have some basis in evolutionary biology. In other words, an intelligence ought to have a previous instantiation in primate or other species and putative survival value.

- It should be susceptible to capture in symbol systems, of the sort used in formal or informal education.

- It should be supported by evidence from psychometric tests of intelligence.

- It should be distinguishable from other intelligences through experimental psychological tasks.

- It should demonstrate a core, information-processing system. That is, there should be identifiable mental processes that handle information related to each intelligence. (Gardner 1983; Kornhaber, Fierros, & Veneema, 2004)

2.5 A Closer Look

The following video, by Howard Gardner himself, describes the Multiple Intelligences in more depth. As you watch the video, use the following questions to consider as a guide.

- What are three insights you gained from watching this video on Multiple Intelligences?

- What are two benefits of using Multiple Intelligences in classrooms?

- Did any of your previous teachers use Multiple Intelligences when planning/delivering classroom instruction?

- What is one question I still have about the Multiple Intelligences?

Take a moment to respond to the questions you were asked to think about before watching the video. Based on your responses, how has your knowledge of the multiple intelligences grown? How might you apply this information as a future teacher?

The importance of multiple intelligences

According to research by Dr. Gardner (Gardner, 1983), our schools and culture focus most of their attention on linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligence. We esteem the highly articulate or logical people of our culture. However, we should also value individuals who have gifts in the other intelligences: the artists, architects, musicians, naturalists, designers, dancers, therapists, entrepreneurs, and others who enrich the world in which we live.

Unfortunately, many children who have these gifts do not receive reinforcement for them in school. In fact, many of these kids may end up being labeled “learning disabled,” “ADHD” (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), or simply underachievers, when their unique ways of thinking and learning aren’t addressed in the classroom. The theory of multiple intelligences proposes a major transformation in the way our schools are run. It suggests that teachers be trained to present their lessons in a wide variety of ways using music, cooperative learning, art activities, role play, multimedia, field trips, inner reflection, and much more.

This is what makes the theory of multiple intelligences so important! In fact, it has grabbed the attention of educators around the country since it was introduced by Dr. Gardner. Currently, hundreds of schools are using its philosophy to redesign the way it educates children.

2.6 Example in Practice

- What do the educators share about the impact of integrating MI (first video)?

- How do students see themselves as learners when teachers tap into their multiple intelligences (first video)?

- Which character are you most like in the land of Oz (second video)?

Unfortunately, there are still thousands of schools still out there that teach the same old way, through lectures, worksheets and textbooks. The challenge is to get this information out to many more teachers, school administrators, and others who work with children, so that each child has the opportunity to learn in ways that are harmonious with their mind.

The theory of multiple intelligences also has strong implications for adult learning and development. Many adults find themselves in jobs that do not make optimal use of their most highly developed intelligences (for example, the highly bodily-kinesthetic individual who is stuck in a linguistic or logical desk-job when he or she would be much happier in a job where they could move around, such as a recreational leader, a forest ranger, or physical therapist). The theory of multiple intelligences gives adults a whole new way to look at their lives.

What are my intelligences?

One of the most remarkable features of the theory of multiple intelligences is how it provides eight different potential pathways to learning. If a teacher is having difficulty reaching a student in the more traditional linguistic or logical ways of instruction, the theory of multiple intelligences suggests several other ways in which the material might be presented to facilitate effective learning. Whether you are a kindergarten teacher, a graduate school instructor, or an adult learner seeking better ways of pursuing self-study on any subject of interest, the same basic guidelines apply. Whatever you are teaching or learning, see how you might best connect with it:

- Words (linguistic intelligence)

- Numbers or logic (logical-mathematical intelligence)

- Pictures (spatial intelligence)

- Music (musical intelligence)

- Self-reflection (intrapersonal intelligence)

- Physical experience (bodily-kinesthetic intelligence)

- Social experience (interpersonal intelligence), and/or

- Experience in the natural world. (naturalist intelligence)

2.7 A Closer Look

So the question now is, what type of intelligence are you? To find out the answer to this question, you are going to take a brief survey. Before taking the survey, write down the three intelligences you think you use most as a learner (rank them in order from strongest to weakest).

Now, take the Multiple Intelligences Survey located at the following link: http://literacyworks.org/mi/assessment/findyourstrengths.html

- What was your top intelligence based on the survey?

- What you top intelligence the same as you thought it was? If not, what did you think it was?

- What implications can you draw from your results?

- Why do you think it is so important to know what your intelligences are as a learner?

- How might this affect you as a future teacher?

Professional implications

The theory of multiple intelligences is so intriguing because it expands our horizon of available teaching/learning tools beyond the conventional linguistic and logical methods used in most schools (e.g. lecture, textbooks, writing assignments, formulas, etc.). One research study done by a third grade teacher, Bruce Campbell (1991), found the following positive outcomes as a result of creating and implementing multiple intelligences in his classroom:

- The students displayed increased independence, responsibility and self direction over the course of the year.

- Students previously identified as having behavioral problems made significant improvement in their behavior.

- Cooperative skills improved in all students.

- Ability to work multimodally in student presentations increased throughout the school year with students using a minimum of three to five intelligence areas in their classroom reports.

- The more kinesthetic students particularly benefited from the active process of moving from center to center every fifteen to twenty minutes.

- Leadership skills emerged in most students. Several students who had not previously displayed leadership abilities took the lead with their groups in the Music Center, the Building Center, the Art Center and particularly in the Working Together Center.

- Parents reported frequently that behavior improved at home, more positive attitudes about school were exhibited, and attendance was increased.

- Daily work with music and movement in content areas helped students retain information. At the end of the year, all students were able to remember several songs created as early as September which contained specific academic information.

- The role of the teacher changed as the year progressed, becoming less directive and more facilitative, more diversified, less of a taskmaster and more of a resource person and guide.

- Students become progressively more skilled at working effectively in this unique and non-traditional classroom format (Cambell, 1991).

Do you think you would find similar outcomes to Mr. Campbell if you created and implemented a Multiple Intelligence classroom? Why or why not?

“Individually brainstorms additional benefits you see in implementing multiple intelligences in the classroom. Think about the specific grade level(s) you plan on working with as you brain storm your list. Write down at least three specific benefits on a separate sheet of paper.

Section III: Unpacking our Knapsack

2.8 Essential Questions

At the end of Section III, the following questions should be answered:

- What is in your knapsack?

- How has your “privilege” influenced you personally?

- Why it is important to understand the concepts of oppression and privilege and how they affect our lives?

- In what ways might these concepts influence our future teaching?

As children, many of us may think at one point in our lives: I am never going to be like my mother or father when I grow up! Then, as adults, we find ourselves doing or saying things exactly like our mother or father! These acquired behaviors are subconsciously learned as part of the environment in which we are raised. Although we may not want to mimic the behaviors of our primary caregivers, they are subconsciously learned. This does not mean that we can not unlearn these behaviors, change them, or maintain them if we choose. The key is to be aware of these behaviors and the impact they may have on us both personally and professionally.

Unpacking your knapsack

Most commonly, inequalities in the United States have been explored and have been taught from the perspective of those who are victimized by inequalities. Studies of racism, sexism, classism, discrimination based on sexual orientation, and other forms of discrimination have focused mainly on oppression and on those who are oppressed. However, critical whiteness studies and other disciplines have begun to include the concept of privilege in the discussion in order to create a more thorough analysis of the dynamics of systemic inequality.

One of the most powerful explorations of white privilege is linked to the work of Dr. Peggy McIntosh. As a women’s-studies scholar at Wellesley in 1988, McIntosh wrote a paper called “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies” (Rothman, 2014). This was followed up a year later with her article titled: White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.

2.9 A Closer Look

In order to understand this concept of privilege and its implications for you personally as well as professionally, please read the article below. Please pay special attention to the “Some Notes for Facilitators on Presenting My White Privilege Papers” at the end of the article.

White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack [pdf]

After reading the article, watch the following TED Talk featuring Peggy McIntosh. As you watch the video and reflect on the article, use the following “Questions to Consider” as a guide.

- What impact has white privilege had on my life?

- What impact might white privilege have on the lives of my future students?

- How might white privilege influence my future work environment/colleagues?

- In what ways might I address white privilege in the future?

Dr. McIntosh currently works at Wellesley, where she is the founder and associate director of the SEED (Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity) Project. She work focuses on educating teachers and professors about white privilege in order to make school curricula more “gender fair, multiculturally equitable, socioeconomically aware, and globally informed” (Rothman, 2014).

Conclusion

This chapter has explored autobiographical narratives, multiple intelligences, and the importance of understanding privilege. As you leave this chapter, please think about what you have learned and how you will apply it to your future professional practice. Hopefully you have some new tools in your tool kit to learn about your students backgrounds with autobiographical narratives. In addition, you should have some new tools in your teacher tool kit when it comes to teaching to your students multiple intelligences. Finally, you should have gained some new insights about your own personal beliefs and privilege. Know about these will serve you well when working with students in the classroom!

References

Campbell, B. (1991). Multiple intelligences in the classroom. The Learning Revolution. https://www.context.org/iclib/ic27/campbell/

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

Herrera, S. (2016). Biography-driven culturally responsive teaching (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Kornhaber, M., Fierros, E., & Veenema, S. (2004). Multiple intelligences: Best ideas from research and practice. Pearson.

Rothman, J. (2014). The origins of “privilege.” The New Yorker.

Samson, J.F., & Collins, B.A. (2012). Preparing all teachers to meet the needs of English language learners: Applying research to policy and practice for teacher effectiveness. Center for American Progress. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED535608.pdf

Media Attributions

- Brainstorm lg © Epic Top 10

- Howard Gardner © Leonardo Pervi

- Multiple Intelligence Photo © badudetsmedial