3 Understanding Cues, Behaviors, and Dysregulation

Dr. Erin Hambrick; Dr. Jessica Lane; and Dr. Rebeca Chow

Trauma comes back as a reaction,

not a memory.

– Bessel Van Der Kolk

Dr. Gaskill: Attachment and Dysregulation

When children or teens have been exposed to prolonged experiences of unpredictable stress, including potentially traumatic experiences, the lower, more primitive parts of the brain become activated and are prone to perceive danger even in non-threatening situations. These lower parts of our brain are responsible for keeping us alive and are important when facing life-threatening situations. The challenge with children and teens who have been exposed to prolonged periods of stress or danger is that even when they are in a safe environment, this part of the brain is easily triggered into dysregulation and survival. Meanwhile, the higher and more “human-like” parts of our brain, parts of the brain associated with impulse control, reflection, co-regulation, and decision making, are harder to access when the brain is engaged in trauma responses (see DeBellis & Zisk, 2014, for more detailed information).

A trauma cue or reminder is something that reminds a person of a trauma they’ve experienced. Often, trauma cues affect people outside of their conscious awareness. When cued, trauma responses are activated, and we immediately and unconsciously find ways to survive: to feel safe, secure, and soothed. According to The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (2022), reactions to a cue can include a variety of responses such as intense and ongoing emotional upset, depressive symptoms or anxiety, behavioral changes, difficulties with self-regulation, problems relating to others or forming attachments, regression or loss of previously acquired skills, attention and academic difficulties, nightmares, difficulty sleeping and eating, and physical symptoms such as aches and pains. Older children may use drugs or alcohol, behave in risky ways, or engage in unhealthy sexual activity.

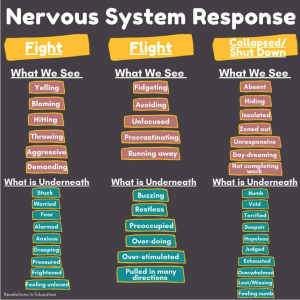

There are several major trauma responses, but a few are directly tied to immediate physiological activation: fight, flight, and freeze.

- Fight: To become aggressive, impulsive, and irritable, often with outbursts to seek or regain power and control. In the classroom this could look like arguing, screaming or yelling, explosive or aggressive behaviors, acting out, or defiance.

- Flight: To leave, distract, or detach oneself, either physically or emotionally. We are hardwired to instinctively escape from dangerous situations (Souers & Hall, 2016). In the classroom this could look like withdrawing or disengaging from work or people, eloping from the classroom or the building, or avoiding. Fear, anxiety, and signs of perfectionism may also accompany this response. When we are unable to escape, we will resort to a fight response.

- Freeze: To become impaired or frozen, unable to think clearly, move, or make a choice when overwhelmed by trauma. In the classroom, a loss of connection to the body or emotions could look like isolation, disassociation, or an inability to make decisions. Incomplete work, unresponsive, zoned out behavior can also be indicators of a freeze response.

The responses we tend to engage in when faced with trauma cues or reminders are highly influenced by which responses have worked for us in the past. Our biological sex can also matter, with females more likely to engage in freeze responses than males (Jones & Monfils, 2016).

PRO TIP

Can you think of a student who demonstrated a flight or fight response? What did that look like in the moment and how did you respond? How might you respond knowing it was trauma induced?

Can you think about a student who demonstrated a freeze response? What did that look like in the moment and how did you respond? How was it different than a flight and fight response?

In children and teens, signs of trauma may manifest as challenging behaviors. It’s crucial to recognize that the impact of events, rather than the nature of the events themselves, defines trauma. When individuals encounter stress, their minds and bodies respond. Those who have experienced trauma may find it challenging to regulate their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors, even in non-threatening environments. Confusingly, reactions to trauma can vary widely among children. Some may exhibit aggression, while others withdraw. Sleep patterns can also differ, with some children struggling to sleep and others sleeping excessively.

There are two broad categories of behaviors in which many children exhibit challenges:

- Externalizing Behaviors – these behaviors can occur when stress or anger is taken out into the environment. This often includes aggression (both physical and verbal), stealing and destroying things in their environment. These behaviors can often be seen when children rely heavily on fight or flight responses to cope with trauma or trauma reminders and are more commonly observed in male than in female children (Liu, 2004).

- Internalizing Behaviors – these behaviors occur when the stress is pulled inside the body, and the person is keeping all their feelings inside. These actions over time may lead to depression, anxiety or other self-harming behaviors. This may include cutting, withdrawing from social settings, wanting to be alone, being irritable, eating or sleeping more and difficulty concentrating. These behaviors are often seen when children rely heavily on freeze responses to trauma and are commonly seen in females (Liu, 2004).

When any of these behaviors occur, it is important to help deter them, but most importantly that we see these behaviors as indicators that a child is needing support other than telling them to stop the behavior. Children can’t “stop” striving to be safe – it’s a biological imperative. Children can begin to rely on new and more prosocial behaviors when they feel safe and when they have supportive relationships that can promote their growth.

PRO TIP

Think about your responses to unwanted behavior. What is the child trying to tell you? The steps to changing a behavior include describing it, identifying an underlying feeling, helping the child get calm or back into a thinking mode, and then co-creating a safer replacement behavior.

Example: A child pulls all the books off a shelf.

Typical Statement: “Don’t do that… You are not listening…”

Acknowledging Statement: “Sometimes it may seem like adults are not listening to your good ideas. What is the best idea you have ever had? Can you name your favorite books?”

Example: A child refuses to try an activity

Typical Statement: “You are not following directions… You are not acting like a ____ grader”

Acknowledging Statement: Taylor, I see it is hard to get started. It seems like the traffic light in your head is yellow or red, telling you that you can’t do this. You are following the signal, but how long do we need to wait for it to turn green? What can we do to help the light turn green?

Example: A child refuses to try an activity

Typical Statement: “You are not following directions… You are not acting like a ____ grader”

Acknowledging Statement: Taylor, I see it is hard to get started. It seems like the traffic light in your head is yellow or red, telling you that you can’t do this. You are following the signal, but how long do we need to wait for it to turn green? What can we do to help the light turn green?

Dr. Chow: Brain Trauma, Neurons safety

When the world is perceived as dangerous, the only way back to regulation is through connection and co-regulation. When we experience threats to our safety, our brain becomes wired to protect us for survival. When we feel safe and regulated, we seek connection, within ourselves and others. As humans we are wired for connection – we need it to survive (Brown, 2012). Unfortunately, we often focus on connecting with others while forgetting that it is equally important for us to connect with ourselves. When our survival mode is activated by the child’s behavior, we see cues of danger, real or perceived, everywhere, and the smallest stressful situation can throw us into reacting from a protective state rather than a connective state. For instance, you might be having the best classroom lesson, and as soon as the child says or does something that you perceive as a threat, you immediately react with anger and/ or anxiety and you start feeling that you must fight, flight, or freeze. We experience this because our internal system is trying to find a balance between the traumatic situation we survived and adapting to the new normal.

PRO TIP

As teachers or school counselors, connection can be assessed by our own sense of wonder. By asking questions for which we don’t know the answers (“I wonder what this child/teen is trying to communicate with this behavior? I wonder what I can learn from this interaction?”); but striving to be present and conscious with a willingness to regard every interaction as an opportunity to learn. This will create an environment that encourages the child or teen to move between the states of connection and protection.

Dr. Gaskill: Attunement and Regulation

REFERENCES

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, Love, parent, and lead. Baker & Taylor.

DeBellis, M. D. & Zisk, A. (2014). The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 23, 185-222. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1056499314000030?via%3Dihub

Desaultes, L. (May 2021). Nervous System Response [online image]. Misunderstanding about discipline. https://revelationsineducation.com/misunderstandings-about-discipline/?v=4096ee8eef7d

Jones, C. E. & Monfils, M. H. (2016). Fight, flight, or freeze? The answer may depend on your sex. Trends in Neurosciences, 39, 51-53.

Liu, J. (2004). Childhood externalizing behavior: theory and implications. Journal of child and adolescent psychiatric nursing: official publication of the Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nurses, Inc, 17, 93–103. https ://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2004.tb00003.x

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (NCTSN, 2022) The National Child Child Traumatic Stress Network. Effects. https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/early-childhood-trauma/effects